5.5. THE GOTHIC WAR OF CONSTANTINE I AND THE OUTBREAK OF WAR BETWEEN ROME AND ŠĀBUHR II.

In 328 CE, as soon as weather allowed movement along the roads, Constantine I moved from Nicomedia (March 1, 328 CE), to

Serdica (modern Sofia, May 18, 328 CE) and reached

Oescus on the Danube (near the modern village of Gigen in Bulgaria, July 5, 328 CE). Here, in preparation for his forthcoming war on the Danube Constantine had previously given the order to build a bridge across the Danube (length 2,437m) between Oescus and

Sicida (modern Sucidava, in Romania). He continued his march west and reached

Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier in Germany, September 27, 328 CE), after which he, in the company of his son Constantine II conducted a successful campaign against the Alamanni. The war was continued under the nominal command of his son, but in truth by the experienced officers until ca. 331 CE, according to Yann Le Bohec.

Silver coin of Constantine I commemorating the building of Constantiniana Dafne on the left bank of the Danube. On the obverse: CONSTANTINVS MAX(imus) AVG(ustus). On the reverse, CONSTANTINIANA DAFNE. Mint of Constantinople.

Constantine I had also ordered the building of a fortress at

Constantiana Dafne on the left bank of the Danube the previous year. He also improved the ferry and road networks in the area, as attested by the milliary stones. The bridge was built in imitation of Trajan, whose architect Apollodorus had similarly built a huge wood and stone bridge over the Danube as a manifest signal of Roman power to all foreign peoples in the area. Camps and cities to be built on the other side of the Danube were also built as forward staging posts and assembly areas for his planned campaign, which was to be a large-scale offensive against the western Gothic people of the

Tervingi.

Map showing the geographical situation of the Wielbark culture (in red; I century CE - early III century CE) and the Chernyakhov culture (in orange; IV century CE). The association of the Wielbark culture with the Goths is not accepted by all scholars, but the Chernyakhov culture (and its Romanian offspring, the Sântana de Mureș culture) is firmly associated with the Goths.

This division of the Goths is first attested in 291 CE. They are mentioned occurs in one of the Latin Panegyrics traditionally attributed to Claudius Mamertinus, delivered in or shortly after 291 CE in front of the emperor Maximian. In it, Mamertinus said that the "Tervingi, another division of the Goths" (

Tervingi pars alia Gothorum) joined with the Taifali to attack the Vandals and Gepids. The term "Vandals" could have been a mistake for "Victohali" because around 360 CE Flavius Eutropius reported that Dacia was at the time inhabited by Taifali, Victohali, and Tervingi. According to Herwig Wolfram, these three peoples formed a coalition of sorts which fought the enemy coalition formed by the Vandals and Gepids for the control of what’s now today Romania, Slovakia and parts of eastern Hungary. The other division of the Goths, the

Greuthungi, is first named by Ammianus Marcellinus, writing no earlier than 392 CE and perhaps later than 395 CE and basing his account of the words of a Tervingian chieftain attested as early as 376 CE. While the Tervingi inhabited what is now Romania, Moldavia and southwestern Ukraine (and so they were immediate neighbors of the Roman empire along the lower Danube) the Greuthungi dwelled further west in what’s today central and eastern Ukraine. The Taifali inhabited what’s now the Romanian region of Oltenia.

In 329 CE Constantine I crossed the Danube in front of his armies and defeated the Tervingi Goths and the Taifali (according to Herwig Wolfram, it was in this occasion when Constantine deported part of their people to Phrygia). As a result, he was able to reoccupy part of the Dacian territory abandoned by Aurelian, and Constantine was celebrated as a new Trajan. Constantine was now expanding the empire by acquiring new buffer zones to protect the heartland provinces (the same function that was played by Armenia and northern Mesopotamia in the East). After the conclusion of the campaign, Constantine I reorganized the border defenses to reflect the new situation.

According to Christian Gothic tradition, "Gutthiuda" ("Gothic people" in the Gothic language) was the name of the land inhabited by the Tervingio and their allies/subjects (like the Taifali) on the left bank of the Danube.

Because of their defeat against Constantine I and the Roman occupation of what’s now Oltenia and Wallachia, the Goths turned their eyes towards what’s now Transylvania and Hungary, where traces have been detected by archaeologists of Gothic encroachment around this timeframe. This led to a conflict with the Sarmatians (who were Roman allies) in 331/332 CE in which the Tervingi Goths defeated the Sarmatians. But the joy of the Goths at their triumph was short-lived. Constantine I recalled his son Constantine II (who would have been 15 years old by now) from Gaul and together they led an invasion of the homeland of the Tervingi in 332 CE. The Tervingi were again defeated, even though Constantine I was nearly killed in an ambush by Taifali horsemen in which most of his personal guard perished. Zosimus claimed that the Taifali killed most of Constantine’s army, but this can be dismissed as wrong with just a look at the figures involved (500 Taifali horsemen).

