7.1 THE EASTERN BORDERS OF ĒRĀNŠAHR. GENERAL INTRODUCTION AND DESCRIPTION OF MERV.

The lands, peoples and geographic features of the Middle East are quite well known to western readers, and the events of Late Antiquity that happened there are relatively well documented due to the large number of ancient sources that have arrived to us, and the (again relatively) large amount of archeological work that has been done in these areas.

But the same can’t be said about the lands that were included within the eastern limits of the sprawling Sasanian empire, or those which lay immediately across it. The lack of written sources for these very extensive territories dated to the IV century CE is almost absolute, and the void can only be filled with archaeology, numismatics (which have played a capital role during the last eighty years in the efforts by scholars to reconstitute the political history of Central and South-Central Asia before the start of the Islamic era. Due to this, I’ve thought that it would be advisable to write a geographical-historical introduction aimed towards a very rough general introduction to these lands, which were much larger in area than the relatively small war theater of the Middle East and which were inhabited by much larger populations, which were also very varied in the ethnical, cultural, religious and economic sense.

For a start, let’s quote again Ammianus Marcellinus’ work (Res Gestae, Book XXIII, 14):

This passage by Ammianus is the beginning of a long excursus in which the Roman author described the Sasanian empire and its regions (a lengthy and detailed description of the Sasanian empire which I have not quoted here). The list is also valuable because it can give us some sort of idea about the eastern territories included within the Sasanian empire in the 350s CE (which is always a very difficult task due to the lack of sources), or more accurately what contemporary Romans knew about the eastern regions of Ērānšahr, which does not necessarily coincide with historical reality. This must be obviously compared with eastern sources, archaeology and numismatics.

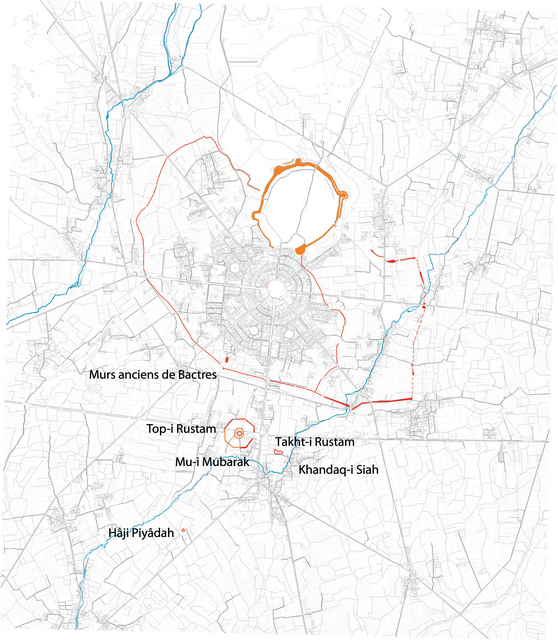

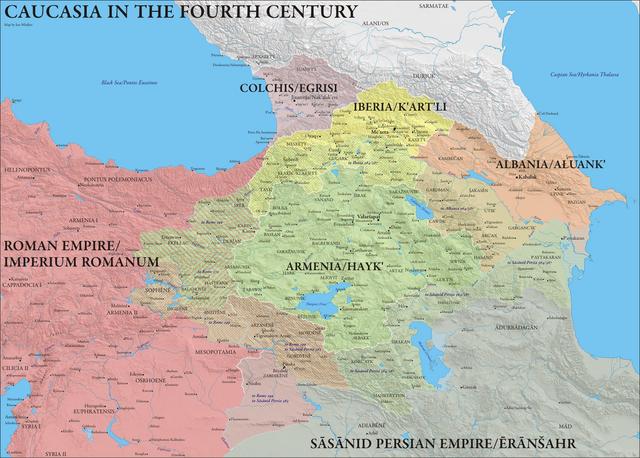

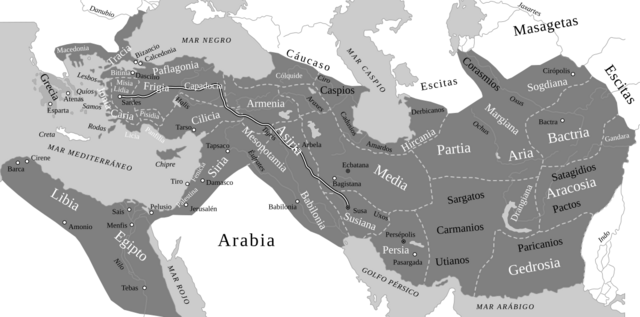

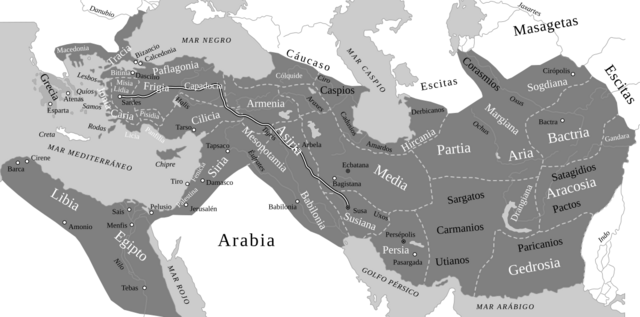

Map of the main satrapies of the Achaemenid empire; Classical authors kept using these to name the eastern territories until the end of Antiquity.

Margiana was to Greek and Roman geographers one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid empire which was centered around the large oasis of Merv.

With the Bactriani, Ammianus referred to the inhabitants of Bactria (or Bactriana) which was a region located north of the Hindu Kush mountain range and south of the Amu Darya river (ancient Oxus) covering the flat region that straddles modern-day Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

The Sogdiani refers to the inhabitants of Sogdia (or Sogdiana) was an ancient region centered on the main city of Samarkand. Sogdiana lay north of Bactria and east of Khwarezm between the Oxus (Amu Darya) and the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) rivers, centered around the fertile valley of the Zeravshan River. The territory of ancient Sogdia corresponds to the modern provinces of Samarkand and Bokhara in modern Uzbekistan as well as the Sughd province in modern Tajikistan.

With the Sacae, Ammianus might have meant the region of Sakastān (also spelled Sagestān in Middle Persian; modern Sīstān, today divided between Iran and Afghanistan). During the Achaemenid period it was known as Drangiana (Hellenized form of Old Western Iranian Zranka; the old name still survives in the name of the city of Zaranj in Afghanistan).

Scythia at the foot of the Imaus: in classical geography the term Mons Imaus was used loosely to refer to the two great chains of mountains that separate the Indian subcontinent from the rest of Asia: the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush. The term also was used to refer to all the mountain ranges in Central Asia, including the Pamir Plateau that separate the Tarim Basin from the Kashmir Valley and Sogdia, the Kunlun mountains that separate the Tibetan Plateau from the Tarim Basin and the Tian Shan mountain range that separates the Tarim Basin from the Eurasian steppe and the Altai mountain range north of the Tian Shan mountains. As for what did he mean by “Scythia”, here Ammianus was probably making a mess of names and places; the Sakas (or Sacae in Latin) were indeed Scythians, and they had during Arsacid times founded an Indo-Scythian kingdom that stretched both sides of the Hindu Kush, but referring to “Scythia at the foot of the Imaus” in the IV century CE was a complete anachronism that Ammianus probably picked out from some Greek geographer from several centuries before his time. Either that, or he was listing Sakastān twice.

Serica “beyond the Imaus”: this is a controversial point. Serica was the Roman name for China, and obviously the Sasanian empire never included any part of China. So, this could very well be yet another mistake by Ammianus. On the other side though, in the ŠKZ Šābuhr I claimed to have conquered Kashgar, an oasis in the easternmost extreme of the Tarim Basin, which was located east of the Pamir Plateau, and which had been under Chinese rule before the collapse of the Han empire. It seems highly improbable to me, but if Ammianus was not making another of his mistakes, this could mean that during the reign of Šābuhr II the Sasanians still were able to control somehow this easternmost point of the Tarim Basin.

Aria “beyond the Imaus”: this is another archaic term; Aria was an Achaemenid satrapy, which enclosed mostly the valley of the Hari River (Hareios in Greek) and which in antiquity was considered as particularly fertile and, above all, rich in wine. According to ancient geographers and writers like Strabo and Ptolemy, the region of Aria was separated by mountain ranges from the Paropamisadae in the east, Parthia in the west and Margiana and Hyrcania in the north, while a desert separated it from Carmania and Drangiana in the south. It is described in a very detailed manner by Ptolemy and Strabo and corresponds, according to their descriptions, almost exactly to the province of Herat in western Afghanistan.

The Paropanisadae “beyond the Imaus”. This is an interesting point; Paropamisadae is the Latinized form of the Greek name Paropamisádai which is in turn derived from Old Persian Parupraesanna; which means in turn "beyond the Hindu Kush". In Greek and Latin literary usage Paropamisus (Greek Paropamisós) came to mean eventually the Hindu Kush. And in Ptolemy’s Geography, the names of both the people and region are given as Paropanisadae and Paropanisus. According to the descriptions by Strabo and Ptolemy, the region was located north of Arachosia, stretching up to the Hindu Kush and Pamir mountains, and bordered the Indus River in the east. It included mainly the Kabul region, Gandhāra and the northern regions of the Swat and Chitral valleys, in modern northeastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan.

Drangiana “beyond the Imaus”: probably it’s yet another mistake by Ammianus. As I said before, Drangiana was just the archaic name of Sakastān/Sīstān.

Arachosia “beyond the Imaus” is the Hellenized name of an ancient Achaemenid satrapy. Arachosia was centered around the Arghandab River valley in southern Afghanistan, although its borders extended east to as far as the Indus River. The Arghandab River was called Arachōtós (hence its Greek name Arachōsíā) in ancient Greek texts and is a tributary of the Helmand River. This region corresponds the “Aryan” land of Harauti as mentioned in Avestan texts. The main city of Arachosia was the city of Kandahār in modern Afghanistan. According to the ancient geographers, Arachosia bordered Drangiana to the west, the Paropamisadae to the north, and Gedrosia to the south.

