Chapter CXLVIII: The Consequences of a Failed Death Ray Part I.

Chapter CXLVIII: The Consequences of a Failed Death Ray Part I.

There were a number of articles of faith underpinning British grand strategy in the early 1930s, some were ancient and abiding like the necessity of a strong navy, while others were more recent additions. Numbered amongst these newer articles was the maxim 'The bomber will always get through' and it had rapidly become one of the more influential and hotly debated ideas. While that particular formulation owes itself to a politician, specifically a speech the then Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin had made in 1932, the general idea had been discussed and debated for many years in both military and civilian life. The general fear was that in any future conflict enemy bomber armadas would swarm over their target unhindered and drop vast quantities of munitions on it. The threat posed by these bombers was often amplified by fears of what exactly might be inside the bombs they carried. While the use of chemical and biological weapons were de jure banned by the Geneva Protocol this treaty had entirely failed to prevent the use of chemical weapons in the Rif War, the Japanese using it on rebels in Taiwan, and most recently, the Italian attempts to use it in Abyssinia. Speculation that any future enemy would resort to such measures was therefore commonplace whenever the bombing threat was discussed. It should be noted though that even amongst those who believed the Geneva Protocol would hold (or that British threats of a similar response would deter the enemy from such escalation) there remained a pervasive concern that massed bomber attacks could lay waste to the country in short order and the 'morale blow' from this would force the country to sue for peace. The experiences of the Abyssinian War were seen by much of Westminster as supporting this belief; the RAF's Whitley bombers had successfully 'raided' Rome without a single loss and, had they been armed with bombs not propaganda leaflets, it was generally believed they would have devastated the city. The influence of this belief in the bomber can be seen in the other services, the Royal Navy and Army accepted the RAF view and incorporated it into their own planning. The Admiralty's debates over armoured carrier design and air power tactics, as discussed in Chapter CXXXVI, were in large part informed by the perceived difficulty of stopping incoming bombers. On land that same perception drove the Ministry of War to prioritise developing modern anti-aircraft weaponry over updating it's somewhat outdated artillery park; with the RAF unable to stop the bombers it would fall to AA weapons to defend key targets, which meant those weapons had to be modern.

The Chemical Defence Research Establishment (CDRE) at Sutton Oak in Merseyside. The British government had signed the Geneva Protocol against chemical and biological weapons but with a reservation; in the event of such weapons being used against Britain the government reserved the right to reply in kind. To make good that deterrent threat Britain needed modern chemical weapons and plenty of them, this dangerous and complex task fell to the staff of Sutton Oak. While it's more famous parent unit, the Chemical Defence Experimental Station at Porton Down, focused on researching new weapons and defences against them, the CDRE had the more specific role of developing the methods and processes required to manufacture the substances safely, economically, and in bulk. Situated in the heart of the Merseyside chemical industry cluster the establishment had seen major funding boosts during and after the Abyssinian War with the intention of updating and improving the methods that had been used in the Great War and starting construction of new production plants.

Inside the RAF the concept was more subtle than Baldwin's wording suggests, his speech had been made in the context of an upcoming disarmament conference and was more concerned with rhetorical efficacy than accuracy, though that caveat could be added to almost any political speech regardless of context. For the military the crucial point was not that interception of any individual bomber was impossible, but that you could not stop all of them and some number of bombers would always make it through to their target. Within the RAF it was accepted that the Rome raid had been an exception, taking advantage of Italian complacency and the limited resources of the Regia Aeronautica to essentially launch a surprise attack. It was expected that any follow up raids would have experienced far greater losses from the now alert Italian defenders, a reasonable belief given the panicked orders from Mussolini ordering fighters and anti-aircraft guns from the French border pulled back to defend Rome and other key targets. While this did help prove bolster the Air Staff's arguments about the psychological impact of heavy bombers and their value as a deterrent, it was not the same as an actual bombing campaign in terms of hard evidence particularly as the success had been achieved with what the Staff thought was a far too small bomber force. Frustratingly, from the point of view of the Air Staff at least, the civil war in Spain was refusing to develop a 'strategic' dimension in the air. Neither side was well equipped with heavy or even medium bombers and both were holding back from trying to hit targets in populated areas, let alone deliberate attacks on 'morale' targets. Given it would be their own citizens they would be bombing, and given the persistent belief by both sides that they would 'soon' make a breakthrough and end the war, this is understandable. It should be noted that the Air Staff had strongly argued that a short 'decisive' bombing campaign would force the Republicans to seek terms and end the war with fewer overall casualties. Uncomfortably for the Air Staff this put them alongside German advisors arguing for 'terror bombing' and the more excitable Falangists who would rather see a city destroyed than in enemy hands. Regardless of this it proved to be a counter-productive argument to make; the more the threat of heavy bombers was talked about, the louder the Monarchist high command demanded modern fighters to defend Madrid and the other major cities.

