8.9 FROM THE BATTLE OF CTESIPHON TO THE BEGINING OF THE RETREAT.

8.9 FROM THE BATTLE OF CTESIPHON TO THE BEGINING OF THE RETREAT.

After the fall of Maiozamalcha, the Roman army crossed a series of canals, and an attempt to stop them by the Sasanians was foiled (Ammianus XXIV, 4, 31). The relative ease with which the Roman army reached the outskirts of Ctesiphon is briefly mentioned in many other sources, like Libanius’ Epistle 1402, 2–3, Eutropius X, 16, 1; Festus, Breviarium, 28, p. 67. 18–19; Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration V,9; Socrates, III, 21, 3, Sozomenus VI, 1, 4, Malalas, XIII, pp. 329, 23–330 and Zonaras, XIII, 13, 1.

At this point, the Roman army reached the western bank of the Tigris, the location of the twin cities of Vēh-Ardaxšīr (called Coche or Kōḵē in Syriac Christian texts, or Māhōzē in the Babylonian Talmud, and still called anachronistically “Seleucia” by Greek and Latin authors like Libanius or Ammianus)on the western bank of the river and Ctesiphon (Middle Persian Ṭīsfūn) on its eastern bank. Ctesiphon has never been excavated, and Vēh-Ardaxšīr was only excavated briefly in the late 1920s by an American team and later in 1964 by an Italian one which managed to draw a map of the southwestern quarter of the city.

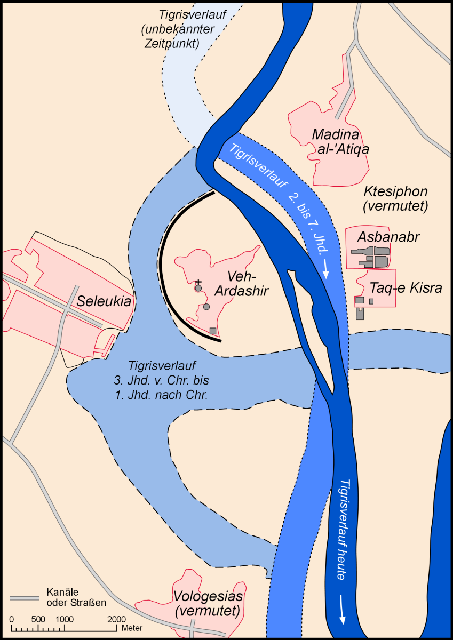

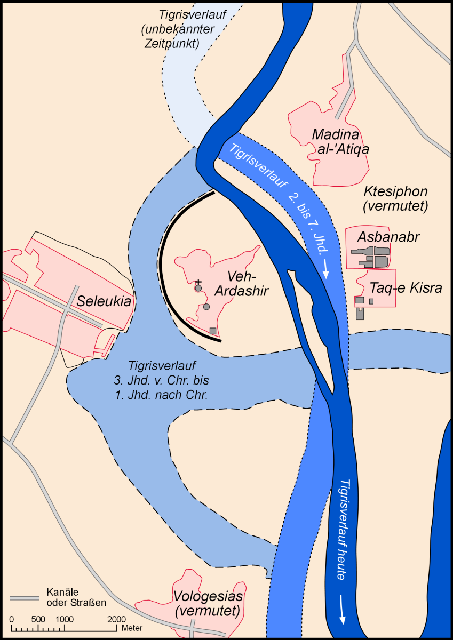

Reconstruction of the surroundings of Ctesiphon / Vēh-Ardaxšīr in Late Antiquity. The riverbed of the Tigris has changed significantly across the centuries. The westernmost course is the one that existed from the III century BCE to the I century CE, and as you can see, it reached the Hellenistic foundation of Seleucia; while Ctesiphon (founded by the Arsacids in the II century CE stood quite far removed on the eastern bank of the river. Vologesias / Walagašapat was founded by the Arsacid king Vologases I (Walagaš in Parthian, Walāxš in Middle Persian and Balāš in New Persian and Arabic) in he second half of the I century CE, probably after the Tigris changed course and left Seleucia without its river port. Vēh-Ardaxšīr was founded by the first Sasanian Šahān Šāh Ardaxšīr I in 230 CE just opposite the river from Ctesiphon, since then the Tigris has again changed course and now its riverbed crosses almost straight through the center of the ancient city. The irregular pink shape in the map is the excavated area of the old city, and the thick black line the part of the ancient wall that has been discovered (and which has led archaeologists to believe it was a “round city” as many other Arsacid and Sasanian foundations.

Based on the Italian excavations, Vēh-Ardaxšīr was a typical Sasanian city, built on a round plan and was heavily fortified, with circular walls studded with semicircular towers at regular intervals of 35 meters. The wall was very thick (10 meters wide at the foundations) and was protected by a wide moat, probably filled by water and built in mudbrick; all in all strikingly similar to the fortifications of better-known Central Asian cities that were also part of the Sasanian empire (permanently or temporarily) like Merv or Balḵ. From Christian and Jewish texts, we also know that the city had a citadel (known in Middle Persian as Grondagan or Garondagan, and as Aqra d’Kōḵē in Syriac) where the Sasanian governor, functionaries and garrison resided. The city lodged also one of the royal mints of the empire (Ctesiphon had another).

According to Tabarī, two bridges united Vēh-Ardaxšīr with Ctesiphon (one of them built by Šābuhr II early on his reign). Nothing is known for sure about Ctesiphon proper, as the German excavations before the WWI and the American ones in the 1920s only covered the Aspanbar area south of Ctesiphon proper, where in the VI century Khusrō I and his successors built the great palace of which still stands the throne hall, as well as pleasure gardens, walled hunting grounds, and where the members of the Sasanian court also built their private palaces near the royal residence. But all this did not exist yet in 363 CE, Ctesiphon proper is supposed to have been another walled city built on a round plan as was typical of Arsacid and Sasanian foundations, following the Central Asian custom. Inside the walls stood the “White Palace”, the palace of the Sasanian kings, which was still standing when the Arabs took the city in the VII century CE. We know also, according to Jewish and Christian texts, that most of the population of Vēh-Ardaxšīr was Christian or Jewish, and that the city was the see of a bishopric. In both cities, the majority of the population would have been formed by native Syriac speakers, with a small group of Iranian speakers forming the administrative, clerical and military elite.

Mesopotamia is flat, but that doesn’t mean that the environs of Ctesiphon were open terrain suited for army maneuvering. Apart from the large obstacle of the river Tigris, the terrain was crisscrossed by a dense network of irrigation canals, some of which (like the Naarmalcha canal) were large obstacles for troop movements (as François Paschoud showed in the paper I mentioned in the last chapter, due to hydraulic reasons and to the incline of the terrain, a major canal like the Naarmalcha must’ve had its water surface risen several meters above the surrounding terrain, and it was flanked by major earth dams). This would have been a problem for both armies; the Sasanian cavalry would’ve been denied the sort of open, flat terrain that its cavalry needed, but the Romans also found their advance encumbered by frequent ambushes and by floods caused by the Sasanian defenders who tried to delay their advance by opening locks and floodgates whenever possible. On top of it all, the whole area was densely settled and built up, and other than the “twin cities” there were multiple palaces, villages, country estates and smaller fortified towns and cities.

As I said in the previous chapter, there’s still a lack of understanding among scholars about the exact layout of the Naarmalcha, and this has been the cause for different interpretations of the arrival of the Roman army to Ctesiphon. Let’s see the different accounts by Ammianus, Zosimus, Libanius and we’ll also take a look at Cassius Dio’s account of Trajan’s campaign in 116-117 CE.

Ammianus Marcellinus (Res Gestae Libri XXXI, XXIV, 6, 1):

Zosimus (New History, III ,24, 2):

Libanius (Oration XVIII, 244-247)

Cassius Dio (Roman History, Book LXVIII, 28, 1-2)

If we take the three parallel narratives about this part of Julian’s expedition, Paschoud remarks that the less reliable one in this case is Ammianus, even if he accompanied it and was a direct eyewitness (let’s remember that he wrote his work almost thirty years later after he’d retired from the army and settled in Rome). For starters, a comparison with the other two accounts shows clearly that in this passage he’s confusing the Naarmalcha with the so-called “Canal of Trajan”. And on top of it, he’s obviously forgotten that he’d already written about the Naarmalcha in a previous passage (quoted in the previous chapter). Zosimus’ account is more precise, but it only specifies in a very indirect way that the Canal of Trajan was dry when Julian reached it. Of the three accounts, Libanius’ is the most helpful with geographical details in this case. In his account, he specifies that the Naarmalcha only reached the Tigris downstream from Seleucia (a deserted city by now) and Ctesiphon, but that another canal built by an ancient emperor (evidently, the Canal of Trajan) branched off from the Naarmalcha and reached the Tigris upstream from Ctesiphon.

