The First Geographical Discoveries – Late 15th Century AD

By the late 15th century, Western Europe was grappling with increasing difficulties in accessing luxury goods from distant Asia, such as spices, silk, and porcelain. For centuries, these goods had reached the West through an extensive network of trade routes, but this situation began to change drastically.

One of the key reasons for this crisis was the collapse of the great Mongol khanates, which in the 14th and 15th centuries controlled vast territories of Eurasia and guaranteed the safety of trade routes. In the first half of the 15th century, the Yuan dynasty, the Blue Horde, and the Purple Horde disintegrated, leaving behind political chaos and civil wars. As a result, the Silk Road routes became dangerous, and trade between the East and the West was severely restricted.

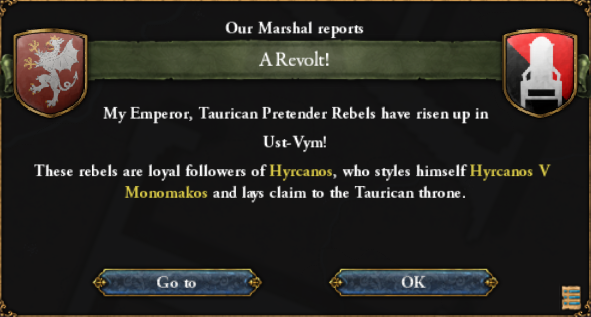

An additional problem for the Western European kingdoms was their centuries-long dependence on intermediaries controlling trade in the Middle East and North Africa. For centuries, goods from China and India were transported through lands belonging to the Tauric Empire, the eastern Coptic kingdoms, and Mainkeist Persian states. Each of these states imposed high tariffs and set their own trade conditions, making these goods increasingly expensive and harder to access for European merchants.

This situation led to a chronic imbalance in trade, with the greatest profits going to the intermediary states. Western European kingdoms, such as Adberia, Memoriana, and Alamea, increasingly realized that their wealth in gold and silver was flowing eastward, leaving them economically dependent on Middle Eastern intermediaries. Tauric and Coptic ports, such as Alexandria and Smyrna, became key points controlling access to Asian goods, further frustrating European monarchs.

Faced with these challenges, Western European rulers began searching for alternative routes to access the riches of Asia. By the late 15th century, the first expeditions to explore oceanic trade routes were organized, marking the beginning of the great era of geographical discoveries. Expeditions launched by Adberia and Memoriana aimed to bypass Middle Eastern intermediaries and find new, direct connections to India and China. This drive to break the trade monopoly became one of the main forces behind Europe's maritime expansion at the end of the 15th century.

However, knowledge of the riches of these exotic lands was not new. For centuries, tales of the fabulous wealth of the East had circulated, but it was only with the dissemination of the memoirs of Satyros Satyrion on Western European courts that this knowledge gained new significance. Satyrion, an 11th-century Tauric traveler, undertook an extraordinary journey through India, China, and Africa. His stories of great cities, golden temples, and immense wealth captured the imagination of many.

Satyrion's memoirs, written in the Tauric language and translated and disseminated during the Renaissance in the mid-15th century, became one of the works that inspired sailors and explorers. In the early Renaissance, as the idea of discovering new worlds grew increasingly popular, his described travels became proof of the existence of distant lands full of riches.

In particular, his accounts of expeditions to India and China convinced many that these lands could be reached by sea. It was thanks to works like Satyrion's memoirs that Western European rulers began making decisions to organize the first great maritime expeditions. The desire to find new trade routes and reach the legendary lands of India and China was one of the main reasons why the Adberians were the first to challenge the unknown waters of the ocean and set out in search of new lands.

Portrait of Satyros Satyrion, Renaissance, created by Aniochos Angelos beginning of the 16th century - (ChatGP)

1 - Expedition of discovery of the kingdom of Adberia (1498–1500)

At the end of the 15th century, the Kingdom of Adberia, a powerful Punic state extending its rule over the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa, became one of the pioneers of Atlantic exploratory expeditions. For centuries, the Adberians, as descendants of the great Carthaginian sailors, had been a seafaring people.