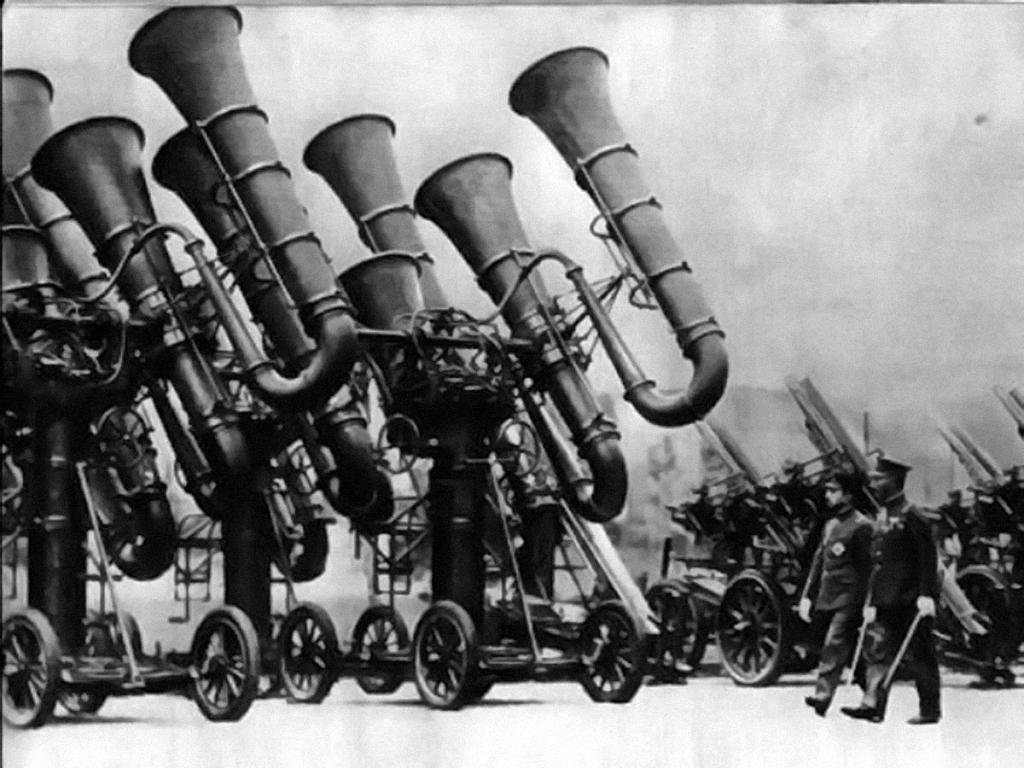

Sound mirrors at the Hythe Acoustic Research Station on the south Kent coast, on the left the 30ft and 20ft parabolic dishes (note the metal 'stick' on the 30ft dish that would have held the microphone), on the right the large 200ft mirror wall and it's rack of receivers. While the British had not invented sound ranging they were the first to make it operationally useful and the first to deploy it to detect aircraft, as early as 1915 work was underway on using sound to warn of incoming German bombers and Zeppelins. Essentially the sound mirrors collected and concentrated sounds towards a central microphone where the operator listened for the sound of aero-engines before passing a warning to the wider air defence network. A 200ft mirror had been built on Malta as part of that island's defence system and was used operationally during the Abyssinian War. The 'Il Widna' (The Ear) station was able to detect incoming aircraft up to 35miles away in the right conditions, a considerable improvement over the 5 to 8 miles the Great War era 20ft dishes could manage. Unfortunately along with range the larger mirror also scaled up the problems, background noises were also amplified and even ship engine sounds were detectable. It became apparent it took considerable practice for a listener to be able to reliably differentiate between aero-engines and ships. These issues could perhaps have been overcome, but fundamentally 35 miles of range was insufficient and in the post-Abyssinian review the Air Ministry abandoned the project to focus on more promising prospects.