Paschoud carries on with his study by pointing out that Cassius Dio’s text lets us know that the topography of the region had not changed much in two centuries, and that what IV century authors called “the Canal of Trajan” had not been made by that emperor. Dio’s passage has only arrived to us in an abbreviated form (through John Xiphilinus’ epitome) but it seems that Trajan did not seek to build a new canal, but that he merely repaired an existing one that was dry by then, as it happened again in 363 CE. Paschoud hypothesizes that this canal must’ve been much older, perhaps related to the foundation of the Hellenistic settlement of Seleucia on the Tigris; after the foundation of this city it would have become necessary to build a waterway that allowed shipping to reach its city docks without having to sail up the Tigris stream (the Naarmalcha reached the Tigris south of Seleucia’s location, same as with Ctesiphon and Vēh-Ardaxšīr).

Notice also how Dio’s text also show how the Romans were well aware of the difference in topographical levels between the Euphrates and Tigris. And two of the three narratives from the IV century attest to these effects: Ammianus describes that after reopening this blocked canal, it filled up quickly and the current was swift; Libanius also describes a brusque rise of the level of the waters of the Tigris between “Seleucia” (probably Vēh-Ardaxšīr) and Ctesiphon after Julian had this old canal repaired.

The Naarmalcha main role would have been as the principal irrigation canal in this region, and as irrigation was done by gravity, it was necessary for its water level to be higher than that of the surrounding land. The higher the level compared to that of its surrounding fields, the further the secondary irrigation channels that branched out could carry their water, and more land could be brought into cultivation. Today’s landscape in central and southern Iraq is thus still crisscrossed by these ancient canals (now dry) with their dams that lie well above the surrounding countryside; this practice was facilitated by the abundant amounts of alluvial sand and other deposits carried by the Euphrates, that meant that in its initial stages it was the water itself that brought the construction materials for the canals (although this also implied that later they would have needed constant dredging to keep their beds in working order).

Paschoud’s reconstruction (which I find personally convincing) goes against the reconstructions by Dodgeon & Lieu, as well as by Syvänne, according to whom the Roman supply fleet reached the Tigris directly through the Naarmalcha downstream of Ctesiphon, while Paschoud (reading correctly the ancient sources as we’ve seen above, especially Libanius) stated that the Roman fleet reached the Tigris via the so-called “Canal of Trajan” upstream of Ctesiphon. This will be important for later, when we will consider Julian’s decision to burn the fleet.

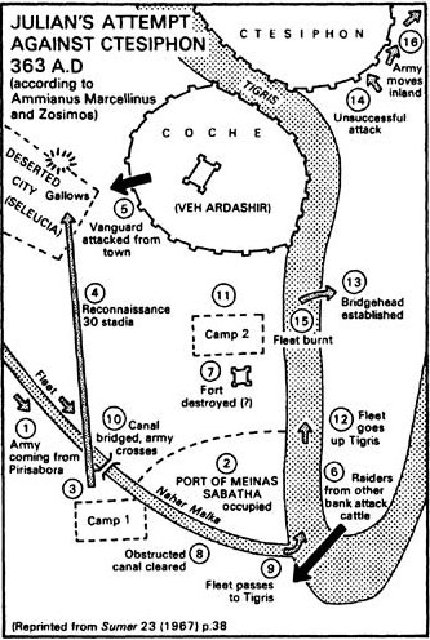

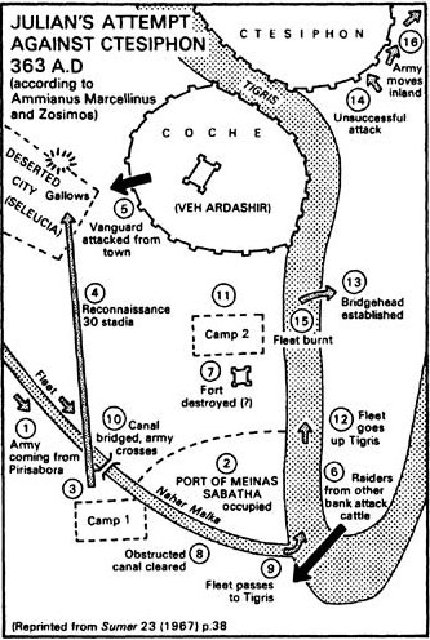

Julian’s attack on Ctesiphon according to Dodgeon & Lieu (from “The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (AD226–363): A Documentary History”)

The Romans came upon a palace built in Roman style and left it untouched (probably on 15 May), and they also found Šābuhr II’s hunt reserve well stocked with game (Ammianus XXIV, 5, 1–2, Zosimus III, 23, 1–2 and Libanius, orations XVII, 20 and XVIII, 243). At the site of the ruins of the ancient Hellenistic city of Seleucia (west of Vēh-Ardaxšīr, which was used by the Sasanian kings as a site for public executions, as stated in Christian Syriac martyrs’ acts) Julian saw the impaled bodies of the relatives of the Persian commander who surrendered Pērōz-Šābuhr (Ammianus XXIV, 5, 4). Here Nabdates, the former Persian commander of Maiozamalcha, who had surrendered to the Romans and was their prisoner but had “grown insolent”, was burnt alive with 80 of his men (Ammianus XXIV, 5, 4). A strong fortress nearby was captured by the Romans (probably on 16 May: Ammianus XXIV, 5, 6–11). This could be the Meinas Sabath (identified variously as either the Arsacid settlement of Vologesias/Walagašapat or as a suburb of Vēh-Ardaxšīr) mentioned in Zosimus III, 23, 3. The fleet then sailed down the Naarmalcha and the army reached the walls of Vēh-Ardaxšīr. (Ammianus XXIV, 6, 1–2, Zosimus III, 24, 2, Libanius, Oration XVIII, 245–7 and Malalas, XII, 10–16 -identical to Magnus of Carrhae’s Fragment 7).

This is a key moment in the narrative. Notice that according to some scholars (like Paschoud) the fleet reached the Tigris upstream from Ctesiphon / Vēh-Ardaxšīr (opening the locks of the so-called “Canal of Trajan”; hence the flooding in Vēh-Ardaxšīr recorded by Libanius) while according to others like Syvänne and Dodgeon & Lieu, the fleet reached the Tigris downstream from the twin cities.

This stucco panel (dated tentatively to the VI century CE) found near the great palace of Khusrō I in the Aspanbar area is thought to have belonged to the private palace of one of the high-ranking members o the Sasanian court. It’s one of the very few excavated artifacts from Sasanian Ctesiphon. Interiors of Sasanian palaces and temples were usually intricately covered with stucco decoration, which was later painted, either applied in situ or “prefabricated” and later fixed to the inner walls of the building (like this case). Two identical panels have been preserved, one in the Met in New York and the other at the Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin. According to Aboulala Soudavar, the Pahlavi inscription reads as “afzun” which can be translated into English as “to increase”, while the pearl roundel and the open wings are symbols for the ancient Iranian concept of “farr” (“divine” or “kingly” glory).

In his Oration V, the Christian author (contemporary of the events) Gregory of Nazianzus stated that both cities were “strongly defended”. As we’ve seen, archaeological digs in Vēh-Ardaxšīr confirm this, and the same is assumed to be true by scholars with respect to Ctesiphon on the other bank of the Tigris. The Babylonian Talmud also informs us that the civilians of Māhōzē were organized in a militia that was mobilized in case of a military emergency; so the Romans had to contend with two very large and populous cities that were very well fortified and defended, and which couldn’t be cut off from the outside world, unless they were both besieged at the same time (as they were united by bridges) and the besiegers cut the Tigris both upstream and upstream from the cities. And on top of it all, the Romans would have needed to do this without having defeated before the main Sasanian army led by the Šahān Šāh, which as we will see was about to arrive in scene. For the sake of comparison, in the VII century CE it took the Muslim Arab conquerors a year to besiege and conquer both cities, and only because they’d destroyed previously the main Sasanian field army at al-Qadisiyyah and a defected Sasanian engineer built eight catapults for them. Julian did not have that amount of time available, and probably he’d planned the invasion of Ērānšahr in the same way he’d planned his commando raids against the Franks and Alamanni in the Rhine. But this enemy was different.

Julian partially unloaded the fleet and used the boats to ferry soldiers across the Tigris against a strong Sasanian defense; a bitter battle was fought before the gates of Ctesiphon and won by the Romans, but (according to Ammianus) they were unable to exploit the victory because of a lack of discipline. Let’s see the different accounts:

Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae Libri XXXI, 6, 4-15:

Festus, Breviarium 28:

Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration V, 9-10:

Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical History, VI, 5-8:

Zosimus, New History, III, 24-25:

The accounts by Ammianus and Zosimus are the most complete ones, and they mostly agree on broad terms. What they describe is a bold crossing of the Tigris by the Roman army in successive assault waves against a Sasanian army massed on the opposite bank, and deployed in a classic Sasanian battle order: a first line formed by heavy cavalry (savārān) a second line of infantry massed in closed ranks and lastly a line of war elephants (presumably to act as regrouping points for the infantry if it was routed by the Romans, to cover a retreat if necessary and to offer a good shooting platform to Sasanian bowmen given the height advantage offered by these animals; and finally perhaps also to ensure the infantry kept up its fighting spirit, or else).

