7.8 THE SOGDIAN LANDS.

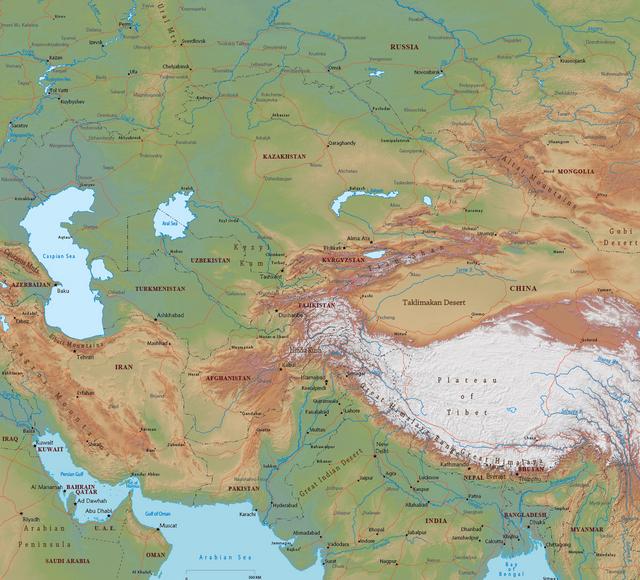

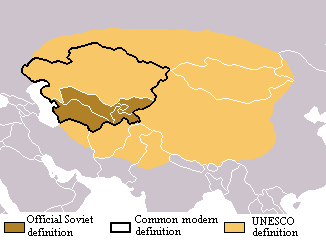

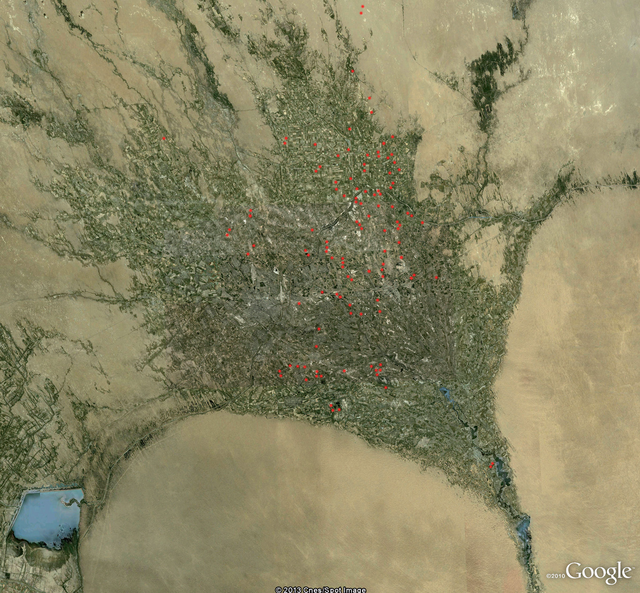

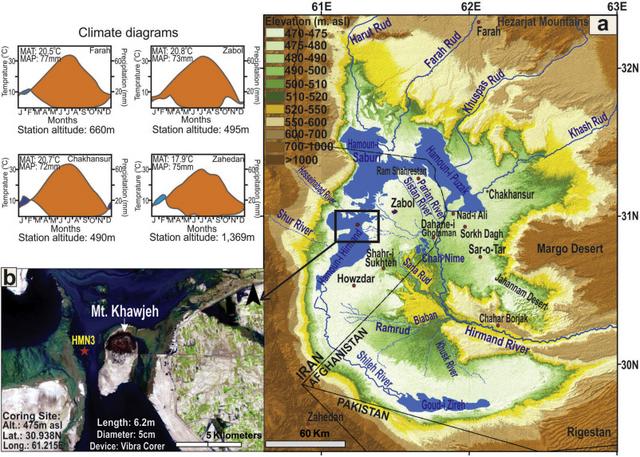

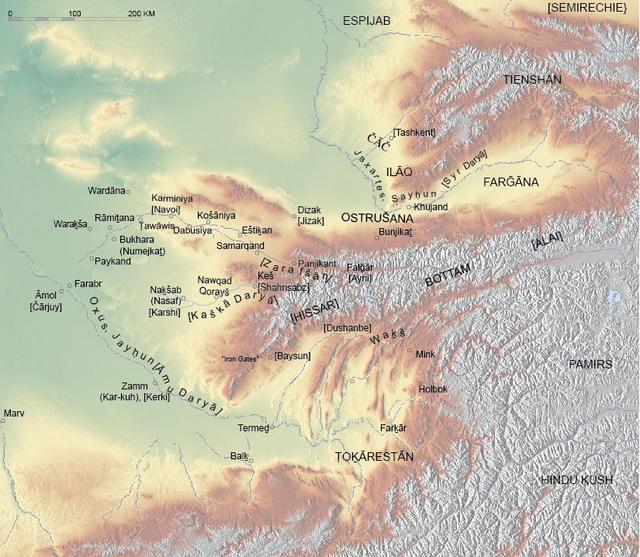

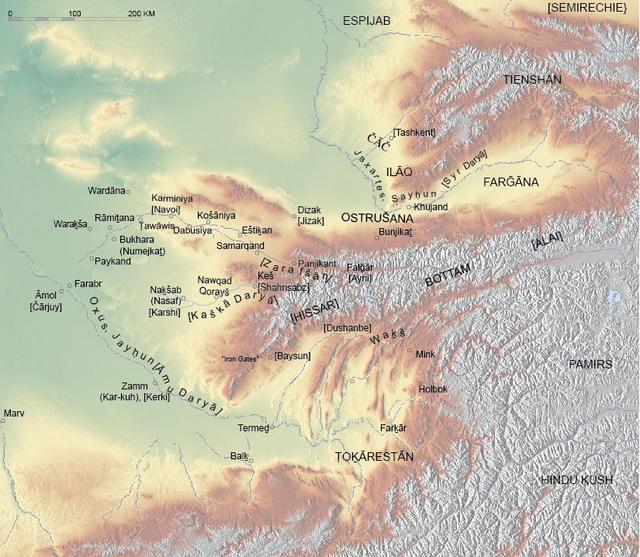

Sogdiana (or Sogdia) was an Iranian-speaking region in Central Asia that stretched from the rivers Āmu Daryā in the south to the Syr Daryā in the north, with its heart in the valleys of the Zarafšān and the Kaškā Daryā rivers. But its exact borders varied along time; Classical sources offer at times very confused descriptions and it’s difficult to reconstruct from them what was the exact extent of Sogdiana according to Greek and Roman