Gedrosia “beyond the Imaus”: Gedrosia (Γεδρωσία) is the Hellenized name of the part of coastal Baluchistan that roughly corresponds to the modern region of Makran, which is lays between Pakistan and Iran. Ancient Gedrosia ran from the Indus River to the southern edge of the Strait of Hormuz. It was located directly to the south of Bactria, Arachosia and Drangiana, limited with Carmania (Kermān in New Persian) in the east and the Indus River to the east.

So, this is what, according to Ammianus Marcellinus, the Romans knew about the eastern confines of Ērānšahr in the mid-IV century CE (remember that in this passage he was describing the array of the Sasanian army that invaded Roman Mesopotamia in 359 CE). This does not mean necessarily that this knowledge was correct. The list of lands and countries given by Ammianus is remarkably similar to the one that appears in the inscription of Šābuhr I at Naqš-e Rostam in Pārs (in the inscription usually referred to as ŠKZ), and which scholars usually consider as having been the maximum eastern extent of the Sasanian empire ever (or at least before Xusrō I and the Turkish Khaganate destroyed the Hephtalite empire during the first half of the VI century CE). The only difference between Ammianus’ list and the one that appears in the ŠKZ is that Šābuhr I claimed to rule also over Xwārazm (ancient Chorasmia, where the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers end at the Sea of Aral), but Chorasmia does not appear in Ammianus’ lists.

The problem is that scholars are already suspicious about the claims made by Šābuhr I, and they usually consider that Sasanian influence over the vast spaces of Central and Southern Asia (or over the area that the historian Khodadad Rezakhani calls “Eastern Iran”, referring to the land that in Antiquity and Early Middle Ages belonged to the wider “Persianate” cultural world and which were mostly -but not always- inhabited by Iranian-speaking populations) must have declined under Šābuhr I’s successors, given the troubles that they encountered even in their core territories in the Iranian plateau.

If we take Ammianus Marcellinus’ account as accurate (of which I’m far from convinced), that would mean that under Šābuhr II the Sasanians still controlled most of the territories acquired by Šābuhr I. But even if that were the case, it would be still open to discussion what sort of authority the Sasanian kings exerted over these territories.

In order to ascertain this, historians need to look for clues in archaeology, numismatics and explore eastern accounts that have been usually sidelined by western scholars. For now, the best clues are those offered by numismatics. The only eastern mint in which all the Sasanian kings between Ardaxšir I and Šābuhr II minted coins without interruptions was Marv. During Šābuhr II’s reign, coins bearing the effigy and name of this Šāhān Šāh also began to be minted at Herat, Balkh or Kabul. In fact, according to Touraj Daryaee, most gold dinars issued by Šābuhr II seem to have come from eastern mints (although this is tricky to determine, because Sasanian coins only began to show the mint where they were issued in a systematic way under Šābuhr II’s successor Ardaxšir II). What’s more telling though is that Balkh had been the capital of the Kušān Šāhs, and Herat and Kabul (as well as other mints in Bactria and Gandhāra) had belonged to their kingdom as well, and before the mid-IV century CE, only coins bearing the figure and the name of the ruling Kušān Šāh were issued by these mints; what seems to have happened is that they were replaced by “imperial” Sasanian issues bearing the name of the Šāhān Šāh Šābuhr II. According to Rezakhani, the last Kušān Šāh attested is Bahrām, who must’ve ruled (according to this scholar) between 330 and 365 CE.

Let’s take now a look at all these vast territories to see what they were like and what call archaeology, numismatics and ancient sources tell us about them. What appears immediately clear after a cursory look at a map is that these territories were vast, much larger than the areas disputed between the Sasanians and Romans in the Near East, and even larger than the Iranian heartland in the Iranian plateau itself. And they were not poor or deserted territories; some of these lands were densely populated and were agriculturally rich (and had also vital mining resources), but above everything else they sat across the most important land routes of transcontinental Eurasian trade. This will be a long task, and I will divide it into three main areas: Bactria, central Afghanistan and Gandhara, which since Kushan times were most of the time included in a single political entity and which shared many cultural traits. The, Sogdia, Khwarazm and the territories to the north of the Syr Darya (ancient Jaxartes) and across the Pamir that were closely linked to the trading cities of Sogdia, and finally the peripheral and rather poorly attested territories of southern Afghanistan and Pakistan (Arachosia, Gedrosia and Sindh). As a preface, I will start this general survey with a description of the land that was known to the classical geographers as Margiana, after the name of its main oasis, that of Merv (Marv in Middle Persian).

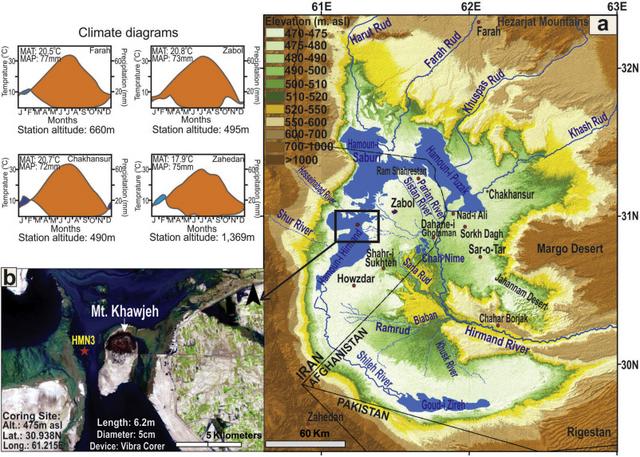

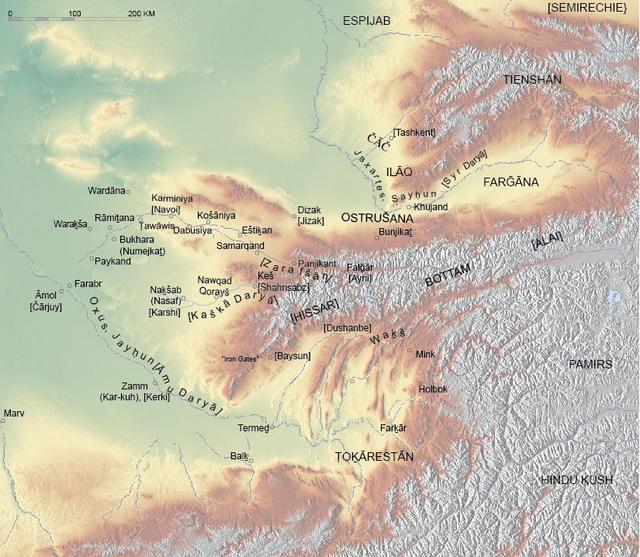

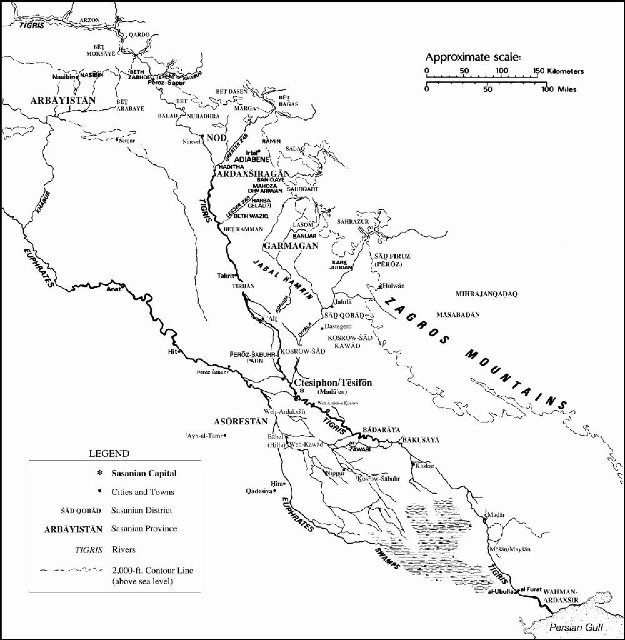

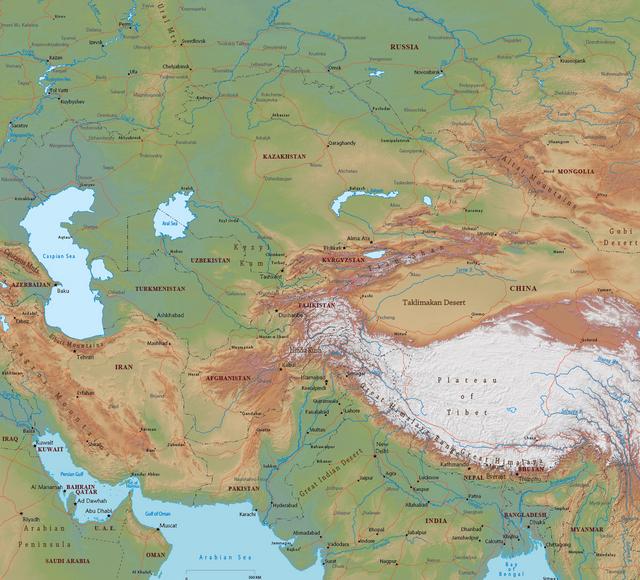

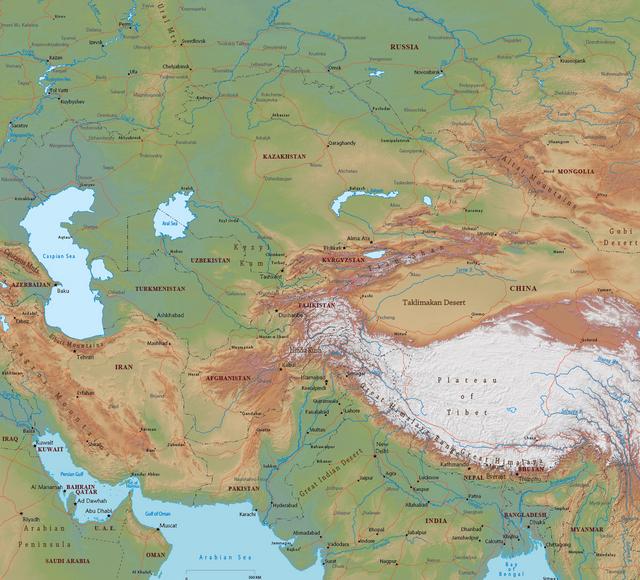

Physical map of Central Asia.