As it was a purely frontal battle without any possibility for maneuvering, this was the sort of combat in which the Roman infantry excelled, and it’s noteworthy that the Sasanian forces were able to put up such a long fight. Notice that this was still not Šābuhr II’s main army, but merely the cavalry screen of Sūrēn (one of the Sasanian commanders in the battle) alongside with local forces, probably drawn from the garrisons of the twin cities. Nothing is known about the other two Sasanian commanders, Pigranes (“Pigraxes” in Zosimus) and Narseus (“Anareus” in Zosimus; Middle Persian Narsē); who were perhaps the military governors (marzbānan) of the twin cities. This time, Julian’s audacity and boldness (and sheer luck) served him well, and his night amphibious assault was victorious, although his strategic situation had not improved in the slightest.

The British reenactor Nadeem Ahmad from the reenacting group “Eran ud Turan” in the full garb of a Sasanian spāhbed.

It’s now when Julian had to cope with the reality of his strategic position: he’d won several tactical victories but he still found himself in a position that could at the very best be described as a strategic stalemate, and which was bound to worsen with every passing day. The army encamped, but apparently Julian didn’t even consider seriously to start a formal siege of Ctesiphon, instead he took a decision that all the ancient sources criticize strongly, and which according to them was the reason for the final failure of the campaign. Some of the sources (mostly Christian ones) attribute it to Julian being fooled by a devious “Persian” trick (a common place when dealing with easterners in classical authors: they were deceitful, devious, etc.). According to Libanius (Oration XVIII, 257-259) and Socrates of Constantinople (Ecclesiastical History, III, 21, 4–8) Julian rejected peace overtures from Šābuhr II. Ammianus says nothing of the sort; he only wrote that a council of war was held (at a place called Abuzatha by Zosimus; scholars have been unable to find this location, judging from the context of the narrative, it must’ve been located east of Ctesiphon) and a decision to march inland was made (probably on 5 June). These are the sources:

Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae Libri XXXI, XXIV, 7, 1–3:

Zosimus: New History, III, 26, 1:

Libanius, Oration XVIII, 261:

Eunapius of Sardes, fragments 22.3 and 27:

John Zonaras, Extracts of History, XIII, 13, 10:

Notice that for the first time Ammianus mentions the fear that Šābuhr II was approaching with the main Sasanian army. At this moment, Julian took the controversial decision of burning his transport fleet (Dodgeon and Lieu date it to the timeframe between 11–15 June). These are the sources reporting on Julian’s decision:

Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae Libri XXXI, XXIV, 7, 3–5:

Zosimus: New History, III; 26, 2–3:

Libanius: Oration XVIII, 262–3:

Ephraim the Syrian: Hymns against Julian, III, 15:

Gregory of Nazianzus: Oration V, 11–12:

Sozomenus: Ecclesiastical History, VI, 1, 9:

Theodoret of Cyrrhus: Ecclesiastical History, III, 25, 1,

Festus: Breviarium 28:

John Zonaras: Extracts of History, XIII, 13, 2–9:

Some ancient sources put forward the theory that Julian was led astray by one or more Sasanian double agents (Gregory of Nazianzus, Ephraim the Syrian, Festus, Socrates of Constantinople, Sozomenus, Philostorgius, John Malalas, the anonymous Passion of Artemius, and John Zonaras). But in my opinion it’s unnecessary to resort to such novelesque tales to explain Julian’s decision. If he was marching “inland” and possibly along the Diyala River, the fleet would’ve been useless. But even in case of a retreat to the north, the fleet would’ve been mostly an encumbrance due to a simple reason: upstream from Ctesiphon (near present-day Baghdad), the topographical incline of the Tigris riverbed becomes too steep to allow navigation if it’s not with engine-propelled boats or by pulling the boats from the banks (as Libanius correctly stated). Considering that by now a good part of the supplies carried by the fleet would’ve been consumed anyway, at least part of the boats would’ve been empty and so pulling them would’ve been completely useless. And in the case that (as Syvänne and Dodgeon & Lieu assume), the Roman fleet had reached the Tigris downstream from Ctesiphon / Vēh-Ardaxšīr, pulling it past the twin cities would’ve been simply impossible. Still, as almost all the sources (even Ammianus, who was present there) sharply criticize Julian’s decision, it’s to be assumed that the fleet still carried supplies, that now would have to be carried by the pack animals of the army. It’s now when the reason for the attacks of Suren’s cavalry against the pack animals of the army and against its foraging parties became sharply evident: the army simply lacked enough pack animals to carry all the supplies. And possibly it would have also lacked enough of them to pull the fleet upstream, unless Julian used part of his manpower to pull the boats (indeed, both Ammianus and Libanius name this as the reason for Julian’s decision).

A second council of war was held (at Noorda according to Zosimus, perhaps modern Djsir Nahrawan near the

river Tamarra) and the decision to head for Corduene (roughly modern Iraqi Kurdistan) rather than to return via Āsūrestān was agreed upon (or imposed by Julian). The army struck camp on 16 June and marched due north towards the river Douros (considered by most scholars to be the Diyala River). Let’s see Ammianus’ account:

Ammianus Marcellinus (Res Gestae Libri XXXI, XXIV, 8, 2-6):

Notice the chronology, as reconstructed by Dodgeon & Lieu: the Roman army started its invasion (crossing of the Khabur river) on April 4, and the battle of Ctesiphon happened shortly after May 16. In a month and a half, the Roman army had conducted a “lightning” invasion, took two major fortified Sasanian towns/cities (Pērōz-Šābuhr and Maiozamalcha) and reached the enemy capital. But then, this rapid pace of events stagnates; by June 5 Julian decides to “march inland” and between June 11-15 the Roman fleet is burnt and the army departs the environs of Ctesiphon. It seems, according to Ammianus’ account (and the same is suggested by some of the other accounts too) that Julian and his generals really didn’t know what to do. Harrel proposed that Julian’s decision to follow the Diyala River upstream (if that’s in effect the Douros of the classical sources) was an attempt to invade the Iranian Plateau itself: the valley of this river is the main pass across the Zagros, and it leads directly to Ecbatana / Hamadān. This would be a move beyond rash even for a commander given to bold moves like Julian; and Harrel suggests that it was perhaps a way to try to force a decisive field battle against Šābuhr II’s main army. Syvänne, although very critical of Julian’s abilities as a commander, thinks that this was a move merely dictated by geography and that Julian intended indeed to retreat northwards as swiftly as possible. This is also perfectly reasonable: if we look at a map, we can see that the Diyala River joins the Tigris a few km. upstream from Ctesiphon, and so if the Roman army was retreating north along the eastern bank of the Tigris, it would need to find a bridge or a ford to cross it; that justifies perfectly following the river upstream until some crossing point was found.

The decision to retreat along the eastern bank of the Tigris is also a rational one and resorting to elaborate conspiracy theories is unnecessary to explain Julian’s decision. As Libanius points out, the route the army had followed from the Roman border couldn’t be followed now, as the invaders had destroyed all the fields and harvests. Upstream from Ctesiphon, the western bank of the Tigris is mostly barren land (steppe or desert) as it can’t be irrigated by gravity, but the eastern bank is crossed by several rivers that descend from the Zagros Mountains (the Diyala, the Greater Zab and the Little Zab) that allow for the existence of irrigated agriculture, and most importantly: its fields and orchards had not been devastated still by the invading army.

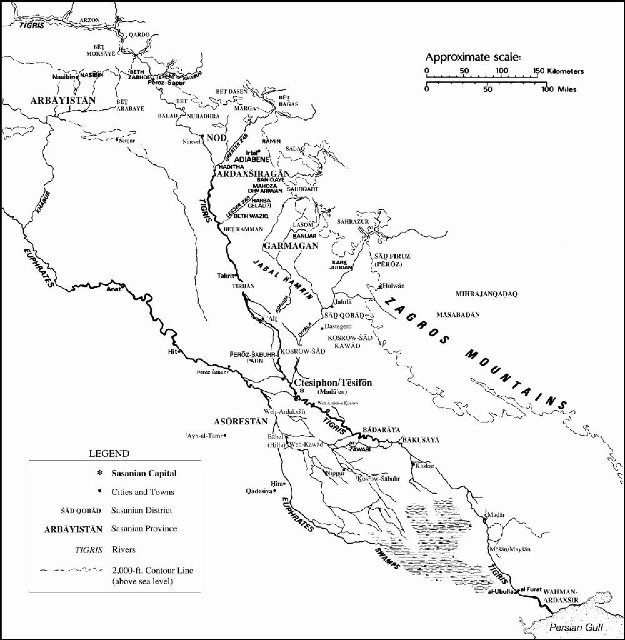

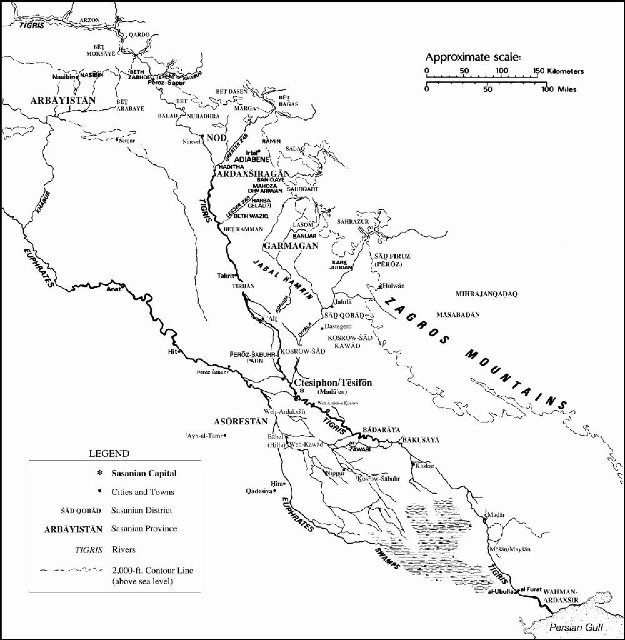

Map of Sasanian Mesopotamia. Notice the course of the Diyala River and its confluence with the Tigris upstream from Ctesiphon.