In fairness to the Monarchists high command those demands were uncomfortably close to the Air Staff's own view on the subject. The RAF's fighter squadrons had borne the brunt of the initial post-Great War defence cuts, but when concerns grew about the 'Continental Air Menace' in the early 1920s the reaction was a large expansion of the fighter force alongside increasing the number of bomber squadrons. It is worth noting that, in the grandest traditions of British strategic thinking, the 'hostile' bomber fleet that prompted this large investment was that of the French, Anglo-French relations in the early 1920s having reverted to their natural level of suspicious mistrust. This position was not a political imposition from cabinet, but a decision the Air Staff had fully supported in principle, with an admit degree of squabbling about the detail. The RAF firmly believed in the ability of air power to win a war on it's own and was certain of the potentially devastating impacts of strategic bombing but that did not mean they saw no role for the fighter, quite the opposite. RAF doctrine did indeed hold that bomber squadrons should be as 'numerous as possible' but it also demanded that fighter squadrons be provided for defence of vital targets and to support morale on the home front. In a battle of attrition with both sides trying to destroy the industry and will to fight of the other side, an effective fighter defence was seen as a vital counter-part to the bombing campaign. Blunting the enemy's attacks, reducing the damage they caused, attriting the enemy bomber force and raising civilian morale by seeing friendly fighters in the skies above and AA guns defiantly firing away were all seen as valuable contributions. For the Air Staff you could not win a war with strategic air defence, but you could keep the country in the fight while the heavy bombers did. Naturally there was plenty of room for arguments within this framework around how many fighter squadrons were actually the bare minimum required, but a steady enough consensus was in place. This agreement was disrupted when the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence entirely failed to develop a death ray.

The planned Air Defence system for Great Britain as it stood before the Abyssinian War. Acoustic mirrors along the coast would detect incoming bombers, supplemented by observers on the ground, and they would feed the information back to their local operations room. These rooms would be in radio-telephone communication with the fighters patrolling in the pink Aircraft Fighting Zone which would be directed onto the incoming raid. This system overcame the limitations of acoustic/visual observation by having the aircraft already be at combat altitude and on patrol, though at the cost of leaving Dover and the East Coast ports relying on AA guns alone. Not shown on this map are the facilities that made it possible, the Y-stations which were responsible for wireless direction finding (D/F). Radio transmission from enemy bombers carrying out equipment checks and organising themselves could be detected and triangulated from hundreds of miles away, even if the messages themselves were encoded this was enough to warn that a raid was assembling. There was therefore no need for the fighters to remain on permanent patrol, a task that would require vast numbers of fighters and ground crew, as they could instead wait for a D/F warning before taking off.

The Air Ministry had been plagued by inventors claiming to have an aerial death ray since the early 1920s, to the point where there was a standing offer of £1000 to anyone who could demonstrate a working model capable of killing a sheep at 100 yards. Naturally this went unclaimed, but the general swirl of rumours about foreign powers developing such weapons went unabated, not helped by credible figures such as Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi claiming to have perfected the device or be close to it. In order to close off the matter the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence, also known as the Tizard Committee after it's chairman Henry Tizard, asked the head of the Radio Research Station, Robert Watson-Watt, to carry out a quick feasibility check on the concept in January 1935. A brief calculation confirmed unfeasible amounts of power would be required to make such a device work and that would have been that, had it not been for the suggestion from Watson-Watt's assistant Arnold Wilkins that while radio waves could not kill incoming pilots they may be able to detect the aircraft. The 'problem' of aircraft interfering with radio transmissions had been known since the early 1930s, the proposal was to use this hitherto undesired phenomenon to detect aircraft at greater distances. The potential use of radio waves for aircraft detection was not a particularly groundbreaking insight; Germany, the US, France and the Soviet Union all had research programmes based on the idea by the mid 1930s. What did mark out the British effort was the speed with which the programme was pushed and the funds committed to it, in mid January Wilkins produced the theoretical calculations on how detection might work and by the end of February a practical test was carried out. The 'Daventry Experiment' used a BBC radio transmitter and a GPO portable radio truck in a very lashed up system that nevertheless detected a Heyford bomber at several miles distance. Less than two months after that a permanent installation had been established at Orford Ness for overwater testing and by the autumn the range was up to 40 miles, a result the Tizard Committee and the Air Ministry felt was sufficient to justify stopping all funding for acoustic research, even if the sites themselves remained in operation as a stop-gap measure. In December of that year the Treasury agreed to fund five stations to form a Thames Estuary Chain to cover the southern and eastern approaches to London, construction started in 1936 and the first three sites were substantially complete by the spring of 1937. Long before then funding had been secured for 20 more stations to form Chain Home, which would cover the entire south and east coasts. Watson-Watt and Wilkins had not been idle in this time, working out of the newly established research station at RAF Bawdsey near Orford Ness they had pushed the detection range out to 100 miles and added a height finding function, vital information for the ground controllers to know. By August 1937 the sites were complete enough to be included in the RAF's annual air exercises, for the Air Staff this was where the problems began.

