The Road to Hell – 1345-1373

The death of Peroz II, the first Babakid Shahanshah, sent Persia on the path to another decade of civil war in a period of internal strife that rivalled only the twelfth century Mazdaki Wars in its prolonged and destructive nature. Much like the conflict that had seen Peroz rise to power in the 1320s, this was pitched a variety of different factions against one another.

The largest rebel faction, and the one that triggered the war, was a traditionalist princely revolt aimed at restoring Zoroastrian Orthodoxy, and receiving the backing the High Priesthood. This Orthodox faction rallied around the claim of the Satrap of Yazd Darius Vali – who had a connection to the fallen Bavandid dynasty as a grandson of Shahanshah Sina through his second daughter Leila. His supporters were scattered around the empire – in Yazd itself, Kerman, Fars, southern Iraq, Syria, Azerbaijan and among the Turkmen. From the start the Valids were met with difficulties. The powerful Koohdashtids of Khorosan and Transoxiania had initially conspired to join Darius’ revolt, but relented in favour of pursuing their own claim to the imperial crown – attacking the Turkmen before they could deploy their forces south to assist the wider Orthodox rebellion.

The second rebellion, with a powerbase in the central Persian Jibal region, did not coaless until the second year of the civil war as these lands were ravaged by the rampaging Babakid and Valid armies. It began as a peasants revolt, but soon received the backing of the local lords who sought to capture this popular energy for their own ends. It centred around the pretender Bakhtiar – who descended from the Alborz mountains south of Mazandaran in the aftermath of Peroz II’s death and claimed to be a lost Bavandid Prince who had spent the past decades in hiding. His messianic arrival electified the masses who saw in him a figure who would end the petty squables of the elite and return Persia to good order, true religion and greatness.

Alongside the three claimants to the imperial throne, major religious unrest broke out on either side of the empire – with Christians rising in Palestine and Manicheans in Khorosan. These revolts would act to paralyse the ability of the Syrian lords to take part in the early exchanges of the civil war while they sent their forces south, and equally limited the Khoodashtids capacity to project their power while they addressed their own religious threat.

In the opening stages of the war the Babakids were the first to take aggressive action. From his core territories around Mosul, Shahanshah Amin struck southwards towards Baghdad, gaining many new recruits from the local Arab Muslim population to place the great city under siege. However, after an unsuccessful attempt to storm the city, Amin was forced to settle into a lengthy siege. To the east, his brother Vahhab had led a second Babakid army, including the feared Mazandarani Mongol contingent, into the Jibal where he had engaged Darius in a number of battles. The dramatic outbreak of Bakhtiar’s revolt in the region then forced him to flee as the lost Prince’s massed swarms overwhelmed the Babakids.

With the Babakids on the backfoot, soldiers loyal to Darius descended from Azerbaijan to capture Tabriz – the largest city that had remained loyal to Amin. With a large population of Armenians and Kurds, Darius’s men massacred many thousands following their victory – viewing these non-Persian groups a Babakid fifth columnists. Following this, after fighting some brief skirmishes against Bakhtiar’s forces, the two Orthodox rebel armies agreed to cooperate against their common foe – directing all their energies against the Babakids and Mosul. Fearing the loss of his capital, Amin broke of his siege of Baghdad to confront the enemy at the battles of Mosul and Babek – scattering them from the field. With the Babakids now on the offensive once more, Amin moved north to subdue Azerbaijan and the Caucuses before returning south in 1348, already three years into the war.

While war raged in the heart of the empire, Palestine was ablaze. Early in the civil war an ageing Christian knight, Kozma, had led a rising of the Christians of the Holy Land against their Zoroastrian overlords. Kozma met with great success, capturing Jerusalem and proclaiming himself Duke. As he called for support from the Greeks, Bulgarians and Kozarians, his Orthodox Christian kin, none would agree to march to war but each provided aid that would allow him to keep the Persian lords of Syria at bay and its independence intact for years. However, in late 1347, not long after the battle of Babek, a Babakid army under the command of the Armenian general Thoros marched into Syria and crushed the rebellious Satraps in a short campaign of great brutality. He moved to uproot many of the existing ruling families of the region and replace them with loyal followers of the Babakids, and their Mazdakite wing of the Zoroastrian Church – turning the regional elites away from their history as a bastion of religious Orthodoxy. Thoros continued his campaign southwards – defeating Kozma and recapturing Jerusalem. By the summer of 1349, all of the western provinces had been safely secured by the Babakids.

In the east, tensions between the declining power of Zoroastrianism and the rising star of Manichaeanism had been growing for the better part of a century by the outbreak of civil war in 1345. Shahab II Koohdashtid had attempted to maintain a balancing act in his increasingly divided realm, yet this would soon be disrupted by the war. In the opening phase of the conflict, Shahab had sent his armies to subdue the Turkmen, who had pledged loyalty to Darius. Under the command of the Manichean general Mashad Dizaid, the Khorosani armies met with tremendous success against their foes. With great prestige, and having little interest in the dynastic struggle in the west, Mashad proclaimed himself the rightful Shah of Khorosan, to the delight of his co-religionists.

As Shahab unleashed a purge of Manicheans within his administration in Khiva who he feared would side with Mashad, and a spare of pogroms against Manichean civilians throughout his realm, Khorosan fell into a bloody civil war. For much of this conflict, the Koohdashtids held the upper hand against the lowborn Mashad, largely shunned by the nobility and regional elites. The decisive engagement came in 1350 at Herat, the hear of the rebellion. Shahab had been besieging the city for over a year, with Mashad and his inner circle trapped inside. However, a large peasant army drawn from the wider region surrounded Shahab’s own army. As Mashad sallied forth from the city, Shahab was trapped in a pincer and was killed on the field of battle. Shortly later Shahab’s brother, Shahrokh, made peace with the Manicheans – giving them control over Herat as the first Persian Manichean state in the faith's long history.