Trapped between the Sarmatians and the armies of Constantine I, the Tervingi found themselves in dire straits (according to Roman historians, they suffered 100,000 deaths to hunger and frost the following winter between men, women and children) and took the unprecedented step to elect a “judge” (i

udex in Latin, k

indins in Gothic). Wolfram considered that the

kindins would have been a war leader who would have taken control over the whole Tervingi nation, as it found itself now in almost desperate circumstances. They chose as

kindins a certain Ariaric, who hurried to sign a

foedus with Constantine I; he also had to send his own son Aoric as a hostage to Constantine I and in exchange the Romans provided the surviving Tervingi with victuals. The

foedus also meant that henceforth the Tervingi Goths would provide foederati warriors for the Romans whenever required; according to Jordanes, the Goths were required to furnish 40,000 warriors for the terms of the

foedus:

In like manner it was the aid of the Goths that enabled him to build the famous city that is named after him, the rival of Rome, inasmuch as they entered a truce with the Emperor and furnished him forty thousand men to aid him against various peoples. This body of men, namely, the Allies, and the service they rendered in war are still spoken of in the land to this day.

According to Herwig Wolfram, when the Tervingi attacked the Sarmatians they had been led by a king (

reiks in Gothic) called

Vidigoia (he’s mentioned in one very convoluted and misplaced passage of Jordanes, who quoted the eastern Roman historian Priscus) who died in battle against the Sarmatians and who could have been a member of the House of Baltha. The Goths valued military success above all else and the House of Baltha had failed, and so creation of the office of

kindins could have been a result of the Balthi losing their reputation as successful war leaders.

The Greuthungi to the east though kept their previous ruler (

reiks) Geberich of the House of Amal. It is possible that one of the goals of Constantine`s campaign had been to split the Goths and if this was the case, he was successful. The Tervingi would not help the Greuthungi in 336 CE. The Tervingi were therefore treaty-bound to the House of Constantine until 367 CE while the Greuthungi were not. The scholar Charles R. Whittaker speculated that it is probable that the so-called

Brazda lui Novac (“The furrow of Novac the giant”, “Giant’s Furrow”, also known as “Constantine’s Wall”) in Wallachia, a ditch with a length of about 300 km was probably built by the Romans during Domitian’s reign, but was now reused by Constantine to mark the border of his conquests. Ilkka Syvänne suggests that Constantine’s original plan would have been to push the frontier this far, but that either he or his successor Constantius II decided to leave these territories to the Tervingi Goths in return for their service as foederati, the former being the likelier alternative because later in the IV century CE the Tervingi held Constantine the Great in high esteem.

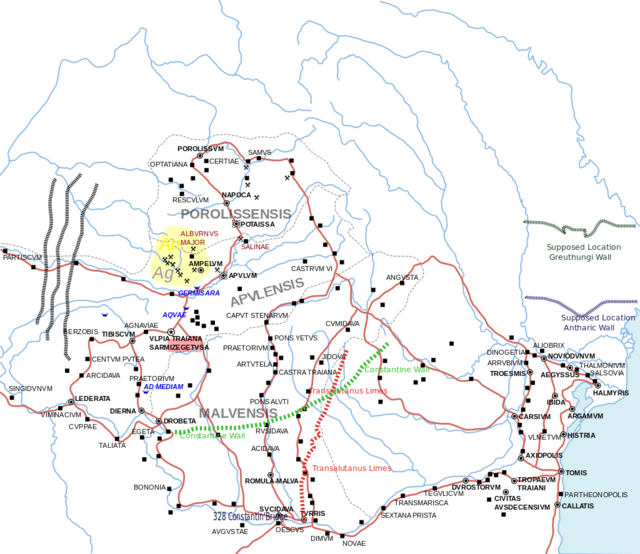

The "Giant's Furrow" is indicated in green in this map.