The transmitting towers at Air Ministry Experimental Station 04 Dover. To provide a degree of cover the sites were codenamed as experimental stations, similarly the method itself was referred to as Radio Direction Finding (RDF) in order to make it seem like a mere variation on existing direction finding systems. The stations themselves have been variously described as crude or even primitive, unfavourably compared to the systems under development in the US and Germany which used far shorter wavelengths so were theoretically more accurate and required far smaller aerials; the US SCR-270 required a 55ft antenna and the German Freya made do with a 6m (20ft) antenna, both were semi-mobile and could be relocated on a trailer, in contrast an AMES Type 1 aerial as installed at a Chain Home station needed towers 360ft tall. There was truth in these comparison but it was the result of a very deliberate compromise, Watson-Watt and Wilkins had used off the shelf components which were not as powerful as custom made items because they allowed faster development and rapid construction of the final system. As a result the UK would have Chain Home completed and integrated into the national air defence system long before either Germany or the US had a single one of their more complex sets out of development and ready for operational testing.

The summer air exercises generally focused on 'home defence', protecting the British Isles from an unspecified continental air threat. They were not just an RAF event, the Army would commit a number of it's searchlight and AA units, the Observer Corps would call in it's volunteers to get the posts manned and the Admiralty would send an observer or two, officially to monitor the plans for the aerial defence of key ports and unofficially to keep an eye on the junior service. The 1937 exercises would see the debut of a great many new innovations or developments which were finally able to be used together. On the intelligence and warning side there was of course the Chain Home RDF stations supported by 'Huff-Duff' (high-frequency direction finding) enabling friendly fighters to be tracked. Fighter Command's new control room at Bentley Priory was operational and the dedicated phone and teleprinter circuits had been added to connect it to all the various controls, groups and other elements. Finally in the air it was the first full scale exercise carried out with Spitfires and Hurricanes not biplanes and with pilots trained on the latest aerial warfare tactics brought back from Spain. While there had always been a master plan for how the various elements would work together, the so-called Dowding System, this would be it's first real trial. Naturally it did not start well, it soon became apparent that the Observer Corps and the RDF stations could generate an overwhelming volume of information and it was often contradictory. The plethora of phone lines proved to be woefully insufficient for the volume of information and were overloaded, forcing controllers to switch between receiving updates and being able to contact the airfields. The 'Huff-Duff' system required the pilots to make regular transmissions to enable tracking but they often forgot when distracted by flying and fighting their aircraft, though given the short range and temperamental nature of the radios this was often irrelevant. In the air, when an interception was managed it was clear that the lessons of Spain did not neatly transfer to the UK and the tactics and training required for interception, as opposed to zone patrolling, needed more development. And yet, when all the elements did come together the results were startling. In the final days of the exercise the defenders managed to intercept every incoming bomber and shoot down all of them. The bomber had not got through.

The first production Hawker Fury Mk.I, outside the Brooklands aircraft shed in the Spring of 1931. The highly polished surfaces are clearly visible, as is the large 'chin' air intake for the 525hp Rolls Royce Kestrel V-12 engine. It can also be seen that there are no wires for radios, because the original Furies were 'interceptors', stripped of all extraneous weight (such as radios) to maximise performance. The concept held that a Fury squadron would sit at readiness, wait until an incoming bomber was visually spotted, and then take off to chase them down, using their superior speed and rate of climb to catch them. The 1931 summer exercises proved this idea was a disaster in practice, even when the bombers were routed directly over the Fury squadron's airfields at Tangmere and Hawkinge the fighters still could not climb fast enough to reach altitude before the bombers had vanished from sight. The Interceptor concept was abandoned and Hawker developed the Mk.II Fury as a zone fighter, equipped with a radio and all the equipment for night flying operations. The experience of the 1937 exercises made the tacticians of Fighter Command wonder if RDF meant it was worth looking again at an interceptor.