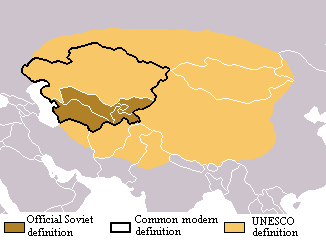

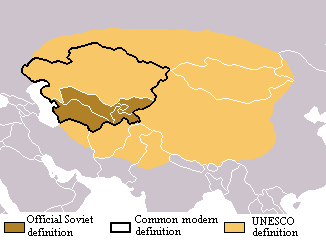

There are three possible ways to define "Central Asia". in this post, I will be using the UNESCO definition, as it covers an area that shared many cultural, political and economic common features during Late Antiquity.

After the end of the last glacial period, Central Asia was spotted with lakes (mostly saltwater lakes) as a residual remain of the melted glaciers. Due to the rather low rain regime, most of Central Asia has underwent since then a gradual process of desiccation, with the lakes slowly drying up, as the water influx from the main mountain ranges that are distributed across the region has been usually insufficient to compensate the effects of evaporation. Central Asia is situated at the center of the largest landmass of the planet and is surrounded to the south and east by high-altitude mountain ranges that cast a large rain shadow across the area and keep most of the moisture from the Indian Ocean monsoons from reaching it. For clarity’s sake, I will divide the Central Asian territories involved in the events narrated in this thread into five main areas:

The Tarim Basin.

The land of Margiana (Marv in Middle Persian) was centered around the large oasis of Merv, which covers now (with modern irrigation) an area of 4,900 km2. It has been associated for a very long time with the successive Iranian empires and the Zoroastrian tradition; it’s quoted in the Avesta (Mehr Yašt, 10.14) as Môuru, and in Achaemenid inscriptions in Old Persian as Marguš (from where the Greek term Margianḗ was derived). Merv was known to the Romans, for it appears in the Tabula Peutingeriana, an ancient Roman road map (itinerarium) dated to the IV century CE. The reason for its long and distinguished history is its location in the middle of the Kara Kum desert (“black sand” in Turkic) in present-day Turkmenistan, midway between Balkh, the Oxus and Nēv-Šābuhr, which made it an almost compulsory stop in the trade routes between the Iranian Plateau and Sogdia to the north and Bactria to the East (and respectively, to China and India). It was the main entry into the Iranian plateau for the great trans-Eurasian caravan route known as the Silk Road, and so probably it fulfilled a very important role also as a customs post. It also possibly marked the limit of direct “central” control by the Šāhān Šāh over the land; to the north lay Sogdia ruled by local princes, and to the east Bactria, which was until 365 CE (at least nominally) under the rule of the Kušān Šāh as a Sasanian “sub-king” ruling over a satellite state. The real golden era of Marv though would come during the Islamic era, when it skyrocketed to become one of the largest cities in the whole world until its destruction by the Mongols in 1221 CE.

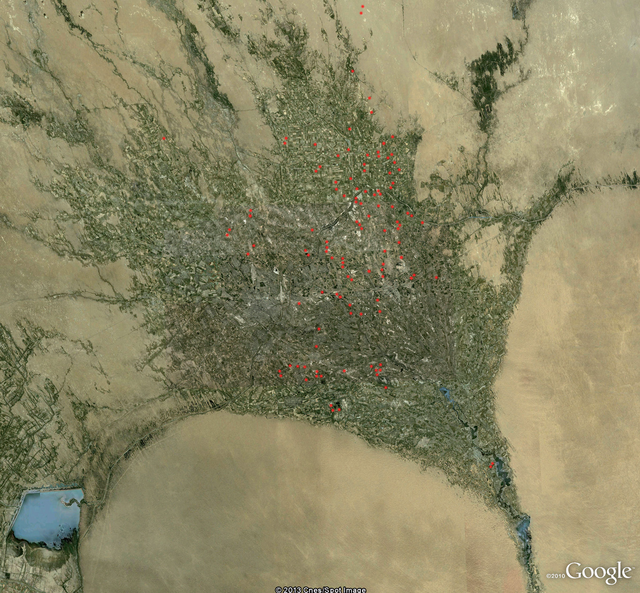

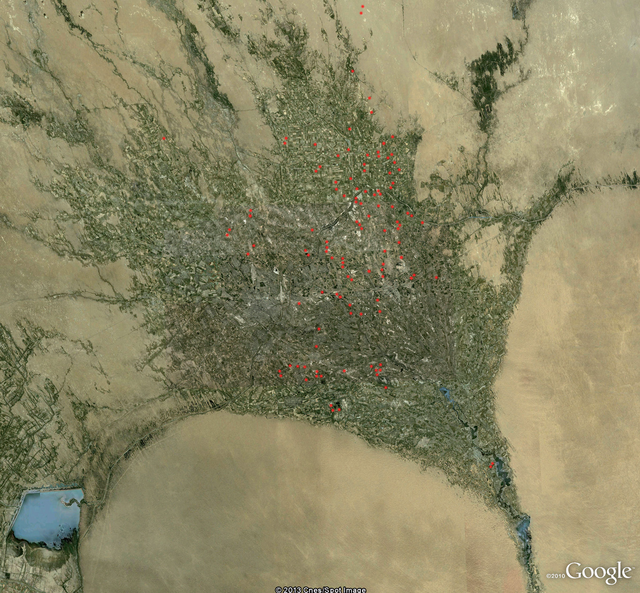

Satellite picture of the Merv oasis, with the archaeological sites dated to the Sasanian era marked with red dots (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

Nowadays the oasis supports a population in excess of one million people. Before the advent of modern transport, it was the last major center before caravans embarked on the long 180 km trip across the barren expanses of the Kara Kum desert to Amul (modern Chardzjou or “Four Canals”). Amul was a crossing point over the Oxus; from Amul it’s easy to reach Bukhara in Sogdia (and then continue to China) or continue upstream towards Termez and Bactria (and from there to India).

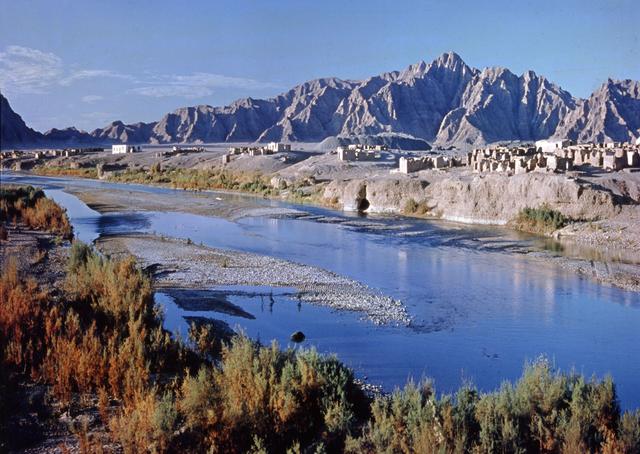

The Merv oasis is formed by alluvial silts deposited by the Murghab river. The Murghab rises in the Afghan mountains, crosses the desert and enters the oasis at its southern tip, where it is dammed (nowadays by no less than six dams, but anciently there was only one dam) before it fans out into a vast delta that then dries out into the sands of the Kara Kum desert. There is a Chinese report by Du Huan, written in 765 CE after his return from ten years spent as a captive in Merv, where he described:

Agriculture in the Merv oasis has always been dependent on artificial irrigation, nowadays as it was in ancient times, although the modern landscape has been radically altered by the arrival of the Kara Kum canal in 1954, which crosses the oasis from east to west, and has increased considerably the potential for irrigation at the Merv oasis and at the smaller Tedzhen oasis further to the west. As a result, the Merv oasis is probably at its maximum extent; in a 1991 map it measured 85x74 km. And this area has since been enlarged, because areas in the north, unused since the Bronze age, are now irrigated. Interestingly though, the 1991 area is similar to the one recorded by Du Huan:

The Merv oasis is one of the archaeological areas most intensively studied in Central Asia. In the 1950s, E.M. Masson of Tashkent University set up the YuTAKE, the South Turkmenistan Multi-Disciplinary Archaeological Expedition of the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan, which subjected the oasis of Merv to several prolonged archaeological studies. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the International Merv Project (IMO) was set up as a collaboration between University College London, YuTAKE, the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan and the Institute for the History of Material Culture, St. Petersburg.

The oasis of Merv has been inhabited at least since Neolithic times, and the oldest urban settlement that can be found within it is the site of Erk Kala, which has been dated to the VI century BCE, coinciding with the annexation of the area into the Achaemenid empire, or perhaps its predecessor the Median empire. Merv, or Margiana, is quoted in the great inscription of Darius I at Bīsotūn near Kermanshah in Iran as part of his empire, included in the great satrapy of Bactria. The next step in the urban development of Merv was the foundation by the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter (281-261 BCE) or the Greek metropolis of Antiochia in Margiana; of which the ancient city at Erk Kala became its citadel. The site occupied by the new Seleucid city at the foot of the Erk Kala citadel is known nowadays as Gyaur Kala.