According to Jordanes, in 333/4 CE the Greuthungi Goths made a retaliatory attack on behalf of their brethren against the Sarmatians for their actions in 332 CE. This time the Goths were successful, because Constantine did not attack them from behind. According to classical authors, the Sarmatians who inhabited what’s now the Hungarian plain (the

Iazyges) were divided into

Agaragantes (“free Sarmatians”) and their “slaves” the

Limigantes (“unfree Sarmatians”). Probably because they were not expecting any help from Rome, the Agaragantes took the dangerous step of arming their subjects, the Limigantes but were still defeated by the Greuthungi. This resulted in the uprising of the Limigantes against their overlords; they defeated the Agaragantes with the result that one part of them fled to the Vandals/Victufali for safety while most of them fled to Roman territory, where Constantine settled them as foederati in 334 CE. At the same time Constantine probably defeated the Limigantes as a result of which he took the title

Sarmaticus Maximus.

According to Jordanes the Greuthungi king Geberich also engaged in battle the Vandal king Visimar on the bank of the river

Marisos. According to Ilkka Syvänne, this could suggest that the Goths had pursued the fleeing Sarmatians. The Vandals were badly defeated and their king Visimar died battle, and as a result the remnants of the Vandal army collected their families and asked Constantine to settle them in Pannonia. Constantine I acquiesced to their demands and they were also settled as

foederati in Pannonia, where they served the Romans for about sixty years, until Stilicho summoned them and sent to Gaul. It is difficult though to know what Jordanes meant by “Pannonia” because there is no evidence for the presence of large numbers of

foederati Vandals on Roman territory. However, if he meant that these Vandals migrated together with the Sarmatians into Roman territory or that they were allowed to settle the “barbarian” portion of Pannonia on the left bank of the Danube under Roman protection then that could be plausible.

According to the

Anonymus Valesianus, the Romans transferred a total 300,000 Sarmatian fugitives into Thrace, “Scythia” (Lower Moesia), Macedonia and Italy. C.R. Whittaker connected the building or at least the reinforcement of the massive Devil’s Dyke in what’s now eastern Hungary, which consisted of 700 km of earth ditches, with Constantine I’s campaigns against the Sarmatians in 322 CE and 334 CE. Ilkka Syvänne suggested that the Romans would have considered the territory between the Danube and the so-called Devil’s Dyke to be part of the Roman empire in such a manner that the peoples inhabiting it, who were mainly the Sarmatians, were Roman

foederati and therefore also under Roman protection.

The black discontinous lines on the right part of this map of ancient Pannonia are remains of the "Devil's Dyke".

According to the traditional dating of the reign of the Aksumite king ‘Ezana, he reached maturity in about 327/328 CE after which the Christian Roman Frumentius who had acted as regent during his minority resigned and travelled to Alexandria where he reported the situation to the patriarch Athanasius and stated that Aksum needed a bishop. Athanasius suggested that this person should be none other than Frumentius, who already knew the country. Consequently, Frumentius was appointed to the post and returned to the Aksumite kingdom. This created a precedent according to which the patriarch of Alexandria would appoint an Egyptian Christian as head of the Aksumite (and later Ethiopian) Church. After ‘Ezana’s conversion to Christianity, undoubtedly at the instigation of Frumentius, the precedent set by Frumentius’ appointment suited the Aksumite King of Kings, because the Egyptian Christians were foreigners and therefore entirely dependent upon the support of the ruler.

The alliance between Rome and Aksum proved to be mutually beneficial. The surviving inscriptions suggest that the ‘Ezana conducted a series of campaigns against those who threatened the trade routes to the Roman empire in the Indian ocean (a trade from which Aksum also owed its own prosperity). He fought against the Blemmyes and Meroe (probably after they had revolted against their subordinated status as Aksumite vassals) probably in 328-329 CE and conducted a maritime campaign from “Leuke Kome” to the land of the “Sabateans” (which scholars identify with the Himyarite kingdom in southern Arabia) as a result of which the Arabs and “Kinaidokolpitas” were subjected to tributary status; this latter campaign occurred at some point in time between 329 CE – 332 CE. ‘Ezana’s campaigns had two consequences: it subjected the coastal areas to tributary status and secured seaborne communications, and it weakened the Himyarites, which perhaps enabled the Arab

foederati of Rome to reassert their control in central Arabia. Another result of the aforementioned campaign in southern Arabia was also the sending of high-ranking hostages by the Hymiarites, Omanis and Dibans to the court of Constantine I, which basically implies a direct Roman participation (or at least a very marked interest) in ‘Ezana’s campaign.

But while Constantine I was busy gaining victories in the Danube and extending Christianity outside the borders of the Roman empire, things took a turn for the worse in Armenia. Around 330 CE king Tirdad III of Armenia, Rome’s ablest and most loyal ally in the East, was poisoned by a nobiliary cabal according to Moses of Chorene (who spent a whole chapter of his History of the Armenians bemoaning the death of the first Christian Armenian king in biblical undertones, but failed to give any useful information about who poisoned the king and who were the plotters).