Another factor that could have influenced Julian’s decision is the possibility to join forces with the Roman army of Sebastianus and Procopius (which should’ve invaded Media or at least Adiabene / Nodšēragān but which had done nothing at all) or the Armenian army, which apparently had managed to invade Media; that could’ve been a factor in the initial march upstream the Diyala River towards Media (Chiliocomum was the classical name for the Nisaean Plain around Ecbatana / Hamadān). But, for one reason or another, neither of these armies joined forces with Julian.

And anyway, between Julian’s army and them (and a safe passage back towards Roman territory) now stood Šābuhr II with his main army, blocking his way.

After the fall of Maiozamalcha, the Roman army crossed a series of canals, and an attempt to stop them by the Sasanians was foiled (Ammianus XXIV, 4, 31). The relative ease with which the Roman army reached the outskirts of Ctesiphon is briefly mentioned in many other sources, like Libanius’ Epistle 1402, 2–3, Eutropius X, 16, 1; Festus, Breviarium, 28, p. 67. 18–19; Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration V,9; Socrates, III, 21, 3, Sozomenus VI, 1, 4, Malalas, XIII, pp. 329, 23–330 and Zonaras, XIII, 13, 1.

At this point, the Roman army reached the western bank of the Tigris, the location of the twin cities of Vēh-Ardaxšīr (called Coche or Kōḵē in Syriac Christian texts, or Māhōzē in the Babylonian Talmud, and still called anachronistically “Seleucia” by Greek and Latin authors like Libanius or Ammianus)on the western bank of the river and Ctesiphon (Middle Persian Ṭīsfūn) on its eastern bank. Ctesiphon has never been excavated, and Vēh-Ardaxšīr was only excavated briefly in the late 1920s by an American team and later in 1964 by an Italian one which managed to draw a map of the southwestern quarter of the city.

Reconstruction of the surroundings of Ctesiphon / Vēh-Ardaxšīr in Late Antiquity. The riverbed of the Tigris has changed significantly across the centuries. The westernmost course is the one that existed from the III century BCE to the I century CE, and as you can see, it reached the Hellenistic foundation of Seleucia; while Ctesiphon (founded by the Arsacids in the II century CE stood quite far removed on the eastern bank of the river. Vologesias / Walagašapat was founded by the Arsacid king Vologases I (Walagaš in Parthian, Walāxš in Middle Persian and Balāš in New Persian and Arabic) in he second half of the I century CE, probably after the Tigris changed course and left Seleucia without its river port. Vēh-Ardaxšīr was founded by the first Sasanian Šahān Šāh Ardaxšīr I in 230 CE just opposite the river from Ctesiphon, since then the Tigris has again changed course and now its riverbed crosses almost straight through the center of the ancient city. The irregular pink shape in the map is the excavated area of the old city, and the thick black line the part of the ancient wall that has been discovered (and which has led archaeologists to believe it was a “round city” as many other Arsacid and Sasanian foundations.

Based on the Italian excavations, Vēh-Ardaxšīr was a typical Sasanian city, built on a round plan and was heavily fortified, with circular walls studded with semicircular towers at regular intervals of 35 meters. The wall was very thick (10 meters wide at the foundations) and was protected by a wide moat, probably filled by water and built in mudbrick; all in all strikingly similar to the fortifications of better-known Central Asian cities that were also part of the Sasanian empire (permanently or temporarily) like Merv or Balḵ. From Christian and Jewish texts, we also know that the city had a citadel (known in Middle Persian as Grondagan or Garondagan, and as Aqra d’Kōḵē in Syriac) where the Sasanian governor, functionaries and garrison resided. The city lodged also one of the royal mints of the empire (Ctesiphon had another).

According to Tabarī, two bridges united Vēh-Ardaxšīr with Ctesiphon (one of them built by Šābuhr II early on his reign). Nothing is known for sure about Ctesiphon proper, as the German excavations before the WWI and the American ones in the 1920s only covered the Aspanbar area south of Ctesiphon proper, where in the VI century Khusrō I and his successors built the great palace of which still stands the throne hall, as well as pleasure gardens, walled hunting grounds, and where the members of the Sasanian court also built their private palaces near the royal residence. But all this did not exist yet in 363 CE, Ctesiphon proper is supposed to have been another walled city built on a round plan as was typical of Arsacid and Sasanian foundations, following the Central Asian custom. Inside the walls stood the “White Palace”, the palace of the Sasanian kings, which was still standing when the Arabs took the city in the VII century CE. We know also, according to Jewish and Christian texts, that most of the population of Vēh-Ardaxšīr was Christian or Jewish, and that the city was the see of a bishopric. In both cities, the majority of the population would have been formed by native Syriac speakers, with a small group of Iranian speakers forming the administrative, clerical and military elite.

Mesopotamia is flat, but that doesn’t mean that the environs of Ctesiphon were open terrain suited for army maneuvering. Apart from the large obstacle of the river Tigris, the terrain was crisscrossed by a dense network of irrigation canals, some of which (like the Naarmalcha canal) were large obstacles for troop movements (as François Paschoud showed in the paper I mentioned in the last chapter, due to hydraulic reasons and to the incline of the terrain, a major canal like the Naarmalcha must’ve had its water surface risen several meters above the surrounding terrain, and it was flanked by major earth dams). This would have been a problem for both armies; the Sasanian cavalry would’ve been denied the sort of open, flat terrain that its cavalry needed, but the Romans also found their advance encumbered by frequent ambushes and by floods caused by the Sasanian defenders who tried to delay their advance by opening locks and floodgates whenever possible. On top of it all, the whole area was densely settled and built up, and other than the “twin cities” there were multiple palaces, villages, country estates and smaller fortified towns and cities.

As I said in the previous chapter, there’s still a lack of understanding among scholars about the exact layout of the Naarmalcha, and this has been the cause for different interpretations of the arrival of the Roman army to Ctesiphon. Let’s see the different accounts by Ammianus, Zosimus, Libanius and we’ll also take a look at Cassius Dio’s account of Trajan’s campaign in 116-117 CE.

Ammianus Marcellinus (Res Gestae Libri XXXI, XXIV, 6, 1):

Then we came to an artificial river, by name Naarmalcha, meaning "the kings' river", which at that time was dried up. Here in days gone by Trajan, and after him Severus, had with immense effort caused the accumulated earth to be dug out, and had made a great canal, in order to let in the water from the Euphrates and give boats and ships access to the Tigris. It seemed to Julian in all respects safest to clean out the same canal, which formerly the Persians, when in fear of a similar invasion, had blocked with a huge dam of stones. As soon as the canal was cleared, the dams were swept away by the great flow of water, and the fleet in safety covered thirty stadia and was carried into the channel of the Tigris. Thereupon bridges were at once made, and the army crossed and pushed on towards Coche (i.e. Vēh-Ardaxšīr). Then, so that a timely rest might follow the wearisome toil, we encamped in a rich territory, abounding in orchards, vineyards, and green cypress groves. In its midst is a pleasant and shady dwelling, displaying in every part of the house, after the custom of that nation, paintings representing the king killing wild beasts in various kinds of hunting; for nothing in their country is painted or sculptured except slaughter in diverse forms and scenes of war.

Zosimus (New History, III ,24, 2):

They advanced to a very broad sluice or channel, said by the country people to have been cut by Trajan, when he made an expedition into Persia. In this channel runs the river Narmalaches and discharges itself into the Tigris. The emperor caused it to be cleansed, in order to enable his vessels to pass through it into the Tigris, and constructed bridges over it for the passage of his army.