Satellite view of the ancient city of Marv. The poligonal structure in the upper part of the picture is the Erk Kala citadel; and the part surrounded by a roughly square ruined wall is the lower city (Gyaur Kala). The main gates and the main roads that quartered the city can still be seen in this image (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

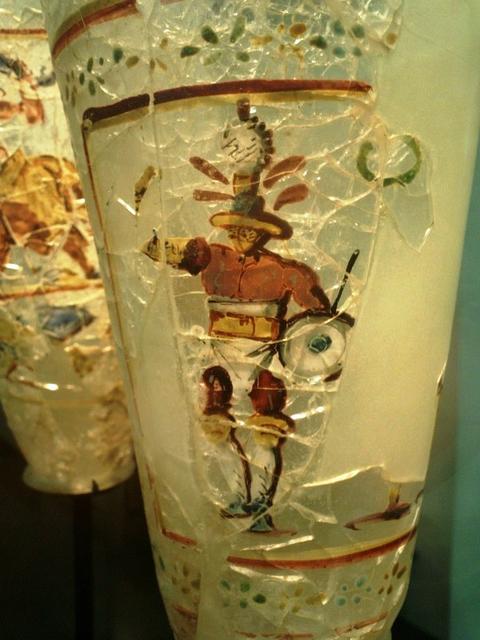

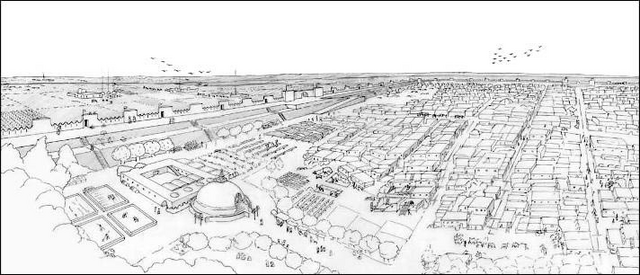

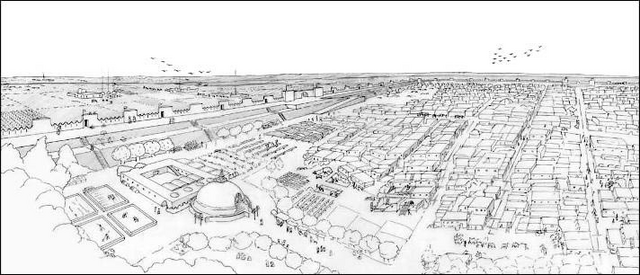

Artist's reconstruction of the ancient city of Marv from the southeastern corner of the city, with the Buddhist stupa in first term.

Aerial view of the Erk Kala citadel, seen from the northwest.

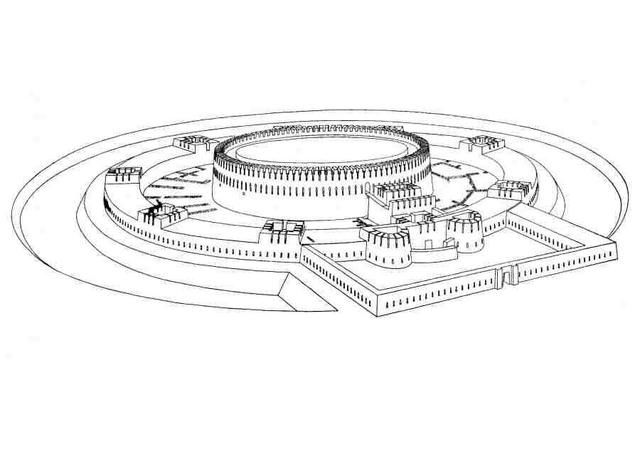

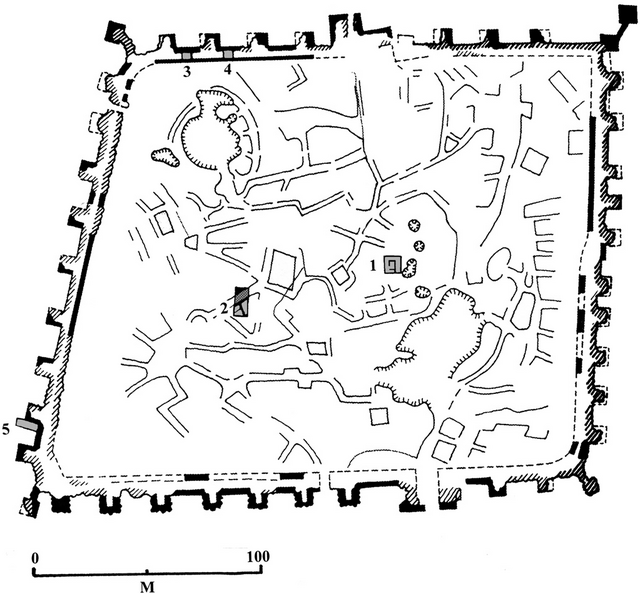

This was to become later the Arsacid and Sasanian city of Marv. It was located in the east central part of the oasis and lies next to the Razik canal; the main channel of the river Murghab flows much further to the west. At first sight, he site is dominated by the massive remains of the polygonal citadel at Erk-Kala which towers over a roughly square lower city (Gyaur Kala) which measures 2 km across; together they cover an area of some 374 ha. Each was encased within massive fortifications consisting of hollow curtains with external plastered glacises, which were constructed during the Sasanian period above the solid in-filled remains of earlier fortifications (Seleucid and Arsacid). The bulk of the built environment within the city connected the main east and west gates in a rectangle covering an approximate area of 125 ha. Additional residential quarters sprawled towards the south and north gates and added an additional 28 ha. or so to the built-up area. Each of these gates was situated midway along the curtain except on the north side where the central position of the citadel meant that the gate on this side was off-center, positioned directly to the east and commanded by a bastion of the citadel. It can be deduced from their morphology that all of the gates possessed a projecting outer wall and were approached by a ramp running parallel to the curtain. The curtain walls had towers at regular intervals, and excavations next to the southwest corner bastion revealed a sequence of redesign, constant use and strengthening of the fortifications during the four centuries of Sasanian rule. A fifth gate was situated on the western wall but bypassed the residential quarters and led into an open area on the western side of the citadel. Archaeologists believe that this area within the walls was substantially unoccupied in antiquity for a reason. Given the existence of the separate gate, it seems most likely that this area was limited to official and military activity, used for drilling and providing space for the horses which made up an essential part of the Sasanian army. In any case, its location suggests it was limited to military and official activity.

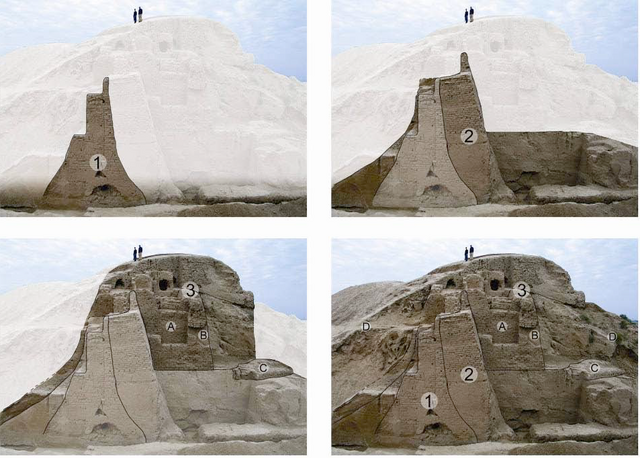

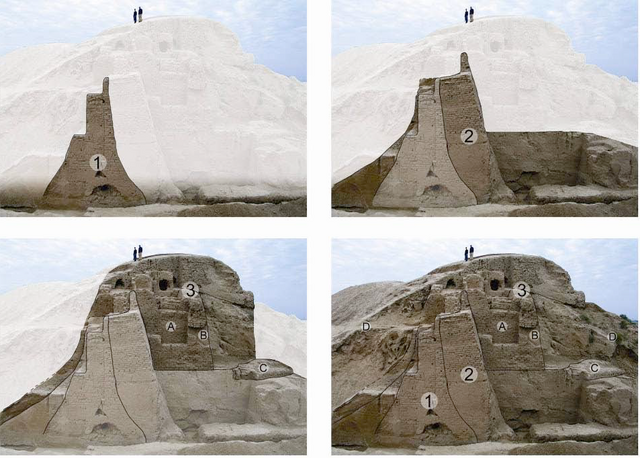

Evolution of the walls that surrounded Gyaur Kala across the centuries.

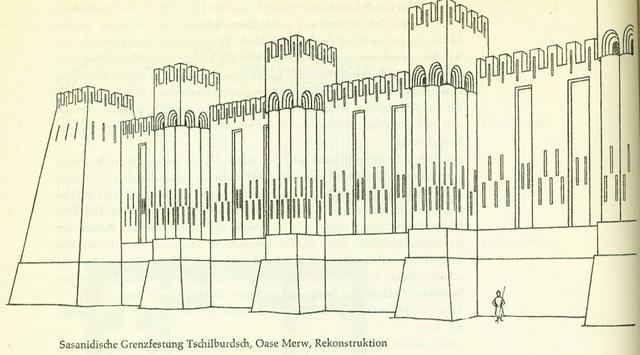

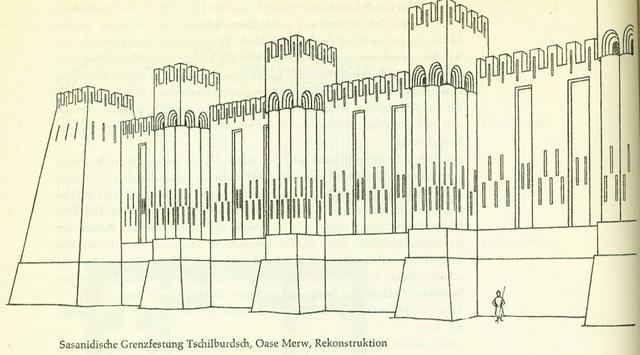

Hypothetic reconstruction of the walls around the Sasanian city of Marv.

Apart from the main city of Marv, other smaller forts dotted the oasis; the whole complex, would become the main eastern stronghold of the Arsacid and Sasanian empires against their eastern enemies (Kushans, Huns and Turks). One of the most important mints of the empire was located here, in order to pay its large garrison and the large armies that the Sasanian kings assembled there for their eastern campaigns. At this time, it was almost assuredly under the direct rule of the Šāhān Šāh, and due to its strategic situation and its imposing fortifications, it was the main military base for the Sasanian spāh during any campaign in Central Asia. In short, the oasis of Merv had a key strategic importance both for defending the exposed north-eastern border of the empire against Central Asian invaders and to block them entry into the Iranian Plateau and the heart of Ērānšahr, but also for projecting Sasanian military power into Bactria, Sogdia and beyond.

Archaeologists have identified up to 162 settlements dated to the Sasanian period within the oasis; as well as a complex irrigation network that was mostly built in Arsacid times. Of these settlements, a total of 133 sites covered an area of less than 4 ha., therefore falling within the category of village or hamlets according to Sasanian standards; an additional 17 sites covered areas of up to 30 ha. and thus, may be regarded as equivalent in size to a town, but only three exceeded that. To archaeologists, this must imply a high level of rural development in the hinterland of the city of Marv, with a cluster of settlements along the course of the Murghab, as well as along canals flowing due north. Many of these Sasanian settlements appear to have been built on artificial platforms (dakhma) raised above the alluvial plain and surrounded by ditches and moats. Archaeological digs at two of these raised mounds (called kalas and tepes in the local Turkic language) at Göbekli-tepe and Chilburj have revealed that they were substantially fortified, with walls and towers that were rebuilt and reinforced during Sasanian rule.

