Rise of the Iron Khan 1373-1381

Timur was born in 1341 into a humble Turco-Mongol Manichean background, with a Khiva Mongol father and Karluk mother in what was still the easternmost frontier of the Persian empire in the Khoodashtid Khorosan Shahdom. As a young child Timur and his family were sent into flight after the armies of Shahab II of Khorosan destroyed their native village not far from Bukkhara and sought to slaughter all the Manicheans they could find – leaving the young Timur with a lifelong hatred for Zoroastrian Orthodoxy. Arriving near Afghan-ruled Samarqand, there, after failing to find any opportunity among a swathe of fellow refugees, Timur’s father took to banditry – abandoning Timur and his mother. From a young age, Timur therefore took to thieving - – whether from the pockets of the rich in Samarqand, the caravans that criss-crossed the Silk Road or the cattle and horse herds in the countryside – to sustain himself. At the age of fourteen he was badly injured, leaving him lame in his right arm. Shortly later, he fled the region entirely after a blood feud with a clan of Karluks escalated into a cycle of violence with which he could not compete.

Timur would travel west, to the Persian province of Mazandaran, to enter into the service of a Mongol chieftan named Konchek. The Mazandarani Mongols regularly sought to refresh their soldier corps with new recruits from the east, and happily took on the young bandit and turned him into a warrior. Timur spent the next decade and a half of his life in Konchek’s service. Blooded in battle against the Kozars in 1357, still just sixteen, he soon proved himself ferocious on the field and a startling genius in command. By his early twenties he was already Konchek’s most trusted general, and aided him in establishing himself as the ruler of the entire Alborz range – from Gorgon in the east to Ardahan in the west and pressurising Vahhab into recognising him as the Satrap of Mazandaran.

Timur’s call to greatness would come from upheavals in his homeland in the east. Few parts of the Iranian world were as unstable as Central Asia in the second half of the fourteenth century – a remarkable feet considering the troubles afflicted the entire region. The region around Samarqand and the Fergana Valley was already overpopulated following an influx of Manicheans and other refugees from Khorosan during the Persian civil war of the late 1340s. However, two decades later its fragile stability would start to crack following the Panjabi conquest of Kabul from the Afghans – which triggered a migration of Pashtuns from their traditional homelands northwards.

This triggered conflict between the Manichean Karluk natives and the mostly Zoroastrian Pashtun incomers. With the Manichean Yamag Imonbek openly supporting the re-establishment of a Karluk Khanate, the Turkic rebels slaughtered thousands of Pashtun incomers but were ultimately overcome by the superior organisation of the Afghan Shah. Victorious, the Afghans showed now mercy – ransacking Samarqand, destroying its great Manichean temples and burning the Yamag at the stake in 1371.

News of these events drove Timur into a blind rage and he asked permission from his liege to go east to avenge his co-religionists. Konchek, a Khurmatza with little sympathy for the Orthodox Zoroastrians, granted this request and allowed Timur to take several hundred of his veteran warriors with him as he rode east.

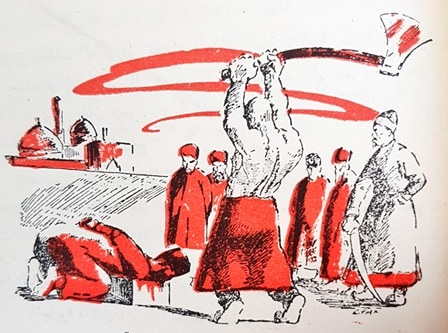

Arriving in Transoxiania with his modest force, Timur defeated an Afghan army five times his number in battle and stormed into Samarqand. He then unleashed a campaign of incredible brutality the entire Pashtun population of the region around the city – killing tens of thousands, men, women and children alike. With the area secure, in 1373 the new Yamag in Samarqand anointed the lowborn son of a bandit as Khan and named him the leader of the Army of Light – the defender of the Manichean faithful. This unity between faith and military power would make the Timurid hordes a magnet for Manichean warriors, not only from the Persianate lands of Transoxiania and Khorosan – but also the vicious Steppe to the north.

The nature of Manichean philosophy played a significant role in shaping both Timur and his horde. A contradictory faith that could be both incredibly gentle and stark. Its priestly cast believed in absolute non-violence that extended to a vegetarian diet so strict that they were themselves forbidden from preparing food themselves lest they arm the life-force of the plants. Yet, much like Zoroastrianism, it was a dualistic religion – with an even sharper focus on the black and white divide between good and evil, light and dark. For the Timurids, their enemies were undoubtedly of pure darkness, for whom the only salvation from complete submission to Mani’s godly truth.