Libanius (Oration XVIII, 244-247)

Doing things of this sort, they at length arrive at the cities, so long objects of their desire, the which, in place of Babylon, adorn the land of the Babylonians. Through the midst of these runs the river Tigris, and after passing by them some little distance, unites with the Euphrates. At this point, what was to be done could not be discovered; for if the soldiers should pass along in the flotilla it was impossible to approach the towns; whilst if they attacked the towns, their boats would be useless to them, and if they should sail up the Tigris, the labor would be excessive, and they would have to pass in the middle between the cities. Who then solved the difficulty? It was not a Calchas, nor a Tiresias, nor any one of the diviners; the emperor seized some prisoners out of those dwelling in the neighborhood, and made inquiry about a navigable canal (this too from his books) constructed by the ancient kings, and leading from the Tigris into the Euphrates, at some distance from the two cities (i.e. Ctesiphon and Vēh-Ardaxšīr). Of these prisoners, the youthfulness of the one was entirely unsuspicious of his design in putting the question, whilst the one of advanced age told the truth because there was no help for it (for he perceived that the emperor was as exactly informed about the locality as anyone of the natives, so much had he, though distant, got a view of the place in books). The elder prisoner therefore tells, both where the canal is, and in what way it is closed up, and that it had been filled up with earth, and sowed over with corn at the part next its opening. At the nod of the commander all the obstruction was taken out, and of the two streams the one is seen drained dry; the other bore along the flotilla which kept side by side with the army; whilst the Tigris coming down upon those in the cities greater than before, inasmuch as it had received the waters of the Euphrates, occasioned them great alarm, in the belief that it would not spare their walls.

Cassius Dio (Roman History, Book LXVIII, 28, 1-2)

Trajan had planned to conduct the Euphrates through a canal into the Tigris, in order that he might take his boats down by this route and use them to make a bridge. But learning that this river has a much higher elevation than the Tigris, he did not do so, fearing that the water might rush down in a flood and render the Euphrates unnavigable. So, he used hauling-engines to drag the boats across the very narrow space that separates the two rivers (the whole stream of the Euphrates empties into a marsh and from there somehow joins the Tigris); then he crossed the Tigris and entered Ctesiphon.

If we take the three parallel narratives about this part of Julian’s expedition, Paschoud remarks that the less reliable one in this case is Ammianus, even if he accompanied it and was a direct eyewitness (let’s remember that he wrote his work almost thirty years later after he’d retired from the army and settled in Rome). For starters, a comparison with the other two accounts shows clearly that in this passage he’s confusing the Naarmalcha with the so-called “Canal of Trajan”. And on top of it, he’s obviously forgotten that he’d already written about the Naarmalcha in a previous passage (quoted in the previous chapter). Zosimus’ account is more precise, but it only specifies in a very indirect way that the Canal of Trajan was dry when Julian reached it. Of the three accounts, Libanius’ is the most helpful with geographical details in this case. In his account, he specifies that the Naarmalcha only reached the Tigris downstream from Seleucia (a deserted city by now) and Ctesiphon, but that another canal built by an ancient emperor (evidently, the Canal of Trajan) branched off from the Naarmalcha and reached the Tigris upstream from Ctesiphon.

Paschoud carries on with his study by pointing out that Cassius Dio’s text lets us know that the topography of the region had not changed much in two centuries, and that what IV century authors called “the Canal of Trajan” had not been made by that emperor. Dio’s passage has only arrived to us in an abbreviated form (through John Xiphilinus’ epitome) but it seems that Trajan did not seek to build a new canal, but that he merely repaired an existing one that was dry by then, as it happened again in 363 CE. Paschoud hypothesizes that this canal must’ve been much older, perhaps related to the foundation of the Hellenistic settlement of Seleucia on the Tigris; after the foundation of this city it would have become necessary to build a waterway that allowed shipping to reach its city docks without having to sail up the Tigris stream (the Naarmalcha reached the Tigris south of Seleucia’s location, same as with Ctesiphon and Vēh-Ardaxšīr).

Notice also how Dio’s text also show how the Romans were well aware of the difference in topographical levels between the Euphrates and Tigris. And two of the three narratives from the IV century attest to these effects: Ammianus describes that after reopening this blocked canal, it filled up quickly and the current was swift; Libanius also describes a brusque rise of the level of the waters of the Tigris between “Seleucia” (probably Vēh-Ardaxšīr) and Ctesiphon after Julian had this old canal repaired.

The Naarmalcha main role would have been as the principal irrigation canal in this region, and as irrigation was done by gravity, it was necessary for its water level to be higher than that of the surrounding land. The higher the level compared to that of its surrounding fields, the further the secondary irrigation channels that branched out could carry their water, and more land could be brought into cultivation. Today’s landscape in central and southern Iraq is thus still crisscrossed by these ancient canals (now dry) with their dams that lie well above the surrounding countryside; this practice was facilitated by the abundant amounts of alluvial sand and other deposits carried by the Euphrates, that meant that in its initial stages it was the water itself that brought the construction materials for the canals (although this also implied that later they would have needed constant dredging to keep their beds in working order).

Paschoud’s reconstruction (which I find personally convincing) goes against the reconstructions by Dodgeon & Lieu, as well as by Syvänne, according to whom the Roman supply fleet reached the Tigris directly through the Naarmalcha downstream of Ctesiphon, while Paschoud (reading correctly the ancient sources as we’ve seen above, especially Libanius) stated that the Roman fleet reached the Tigris via the so-called “Canal of Trajan” upstream of Ctesiphon. This will be important for later, when we will consider Julian’s decision to burn the fleet.

Julian’s attack on Ctesiphon according to Dodgeon & Lieu (from “The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (AD226–363): A Documentary History”)

The Romans came upon a palace built in Roman style and left it untouched (probably on 15 May), and they also found Šābuhr II’s hunt reserve well stocked with game (Ammianus XXIV, 5, 1–2, Zosimus III, 23, 1–2 and Libanius, orations XVII, 20 and XVIII, 243). At the site of the ruins of the ancient Hellenistic city of Seleucia (west of Vēh-Ardaxšīr, which was used by the Sasanian kings as a site for public executions, as stated in Christian Syriac martyrs’ acts) Julian saw the impaled bodies of the relatives of the Persian commander who surrendered Pērōz-Šābuhr (Ammianus XXIV, 5, 4). Here Nabdates, the former Persian commander of Maiozamalcha, who had surrendered to the Romans and was their prisoner but had “grown insolent”, was burnt alive with 80 of his men (Ammianus XXIV, 5, 4). A strong fortress nearby was captured by the Romans (probably on 16 May: Ammianus XXIV, 5, 6–11). This could be the Meinas Sabath (identified variously as either the Arsacid settlement of Vologesias/Walagašapat or as a suburb of Vēh-Ardaxšīr) mentioned in Zosimus III, 23, 3. The fleet then sailed down the Naarmalcha and the army reached the walls of Vēh-Ardaxšīr. (Ammianus XXIV, 6, 1–2, Zosimus III, 24, 2, Libanius, Oration XVIII, 245–7 and Malalas, XII, 10–16 -identical to Magnus of Carrhae’s Fragment 7).

This is a key moment in the narrative. Notice that according to some scholars (like Paschoud) the fleet reached the Tigris upstream from Ctesiphon / Vēh-Ardaxšīr (opening the locks of the so-called “Canal of Trajan”; hence the flooding in Vēh-Ardaxšīr recorded by Libanius) while according to others like Syvänne and Dodgeon & Lieu, the fleet reached the Tigris downstream from the twin cities.

This stucco panel (dated tentatively to the VI century CE) found near the great palace of Khusrō I in the Aspanbar area is thought to have belonged to the private palace of one of the high-ranking members o the Sasanian court. It’s one of the very few excavated artifacts from Sasanian Ctesiphon. Interiors of Sasanian palaces and temples were usually intricately covered with stucco decoration, which was later painted, either applied in situ or “prefabricated” and later fixed to the inner walls of the building (like this case). Two identical panels have been preserved, one in the Met in New York and the other at the Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin. According to Aboulala Soudavar, the Pahlavi inscription reads as “afzun” which can be translated into English as “to increase”, while the pearl roundel and the open wings are symbols for the ancient Iranian concept of “farr” (“divine” or “kingly” glory).

In his Oration V, the Christian author (contemporary of the events) Gregory of Nazianzus stated that both cities were “strongly defended”. As we’ve seen, archaeological digs in Vēh-Ardaxšīr confirm this, and the same is assumed to be true by scholars with respect to Ctesiphon on the other bank of the Tigris. The Babylonian Talmud also informs us that the civilians of Māhōzē were organized in a militia that was mobilized in case of a military emergency; so the Romans had to contend with two very large and populous cities that were very well fortified and defended, and which couldn’t be cut off from the outside world, unless they were both besieged at the same time (as they were united by bridges) and the besiegers cut the Tigris both upstream and upstream from the cities. And on top of it all, the Romans would have needed to do this without having defeated before the main Sasanian army led by the Šahān Šāh, which as we will see was about to arrive in scene. For the sake of comparison, in the VII century CE it took the Muslim Arab conquerors a year to besiege and conquer both cities, and only because they’d destroyed previously the main Sasanian field army at al-Qadisiyyah and a defected Sasanian engineer built eight catapults for them. Julian did not have that amount of time available, and probably he’d planned the invasion of Ērānšahr in the same way he’d planned his commando raids against the Franks and Alamanni in the Rhine. But this enemy was different.