The rulers of this kingdom invested in the development of their fleet and the exploration of new trade routes, which allowed them to take control of Madeira and the Canary Islands. When, by the end of the 15th century, the possibility of discovering new lands across the Atlantic was increasingly considered, a man appeared at the court of King Hadron II who intended to undertake this risky mission—an adventurer, explorer, and sailor named Hanno Columbi.

Hanno Columbi, an ambitious and determined explorer, managed to convince Hadron II that it was worth financing an expedition westward in search of new lands and riches. Adberia, whose economy struggled with limited access to Eastern goods, needed alternative trade routes.

Columbi, drawing inspiration from earlier expeditions and legends of distant lands, promised the king gold, spices, and new opportunities for expansion. Thanks to his experience at sea and knowledge of ocean currents, he became the ideal candidate to lead an expedition aimed at finding a route to India or discovering unknown lands.

Adberia had a rich maritime tradition, and its people had explored the coasts of Africa and the western Atlantic for generations. Among the Punic legends, one of the most inspiring examples was Hanno the Navigator, who centuries earlier had led a fleet through the Strait of Gibraltar and explored the African coastline.

Accounts of his journey suggest that he may have reached as far as Gabon or Cameroon, though other interpretations point to Guinea or Sierra Leone. Along the way, he took guides and interpreters, allowing him to communicate effectively with local populations. Hanno's expedition was proof that the Carthaginians were capable of long voyages and could serve as inspiration for later Adberian explorers.

The tales of ancient sailors, along with the growing competition among European maritime powers, prompted Hadron II to give Columbi a chance. The Kingdom of Adberia sought to find its own path to the riches of the East and free itself from the control of Persian and Tauric intermediaries. Thus began a new era of great Adberian oceanic expeditions, in which Hanno Columbi was to play a key role, setting sail into the unknown waters of the Atlantic in search of new worlds.

The expedition of Hanno Columbi was one of the most ambitious voyages in the history of the Kingdom of Adberia. It consisted of five ships—four nimble caravels and one powerful galleon, Carthago, which served as the flagship.

Onboard the fleet were around 300 people, including experienced sailors, armed soldiers, merchants seeking new trade opportunities, and scribes tasked with documenting all discoveries. The fleet's mission was not only to find new lands but also to explore trade possibilities and establish contact with unknown peoples.

On June 1, 1498 AD, the fleet was ceremoniously bid farewell at the port of Fara, from where it was to embark on its historic journey. For the last time, the crews gazed at the familiar shores of Adberia before raising the anchors and setting the sails.

The first destination of the voyage was the Canary Islands, long under Adberian control, where they planned to replenish supplies of water and food and repair any damage to the ships after the initial leg of the journey. The trip to the archipelago went relatively smoothly—favorable winds and the expertise of Adberian navigators allowed them to reach their destination quickly.

After a brief stop, the fleet set a course along the African coast, heading south. Columbi, inspired by the ancient Carthaginian sailors, planned to follow known coastlines, stopping at strategic points such as Tidra and Ngor, where they hoped to trade with local tribes.

Although sailing along the coast was relatively safe, the sailors began to feel uneasy—ahead of them stretched the unknown expanse of the ocean, and among the crew, tales of sea monsters and terrible storms began to circulate.

Upon reaching Ngor, an island off the African coast, Columbi decided to set sail westward toward the Cape Verde Islands, the last known stop before venturing into the open waters of the Atlantic. After several days of sailing, Hanno Columbi's fleet reached the archipelago.

These islands, located off the western coast of Africa, had been visited before by Adberian sailors but remained largely unexplored and sparsely inhabited. Columbi ordered a several-day stop to replenish supplies of fresh water, dried food, and wood. The crews went ashore, where they could rest after the journey so far.

Despite the temporary respite, tension began to grow among the sailors. They knew that ahead of them lay an unknown ocean, with no maps or established routes. Voices of doubt began to emerge, and some openly suggested turning back.