Back in the west, from 1349 Shahanshah Amin set his sights on the lands east of the Zagros. Here, since the twin victories at Mosul and Babek, the brief unity of the two Orthodox factions had fallen away – with Bakhtiar consolidating most of Persian heartland and forcing Darius to withdraw to Baghdad. Amin’s initial attempts to push into these territories proved disastrous. Faced with an implacably hostile local population and a motivated enemy, the Babakid army was almost completely destroyed by Bakhtiar. In Iraq, Amin’s brother Vahhab met with greater success – starving Baghdad into submission in 1350 and capturing Darius – killing him and ending his rebellion. With Iraq secured, Amin made a second attempt to cross the mountains in 1351. He met with some limited success – capturing the great city of Isfahan. Yet, such was the cost of this campaign his forces were far too depleted to push on and finally quash the prince from the mountains.

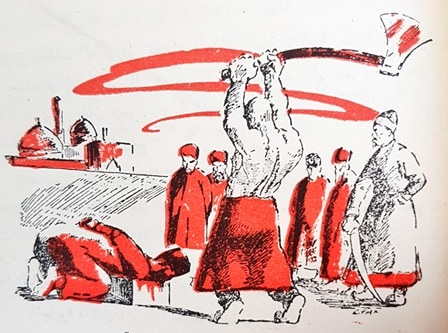

The deadlock was broken by an unexpected emissary who arrived at the court of Shahrokh Koohdashtid in Khiva from the Shahanshah later in 1351. The Khorosanis had been nominally at war with the emperor since 1345, although with their own civil war having only recently concluded their involvement had been extremely minor. The Babakids offered to recognise Shahrokh’s independence from Mosul in exchange for him joining their war effort and attacking Bakhtiar from the east. When Shahrokh agreed, the fate of the war was effectively sealed. Through the next two years the Khorosanis and Babakids made great progress – pursuing Bakhtiar back towards the Alborz mountains from where he had first appears. In 1353, after eight years of war, he was captured near Qom – forced to renounce his claims to imperial lineage, revealing himself as the son of shepards, not kings, and finally lay down his arms. Having hoped for mercy, the pretender was duly flayed until dead by the victorious Babakids and his body displayed publicly in Tehran for all to see.

Having won a second near-decade long civil war in the space of two generations, the Babakids had secured their power once more. Yet the empire had been badly broken by the exhaustions of the conflict and her eastern provinces had definitively slipped from her grasp.

Although victorious in war, nefarious drama never lurked far from Persian royalty. The Shahanshah and his brother Vahhab and worked together closely to defend their father’s legacy during the recent civil war. Nonetheless, the pair despised one another. Beyond the inevitability of brotherly rivalry and jealousies, the pair had competed with one another for the affection of their cousin Aryana. Shortly after his ascension to the throne, Amin had ended this contest by taking Aryana as his wife. Yet Vahhab continued to care deeply for her, and was despondent at her poor treatment at the hands of his brother – who regularly beat her severely, often in public. Following one of his rages against his wife in 1355, Amin killed Aryana with his bare hands. Filled with rage, Vahhab confronted his brother in the gardens of the imperial Babakid palace in Mosul and, as a scuffle ensued, stabbed his brother to death. Having committed a fratricidal act of regicide, Vahhab had to move quickly to seize power lest he face the consequences of his bloody actions – installing his nephew Peroz III on the throne and establishing himself as regent. With the support of the Babakid military, loyal following his service in the civil war, and with most opponents of the crown still yet to recover from their defeats in war, Vahhab was secure.

With imperial power having fallen into his hands, Vahhab moved early in his regency to make use of it for his own ends. In 1357 his led his armies northwards against the Kozarians in a struggle for control over eastern Armenia. The Persian army captured Yerevan and then, in their first major engagement with the Kozarians, secured an even more valuable prize – the Kozarian crown prince Vachagan. Despite having more than enough resources to continue to fight, the Caucasians chose to cut an early truce in order to ensure the safe return of their prince – surrendering the army over to Mosul’s authority. Hailed for his rapid victory by the military, Vahhab proceeded to claim the title Shah of Armenia for himself.

Persian authority on her western frontier was seriously threatened during the late 1360s by an intimidating Neo-Byzantine revolt that was sparked by the arrival of a descendant of the last reigning Basileus in Cilicia with a band of soldiers. The Byzantine rebels found mass support among the native Greek and Armenian peoples of Cilicia and Eastern Anatolia – and significant aid from the neighbouring Greek states and the Kozarians. The rebellion proved difficult to contain, with the Greeks and Armenians answering the call of the Roman banner of old in their tens of thousands – overwhelming the armies of the Syrian lords, and ransacking their lands and forcing them to call on Mosul for aid. Even after the arrival of imperial aid, it would take more than three bloody years of fighting for order to be restored through all of Cilicia and the rebellion to finally be quashed.

The Persian nobility of Syria had been utterly devastated by the rebellion – with dozens of lords and Satraps slain. Furthermore, the experiences of the conflict had brought attention to the weakness of the western frontier – which had been unable to defend itself without the aid of Mosul. Vahhab therefore sought to consolidate the western territories into the Syrian Shahdom that stretched from Cilicia in the north to Palestine in the south, under the rule of Mashad Ayeshahid in Aleppo. Mashad was a closely ally of Vahhab, and like him a strong believer in the Mazdakite reformation of the Zoroastrian Church.

While in Iran, Persia’s elites focussed on their internal struggles and its regent Vahhab grew ever more comfortable in his power, a figure was rising in the east that would soon make the very mountains of the earth shake. Timur. The Iron Khan.

Last edited:

- 1