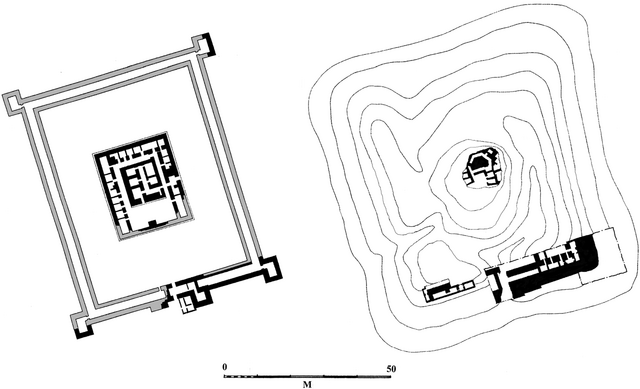

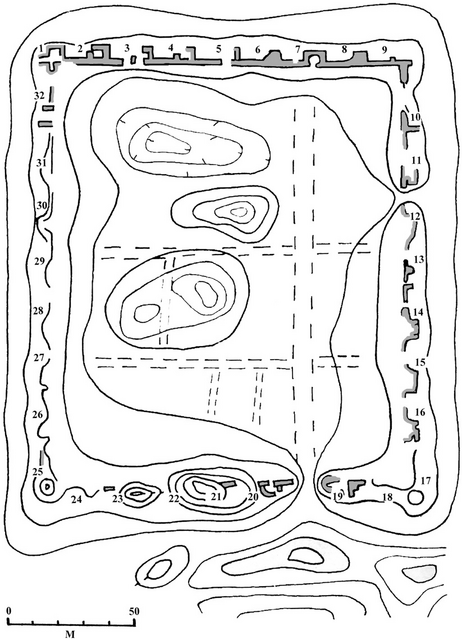

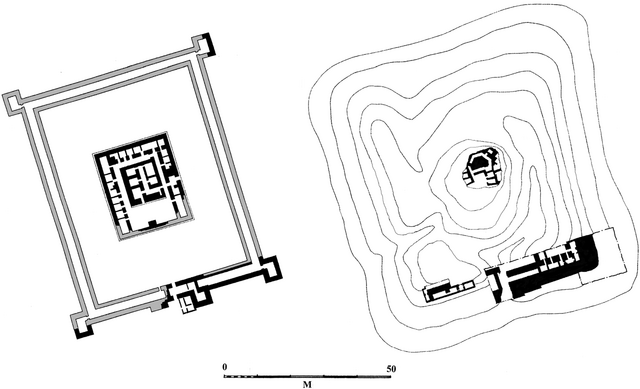

Plan of the remains of the settlement at Göbekli-tepe (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

The case of Chilburj is particularly interesting. Soviet excavations in 1980 dated the present remains to the V century CE, although it seems to have an Arsacid origin. The main portion of the settlement consists of an almost square site covering some 2.7 ha. and surrounded by a hollow curtain wall with square projecting interval towers. It had a heavily defended gatehouse on the southern side, a similar construction on the north side which was presumably blocked at a later date (perhaps in a moment of siege or military crisis), and elongated corner towers which were probably designed to enable torsion artillery to block access to the gates in case of a siege. And the case of the fort at Chilburj is not the only one in the oasis of Merv.

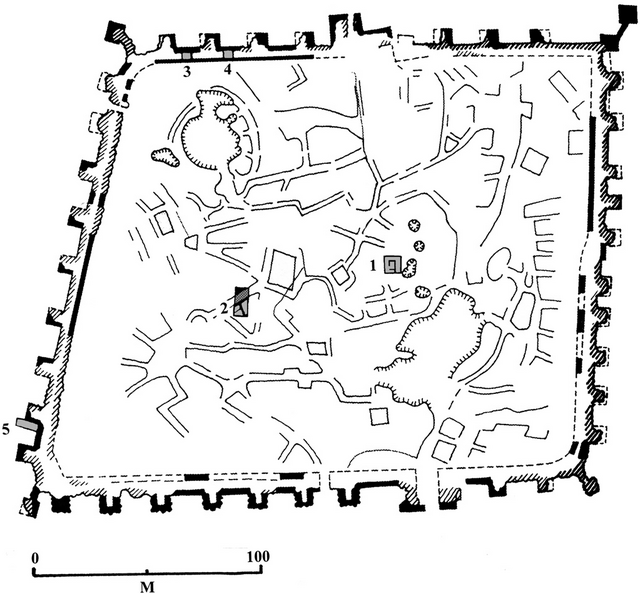

Archaeological drawing and aerial photograph of the remains of the Sasanian fort at Chilburj in the Merv oasis (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

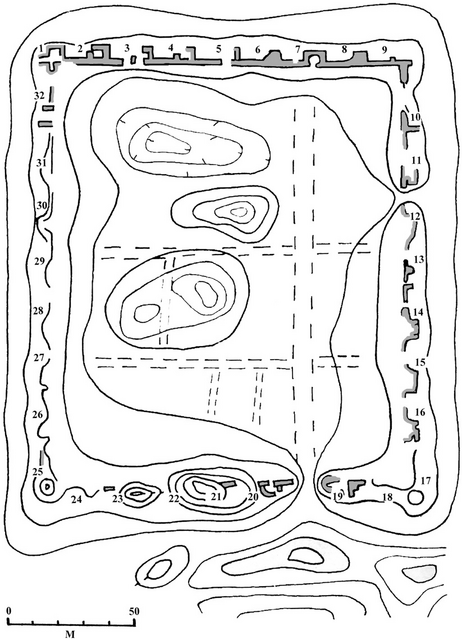

Another typology of fort is found at Durnali, rectangular in shape, with regularly placed square towers projecting from the wall, while the area within the walls was divided by rectilinear streets and alleys in an orderly fashion; immediately to the south of the fort, archaeologists have found an extramural settlement of some 7 ha. which has been dated to the late V to VII centuries CE. A third typology appears at the northern edge of the site of Köne Kishman; in here archaeologists were puzzled by the fact that apparently the enclosed space within the walls lacks any trace of occupation. One possible explanation for this is that it was a campaign fort which originally enclosed rows of tents rather than permanent barracks, in a similar way to the forts that have been excavated along the Gorgan Wall further to the west. This strongly suggests that the whole oasis was provided at some point in time with an array of fortified spaces designed to lodge a large campaign army with plenty of space within their walls, as would befit a cavalry-heavy army. Apart from its commercial and agricultural importance, the Merv oasis was a huge military basis for the Sasanian spāh and the main jumping post for its campaigns in Central Asia, both in Sogdia to the north and Bactria to the east.

Archaeological drawing and aerial photograph of the remains of the Sasanian fort at Durnali in the Merv oasis (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

The archaeological evidence therefore suggests a militarized yet prosperous pattern of settlement in the oasis with a high density of settlements of different sizes, some walled and some apparently unwalled, with the largest center being the city of Marv itself. Literary sources consistently praise the rich agricultural resources of the Merv oasis during the Classical and Islamic periods. Although equivalent written sources are lacking for the Sasanian period, archaeologists think it’s reasonable to extrapolate a similar situation for Sasanian times, and there is evidence for major canal off-takes from the river Murghab at this period. An important find in the oasis of Merv was the discovery of large quantities of accidentally carbonized cotton seeds in contexts dating from the IV century CE onwards, which provides the earliest archaeobotanical evidence for cultivation of this fiber crop in the oasis and contradicts the hypothesis that cotton cultivation was introduced as late as the IX century CE.

The population of the oasis before it became Turkicized during the late Middle Age was formed by Iranian speakers, who probably spoke originally a dialect of Parthian; the use of Parthian in written form is attested still in the IV century CE. When the city surrendered to the armies of the Rashidun Caliphate in 651 CE, the population of the city and the oasis was predominantly Zoroastrian, but the city also hosted large and vital Manichean, Jewish, Nestorian Christian and Buddhist communities, with a large Buddhist monastery and stupa occupying the southeast corner of the city. The oasis of Merv was controlled by the Sasanian dynasty since the times of Ardaxšir I until the Islamic conquest, being only lost for a short timespan to the Hephtalites during the late V and early VI centuries CE; scholars are quite sure of this because all the Sasanian kings minted coins here except for the aforementioned time period.

The lands, peoples and geographic features of the Middle East are quite well known to western readers, and the events of Late Antiquity that happened there are relatively well documented due to the large number of ancient sources that have arrived to us, and the (again relatively) large amount of archeological work that has been done in these areas.

But the same can’t be said about the lands that were included within the eastern limits of the sprawling Sasanian empire, or those which lay immediately across it. The lack of written sources for these very extensive territories dated to the IV century CE is almost absolute, and the void can only be filled with archaeology, numismatics (which have played a capital role during the last eighty years in the efforts by scholars to reconstitute the political history of Central and South-Central Asia before the start of the Islamic era. Due to this, I’ve thought that it would be advisable to write a geographical-historical introduction aimed towards a very rough general introduction to these lands, which were much larger in area than the relatively small war theater of the Middle East and which were inhabited by much larger populations, which were also very varied in the ethnical, cultural, religious and economic sense.

For a start, let’s quote again Ammianus Marcellinus’ work (Res Gestae, Book XXIII, 14):

Now there are in all Persia these greater provinces, ruled by vitaxae, or commanders of cavalry, by kings, and by satraps (for to enumerate the great number of smaller districts would be difficult and superfluous) namely, Assyria, Susiana, Media, Persis, Parthia, Greater Carmania, Hyrcania, Margiana, the Bactriani, the Sogdiani, the Sacae, Scythia at the foot of Imaus, and beyond the same mountain, Serica, Aria, the Paropamisadae, Drangiana, Arachosia, and Gedrosia.