Samarqand was only the beginning as over the next four years the Iron Khan unleashed a blistering campaign to unify Khorosan and Transoxiania under his banner. He destroyed the pathetic remnants of the Koohdashtid Shahdom – seizing Khiva. He then made war against the Persian-aligned Turkmen – forcing them to switch allegiance to him and warding off the timid Iranians from daring to intervene to stop him. In the east, he pursued his bitter campaign against the Afghans by purging them from the Fergana Valley and committed similar genocidal massacres as he had around Samarqand – wiping any trace of the Pashtuns from Karluk soil. To the south, Timur capture Kabul from Punjabis and allowed his men to wantonly sack the city for an entire month – killing and enslaving the entire population of what was once one of the great cities of the east, completely his revenge for the outrages against Samarqand. Meanwhile, the Dizaids, despite their shared faith, were initially circumspect about Timur and his barbarity, but quietly agreed to join him as a vassal after he sent twenty thousand riders to camp outside Herat.

While a new threat arose in the east, important events were taking place in the heart of imperial Persia. After a long regency, Shahanshah Peroz III had begun to chafe under the supervision of his uncle Vahhab as he entered his maturity in the early 1370s. Having come to power after the murder of his own brother, Vahhab chose to take to the knife once more in order to defend his position – having his nephew murdered in cold blood in 1374 and place the fallen emperor’s two year old daughter Donya on the throne. Vahhab underestimated the level of scorn and revulsion such brutality would provoke – sending Persia on the path to its third major civil war in a single lifetime, with lines being drawn in the land along familiar religiously-based lines.

The fighting was sparked by an unlikely coup, as the Armenian general Thoros – who had fought alongside Vahhab in the previous civil war and led the subjugation of Syria – kidnapped Donya in Mosul in 1375 and defected to the Babakids’ rivals, riding to Baghdad and installing Donya in New Ctesiphon under stewardship of a cabal of Orthodox Zoroastrians. Furious. Vahhab mobilised his armies and marched to war to reclaim the guardianship of his great niece and with her the legitimacy to rule Persia.

The conflict began particularly poorly for Vahhab who was badly defeated in his campaign in souther Iraq aimed at capturing Baghdad and reclaiming custody of Donya. From there, the situation would go from bad to worse as the Orthodox armies counterattacked towards Tabriz, with the aim of linking their armies in the Jibal with those in Azerbaijan. After capturing the city, the bulk of the Orthodox forces moved on Assyria, where Vahhab desperately battled for his life alongside allied forces drawn from Armenia and Syria – leaving the Mazandaranis, who had once again backed the Babakids, isolated to the east.

As had been the case in previous Persian civil wars in the past century, this conflict carried with it many acts of religious and ethnic violence. The most consequential of which occurred after the fall of the Mazandarani city of Ardabil on the south western short of the Caspian to the Orthodox Zoroastrians in 1377. Victorious after a long siege, the Orthodox forces unleashed their frustrations against the native population of Khurmatza heretics – killing them in their scores. The worst violence was reserved for the Mazandarani Mongol minority who were targeted for systematic slaughter as the Orthodox Zoroastrians sought to leave none alive. These killings saw one of the sons of Konchek, the Satrap of Mazandaran, and two of his daughters beheaded by the conquerors. With the rest of his territories isolated and his people under existential threat, Konchek sent an envoy to his old commander and friend in Samarqand pleading for aid and protection. Timur responded by occupying Mazandaran, accepting the vassalage of his former liege, and daring the Persians to challenge him.

The Timurids were not alone in taking advantage of Persian infighting. To the south east, the Omani Christians of the Hamrid Sultanate had grown wealthy through piracy and trade in the Indian Ocean over the preceding century – establishing one of the most successful Arab states since the Islamic Götterdämmerung of the High Middle Ages. With their powerful neighbour to the north distracted, in 1376 they crossed the Straits of Hormuz – capturing the important port of Bandar Abbas and the wider province of Kerman before turning east to push the Indians out of Baluchistan. In what was a lightly populated and underexploited region, the Omanis would establish a string of colonies along the coastline of their new conquests.

Back to the west, the Persian civil war was reaching its conclusion by the end of the decade. In 1379 Mosul fell and Vahhab was captured. Placed in a cage, the regent was taken back to Baghdad where the Moabadan-Moabad Parviz led a public trial of the man who had dominated the empire for so many years for the regicide of two emperors and the proliferation of heresy. Found guilty, Vahhab was then quartered – with parts of his mutilated corpse being sent across the empire. Shortly after Vahhab’s execution, the High Priest’s nephew, Ardahan of the Jibal Satrapy, was married to Empress Donya, still only a child. With this marriage, Ardahan had himself crowned as the new Shahanshah, in close alliance with his uncle.

With Mosul lost and Vahhab slain, and the Babakid faction falling away, the civil war was not yet over. In the Levant, the Ayeshahids had shifted from supporting Vahhab’s war effort to seeking independence from the emerging Orthodox-dominated Persian state. Following a failed effort to push westward towards Aleppo, Baghdad chose to accept this separation – agreeing a truce in 1380 that allowed the Ayeshahids to establish an independent Syrian Shahdom. Within a year of this peace, the Ayeshahids had provoked a schism in the Zoroastrian Church – establishing a Mazdaki Zoroastrian High Priesthood in Aleppo that attracted widespread support not only in their own lands in Syria but across the border in the former Babakid heartlands of Armenia and Assyria.

Emerging from civil war diminished and as divided as ever, the long shadow of Timur loomed over Persia.

- 2

- 1