Julian partially unloaded the fleet and used the boats to ferry soldiers across the Tigris against a strong Sasanian defense; a bitter battle was fought before the gates of Ctesiphon and won by the Romans, but (according to Ammianus) they were unable to exploit the victory because of a lack of discipline. Let’s see the different accounts:

Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae Libri XXXI, 6, 4-15:

Since thus far everything had resulted as he desired, the Augustus now with greater confidence strode on to meet all dangers, hoping for so much from a fortune which had never failed him that he often dared many enterprises bordering upon rashness. He unloaded the stronger ships of those which carried provisions and artillery, and manned them each with eight hundred armed soldiers; then keeping by him the stronger part of the fleet, which he had formed into three divisions, in the first quiet of night he sent one part under comes Victor with orders speedily to cross the river and take possession of the enemy's side of the stream. His generals in great alarm with unanimous entreaties tried to prevent him from taking this step but could not shake the emperor's determination. The flag was raised according to his orders, and five ships immediately vanished from sight. But no sooner had they reached the opposite bank than they were assailed so persistently with firebrands and every kind of inflammable material, that ships and soldiers would have been consumed, had not the emperor, carried away by the keen vigor of his spirit, cried out that our soldiers had, as directed, raised the signal that they were already in possession of the shore, and ordered the entire fleet to hasten to the spot with all the speed of their oars. The result was that the ships were saved uninjured, and the surviving soldiers, although assailed from above with stones and every kind of missiles, after a fierce struggle scaled the high, precipitous banks and held their positions unyieldingly. History acclaims Sertorius for swimming across the Rhine with arms and cuirass; but on this occasion some panic-stricken soldiers, fearing to remain behind after the signal had been given, lying on their shields, which are broad and curved, and clinging fast to them, though they showed little skill in guiding them, kept up with the swift ships across the eddying stream.

The Persians opposed to us serried bands of mail-called horsemen in such close order that the gleam of moving bodies covered with densely fitting plates of iron dazzled the eyes of those who looked upon them, while the whole throng of horse was protected by coverings of leather. The cavalry was backed up by companies of infantry, who, protected by oblong, curved shields covered with wickerwork and raw hides, advanced in very close order. Behind these were elephants, looking like walking hills, and, by the movements of their enormous bodies, they threatened destruction to all who came near them, dreaded as they were from past experience.

Hereupon the emperor, following Homeric tactics, filled the space between the lines with the weakest of the infantry, fearing that if they formed part of the van and shamefully gave way, they might carry off all the rest with them; or if they were posted in the rear behind all the centuries, they might run off at will with no one to check them. He himself with the light-armed auxiliaries hastened now to the front, and now to the rear.

So, when both sides were near enough to look each other in the face, the Romans, gleaming in their crested helmets and swinging their shields as if to the rhythm of the anapaestic foot, advanced slowly; and the light-armed skirmishers opened the battle by hurling their javelins, while the earth everywhere was turned to dust by both sides and swept away in a swift whirlwind. And when the battle-cry was raised in the usual manner by both sides and the trumpets' blare increased the ardor of the men, here and there they fought hand-to‑hand with spears and drawn swords; and the soldiers were freer from the danger of the arrows the more quickly they forced their way into the enemy's ranks. Meanwhile Julian was busily engaged in giving support to those who gave way and in spurring on the laggards, playing the part both of a valiant fellow-soldier and of a commander. Finally, the first battle-line of the Persians began to waver, and at first slowly, then at quick step, turned back and made for the neighboring city with their armor well heated up. Our soldiers pursued them, wearied though they also were after fighting on the scorching plains from sunrise to the end of the day, and following close at their heels and hacking at their legs and backs, drove the whole force with Pigranes, the Surena, and Narseus, their most distinguished generals, in headlong flight to the very walls of Ctesiphon. And they would have pressed in through the gates of the city, mingled with the throng of fugitives, had not the general called Victor, who had himself received a flesh-wound in the shoulder from an arrow, raising his hand and shouting, restrained them; for he feared that the excited soldiers, if they rashly entered the circuit of the walls and could find no way out, might be overcome by weight of numbers (…).

After their fear was past, trampling on the overthrown bodies of their foes, our soldiers, still dripping with blood righteously shed, gathered at their emperor's tent, rendering him praise and thanks because he had won so glorious a victory, everywhere without recognition whether he was leader or soldier, and considering the welfare of others rather than his own. For as many as 2,500 Persians had been slain, with the loss of only seventy of our men. Julian addressed many of them by name, whose heroic deeds performed with unshaken courage he himself had witnessed, and rewarded them with naval, civic, and camp crowns.

Festus, Breviarium 28:

Having pitched his camp opposite to Ctesiphon on the bank where the Tigris joins the Euphrates, he spent the day in athletic contests to relieve the enemy of their watchfulness. In the middle of the night he embarked his soldiers and suddenly carried them across to the far bank. They struggled over the escarpment, where the ascent would have been difficult even in daytime when no one was trying to stop them. They threw the Persians into confusion by the unexpected terror and the armies of their entire nation were turned to flight. The soldiers would have victoriously entered the open gates of Ctesiphon if the opportunity for booty had not been greater than their concern for victory.

Gregory of Nazianzus, Oration V, 9-10:

Now, the first steps in his (i.e. Julian’s) enterprise, excessively audacious and much celebrated by those of his own party, were as follows. The entire region of Assyria that the Euphrates flows through, and skirting Persia, there unites itself with the Tigris; all this he took and ravaged, and captured some of the fortified towns, in the total absence of anyone to hinder him, whether he had taken the Persians unawares by the rapidity of his advance, or whether he was outgeneraled by them and drawn on by degrees further and further into the snare (for both stories are told); at any rate, advancing in this way, with his army marching along the river’s bank and his flotilla upon the river supplying provisions and carrying the baggage, after a considerable interval he reached Ctesiphon, a place which, even to be near, was thought by him half the victory, by reason of his longing for it.

From this point, however, like sand slipping from beneath the feet, or a great storm bursting upon a ship, things began to go black for him; for Ctesiphon is a strongly fortified town, hard to take, and very well secured by a wall of burnt brick, a deep ditch, and the swamps coming from the river. It is rendered yet more secure by another strong place, the name of which is Coche, furnished with equal defenses as far as regards garrison and artificial protection, so closely united with it that they appeared to be one city, the river separating both between them. For it was neither possible to take the place by general assault, nor to reduce it by siege, nor even to force a way through by means of the fleet principally, for he would run the risk of destruction; being exposed to missiles from higher ground on both sides, he left the place in his rear, and did so in this manner. He diverted a not inconsiderable part of the river Euphrates, the greatest of rivers, and rendered it navigable for vessels, by means of a canal, of which ancient vestiges are said to be visible; and thus joining the Tigris a little in front of Ctesiphon, he saved his boats from one river by means of the other river, in all security; in this way he escaped the danger that menaced him from the two garrisons. But, as he advanced, a Persian army suddenly started up, and continually received fresh reinforcements, but did not think it advisable to stand in front and fight it out, without the greatest necessity (although it was in their power to conquer, from their superior numbers); but from the tops of the hills and narrow passes they shot arrows and threw darts, whenever opportunity served, and thus readily prevented his further progress. Hence he is reduced to great perplexity, and, not knowing to what side to turn, he finds out an unlucky solution for the difficulty.

Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical History, VI, 5-8:

As he was journeying up the Euphrates, he arrived at Ctesiphon, a very large city, whither the Persian monarchs had now transferred their residence from Babylon. The Tigris flows near this spot. As he was prevented from reaching the city with his ships, by a part of the land which separated it from the river, he judged that either he must pursue his journey by water, or quit his ships and go to Ctesiphon by land; and he interrogated the prisoners on the subject. Having ascertained from them that there was a canal which had been blocked up in the course of time, he caused it to be cleared out, and, having thus effected a communication between the Euphrates and the Tigris, he proceeded towards the city, his ships floating along by the side of his army. But the Persians appeared on the banks of the Tigris with a formidable display of horse and many armed troops, of elephants, and of horses; and Julian became conscious that his army was besieged between two great rivers, and was in danger of perishing, either by remaining in its present position, or by retreating through the cities and villages which he had so utterly devastated that no provisions were obtainable; therefore he summoned the soldiers to see horse-races, and proposed rewards to the fleetest racers. In the meantime he commanded the officers of the ships to throw over the provisions and baggage of the army, so that the soldiers, I suppose, seeing themselves in danger by the lack of necessary provisions, might turn about boldly and fight their enemies more desperately. After supper he sent for the generals and tribunes and commanded the embarkation of the troops. They sailed along the Tigris during the night and came at once to the opposite banks and disembarked; but their departure was perceived by some of the Persians, who defended themselves and encouraged one another, but those still asleep the Romans readily overcame. At daybreak, the two armies engaged in battle; and after much bloodshed on both sides, the Romans returned by the river, and encamped near Ctesiphon.