This passage by Ammianus is the beginning of a long excursus in which the Roman author described the Sasanian empire and its regions (a lengthy and detailed description of the Sasanian empire which I have not quoted here). The list is also valuable because it can give us some sort of idea about the eastern territories included within the Sasanian empire in the 350s CE (which is always a very difficult task due to the lack of sources), or more accurately what contemporary Romans knew about the eastern regions of Ērānšahr, which does not necessarily coincide with historical reality. This must be obviously compared with eastern sources, archaeology and numismatics.

Map of the main satrapies of the Achaemenid empire; Classical authors kept using these to name the eastern territories until the end of Antiquity.

Margiana was to Greek and Roman geographers one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid empire which was centered around the large oasis of Merv.

With the Bactriani, Ammianus referred to the inhabitants of Bactria (or Bactriana) which was a region located north of the Hindu Kush mountain range and south of the Amu Darya river (ancient Oxus) covering the flat region that straddles modern-day Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

The Sogdiani refers to the inhabitants of Sogdia (or Sogdiana) was an ancient region centered on the main city of Samarkand. Sogdiana lay north of Bactria and east of Khwarezm between the Oxus (Amu Darya) and the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) rivers, centered around the fertile valley of the Zeravshan River. The territory of ancient Sogdia corresponds to the modern provinces of Samarkand and Bokhara in modern Uzbekistan as well as the Sughd province in modern Tajikistan.

With the Sacae, Ammianus might have meant the region of Sakastān (also spelled Sagestān in Middle Persian; modern Sīstān, today divided between Iran and Afghanistan). During the Achaemenid period it was known as Drangiana (Hellenized form of Old Western Iranian Zranka; the old name still survives in the name of the city of Zaranj in Afghanistan).

Scythia at the foot of the Imaus: in classical geography the term Mons Imaus was used loosely to refer to the two great chains of mountains that separate the Indian subcontinent from the rest of Asia: the Himalayas and the Hindu Kush. The term also was used to refer to all the mountain ranges in Central Asia, including the Pamir Plateau that separate the Tarim Basin from the Kashmir Valley and Sogdia, the Kunlun mountains that separate the Tibetan Plateau from the Tarim Basin and the Tian Shan mountain range that separates the Tarim Basin from the Eurasian steppe and the Altai mountain range north of the Tian Shan mountains. As for what did he mean by “Scythia”, here Ammianus was probably making a mess of names and places; the Sakas (or Sacae in Latin) were indeed Scythians, and they had during Arsacid times founded an Indo-Scythian kingdom that stretched both sides of the Hindu Kush, but referring to “Scythia at the foot of the Imaus” in the IV century CE was a complete anachronism that Ammianus probably picked out from some Greek geographer from several centuries before his time. Either that, or he was listing Sakastān twice.

Serica “beyond the Imaus”: this is a controversial point. Serica was the Roman name for China, and obviously the Sasanian empire never included any part of China. So, this could very well be yet another mistake by Ammianus. On the other side though, in the ŠKZ Šābuhr I claimed to have conquered Kashgar, an oasis in the easternmost extreme of the Tarim Basin, which was located east of the Pamir Plateau, and which had been under Chinese rule before the collapse of the Han empire. It seems highly improbable to me, but if Ammianus was not making another of his mistakes, this could mean that during the reign of Šābuhr II the Sasanians still were able to control somehow this easternmost point of the Tarim Basin.

Aria “beyond the Imaus”: this is another archaic term; Aria was an Achaemenid satrapy, which enclosed mostly the valley of the Hari River (Hareios in Greek) and which in antiquity was considered as particularly fertile and, above all, rich in wine. According to ancient geographers and writers like Strabo and Ptolemy, the region of Aria was separated by mountain ranges from the Paropamisadae in the east, Parthia in the west and Margiana and Hyrcania in the north, while a desert separated it from Carmania and Drangiana in the south. It is described in a very detailed manner by Ptolemy and Strabo and corresponds, according to their descriptions, almost exactly to the province of Herat in western Afghanistan.

The Paropanisadae “beyond the Imaus”. This is an interesting point; Paropamisadae is the Latinized form of the Greek name Paropamisádai which is in turn derived from Old Persian Parupraesanna; which means in turn "beyond the Hindu Kush". In Greek and Latin literary usage Paropamisus (Greek Paropamisós) came to mean eventually the Hindu Kush. And in Ptolemy’s Geography, the names of both the people and region are given as Paropanisadae and Paropanisus. According to the descriptions by Strabo and Ptolemy, the region was located north of Arachosia, stretching up to the Hindu Kush and Pamir mountains, and bordered the Indus River in the east. It included mainly the Kabul region, Gandhāra and the northern regions of the Swat and Chitral valleys, in modern northeastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan.

Drangiana “beyond the Imaus”: probably it’s yet another mistake by Ammianus. As I said before, Drangiana was just the archaic name of Sakastān/Sīstān.

Arachosia “beyond the Imaus” is the Hellenized name of an ancient Achaemenid satrapy. Arachosia was centered around the Arghandab River valley in southern Afghanistan, although its borders extended east to as far as the Indus River. The Arghandab River was called Arachōtós (hence its Greek name Arachōsíā) in ancient Greek texts and is a tributary of the Helmand River. This region corresponds the “Aryan” land of Harauti as mentioned in Avestan texts. The main city of Arachosia was the city of Kandahār in modern Afghanistan. According to the ancient geographers, Arachosia bordered Drangiana to the west, the Paropamisadae to the north, and Gedrosia to the south.

Gedrosia “beyond the Imaus”: Gedrosia (Γεδρωσία) is the Hellenized name of the part of coastal Baluchistan that roughly corresponds to the modern region of Makran, which is lays between Pakistan and Iran. Ancient Gedrosia ran from the Indus River to the southern edge of the Strait of Hormuz. It was located directly to the south of Bactria, Arachosia and Drangiana, limited with Carmania (Kermān in New Persian) in the east and the Indus River to the east.

So, this is what, according to Ammianus Marcellinus, the Romans knew about the eastern confines of Ērānšahr in the mid-IV century CE (remember that in this passage he was describing the array of the Sasanian army that invaded Roman Mesopotamia in 359 CE). This does not mean necessarily that this knowledge was correct. The list of lands and countries given by Ammianus is remarkably similar to the one that appears in the inscription of Šābuhr I at Naqš-e Rostam in Pārs (in the inscription usually referred to as ŠKZ), and which scholars usually consider as having been the maximum eastern extent of the Sasanian empire ever (or at least before Xusrō I and the Turkish Khaganate destroyed the Hephtalite empire during the first half of the VI century CE). The only difference between Ammianus’ list and the one that appears in the ŠKZ is that Šābuhr I claimed to rule also over Xwārazm (ancient Chorasmia, where the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers end at the Sea of Aral), but Chorasmia does not appear in Ammianus’ lists.

The problem is that scholars are already suspicious about the claims made by Šābuhr I, and they usually consider that Sasanian influence over the vast spaces of Central and Southern Asia (or over the area that the historian Khodadad Rezakhani calls “Eastern Iran”, referring to the land that in Antiquity and Early Middle Ages belonged to the wider “Persianate” cultural world and which were mostly -but not always- inhabited by Iranian-speaking populations) must have declined under Šābuhr I’s successors, given the troubles that they encountered even in their core territories in the Iranian plateau.

If we take Ammianus Marcellinus’ account as accurate (of which I’m far from convinced), that would mean that under Šābuhr II the Sasanians still controlled most of the territories acquired by Šābuhr I. But even if that were the case, it would be still open to discussion what sort of authority the Sasanian kings exerted over these territories.

In order to ascertain this, historians need to look for clues in archaeology, numismatics and explore eastern accounts that have been usually sidelined by western scholars. For now, the best clues are those offered by numismatics. The only eastern mint in which all the Sasanian kings between Ardaxšir I and Šābuhr II minted coins without interruptions was Marv. During Šābuhr II’s reign, coins bearing the effigy and name of this Šāhān Šāh also began to be minted at Herat, Balkh or Kabul. In fact, according to Touraj Daryaee, most gold dinars issued by Šābuhr II seem to have come from eastern mints (although this is tricky to determine, because Sasanian coins only began to show the mint where they were issued in a systematic way under Šābuhr II’s successor Ardaxšir II). What’s more telling though is that Balkh had been the capital of the Kušān Šāhs, and Herat and Kabul (as well as other mints in Bactria and Gandhāra) had belonged to their kingdom as well, and before the mid-IV century CE, only coins bearing the figure and the name of the ruling Kušān Šāh were issued by these mints; what seems to have happened is that they were replaced by “imperial” Sasanian issues bearing the name of the Šāhān Šāh Šābuhr II. According to Rezakhani, the last Kušān Šāh attested is Bahrām, who must’ve ruled (according to this scholar) between 330 and 365 CE.

Let’s take now a look at all these vast territories to see what they were like and what call archaeology, numismatics and ancient sources tell us about them. What appears immediately clear after a cursory look at a map is that these territories were vast, much larger than the areas disputed between the Sasanians and Romans in the Near East, and even larger than the Iranian heartland in the Iranian plateau itself. And they were not poor or deserted territories; some of these lands were densely populated and were agriculturally rich (and had also vital mining resources), but above everything else they sat across the most important land routes of transcontinental Eurasian trade. This will be a long task, and I will divide it into three main areas: Bactria, central Afghanistan and Gandhara, which since Kushan times were most of the time included in a single political entity and which shared many cultural traits. The, Sogdia, Khwarazm and the territories to the north of the Syr Darya (ancient Jaxartes) and across the Pamir that were closely linked to the trading cities of Sogdia, and finally the peripheral and rather poorly attested territories of southern Afghanistan and Pakistan (Arachosia, Gedrosia and Sindh). As a preface, I will start this general survey with a description of the land that was known to the classical geographers as Margiana, after the name of its main oasis, that of Merv (Marv in Middle Persian).

Physical map of Central Asia.

There are three possible ways to define "Central Asia". in this post, I will be using the UNESCO definition, as it covers an area that shared many cultural, political and economic common features during Late Antiquity.