Naturally this was contested by a somewhat panicked Air Staff, the bomber force had not had a chance to adapt to the new defences and clearly the best tactics against a patrol defence were not appropriate to overwhelm interceptors. Moreover the Spitfire and Hurricane were brand new aircraft going up against older designs, the 'proper' four engined heavy bombers being developed under the B.12/36 specification would fly faster, higher and be better protected. Fighter Command contested that they too had improvements coming; cannon armed fighters, improvements to Chain Home, new radios with automatic D/F, 'filter rooms' to help manage the flow of intelligence and more phone lines to improve communications. The scene was set for another internal RAF argument about the relative priorities of fighter vs bomber and quite which side would be more favoured by future technological developments. This well worn pattern was interrupted by the Air Council which not particularly innocently asked the question, what if our future enemy has or develops the same air defence capabilities? The Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Air, Sir Christopher Bullock, had never been entirely convinced of the Air Staff's obsession with the bomber offensive and saw in the exercises an opportunity to correct the balance. The Treasury could be relied upon to support this measure, a fighter being far cheaper than a bomber yet counting the same to a press and public (and many backbench MPs if one is honest) that looked only at the number of 'machines' the RAF had and not the composition of the force. The variable was the Air Minister Churchill, but once he received a positive report on the exercise and the potential of Chain Home from 'Prof' Lindemann he threw himself into the matter with his usual enthusiasm, much to the horror of the Air Staff.

---

Notes:

I hadn't actually intended to make this a two parter, but it got to a few thousand words and everyone had been so politely leaving the top of the page free I felt I should get something out before Christmas, and here we are. Apologies for not responding to each comment, but I assumed you would prefer an actual update.

The starting point for all this is a quote from Macmillan; "we thought of air warfare in 1938 rather as people think of nuclear war today". Once you look at it from that perspective the parallels are numerous, particularly in the language. Bomber Command had lively debates about the merits of strategic targets (cities and factories) versus counter-force missions (enemy airfields and logistic networks), deterring enemy bombers through the threat of your own bombers responding was a widely discussed strategy. The language is similar of course because it's the same people talking, the pre-ww2 squadron leader who went to Staff College and learnt this became the post-war air marshal developing doctrine for the cold war. The worries about chemical weapons are all OTL as is the CDRE and it's upgrades, there was a genuine belief that only the threat of chemical retaliation could deter their use. Given they were liberally used by the Soviets, Italians and Japanese, but only on people who couldn't use them back, this is not unreasonable. It is probably too simplistic to say Germany didn't use chemical weapons because they were worried about the Allies/Soviets using them back, but it absolutely has to be part of it and certainly must be a major part of why Japan used chemical and biological weapons freely in China but never anywhere else. They are never going to get used, may indeed never get mentioned again in the story, but you cannot understand the debate about bombers without acknowledging fears of bombers carrying gas or something worse.

I have tried to squeeze a good decades worth of involved strategic debate into a short section, but overall the point is that even the most obsessive 'bomber baron' never neglected fighter defence. If you wish to run a strategic air offence, and the RAF absolutely did, then you almost have to run a strategic air defence. hence the many defence schemes and experimentations with zone fighters, interceptors, acoustic mirrors and wireless intercepts. Indeed there is an irony that despite it's reputation the RAF put a lot more thought and effort into developing and improving it's fighter defence tactics, equipment and doctrine than it ever put into the bombers. As has been said the Battle of Britain was essentially a group of happy amateurs who relied on luck and things just working out going up against hard bitten professionals who had been training and honing their craft for years, and the RAF were the professionals.

The Army did start work on it's "modern" AA guns (the QF 3.7" for heavy and the 40mm Bofors for light) before it got it's artillery sorted. In large part because home defence was more important than equipping a new BEF for the politicians, but also because anti-aircraft guns were a big part of the Army's home defence role and at least under the pre-Radar plans a lot of ports and industrial centres were outside the 'fighting zone' and so were going to be relying on AA guns alone. This will be discussed a bit more in Part II because change is coming.

Radar development story is of course true, including the death ray and rewards for dead sheep. Watson-Watt had a fairly robust approach to engineering, his position was "Give them the third best to go on with; the second best comes too late, the best never comes." and of course in the context of Radar he was undoubtedly correct. The British could have developed more advanced systems to match the US and German efforts, but they never would have been ready in time. And bear in mind the target date was not summer of 1940, it took time to learn to use it, iron out the bugs and generally make it work. The US SCR-270 radar at Pearl Harbor is an example of what happens if you have superior technology but untrained operators and no air defence system behind it.

There were exercises with radar pre-war and they did indeed not go well but showed flashes of great promise, but in OTL it was Earl Swinton as Air Minister and Bullock had been sacked as PUS and replaced by an ex-Army major general with extensive experience at the Post Office. Which says a great deal about how important the Civil Service thought rearmament was. Here the 1937 exercises are still somewhat shambolic, but the flashes of promise remain. Enough to encourage Bullock to try and change strategy and for Churchill to get over-excited about, which always ends well.

Last edited:

- 5

- 2

- 1