Columbi, however, remained resolute—after a few days of preparation, when the Carthago and the other ships were fully ready to continue the journey, he gave the order to set sail. On July 9, 1498 AD, the fleet left the Cape Verde Islands and headed west, into the mysterious waters of the Atlantic, toward unknown lands.

On July 12, 1498, the fleet of Hano Columbi sailed westward into uncharted waters when suddenly the sky darkened with storm clouds, and the ocean churned violently in an instant. A fierce storm, with the force of a hurricane, struck the flotilla.

The raging waves scattered the ships, and the wind tore at the sails, snapping masts and shredding rigging. The crews fought desperately to maintain control of their vessels, but one of the caravels, the Lion of Carthage, was not so fortunate.

The ship was damaged and began to sink. Sailors leaped into the water, trying to save their lives, while the rest of the fleet could only watch helplessly. Eventually, the survivors were rescued and taken aboard the remaining ships, but the disaster dealt a heavy blow to the expedition's morale.

Exhausted and battered, the fleet was forced to return to the Cape Verde Islands, where it arrived on August 1, 1498. For the following weeks, the crew focused on repairing the ships, replenishing supplies, and tending to the wounded.

Columbi feared that the growing discontent among the sailors might lead to mutiny—many saw the storm as a bad omen and wanted to abandon the voyage. To prevent this, the commander personally addressed the crews, convincing them that great discoveries required sacrifices and that future riches would reward their hardships.

On September 15, 1498, the fleet set sail westward once more, this time better prepared for the dangers of the ocean. Over the following weeks, the sailors endured unbearable heat, tropical storms, and the first signs of disease. The Atlantic waters seemed endless, and the horizon remained empty, fueling fear and doubt among the crew.

After many weeks of exhausting navigation through uncharted Atlantic waters, on October 13, 1498, the crew of Hano Columbi's fleet spotted land on the horizon for the first time. Joy and relief swept through the sailors, who cheered and thanked the gods for their salvation. After days of drifting in uncertainty, they had finally reached a new and unexplored land.

The fleet headed toward the coast, and after a few hours of sailing, the explorers landed near Rio Grande on the eastern coast of Brazil. Filled with triumph, Columbi named the newly discovered land New Carthage, in honor of his ancestors and the maritime power Carthage had once been.

As the explorers set foot on the new land, they were greeted by unfamiliar landscapes—dense forests, expansive coastlines, and extraordinary species of animals that filled them with wonder. Scribes diligently recorded their observations, describing colorful birds, towering trees, and vast rivers that cut through the land.

The waters teemed with fish, and the climate was warm and favorable for settlement. Columbi knew this was only the beginning of great discoveries and decided to continue the journey northward to explore more of this unknown territory. After a few days of rest, during which the ships were repaired and fresh water was replenished, the fleet set sail along the coast once more.

On December 10, 1498, the fleet reached a small island off the coast, which they named Ilha Machadinho. It was an extraordinary place—lush vegetation, towering trees, and exotic animals captivated the travelers.

The sailors were amazed by the richness of the natural world, and the scribes strove to document every new plant and creature they encountered. Many of them had never seen such diversity of flora and fauna, which evoked both excitement and unease. Columbi ordered the exploration of the island, sending small groups on reconnaissance missions to determine if the location was suitable for establishing a camp.

During the exploration of the island, the first contact with the indigenous people occurred. Initially, the natives were wary and kept their distance, observing the newcomers from the dense jungle. The sailors, not wanting to frighten them, remained cautious and avoided sudden movements.

Columbi, understanding the importance of first contact, decided to employ a proven tactic—he sent a group of envoys ashore with small gifts, such as colorful beads, small mirrors, and metal tools. This gesture was meant to demonstrate peaceful intentions and pique the curiosity of the natives.

After a few hours, the natives approached closer and began to observe the strangers. They were tall, well-built, and nearly naked, adorned with feathers and body paint. Their gazes were cautious but also curious.