Zosimus, New History, III, 24-25:

Soon after his execution, the army marched to Arintheus, and searching all the marshes found in them many people whom they made prisoners. Here it was that the Persians first collected their forces and attacked the advanced party of the Roman army. They were however routed and preserved their lives by flying to a neighboring city. The Persians on the other side of the river attacked the slaves who had the care of the beasts of burden, and those who guarded them; they killed part of them and made the rest prisoners. This being the first loss which the Romans had sustained occasioned some consternation in the army.

They advanced to a very broad sluice or channel, said by the country people to have been cut by Trajan, when he made an expedition into Persia. In this channel runs the river Narmalaches and discharges itself into the Tigris. The emperor caused it to be cleansed, in order to enable his vessels to pass through it into the Tigris, and constructed bridges over it for the passage of his army.

While this was in agitation, a great force of Persians, both horse and foot, was collected on the opposite bank, to prevent their passage should it be attempted. The emperor, discerning these preparations of the enemy, was anxious to cross over to them, and hastily commanded his troops to go on board the vessels.

Perceiving, however, the opposite bank to be unusually lofty, and a kind of fence at the top of it, which formerly served as an enclosure to the king's garden, but at this time was a rampart, they exclaimed that they were afraid of the fire-balls and darts that were thrown down. The emperor, however, being very resolute, two barges crossed over full of foot soldiers, which the Persians immediately set on fire by throwing down on them a great number of flaming darts.

This so increased the terror of the army, that the emperor was obliged to conceal his error by a feint, saying, "They are landed and have rendered themselves masters of the bank. I know it by the fire in their ships, which I ordered them to make as a signal of victory."

He had no sooner said this, than without further preparations they embarked in the ships and crossed over, until they arrived where they could ford the river, and then leaping into the water, they engaged the Persians so fiercely, that they not only gained possession of the bank, but recovered the two ships which came over first, and were now half burnt, and saved all the men who were left in them.

The armies then attacked each other with such fury, that the battle continued from midnight to noon of the next day. The Persians at length gave way, and fled with all the speed they could use, their commanders being the first who began to fly. Those were Pigraxes, a person of the highest birth and rank next to the king, Anareus, and Surena.

The Romans and Goths pursued them, and killed a great number, from whom they took a vast quantity of gold and silver, besides ornaments of all kinds for men and horses, with silver beds and tables, and whatever was left by the officers on the ramparts.

It is computed, that in this battle there fell of the Persians two thousand five hundred, and of the Romans not more than seventy-five. The joy of the army for this victory was lessened by Victor having received a wound from an engine.

The accounts by Ammianus and Zosimus are the most complete ones, and they mostly agree on broad terms. What they describe is a bold crossing of the Tigris by the Roman army in successive assault waves against a Sasanian army massed on the opposite bank, and deployed in a classic Sasanian battle order: a first line formed by heavy cavalry (savārān) a second line of infantry massed in closed ranks and lastly a line of war elephants (presumably to act as regrouping points for the infantry if it was routed by the Romans, to cover a retreat if necessary and to offer a good shooting platform to Sasanian bowmen given the height advantage offered by these animals; and finally perhaps also to ensure the infantry kept up its fighting spirit, or else).

As it was a purely frontal battle without any possibility for maneuvering, this was the sort of combat in which the Roman infantry excelled, and it’s noteworthy that the Sasanian forces were able to put up such a long fight. Notice that this was still not Šābuhr II’s main army, but merely the cavalry screen of Sūrēn (one of the Sasanian commanders in the battle) alongside with local forces, probably drawn from the garrisons of the twin cities. Nothing is known about the other two Sasanian commanders, Pigranes (“Pigraxes” in Zosimus) and Narseus (“Anareus” in Zosimus; Middle Persian Narsē); who were perhaps the military governors (marzbānan) of the twin cities. This time, Julian’s audacity and boldness (and sheer luck) served him well, and his night amphibious assault was victorious, although his strategic situation had not improved in the slightest.

The British reenactor Nadeem Ahmad from the reenacting group “Eran ud Turan” in the full garb of a Sasanian spāhbed.

It’s now when Julian had to cope with the reality of his strategic position: he’d won several tactical victories but he still found himself in a position that could at the very best be described as a strategic stalemate, and which was bound to worsen with every passing day. The army encamped, but apparently Julian didn’t even consider seriously to start a formal siege of Ctesiphon, instead he took a decision that all the ancient sources criticize strongly, and which according to them was the reason for the final failure of the campaign. Some of the sources (mostly Christian ones) attribute it to Julian being fooled by a devious “Persian” trick (a common place when dealing with easterners in classical authors: they were deceitful, devious, etc.). According to Libanius (Oration XVIII, 257-259) and Socrates of Constantinople (Ecclesiastical History, III, 21, 4–8) Julian rejected peace overtures from Šābuhr II. Ammianus says nothing of the sort; he only wrote that a council of war was held (at a place called Abuzatha by Zosimus; scholars have been unable to find this location, judging from the context of the narrative, it must’ve been located east of Ctesiphon) and a decision to march inland was made (probably on 5 June). These are the sources:

Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae Libri XXXI, XXIV, 7, 1–3:

Having held council with his most distinguished generals about the siege of Ctesiphon, the opinion of some was adopted, who felt sure that the undertaking was rash and untimely, since the city, impregnable by its situation alone, was well defended; and, besides, it was believed that the king would soon appear with a formidable force. So the better opinion prevailed, and the most careful of emperors, recognizing its advantage, sent Arintheus with a band of light-armed infantry, to lay waste the surrounding country, which was rich in herds and crops; Arintheus was also bidden, with equal energy to pursue the enemy, who had been lately scattered and concealed by impenetrable by-paths and their familiar hiding-places. But Julian, ever driven on by his eager ambitions, made light of words of warning, and upbraiding his generals for urging him through cowardice and love of ease to lose his hold on the Persian kingdom, which he had already all but won; with the river on his left and with ill-omened guides leading the way, resolved to march rapidly into the interior.

Zosimus: New History, III, 26, 1:

Upon the following day the emperor sent his army over the Tigris without difficulty, and the third day after the action he himself with his guards followed them. Arriving at a place by the Persians termed Abuzatha, he halted there five days.

Libanius, Oration XVIII, 261:

Nevertheless, this man (i.e. Julian) though invited to peace, went up to the walls (of Ctesiphon) and challenged the besieged to battle, saying that what they were doing was fit for women, but what they shunned for men. On their replying that he must seek out the king, and show himself to him, he was anxious to see and pass through Arbela, either without a battle, or after fighting a battle; so that in company with Alexander's victory at that place his own might become the theme of song. His intention was to traverse all the land which the Persian empire comprises; even more, the adjacent regions also; but he retreated because no reinforcements came to him, neither of his own side, nor from his ally: the latter through the false play of the prince of that nation; whilst the second army, according to report, because some of their men had been shot at the very beginning whilst bathing in the Tigris, had thought it better worth their while to wage war on the natives. Add to this, the quarrelling of the generals with one another had bred cowardice in those under their command; for whenever the one leader was gaining victories, the other, by recommending inaction, gave advice that pleased his men.

This state of things, however, did not discourage the emperor; he did not approve of their being absent, yet he proceeded as he had planned to do if they had joined him, and extended his views as far as Hyrcania and the rivers of India.

Eunapius of Sardes, fragments 22.3 and 27:

(He says) that the war against the Persians reached its peak under Julian and that either by invoking the gods or by calculation he comprehended from afar the disturbances of the Scythians, like waves on a smooth sea. Thereupon he says to someone in a letter, ‘The Scythians are now lying quiet, equally, they will not do so in the future’. His forethought for the future extended over such a period that he knew in advance that they would remain

quiet only for his own time.

(He says) that Julian, having previously revealed the plain before Ctesiphon as an orchestra for war, as Epaminondas said, now paraded it as a stage for Dionysus, providing relaxation and amusement for the troops.

(He says) that there was such an abundance of the provisions in the suburbs of Ctesiphon that the overriding danger faced by the troops was that of being destroyed by luxury.

(He says) that mankind, besides, seems generally inclined towards and readily given over to envy. And since the troops have no means of taking sides fairly about what is done, “From the tower”, they say, “they judged the Achaeans”, each one of them desirous of being versed in military matters and possessed of more than usual good sense. To some, then, any matter was the subject of foolishness, but he who followed the arguments right from the beginning went back to his own domain (…).

There is an oracle which was given to him while he was waiting at Ctesiphon: Zeus, the all-wise, once destroyed a race of Earth-born giants most hateful to the blessed ones who dwell in the Olympian halls. Julian the godlike, Emperor of the Romans, contending for the cities and long walls of the Persians, fighting hand-to-hand, destroyed them with fire and the valiant sword, subdued without pause their cities and many races. Seizing also, with heavy fighting, the German soil of those people of the west he laid waste their land.