Map of Armenia and the southern Caucasus ca. 300 CE, after the First Peace of Nisibis.

Tirdad was succeeded by his son

Khosrov, who soon showed himself unable to control the situation and Armenia descended into anarchy. The events that happened following his accession to the Armenian throne are told by Moses of Chorene and Faustus of Byzantium, whose accounts agree in all the important points. Immediately after the accession of Khosrov, some of the main nobiliary clans of Armenia began a civil war among themselves. According to Moses of Chorene:

He (i.e. the patriarch Vrt’anēs) mourned over this land of Armenia, which remained in anarchy as the princely houses had risen against each other in mutual slaughter. Thus, the three families called Bznuni and Manazavean and Orduni were exterminated by each other and disappeared.

Moses of Chorene’s also wrote that the inhabitants of

Tarawn devised a plot to murder the patriarch Vrt’anēs (which failed) and Faustus of Byzantium adds the detail that the queen (the wife of Khosrov) encouraged the plot. This could be a signal of some sort of reaction against the adoption of Christianity by king Tirdad, and some scholars think that this could have been the main reason behind the poisoning of said king, and the infighting among the Armenian nobility.

Moses of Chorene follows by telling that just before his death king Tirdad had sent a bishop called Gregory (not to be confused with Gregory the Illuminator) “to the northeast lands” (without clarifying if said lands were or weren’t part of the kingdom of Armenia), accompanied by a certain Sanatruk, who was a member of the Arsacid royal house of Armenia and so a relative of Tirdad. The rest of Moses’ tale clarifies things a little: upon receiving the news of Tirdad’s death and Khosrov’s succession, “the same Sanatruk and some other men among the ever-faithless Aluank” murdered bishop Gregory “in the plain of Vatnean near the Caspian Sea”. “Aluank” was the Armenian name for the inhabitants of Caucasian Albania, which means that the Albanians had decided to join the Armenians and Iberians in their adoption of Christianity and had asked Tirdad to send a bishop to them. But Tirdad’s death changed everything, and Sanatruk (Tirdad’s relative and representative in Albania) revolted and proceeded to seize the city of P’aytakaran in eastern Armenia, where he crowned himself king:

Sanatruk, crowning himself, occupied the city of P’aytakaran and with the support of foreign nations planned to rule all over Armenia.

Who were these “foreign nations” is unclear; but judging from the rest of Moses’ tale and the fact that Sanatruk moved into Armenia from Albania, they were probably Albanians and perhaps trans Caucasian nomadic peoples like the Alans. Upon seeing Sanatruk’s usurpation, a certain

Bakur, who was the

bdeashkh (the Armenian version of the Iranian title of

bidakhš) of

Aḷdznik, also rose in open revolt and proclaimed himself king (although unlike Sanatruk he was not an Arsacid) and called the Sasanian king for help, thus opening the doors of Armenia to Šābuhr II. The

Šāhān Šāh had been waiting for such an opportunity for years, and he immediately seized it, and in 335 CE he sent an army into Armenia commanded by a certain prince

Narsē (whom modern scholars consider to have been a member of the House of Sāsān and maybe even a brother of Šābuhr II) to support Bakur. With this act, Šābuhr II effectively broke the peace treaty of Nisibis and started a war that (with a ten-year hiatus in the middle) would last until 363 CE. The revolt of Bakur is especially interesting because Aḷdznik is the Armenian name of

Arzanene, one of the five Armenian satrapies that the 299 CE Treaty of Nisibis had put under Roman control; what’s unclear is if Roman Arzanene included all of Armenian Aḷdznik or just a part of it. If all of Aḷdznik was part of the Roman empire, that would have meant that its

de facto ruler under Roman suzerainty was also a vassal of the Armenian king (a condominium of sorts); if that’s the case, in sending troops there Šābuhr II was not invading Armenian, but Roman territory. It’s also somewhat strange that a magnate of a province situated in the southwestern corner of Armenia, far from the Sasanian border and adjacent to the Roman empire, chose to run such a risk without being very sure that he was going to get help; in other words, Šābuhr II was probably behind this uprising from the beginning.

The chronology of all these events is extremely confused (Faustus of Byzantium and Moses of Chorene provide no dates). The death of Tirdad III is usually dated to 330 CE, and the next episode in the “Armenian troubles” according to the chronicles of Moses of Chorene and Faustus of Byzantium happened in 337 CE at the very earliest: patriarch Vrt’anēs and some nobles (Mar, lord of Tsop’k’ and Gag, lord of Hashteank’) wrote a letter to emperor Constantius II, asking for help. As Constantine the Great died in May 22, 337 CE, this gives a firm date for this letter: the late spring or summer of 337 CE at the very earliest.