Slowly, the first exchange began—the indigenous people brought exotic fruits, animal skins, and strange-looking roots that they claimed had medicinal properties. In return, they received metal knives and axes, which immediately captivated them as these were highly valuable items. Columbi saw this as a good sign—a first step toward establishing positive relations with the natives.

After a few days on Ilha Machadinho, Columbi decided it was time to continue the journey further north. Although the expedition had not yet found the dreamed-of riches, the discoveries made in the new land offered hope for further success. The fleet set sail again, leaving behind the island that had become the first site of Adberian contact.

The journey had already lasted a year, and fatigue and frustration were growing among the sailors. The lack of fresh food, the heat, and tropical diseases caused morale to decline with each passing day. Many began whispering about returning home, claiming that further travel was pointless.

The galleon Carthage and the three remaining caravels sailed slower, and some officers began openly expressing their discontent. At one point, several sailors, led by an experienced helmsman named Barcas, began inciting the rest of the crew to mutiny. They argued that Columbi was leading them to certain death and that it was time to return to Adberia.

Columbi, though aware of the critical situation, had no intention of giving up. He gathered the entire crew on the deck of the Carthage and addressed them. He reminded them of the greatness of the expedition and the honor that awaited them upon their return. He promised that only one task remained—to continue northward—after which they would begin their journey home.

To ease the tension, he ordered the remaining supplies to be distributed fairly, giving everyone extra rations. The mutiny was quelled, though many sailors remained doubtful. They had no choice but to trust Columbi and sail on.

On January 1, 1499, the fleet reached the islands of Trinidad and Tobago. At first, the land seemed paradisiacal—lush vegetation, wide beaches, and fresh water offered hope for rest and resupply.

Columbi sent a group ashore to explore the area and search for food. Unfortunately, this time the natives were not as friendly as those on Ilha Machadinho. When the sailors ventured inland, they were suddenly attacked by a group of warriors armed with wooden clubs, spears, and bows.

A short but brutal skirmish broke out. The Adberians, despite having firearms, were caught off guard and unprepared. Several sailors were killed by club blows and arrows before they managed to repel the attackers and retreat to the ships.

Columbi, seeing that further fighting would be too risky, ordered the fleet to sail on and search for another landing site. Although the clash ended in retreat, it left the crew deeply unsettled—was the New World a place of great riches or deadly dangers?

On April 25, 1499, Hano Columbi's fleet reached a small tropical island that would become their final stop before returning home. Barbados, as the locals called it, was a gift of fate for the exhausted travelers.

Columbi, seeing this place as an opportunity to regain strength, renamed it Phoenix Island, symbolizing rebirth after the hardships of the voyage. The crew's morale, which had been on the verge of collapse for months, began to improve. The sailors could finally rest, heal their wounds, and replenish their supplies of fresh water and food.

During their stay on the island, the crew prepared the ships for the long journey home. Scribes made final notes, mapping the newly discovered lands, while traders sorted the acquired goods. Among the spoils were exotic skins, rare types of wood, seeds of unknown plants, and small native ornaments.

Although no gold or silver was found, the knowledge of the new lands and their resources was equally valuable. After three weeks of rest, Columbi ordered preparations for the journey to the Canary Islands, from where they would return to Adberia.

At the end of May 1499, the fleet set sail from the shores of Phoenix Island, heading east. Initially, the conditions were favorable, but by June they encountered a powerful storm. For several days, gales and massive waves battered the ships, separating the vessels and destroying rigging.

The ship Hannibal suffered particularly severe damage to its hull and masts. Despite desperate attempts to save the vessel, it became clear that the ship was no longer seaworthy. The captain of the Hannibal, with no other choice, made the difficult decision to return to Phoenix Island with his crew, hoping for future rescue.