After the end of the last glacial period, Central Asia was spotted with lakes (mostly saltwater lakes) as a residual remain of the melted glaciers. Due to the rather low rain regime, most of Central Asia has underwent since then a gradual process of desiccation, with the lakes slowly drying up, as the water influx from the main mountain ranges that are distributed across the region has been usually insufficient to compensate the effects of evaporation. Central Asia is situated at the center of the largest landmass of the planet and is surrounded to the south and east by high-altitude mountain ranges that cast a large rain shadow across the area and keep most of the moisture from the Indian Ocean monsoons from reaching it. For clarity’s sake, I will divide the Central Asian territories involved in the events narrated in this thread into five main areas:

- West Turkestan: a territory bordered to the south by the Iranian Plateau and the Hindu Kush mountain range, and to the east by the Pamir and Altai mountains, and by the Caspian Sea to the west. Its northern limits are less clear, it ends north of the Syr Darya, transforming into the central tract of the Eurasian steppe. Western Turkestan is crossed by two major rivers (Amu Darya and Syr Darya) which spring respectively from the Hindu Kush and Pamir mountains and meet (or rather used to meet) their end at the inland Aral Sea. In ancient times, the Amu Darya did not drain all of its waters into the Aral Sea; part of its current bypassed the Aral Sea to the south and reached the Sarykamysh Lake. From here, these water course (known as the Uzboy river) crossed the Karakum Desert and emptied into the Caspian Sea; the Uzboy dried up in the XVII century. Apart from these two major rivers, there’s also a number of smaller rivers which are either tributaries of the two larger rivers (like for example the Zerafshan river) or which simply meet their end in the sand of some of the deserts that cover most of this territory (like the Murghab river). Modern irrigation works have carried out by Soviet engineers during the XX century have altered considerably the hydrology of the region; other than the rather famous case of the Aral Sea, the Balkhab river also used to reach the Amu Darya, while today it dries up before reaching it. Western Turkestan is dotted with oasis, some small and others really large, situated in strategic places where the rivers fan out into deltas (like Balkh, or Khwarazm) or due to the topography of the land they allow the irrigation of large tracts of land (like at Bukhara and Samarkand). North of the Syr Darya there are also some settled areas that have during this time period were very influenced by Sogdia (and partly settled by Sogdians) but which were not part of Sogdia proper. One of these areas was the large oasis of Chach (modern Tashkent), on the banks of the Chirchik river (a tributary of the Syr Darya) and the valley of Ferghana, one of the most fertile and well-watered areas of Central Asia, which was a vital node of the Silk Road, as it was crossed by the main road that crossed the Pamir into the Tarim Basin and from there followed all the way to China.

- East Turkestan: much smaller than its western counterpart, it’s much more strictly delimited too. It’s formed basically by the Tarim Basin, which is surrounded by the Pamirs to the west, the Tian Shan range to the north (which separates it from the Dzungarian steppe) and the Kunlun mountains to the south, which form the northern buttress of the Tibetan Plateau. It lays open the East to the Gansu corridor that leads directly to central China and to the Northeast to the Gobi Desert and Mongolia through Turpan and Hami. Eastern Turkestan is much drier than Western Turkestan; when the glaciers of the last glacial period melted, the basin was occupied by an inner lake that underwent a progressive process of desiccation across the centuries. According to Chinese texts, by the time of the Han dynasty (II century BCE to III century CE) its eastern end was still covered by a large lake (the Lop Nur Lake) fed by the waters of the Tarim river which drained the melted snow from the Tian Shan and Kunlun ranges through several tributaries. Today, the Lop Nur lake is almost dried up and the Tarim river does not reach it. Most of the central part of the Tarim Basin if occupied by the Taklamakan Desert, and human population is concentrated along a series of irrigated oasis to its south and north, along the slopes of the Tian Shan and Kunlun mountains.

The Tarim Basin.

- The Eurasian Steppe occupies all the northern fringe of Central Asia, until it meets the Siberian Taiga. To the west lies the Central Steppe (or Kazakh Steppe), from the Urals to Dzungaria. It’s separated from the Eastern Steppe by the Dzungarian Narrowing, where the Altai and Tarbagatai Mountains which almost reach the northern forest leaving almost no grassland; to the east lie the Mongol Steppe and finally Manchuria. Although the steppe receives enough rainfall to allow grass to grow, water is too scarce and weather too unpredictable to allow the development of dry or irrigated farming before the XX century, so the human communities living there followed a nomadic lifestyle centered around herding and seasonal migration, although they also engaged occasionally in agriculture and built semi-permanent fortifications. Until the II century CE, the Kazakh Steppe had been dominated by Iranian-speaking peoples (speakers of eastern Iranian languages), but there was already a presence of confederations formed predominantly by non-Iranian speakers, like the Dingling and, according to contemporary scholars, the Huns who lived in the western approaches of the Altai Mountains after they were expelled from the Mongol Steppe by the rising Xianbei confederation during the mid-II century CE.

- South of West Turkestan and east of the Iranian plateau lay the Afghan highlands, which mostly coincide with the modern country of Afghanistan. These highlands are formed by the great mountain range of the Hindu Kush to the north, which runs along a Northeast (where it joins the Karakorum range and the Pamir) to Southwest axis, where it gradually fans out into lower altitude mountain ranges, which cover the central part of modern Afghanistan which is essentially a highland country of fertile valleys isolated from each other. The Hindu Kush and the mountain ranges that fan out from it are the main hydrological nod of this part of Asia; all the major rivers spring in them and are part of either the Indus river basin (all the rivers flowing east, like the Kabul river) or of landlocked riverine systems; the ones that flow to the south and the east (like the Arghandab and Helmand rivers) meet their end at the lakes of the Sistan Basin, and the ones which flow north (like the Murghab and Balkhab rivers) either fan out into deltas and disappear into the sands of the Karakum desert (like the Murghab river) or (in the past) are tributaries of the Amu Darya (like the Balkhab river). To the south of the country, the mountains lose height even more and form the Arachosian Plateau, a semi-desertic highland plain crossed by the Arghandab river where the city of Kandahar lies. To the west, the terrain descends even more, and gradually melts into the Sistan basin; this area is crossed by the Helmand river and its tributaries and here lie some important cities like Herat and Zaranj. Finally, to the north of the country, on the northern ramparts of the highland mountains lies a flat stretch of land which forms part of the Amu Darya valley and which contains the most fertile lands of the area, although watering depends on the streams that flow from the mountains. Today, this plain is partitioned between Afghanistan and Tadjikistan (and partly by Turkmenistan) but anciently this was the land of Bactria, or Tokharistan as the Sasanians called it; originally Bactria covered also central Afghanistan all the way to the partition of waters with the Indus river basin, but from the IV century CE onwards the Afghan highlands were progressively considered as a separate entity, and by the VI century CE it was divided into two countries; Kabulistān to the northeast and Zābulistān to the southwest.

- To the southwest of the Afghan highlands lies the Indus river valley, which was considered in Antiquity and the Middle Ages as an integral part of India (Hind in Middle Persian). According to modern scholars, the Sasanians could’ve controlled after the conquests of Šābuhr I perhaps all the right bank of the Indus; to the south lay the land known to Iranians as Sindh, with important sea ports (like the one excavated at Banbhore in Pakistan) and to the north lay the rich, populated and prestigious land of Gandhāra, which lay directly across the main land trade route between India and Central Asia, which from Puruṣapura (modern Peshawar) crossed the Khyber Pass following the valley of the Kabul river to the city of Kabul, and from Kabul crossed the Afghan highlands to Balkh, from where the route could lead to the west to Marv and the Iranian Plateau, or north to Sogdia and from there to the Ferghana valley and then eastwards to China (although there was a much more direct land route from India to China through Kashmir).

The land of Margiana (Marv in Middle Persian) was centered around the large oasis of Merv, which covers now (with modern irrigation) an area of 4,900 km2. It has been associated for a very long time with the successive Iranian empires and the Zoroastrian tradition; it’s quoted in the Avesta (Mehr Yašt, 10.14) as Môuru, and in Achaemenid inscriptions in Old Persian as Marguš (from where the Greek term Margianḗ was derived). Merv was known to the Romans, for it appears in the Tabula Peutingeriana, an ancient Roman road map (itinerarium) dated to the IV century CE. The reason for its long and distinguished history is its location in the middle of the Kara Kum desert (“black sand” in Turkic) in present-day Turkmenistan, midway between Balkh, the Oxus and Nēv-Šābuhr, which made it an almost compulsory stop in the trade routes between the Iranian Plateau and Sogdia to the north and Bactria to the East (and respectively, to China and India). It was the main entry into the Iranian plateau for the great trans-Eurasian caravan route known as the Silk Road, and so probably it fulfilled a very important role also as a customs post. It also possibly marked the limit of direct “central” control by the Šāhān Šāh over the land; to the north lay Sogdia ruled by local princes, and to the east Bactria, which was until 365 CE (at least nominally) under the rule of the Kušān Šāh as a Sasanian “sub-king” ruling over a satellite state. The real golden era of Marv though would come during the Islamic era, when it skyrocketed to become one of the largest cities in the whole world until its destruction by the Mongols in 1221 CE.

Satellite picture of the Merv oasis, with the archaeological sites dated to the Sasanian era marked with red dots (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

Nowadays the oasis supports a population in excess of one million people. Before the advent of modern transport, it was the last major center before caravans embarked on the long 180 km trip across the barren expanses of the Kara Kum desert to Amul (modern Chardzjou or “Four Canals”). Amul was a crossing point over the Oxus; from Amul it’s easy to reach Bukhara in Sogdia (and then continue to China) or continue upstream towards Termez and Bactria (and from there to India).