John Zonaras, Extracts of History, XIII, 13, 10:

Some, therefore, say that Julian was deceived in this way. Others say he gave up the siege of Ctesiphon because of its strength and, since the army was running out of necessities, he considered returning (…)

Notice that for the first time Ammianus mentions the fear that Šābuhr II was approaching with the main Sasanian army. At this moment, Julian took the controversial decision of burning his transport fleet (Dodgeon and Lieu date it to the timeframe between 11–15 June). These are the sources reporting on Julian’s decision:

Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae Libri XXXI, XXIV, 7, 3–5:

But Julian, ever driven on by his eager ambitions, made light of words of warning, and upbraiding his generals for urging him through cowardice and love of ease to lose his hold on the Persian kingdom, which he had already all but won; with the river on his left and with ill-omened guides leading the way, resolved to march rapidly into the interior. And it seemed as if Bellona herself lighted the fire with fatal torch, when he gave orders that all the ships should be burned, with the exception of twelve of the smaller ones, which he decided to transport on wagons as helpful for making bridges. And he thought that this plan had the advantage that the fleet, if abandoned, could not be used by the enemy, or at any rate, that nearly 20,000 soldiers would not be employed in transporting and guiding the ships, as had been the case since the beginning of the campaign.

Zosimus: New History, III; 26, 2–3:

Meanwhile he consulted about his journey forward and found that it was better to march further into the country than to lead his army by the side of the river. There being now no necessity to proceed by water. Having considered this, he imparted it to his army, whom he commanded to burn the ships, which accordingly were all consumed, except eighteen Roman and four Persian vessels, which were carried along in wagons, to be used upon occasion. Their route now lying a little above the river, when they arrived at a place called Noorda they halted, and there killed and took a great number of Persians.

Libanius: Oration XVIII, 262–3:

But when the army was already on the move in that direction, and part was actually marching off, the other part collecting the baggage, some god diverts him from his first scheme, and, as the poet hath it, "warned him to think of his return." The flotilla, according to his original design, had been given for prey to the flames; for better so than to the enemy. The same thing would probably have been done, even though the former plan (of advancing) had never been contemplated; but that of returning had carried the day; because the Tigris, swift and strong, running counter to the prows of the boats, forced them to require a vast number of hands (to tow them up the stream); and it was necessary for those engaged in towing to be more than half the army; this meant that the fighting men were to be beaten, and after them everything else was gained by the enemy without fighting for it. Besides all this, the burning of the fleet removed every encouragement to laziness, for whoever wished to do nothing, by feigning sickness obtained conveyance in a boat; but when there were no vessels, every man was under arms. Since therefore it was impossible, however much they wished it, to keep so many vessels, it was decided not to be expedient even to retain those that had been saved (they were fifteen in number, reserved for making bridges); for the stream being too violent for the skill of the boatmen, and the multitude of hands, used to carry the boat with those embarked therein into the hands of the enemy; so that if it behooves the side that is injured to complain of the conflagration, it will be the Persian that has to grumble; and full often, they say, he did complain.

Ephraim the Syrian: Hymns against Julian, III, 15:

The king saw that the sons of the East had come and deceived

him,

the unlearned (had deceived) the wise man, the simple the

soohsayer.

They whom he had called, wrapped up in his robe,

had, through unlearned men, mastered his wisdom.

He commanded and burned his victorious ships,

and his idols and diviners were bound through the one deceit.

Gregory of Nazianzus: Oration V, 11–12:

A Persian of considerable standing, following the example of that Zopyrus employed by Cyrus in the case of Babylon, then pretended that he had had some quarrel, or rather a very great one and for a very great cause, with his king, and was on that account very hostile to the Persian cause, and well-disposed towards the Romans. He gained the emperor’s confidence through his pretense as follows: “Your Highness, what means all this, why are there so many shortcomings in so important an enterprise? What need is there of this provision fleet, this superfluous burden; a mere incentive to cowardice; for nothing is so unfit for fighting, and fond of laziness, as a full belly, and the having the means of saving oneself in one’s own hands? But if you will listen to me, you will burn this flotilla: what a relief to this fine army will be the result! You yourself will take another route, better supplied and safer than this; along which I will be your guide (being acquainted with the country as well as any man living), and will cause you to enter into the heart of the enemy’s country, where you can obtain whatever you please, and so make your way home; and me you shall then recompense, when you have actually ascertained my good will and sound advice”.

And when he had said this and gained credence to his story (for rashness is credulous, especially when God goads it on), everything went wrong at once. The boats became the prey of the flames. They were low on victuals.

Everywhere there was ridicule, and the whole venture resembled a suicide attempt. Hope vanished when the guide disappeared along with his promises. They were surrounded by the enemy and battle waged on all sides. It was difficult to advance and provisions were not easy to procure. In despair, the army became disenchanted with their commander. There was no hope for safety left, but one wish alone, as was natural under the circumstances, the ridding themselves of bad government and bad generalship.

Sozomenus: Ecclesiastical History, VI, 1, 9:

The emperor, being no longer desirous of proceeding further but wishing only to return to the (i.e. Roman) empire, burnt his vessels, as he considered that they required too many soldiers to guard them; and he then commenced his retreat along the Tigris, which was to his left. The prisoners, who acted as guides to the Romans, led them to a fertile country where at first they found an abundance of provisions.

Theodoret of Cyrrhus: Ecclesiastical History, III, 25, 1,

Julian’s folly was yet more clearly manifested by his death. He crossed the river that separates the Roman Empire from the Persian, brought over his army, and then forthwith burnt his boats, so making his men fight not in willing, but in forced obedience.

Festus: Breviarium 28:

After winning such great glory, when he received a warning from his retinue concerning the return, he put greater trust in his own purpose and burnt his fleet. He was misled by a deserter who had surrendered for the purpose of leading him astray and was induced to follow a direct route to Madaeana (perhaps Media?).

John Zonaras: Extracts of History, XIII, 13, 2–9:

Then suddenly affairs turned to the worse for him and he and the majority of his army perished. For the Persians in despair decided to rush headlong into destruction in order to do something really terrible to the Romans. Therefore, two men in the guise of deserters hurried to the Emperor and promised him victory over the Persians if he followed them. They advised him to leave the river and burn the galleys he had brought along with the other cargo vessels, so that the enemy could not use them, while they would lead his army to safety through a different way. It would quickly and safely reach the inner parts of Persia and conquer it with ease. The wicked man in his derangement believed them although many told him, and even Hormisdas himself, that it was a trap. But he set fire to his ships and burnt them all except twelve. There were seven hundred galleys and four hundred cargo vessels. After they had been completely burnt, when many of the tribunes objected that what was said by the deserters was a trap and a trick, he reluctantly agreed to examine the false deserters. Questioned under torture, they disclosed their conspiracy.

Some ancient sources put forward the theory that Julian was led astray by one or more Sasanian double agents (Gregory of Nazianzus, Ephraim the Syrian, Festus, Socrates of Constantinople, Sozomenus, Philostorgius, John Malalas, the anonymous Passion of Artemius, and John Zonaras). But in my opinion it’s unnecessary to resort to such novelesque tales to explain Julian’s decision. If he was marching “inland” and possibly along the Diyala River, the fleet would’ve been useless. But even in case of a retreat to the north, the fleet would’ve been mostly an encumbrance due to a simple reason: upstream from Ctesiphon (near present-day Baghdad), the topographical incline of the Tigris riverbed becomes too steep to allow navigation if it’s not with engine-propelled boats or by pulling the boats from the banks (as Libanius correctly stated). Considering that by now a good part of the supplies carried by the fleet would’ve been consumed anyway, at least part of the boats would’ve been empty and so pulling them would’ve been completely useless. And in the case that (as Syvänne and Dodgeon & Lieu assume), the Roman fleet had reached the Tigris downstream from Ctesiphon / Vēh-Ardaxšīr, pulling it past the twin cities would’ve been simply impossible. Still, as almost all the sources (even Ammianus, who was present there) sharply criticize Julian’s decision, it’s to be assumed that the fleet still carried supplies, that now would have to be carried by the pack animals of the army. It’s now when the reason for the attacks of Suren’s cavalry against the pack animals of the army and against its foraging parties became sharply evident: the army simply lacked enough pack animals to carry all the supplies. And possibly it would have also lacked enough of them to pull the fleet upstream, unless Julian used part of his manpower to pull the boats (indeed, both Ammianus and Libanius name this as the reason for Julian’s decision).

A second council of war was held (at Noorda according to Zosimus, perhaps modern Djsir Nahrawan near the

river Tamarra) and the decision to head for Corduene (roughly modern Iraqi Kurdistan) rather than to return via Āsūrestān was agreed upon (or imposed by Julian). The army struck camp on 16 June and marched due north towards the river Douros (considered by most scholars to be the Diyala River). Let’s see Ammianus’ account:

Ammianus Marcellinus (Res Gestae Libri XXXI, XXIV, 8, 2-6):