The three surviving ships—the Carthage and two caravels—continued their journey eastward. The sailors, though exhausted, had one goal: to return home and bring news of the New World. After long weeks of sailing, in mid-September 1499, they reached the Canary Islands, where they could finally rest after the grueling Atlantic crossing. There, the ships were repaired, and supplies were replenished for the final leg of the journey to Adberia.

At the end of November1499, after more than a year and a half at sea, the surviving portion of the fleet returned to Adberia. The port of Faro welcomed them as heroes—though battered and diminished, they were the first Adberians to cross the Atlantic and return with tales of new lands.

Columbi personally reported to King Hadron II about the discoveries, presenting the collected maps and treasures. Although the expedition had lost two ships and many lives, its significance for Adberia's future was immense. The New World awaited further exploration, and the story of Hano Columbi was destined to become a legend.

Portrait of Hano Columbi created by an unknown Adberian painter, early 16th century – (ChatGP)

The First Geographical Discoveries – Early 16th Century AD

The success of Hano Columbi's expedition in the late 15th century was a groundbreaking event that changed the course of history. For the first time, a fleet from Europe crossed the Atlantic and returned with information about new lands. In Europe, it was mistakenly believed that Columbi had reached the eastern shores of the fabled lands of Asia and the kingdom of Cathay. The knowledge that he had reached an unknown continent only spread much later. News of this great discovery quickly spread across European courts, sparking admiration but also envy.

Monarchs realized that beyond the ocean lay riches previously only heard of in legends. Among the nations most keenly following the reports from Adberia was the neighboring Kingdom of Memoriana, which also ruled part of the Iberian Peninsula.

The Kingdom of Memoriana, though long a rival of Adberia, was not lagging behind in maritime exploration. As early as the mid-15th century, its sailors had discovered and colonized the Azores archipelago. Memorian rulers had long dreamed of finding new routes to Asia, but Columbi's success convinced them that the westward path might indeed lead to wealthy lands.

At the royal court in Gijon, the capital of Memoriana, intense preparations for their own expeditions began. The Memoriana monarch, Audoin III, declared that the kingdom could not afford to fall behind and that Memoriana would also set out westward in search of a route to Asia and India. The construction of new ships commenced. Spies analyzed and reported on Columbi's findings, attempting to chart the best route across the Atlantic.

Preparations for Memoriana's first expedition began in 1501. King Audoin III, eager to rival neighboring Adberia, announced that Memoriana would also embark on exploratory expeditions to the west in search of a way to Asia. The Crown allocated vast financial resources to build and equip the fleet, securing support from influential merchants and nobles who hoped for future wealth.

From the arsenals and shipyards of coastal cities like Porto and Vigo, four caravels and one galleon were selected, adapted for long ocean voyages. The ships were loaded with food, water, tools, and goods for trade with indigenous peoples, such as metal blades, mirrors, beads, and cloth.

One of the most critical aspects of the preparations was assembling a suitable crew. The fleet was to carry around 350 people, including experienced sailors, cartographers, scribes, and soldiers to guard the expedition against potential threats. Translators and traders were also recruited to establish contact with the natives. However, the greatest challenge was finding the right commander—a man of great courage, sailing experience, and charisma, capable of controlling the crew during a long, grueling expedition.

After lengthy deliberations, the choice fell on Sebastian Brennin, an experienced captain who had previously sailed to the Azores and along the western coasts of Africa. His knowledge of the oceans and ability to handle difficulties made him the ideal candidate.

After months of preparation, early on the morning of March 3, 1502, the fleet departed from the port of Porto, with crowds of residents bidding farewell to the adventurers setting out into the unknown. Excitement filled the air, but so did anxiety—no one knew what awaited them on the other side of the ocean.

The sailors hoped for riches and glory but also feared storms, hunger, and unknown dangers. The great Memoriana expedition, which would forever change the history of the kingdom, had begun.