The Merv oasis is formed by alluvial silts deposited by the Murghab river. The Murghab rises in the Afghan mountains, crosses the desert and enters the oasis at its southern tip, where it is dammed (nowadays by no less than six dams, but anciently there was only one dam) before it fans out into a vast delta that then dries out into the sands of the Kara Kum desert. There is a Chinese report by Du Huan, written in 765 CE after his return from ten years spent as a captive in Merv, where he described:

(…) a big river which flows into its territory, where it divides into several hundred canals irrigating the whole area (…)

Agriculture in the Merv oasis has always been dependent on artificial irrigation, nowadays as it was in ancient times, although the modern landscape has been radically altered by the arrival of the Kara Kum canal in 1954, which crosses the oasis from east to west, and has increased considerably the potential for irrigation at the Merv oasis and at the smaller Tedzhen oasis further to the west. As a result, the Merv oasis is probably at its maximum extent; in a 1991 map it measured 85x74 km. And this area has since been enlarged, because areas in the north, unused since the Bronze age, are now irrigated. Interestingly though, the 1991 area is similar to the one recorded by Du Huan:

(…) the area of this kingdom from east to west is 140 li (70 km) and from north to south 180 li (90 km) (…)

The Merv oasis is one of the archaeological areas most intensively studied in Central Asia. In the 1950s, E.M. Masson of Tashkent University set up the YuTAKE, the South Turkmenistan Multi-Disciplinary Archaeological Expedition of the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan, which subjected the oasis of Merv to several prolonged archaeological studies. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the International Merv Project (IMO) was set up as a collaboration between University College London, YuTAKE, the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan and the Institute for the History of Material Culture, St. Petersburg.

The oasis of Merv has been inhabited at least since Neolithic times, and the oldest urban settlement that can be found within it is the site of Erk Kala, which has been dated to the VI century BCE, coinciding with the annexation of the area into the Achaemenid empire, or perhaps its predecessor the Median empire. Merv, or Margiana, is quoted in the great inscription of Darius I at Bīsotūn near Kermanshah in Iran as part of his empire, included in the great satrapy of Bactria. The next step in the urban development of Merv was the foundation by the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter (281-261 BCE) or the Greek metropolis of Antiochia in Margiana; of which the ancient city at Erk Kala became its citadel. The site occupied by the new Seleucid city at the foot of the Erk Kala citadel is known nowadays as Gyaur Kala.

Satellite view of the ancient city of Marv. The poligonal structure in the upper part of the picture is the Erk Kala citadel; and the part surrounded by a roughly square ruined wall is the lower city (Gyaur Kala). The main gates and the main roads that quartered the city can still be seen in this image (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

Artist's reconstruction of the ancient city of Marv from the southeastern corner of the city, with the Buddhist stupa in first term.

Aerial view of the Erk Kala citadel, seen from the northwest.

This was to become later the Arsacid and Sasanian city of Marv. It was located in the east central part of the oasis and lies next to the Razik canal; the main channel of the river Murghab flows much further to the west. At first sight, he site is dominated by the massive remains of the polygonal citadel at Erk-Kala which towers over a roughly square lower city (Gyaur Kala) which measures 2 km across; together they cover an area of some 374 ha. Each was encased within massive fortifications consisting of hollow curtains with external plastered glacises, which were constructed during the Sasanian period above the solid in-filled remains of earlier fortifications (Seleucid and Arsacid). The bulk of the built environment within the city connected the main east and west gates in a rectangle covering an approximate area of 125 ha. Additional residential quarters sprawled towards the south and north gates and added an additional 28 ha. or so to the built-up area. Each of these gates was situated midway along the curtain except on the north side where the central position of the citadel meant that the gate on this side was off-center, positioned directly to the east and commanded by a bastion of the citadel. It can be deduced from their morphology that all of the gates possessed a projecting outer wall and were approached by a ramp running parallel to the curtain. The curtain walls had towers at regular intervals, and excavations next to the southwest corner bastion revealed a sequence of redesign, constant use and strengthening of the fortifications during the four centuries of Sasanian rule. A fifth gate was situated on the western wall but bypassed the residential quarters and led into an open area on the western side of the citadel. Archaeologists believe that this area within the walls was substantially unoccupied in antiquity for a reason. Given the existence of the separate gate, it seems most likely that this area was limited to official and military activity, used for drilling and providing space for the horses which made up an essential part of the Sasanian army. In any case, its location suggests it was limited to military and official activity.

Evolution of the walls that surrounded Gyaur Kala across the centuries.

1. Seleucid wall, built around 280 BCE.

2. Arsacid wall, around II century CE.

3. Late Arsacid wall, around I century CE.

4. All phases put together.

A. Filled-on access gallery.

B. Arrow slit.

C. Outher defenses.

D. Erosion debris.

2. Arsacid wall, around II century CE.

3. Late Arsacid wall, around I century CE.

4. All phases put together.

A. Filled-on access gallery.

B. Arrow slit.

C. Outher defenses.

D. Erosion debris.

Hypothetic reconstruction of the walls around the Sasanian city of Marv.

Apart from the main city of Marv, other smaller forts dotted the oasis; the whole complex, would become the main eastern stronghold of the Arsacid and Sasanian empires against their eastern enemies (Kushans, Huns and Turks). One of the most important mints of the empire was located here, in order to pay its large garrison and the large armies that the Sasanian kings assembled there for their eastern campaigns. At this time, it was almost assuredly under the direct rule of the Šāhān Šāh, and due to its strategic situation and its imposing fortifications, it was the main military base for the Sasanian spāh during any campaign in Central Asia. In short, the oasis of Merv had a key strategic importance both for defending the exposed north-eastern border of the empire against Central Asian invaders and to block them entry into the Iranian Plateau and the heart of Ērānšahr, but also for projecting Sasanian military power into Bactria, Sogdia and beyond.

Archaeologists have identified up to 162 settlements dated to the Sasanian period within the oasis; as well as a complex irrigation network that was mostly built in Arsacid times. Of these settlements, a total of 133 sites covered an area of less than 4 ha., therefore falling within the category of village or hamlets according to Sasanian standards; an additional 17 sites covered areas of up to 30 ha. and thus, may be regarded as equivalent in size to a town, but only three exceeded that. To archaeologists, this must imply a high level of rural development in the hinterland of the city of Marv, with a cluster of settlements along the course of the Murghab, as well as along canals flowing due north. Many of these Sasanian settlements appear to have been built on artificial platforms (dakhma) raised above the alluvial plain and surrounded by ditches and moats. Archaeological digs at two of these raised mounds (called kalas and tepes in the local Turkic language) at Göbekli-tepe and Chilburj have revealed that they were substantially fortified, with walls and towers that were rebuilt and reinforced during Sasanian rule.

Plan of the remains of the settlement at Göbekli-tepe (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

The case of Chilburj is particularly interesting. Soviet excavations in 1980 dated the present remains to the V century CE, although it seems to have an Arsacid origin. The main portion of the settlement consists of an almost square site covering some 2.7 ha. and surrounded by a hollow curtain wall with square projecting interval towers. It had a heavily defended gatehouse on the southern side, a similar construction on the north side which was presumably blocked at a later date (perhaps in a moment of siege or military crisis), and elongated corner towers which were probably designed to enable torsion artillery to block access to the gates in case of a siege. And the case of the fort at Chilburj is not the only one in the oasis of Merv.

Archaeological drawing and aerial photograph of the remains of the Sasanian fort at Chilburj in the Merv oasis (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

Another typology of fort is found at Durnali, rectangular in shape, with regularly placed square towers projecting from the wall, while the area within the walls was divided by rectilinear streets and alleys in an orderly fashion; immediately to the south of the fort, archaeologists have found an extramural settlement of some 7 ha. which has been dated to the late V to VII centuries CE. A third typology appears at the northern edge of the site of Köne Kishman; in here archaeologists were puzzled by the fact that apparently the enclosed space within the walls lacks any trace of occupation. One possible explanation for this is that it was a campaign fort which originally enclosed rows of tents rather than permanent barracks, in a similar way to the forts that have been excavated along the Gorgan Wall further to the west. This strongly suggests that the whole oasis was provided at some point in time with an array of fortified spaces designed to lodge a large campaign army with plenty of space within their walls, as would befit a cavalry-heavy army. Apart from its commercial and agricultural importance, the Merv oasis was a huge military basis for the Sasanian spāh and the main jumping post for its campaigns in Central Asia, both in Sogdia to the north and Bactria to the east.

Archaeological drawing and aerial photograph of the remains of the Sasanian fort at Durnali in the Merv oasis (according to the British archaeologist St. John Simpson).

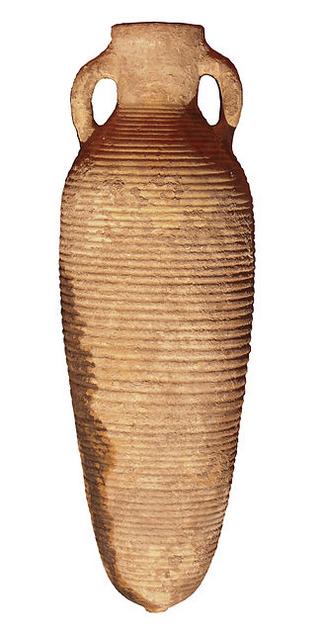

The archaeological evidence therefore suggests a militarized yet prosperous pattern of settlement in the oasis with a high density of settlements of different sizes, some walled and some apparently unwalled, with the largest center being the city of Marv itself. Literary sources consistently praise the rich agricultural resources of the Merv oasis during the Classical and Islamic periods. Although equivalent written sources are lacking for the Sasanian period, archaeologists think it’s reasonable to extrapolate a similar situation for Sasanian times, and there is evidence for major canal off-takes from the river Murghab at this period. An important find in the oasis of Merv was the discovery of large quantities of accidentally carbonized cotton seeds in contexts dating from the IV century CE onwards, which provides the earliest archaeobotanical evidence for cultivation of this fiber crop in the oasis and contradicts the hypothesis that cotton cultivation was introduced as late as the IX century CE.

The population of the oasis before it became Turkicized during the late Middle Age was formed by Iranian speakers, who probably spoke originally a dialect of Parthian; the use of Parthian in written form is attested still in the IV century CE. When the city surrendered to the armies of the Rashidun Caliphate in 651 CE, the population of the city and the oasis was predominantly Zoroastrian, but the city also hosted large and vital Manichean, Jewish, Nestorian Christian and Buddhist communities, with a large Buddhist monastery and stupa occupying the southeast corner of the city. The oasis of Merv was controlled by the Sasanian dynasty since the times of Ardaxšir I until the Islamic conquest, being only lost for a short timespan to the Hephtalites during the late V and early VI centuries CE; scholars are quite sure of this because all the Sasanian kings minted coins here except for the aforementioned time period.

Last edited: