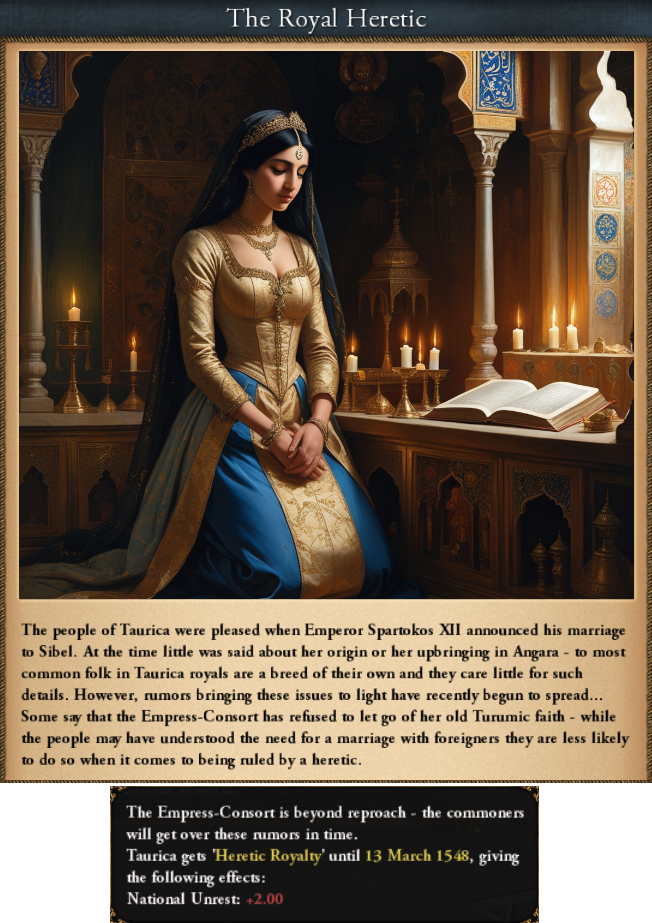

These events also had an impact on the situation in the Grand Principality of Tauric and the Empire at large, though their effects were initially mostly informational and ideological. In Satyria and other parts of the Empire, one increasingly encountered people sympathetic to the ideas of the Reformation. Over time, this movement began to evolve into a new ideological-religious current known as Onomism. These new teachings started to gain followers among the urban populations of the Empire.

Could the rebellions cause a crack-down on religious minorities?...The Church in the Tauric Empire had so far maintained unity, but was becoming increasingly vigilant in the face of possible changes.