By then, Armenia had spent seven years in a state of growing anarchy and had been openly invaded by a Sasanian army. Illa Syvänne dated the Sasanian invasion in help of Bakur of Aḷdznik to 336 CE, based on the Roman reactions to the Armenian crisis, but it’s just an educated guess. What were the Roman reactions to the internal disintegration of their most important ally in the East?

At first, there was little that Constantine I could have done, while the war in the Danube kept going on. But Illka Syvänne also speculates about the possibility that Constantine I decided to stop his support for Khosrov, due to his inability to keep his kingdom in order, to his possible pro-pagan proclivities (if Faustus of Byzantium is right about the king having supported the plot to murder the patriarch) or both. There’s a further reason to believe that Constantine I had taken another of his drastic, unorthodox decisions. In 335 CE, when he raised his nephew Hannibalianus to the dignity of

caesar, instead of giving him a set of provinces to administer (like he did with Dalmatius) he invested him with the title of

Rex Regum et Ponticarum Gentium (“King of Kings and of the Pontic People”). In other words, Constantine I intended to put his nephew Hannibalianus on the Armenian throne, ending the rule of the Arsacid dynasty (by the way, this was something that no Roman emperor had done before, and as far as I know, no later emperor ever repeated this experiment).

Bronze follis of Hannibalianus. On the obverse: FL(avius) HANNIBALLIANO REGI. On the obverse, SE-CVRITAS PVBLICA, with the personification of the river Euphrates reclined. Mint of Constantinople.

It’s because of this that Ilkka Syvänne dated the Sasanian invasion of Armenia to 336 CE. The Sasanian king invaded Armenia when he learned about Constantine I’s intentions for this kingdom. Of course, appointing Hannibalianus as

Rex Regum was an added, gratuitous insult against the Sasanian monarch. But by 336 CE, the situation along the Danube had finally been settled victoriously for the Romans; Constantine I had crossed the Danube with his field army once more, and it’s possible that this time he defeated the Greuthungi (the only powerful enemy that remained undefeated north of the Danube. King Geberich also died at this time, perhaps in battle (Jordanes only tells laconically that Geberich died soon after having defeated the Vandals in 334 CE and was succeeded by Hermanaric as king of the Greuthungi), and Constantine I was hailed as

Dacicus Maximus and was again acclaimed as a new Trajan.

Now, Constantine I was completely free to turn all his forces against Šābuhr II. At about this time in 336 CE the Taifali who had been settled/deported to Phrygia as

foederati revolted, but they were duly crushed by the

magister Ursus, who had been sent to the scene by Constantine I. There was also a minor Jewish revolt in Palestine (probably caused by the renewal of anti-Jewish legislation by Constantine I), and a minor anti-Christian revolt in Cyprus.

The Sasanian commander Narsē launched his invasion of Armenia and Mesopotamia together with Bakur of Aḷdznik in 336 CE and managed to capture the Roman fortified city of Amida (modern Diyarbakir, in Turkish Kurdistan), which was a serious setback for the Romans. The speed with which the Sasanians reacted to Constantine I’s actions and the success of their invasion is probably a telltale sign that Šābuhr II had been preparing for war for some time, stockpiling resources, weapons and money for the oncoming campaign. This is stated explicitly in one of the

Orations of Libanius of Antioch:

Therefore, I wish to say this in a somewhat concise fashion, as to be clear to all, namely, that they did not come to war for a trifling purpose. What was being done by the Persians was not peace but a delay in war, and they did not even desire peace, so they should not fight a war, but they loved peace so as to fight a proper war. They were not even altogether shunning the running of a risk, but in preparing for the magnitude of the dangers they mixed after a fashion peace with war. They offered a peaceful appearance but had the disposition of men at war. For when they were caught unprepared and were heavily defeated in earlier times, they did not blame their own good courage, but they cited as the reason their deficiency of preparation. They agreed to peace for a preparation of war, and continued indeed to acquit their obligations towards the treaty from that time onwards through embassies and gifts but arranged everything towards that purpose. They equipped their own forces and brought their preparation to perfection in every form, cavalry, men-at-arms, archers and slingers. They trained to a consummate degree what methods had been their practice from the beginning, but those of which they did not have the understanding they introduced from others. They did not give up their native customs but added to their existing methods a more remarkable power. But hearing that his forefathers Darius and Xerxes had measured out their preparation for ten years against the Greeks, he despised them for an inadequate attempt; he himself resolved to prolong the period to four decades. During the occurrence of this interval there was gathered a mass of money and there was collected a multitude of men, and a stock-pile of arms was forged. But already he had collected a stock of elephants, not just for empty show, but to meet the needs of the future. Everyone was warned to dismiss all other pursuits and practice warfare; and the old were not to depart from arms and the youngest were to be enrolled; they handed the care of the fields to their women and passed their life in arms.