1 - The Exploratory Expedition of the Kingdom of Memoriana (1500 - 1504)

The first weeks of the voyage were calm—the fleet headed southwest toward the Azores archipelago, a crucial supply point for Memoria. The sailors were hopeful, and Captain Sebastian Brennin worked to maintain crew morale by distributing rations and organizing daily tasks. However, by the end of March 1502, when the ships were far from European shores, a powerful storm suddenly erupted. The tempest lasted two nights and a day, tossing the ships on the waves and forcing the sailors into a desperate struggle to stay on course.

The caravel Merope suffered the most, separated from the rest of the fleet and sinking overnight with most of its crew. Rescue attempts were impossible—darkness, high waves, and strong winds made any action futile. By morning, the storm had subsided, but the fleet was weakened, and many sailors on the remaining ships were injured. Brennin ordered the voyage to continue toward the Azores, knowing that only there could repairs be made and supplies replenished. The atmosphere on board grew grim—the sailors mourned their lost comrades, and fear of another storm loomed.

After over a month of difficult sailing, on May 10, 1502, the four surviving ships finally reached the Azores. The sight of land brought immense relief to the exhausted crew. The fleet anchored at Terceira Island, where repairs to damaged masts and hulls began. The crew replenished their supplies of water, fresh fruit, and meat, and recruited new sailors to replace those lost in the storm. Brennin convened a meeting of officers and announced that the expedition must continue—the New World still awaited.

On June 12, 1502, after leaving the Azores, Sebastian Brennin's fleet set sail westward into the unknown waters of the Atlantic. Initially, conditions were favorable—trade winds propelled the ships forward, and the weather was fair. The sailors, though anxious, had fresh supplies of water and food, and the thought of new lands gave them courage. However, with each passing week, tensions on board grew. Food began to spoil, the relentless heat weakened the crew, and skin diseases and dehydration took their toll.

In the second month of the voyage, the fleet encountered powerful storms that tossed the ships like toys on the raging ocean for several days. Many sailors were injured, and several fell overboard and drowned. The water in the barrels began to rot, and dry provisions dwindled daily. Disputes broke out among the crew, and the greatest skeptics began to question the purpose of the expedition.

Some began to say they were doomed, that they would never see land again. By mid-August, the situation became dire—hunger and thirst drove people to madness. An open mutiny broke out on the Aurora Magna. Several sailors, armed with knives and hooks, demanded a return home. They claimed Brennin was leading them to certain death and that the only sensible option was an immediate retreat.

The captain, though exhausted himself, knew that losing control of the crew would mean the expedition's failure. With the help of loyal officers, he suppressed the rebellion—the mutiny leaders were shackled, and the rest were promised that land was near. Brennin swore that if they did not see land within three weeks, he would agree to turn back.

Days passed, and the crew's morale teetered on the edge. The bodies of weakened sailors were covered in sores, and many lost consciousness from exhaustion. Rats became a new food source, and some desperate men drank seawater, hastening their deaths. The wind weakened, meaning longer delays on the open ocean, and the sea's silence drove people to madness. Everyone waited for a miracle.

Then, on September 14, 1502, a cry from the crow's nest pierced the air: "Land on the horizon!" The exhausted crew sprang to their feet, staring at the distant dark line against the blue sky. Brennin, hardly believing his eyes, ordered a course change toward the land. After three months of torment, the Memorians had finally reached an unknown land. As the ships approached the shore, the explorers saw forested islands surrounded by azure waters. It was something entirely different from the coast described by the Adberians. Brennin and his men set foot on the islands they named Barbuda and Antigua—a new treasure no one had discovered before.

After long weeks of grueling passage across the Atlantic, the crew of Sebastian Brennin's fleet could finally rest on the newly discovered islands. Barbuda and Antigua became their sanctuary, where they repaired damaged ships, replenished water and food supplies, and rebuilt the morale of the exhausted sailors.

Over the following weeks, after a brief rest, the fleet sailed further west, exploring new, unknown lands. The travelers discovered and described the islands of Puerto Rico, Haiti, and the Caymans, distinguished by lush vegetation, a warm climate, and the presence of indigenous inhabitants.