Libanius was a rhetorician, but this text is not considered to be a mere rhetorical exercise, because what Libanius describes matches very well what seems to have been the personality of Šābuhr II, with his attention to detail, proper preparation of forces and stockpiling of resources. This is also the first time when the use of war elephants by the Sasanian army is firmly attested in a contemporary source (and it’s corroborated by Ammianus). Another fragment of this very same Oration adds even more interesting details about the “armaments program” of the Sasanian king:

For he did not consider it was second to any other as regards the production of manpower, but he found fault with the country because it did not arm the courage of its manpower by revealing a domestic source of iron. The sum of the matter was that he understood how to govern men but that his power was defective through the shortage of equipment (implements). When, therefore, he sat and considered this and fretted over it to a very great extent, he came to the decision to enter upon a deceitful and treacherous path and sent an embassy and became flattering, as was his practice; he made obeisance through his envoys and asked for a great supply of iron, under the pretext that it was for use against another nation of neighboring barbarians, but in truth he had decided to use the gift against the donors. But the emperor was well aware of the real motive, for the nature of the recipient caused suspicion. But knowing exactly in what direction the benefits of the technology were leading, though it was possible to resist, he gave with eagerness and saw through his reasoning all that would happen as if it had already occurred, but he felt shame at leaving his son enemies who were unarmed. He wanted every excuse of the Persians to be refuted first, but he blocked off his opponents to a nicety, so that although they flourished in all aspects they would be brought low. For the splendor of those defeated contributes to the glory of the conquerors.

The emperor readily gave with this magnanimity and hope(s) as wishing to make plain that even if they exhausted the mines of the Chalybes, they would not appear superior through this to the men by whom they were rated as inferior. But thereupon the preparation of the Persian king was complete both from native resources and from external supplies. Some supplies existed in abundance and others had been added surplus to requirements. Indeed, darts, sabers, spears, swords and every warlike implement were forged in a wealth of material. When he examined every possibility and left nothing not investigated, he contrived to make his cavalry invulnerable, so to speak. For he did not limit their armor to helmet, breastplate and greaves in the ancient manner nor even to place bronze plates before the brow and breast of the horse; but the result was that the man was covered in chain mail from his head to the end of his feet, and the horse from its crown to the tip of its hooves, but a space was left open only for the eyes to see what was happening and for breathing holes to avoid asphyxiation. You would have said that the name of ‘bronze men’ was more appropriate for these than for the soldiers in Herodotus. These men had to ride a horse which obeyed their voice instead of a bridle, and they carried a lance which needed both hands, and had as their only consideration that they should fall upon their enemies without a thought for their action, and they entrusted their body to the protection of iron mail.

Again, this fragment is more than just empty rhetoric. To cut Libanius’ tirade short: Šābuhr II bought iron to the Romans to equip his forces. This is again true, because strange as it may seem for such a large country, there were no iron mines in ancient times in the Iranian plateau. Iron had to be imported either from the west (there were iron mines in Armenia) or from the east, especially from India, where at that time a sophisticated tradition of metallurgy had developed and where the Iranians could purchase not only iron, but high-quality steel for their more expensive weapons (like swords for the royalty and nobility). Small amounts of even higher-quality steel came via the Silk Road from China, were the Chinese had been producing steel in large amounts for centuries.

Libanius says that Constantine I allowed Šābuhr II to buy iron in the Roman empire (the sale of weapons or materials able to be used for making weapons had been strictly controlled by Roman emperors since the times of Augustus, especially along the border with the northern “barbarians”) because he deemed to be below his dignity to fight an unarmed opponent. Obviously, this is rubbish (in this oration, Libanius was sucking up to Constantine’s son Constantius II), and the real reason can’t have been other than the fact that Constantine I saw no harm in allowing so. According to the ancient sources that described his campaigns and victories, Constantine I always emphasized mobility and speed over armor protection in his troops, and his soldiers (both infantry and cavalry) were usually less armored than those of his enemies. At the battle of

Augusta Taurinorum (Turin) against Maxentius in 312 CE, Constantine defeated Maxentius’ heavily armored

clibanarii with the employment of lightly armored clubmen who used their mobility to attack the cavalrymen at short distance. This preference of Constantine I for lightly armed but aggressive and mobile forces could have been the main reason behind his creation of the units of

auxilia palatina, which were formed mainly by Germanic mercenaries recruited along the Rhine, and which fought alongside the legions in the line of battle despite their lighter equipment.

Obviously, Šābuhr II thought differently. The description of the Sasanian “super-heavy” cavalry by Libanius accords to a point with the descriptions of Sasanian cavalry by Ammianus Marcellinus (who was an officer in the eastern army for many years in the wars between the Romans and Šābuhr II, and so was a direct witness). Despite Constatine I’s indifference towards armor, it’s clear that this new super-heavy cavalry of Šābuhr II impressed the Romans enormously, as it’s obvious from the accounts of both Libanius and Ammianus, and the fact that Constantius II began to copy it once he was the ruling

augustus in the East.

This development seems to have been enforced by Šābuhr II expressly to deal with the Roman army and its tactics. Military historians consider that this Sasanian preference (which reversed the trend followed by the Sasanian army since the times of Ardaxšir I, whose cavalrymen appear less heavily armored than Parthian ones in his rock reliefs) for heavily equipped cavalry lasted for the rest of the IV century CE but was reversed under the rule of Bahrām V in the V century CE, when the wars against the Hephtalites in Central Asia imposed a return to lighter, more mobile cavalry with a higher focus on archery and less focus on shock and impact tactics.

Bust of Constantius II.

Modern scholars believe that Constantine I had also decided to seize the initiative in the oncoming war and that the elevation of Hannibalianus had been planned in advance. Irfan Shahid speculated that Constantine I’s campaign plan envisioned two armies striking against the Sasanian empire. His plan entrusted the

caesar Constantius to command an army based at Antioch and his nephew Hannibalianus to command a second army in Cappadocia. Constantine I would take the field in person as commander-in-chief to direct and coordinate operations. According to Shahid, his ultimate goal after defeating Šābuhr II would have been to replace him with Hannibalianus. As David S. Potter pointed out, this arrangement was unique: “No other previous emperor had made plans for succession that depended upon the occupation of new territory or installation of a relative upon a foreign throne”. This uncommon act of Constantine I is mentioned in the anonymous Epitome de Caesaribus:

They (i.e. sons and relatives of Constantine) individually governed these regions: (…) Hannibalianus, brother of Delmatius (sic) Caesar, Armenia and the surrounding peoples.

Also, in the

Anonymus Valesianus:

He (i.e. Constantine) (…) created Dalmatius’ brother, Hannibalianus, King of Kings and ruler of the Pontic tribes, after giving him his daughter Constantina in marriage.

And finally, in the anonymous

Chronicon Paschale:

And Hannibalianus he (i.e. Constantine) appointed as king and put on him the purple cloak and sent him to Caesarea in Cappadocia.

In an essay by the American scholar Walter E. Kaegi based upon John Lydus’ VI century CE summary of Constantine I’s fourth century records, the Romans were planning a surprise attack against the Sasanians in 337 CE. Constantine I’s plan involved a two-prong attack with one army attacking through Armenia and a second army attacking through Mesopotamia.

Julian told in his oration

In Honor of the Emperor Constantius, written ca. 355 CE, that when the

caesar Constantius assumed command of the newly assembled Army of the East in 335/336 CE, it was unprepared for war. Training had been relaxed and recruitment had declined. Units were not fully manned and military supplies had not been stockpiled. Constantius recruited or drafted veterans’ sons of military age and implemented training and drill for the infantry. The cavalry was expanded with new

cataphractarii regiments, and supplies were stockpiled. In this first campaign, Constantius II already deployed at the young age of 19 the capacity for meticulous planning and preparation that would characterize all his campaigns.

Map of the area between Amida (the red mark near "Ad Tygrem) and Tigranocerta, with the main Roman roads. The battle of Narasara took place thirteen Roman miles east of Amida, according to Ensslin.

As the Sasanian invasion of Armenia and Mesopotamia led by Narse took the Romans by surprise, the

caesar Constantius was forced to react and to act on his own without the support of any other Roman armies further north. This was the start of a bitter personal rivalry between Šābuhr II and Constantius II that would last under the death of the latter in 361 CE. Despite his young age the

caesar Constantius took the field and he (or his generals) managed to inflict a crushing defeat on the Sasanian invasion army at

Narasara in Mesopotamia, in which the enemy force was annihilated and its commander prince Narsē was killed. Not much is known about this battle, as only two extant sources mention it. One is a brief mention in Festus’

Breviarum:

Nevertheless, at the battle of Narasara where Narses was killed, we (i.e. the Romans) were the winners.

And the other is Theophanes’

Chronographia:

In this same year (i.e. 336 CE), Narses, the son (sic) of the Persian king, overran Mesopotamia and captured the city of Amida. The Caesar Constantius, son of Constantine, made war on him; and suffered minor setbacks. Eventually he inflicted such a defeat on him in battle that Narses himself was killed.

Let’s stop here for a moment, because the battle of Narasara is one of the most overlooked battles between Rome and

Ērānšahr, but it’s also of the most resounding victories achieved by a Roman army against a Sasanian army in open field. Practically nothing is known about this battle because the part of our main source for the war between Šābuhr II and Constantius II (Ammianus Marcellinus’

Res Gestae) is missing. But judging from later references in Ammianus’ texts and other authors, Constantius’ victory was important enough to instill fear in the Sasanian king for the martial qualities of the Roman field army, when commanded by Constantius II, During the following fifteen years of war, Šābuhr II would always carefully avoid open battle against Constantius II’s

praesentalis army. W. Ensslin identified the place of the battle with the station of

Nararra (Ensslin identified it in 1936 with a place called “Nehar Harre” which I’ve been unable to locate) on the road from Amida to Tigranocerta, thirteen Roman miles east of Amida. Looking at the map of this area (supposing that Ensslin’s guess is correct), we can see that this tract of land is a rocky plateau crossed by small streams which flow from north to south into the Tigris (which runs on a west to east direction south of Amida). The abundance of water courses and deep ravines could suggest that Constantius could have outmaneuvered Narsē and managed to attack the Sasanian army with its back against a river or a ravine, which was historically a recipe for catastrophe for any Iranian army, as it negated its strongest point: the ability to deploy its superiority in cavalry by keeping it confined by topographical obstacles. In such a situation, usually a Sasanian army was easy prey for the closed ranks of Roman infantry, and with its escape route cut any defeat would end in a massacre.

View of the valley of the Tigris river from the walls of Amida.

The ancient city of Amida is the modern city of Diyarbakir, the capital of Turkish Kurdistan. The ancient ealled perimeter has arrived intact to our days, and despite later restorations and reforms in late Roman/Byzantine and Islamic times, it's still basically the same perimeter of walls that was built by Diocletian and rebuilt/reinforced by Constantius II. The walls are impressive, extremely thick and strong, and built of basalt (abundant in the area) which is one of the hardest rocks existing. These were the walls that would put up a sout resistance during the 73-days long bloody Sasanian siege of 359 CE.

After his victory, Constantius retook Amida and rebuilt its fortifications in a much-improved way, furnishing the walls and towers which ballistae and other war machines. These fortifications would resist years later against one of the most brutal sieges of the war between Constantius II and Šābuhr II. This rebuilding of Amida’s walls is mentioned by Ammianus Marcellinus:

The city (i.e. Amida) was once a very small one, till Constantius, when he was caesar, surrounded it with strong towers and stout walls, at the same time that he built another town called Antinopolis, so that the people in the neighborhood might have a safe place of refuge. And he placed there an arsenal of mural artillery, making it a formidable redoubt, as he had wished it to be called by his own name.

And in the anonymous Syriac text, the

Life of Saint Jacob the Recluse:

After the Emperor Constantius, son of Constantine the Great, had built Amida, he loved it more than all the cities of his empire and submitted to it many lands, from Reshaina (sic) as far as Nisibis and also the land of Maipharqat and of Arzon and as far as the frontiers of Qardou. Because these lands were on the Persian frontier, Persian brigands made continual incursions into these territories and devastated them.

At this moment, thanks to Constantius’ victory at Narasara, the Romans had repulsed Šābuhr II’s offensive and had seized the strategical initiative. The situation was excellent to launch the large-scale invasion of the Sasanian empire on two fronts that (according to some modern scholars) Constantine I had been planning. Constantine left Constantinople by sea and made a stop at Soteriopolis/Pythia to enjoy the hot-springs. According to one story, probably spread by Constantius II and his supporters later, he drank there a poisonous drug mixed by his half-brothers after which he reached Nicomedia, where he fell ill and then after a long illness died in May 22, 337 CE., being baptized by the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia on his deathbed. His son Constantius had hurried from Antioch to be beside his father when he died. Just like Julius Caesar, Constantine I had died before he could fulfill his dreams of eastern conquest, following the steps of Alexander the Great. The death of Constantine I put an end to the campaign against the Sasanian empire before it began.