During the exploration of Haiti, the crew made contact with the natives, who initially regarded the newcomers with caution. However, the Memorians, learning from earlier expeditions, avoided confrontation and sought to trade peacefully. The natives offered exotic fruits, skins, and handmade tools in exchange for European items such as knives, beads, and fabrics. Though tense, these relations did not escalate into open conflict, allowing the sailors to continue their exploration of the region.

During one of the subsequent storms, the fleet lost another ship—the caravel Argento. Powerful waves and violent winds smashed the vessel against rocks, sinking it before the eyes of the rest of the crew. Some sailors managed to survive, swimming to the shores of Haiti. However, the ship was lost, and some survivors were too weakened to continue the journey. Brennin, unwilling to leave them alone in the wilderness, decided to establish a small fort on the island as a refuge for those who could not return. This became Memoria's first European outpost in the New World.

As the beginning of 1503 approached, Brennin decided it was time to return home. The crew was exhausted, and supplies were dwindling. On March 8, 1503 AD, after careful preparations, the last three surviving ships left Haiti and set sail eastward, attempting to find the fastest route back. Brennin, instead of retracing their path through the mid-Atlantic, chose to sail northeast, hoping that winds and ocean currents would help them arc back to the Azores.

Sailing northeast, Sebastian Brennin's fleet battled unfavorable weather conditions. Ocean currents slowed their progress. In these harsh conditions, the crew lost track of days, unsure if they would reach any land or perish on the endless ocean. After weeks of uncertainty, in June 1503 AD, land finally appeared on the horizon—the newly discovered island of Bermuda. The sight of land sparked euphoria, but no one could predict that this was only a brief stop on their journey through maritime hell.

On Bermuda, the crew spent several weeks repairing damaged ships and replenishing supplies, taking advantage of the island's abundance of fresh water and food. It was a blessing after months of deprivation, but Brennin knew that a longer stay could weaken morale and provoke another mutiny. By the end of June, they decided to set sail eastward again—toward the Azores, the gateway to Europe. The sailors were hopeful but unaware that the worst part of the journey still lay ahead.

The ocean was not about to make their return easy. A powerful storm struck the fleet in the open sea, proving fatal for one of the caravels—the Merope. Furious waves shattered the ship's hull, and its crew, unable to be rescued, vanished into the ocean's depths. The rest of the fleet, battered and scattered, endured weeks of grueling sailing. Finally, after two months of struggle, the last two surviving ships—the Aurora Magna and the Stella Maris—reached the Azores in August 1503 AD. Though exhausted and decimated, the surviving sailors knew they were finally close to home.

Sebastian Brennin, after months of hardship and danger, quickly left the Azores and headed to the capital of Memoriana—Gijón. He brought with him maps, logbooks, and samples of exotic plants and raw materials as proof of his discoveries.

His journey across the Atlantic had ended in success, but he knew the real battle was just beginning—he had to convince King Audoin III that his expedition was valuable and deserved further support. After weeks at sea, he finally stood before the monarch, ready to tell of the newly discovered lands, the natives, and their culture.

The king received Brennin coldly. While he listened attentively to the tales of the discovered islands, the natives of Haiti and the Caymans, the rich nature, and the possibilities of colonization, he was not overly impressed. Like the ruler of Adberia a few years earlier, Audoin III did not see in Brennin's discoveries a path to great wealth. His priority was finding a new route to Asia, to the lands of spices, silk, and gold—not discovering lands inhabited by "primitive" peoples who lacked these treasures.

Despite the cold reception, the expedition was not deemed a complete failure. The Memoriana monarch ordered further exploration of the newly discovered lands but was in no hurry to organize another expedition.

For him and his advisors, the New World was merely a marginal territory that could serve as a base for future voyages, not the primary goal of exploration. Brennin, though disappointed by the king's reaction, did not abandon his dreams of further expeditions. He knew that the discoveries he had made could be significant in the future—he just had to wait for the right moment

Portrait of Sebastian Brennin created by an unknown Memorian painter, early 16th century – (ChatGP)

Last edited:

- 1