geographers. Chinese descriptions (especially from the III-IV centuries CE onwards) are very detailed and give us quite precise limits; apparently the Chinese between the III and VIII centuries considered “Sogdiana” to include even Khwārazm and all the steppe south of the Issyk Kul Lake, which is a staggeringly large extension of territory. By far, the most precise descriptions have been left by Muslim authors of the first Islamic centuries writing in New Persian and Arabic; but the territory that they considered to be “Sogdiana” was surprisingly small: just the valley of the Zarafšān River between Samarkand and Bukhara.

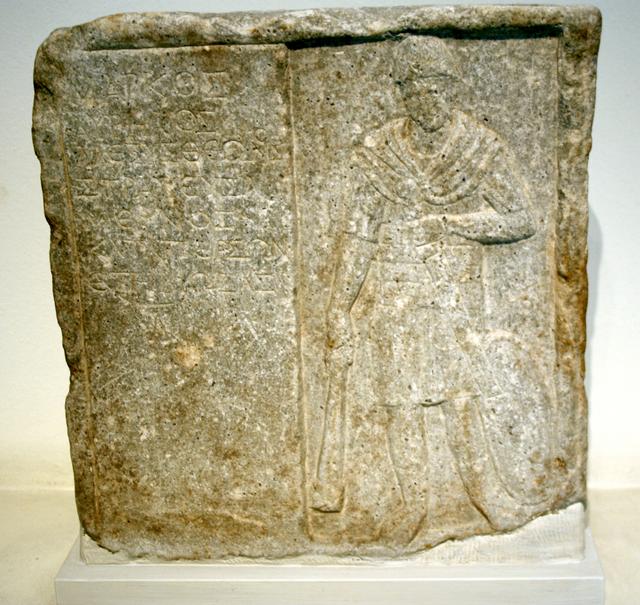

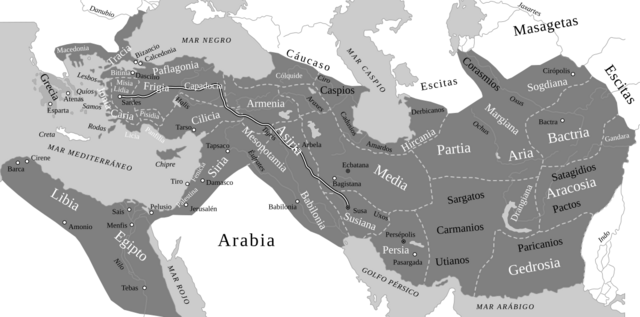

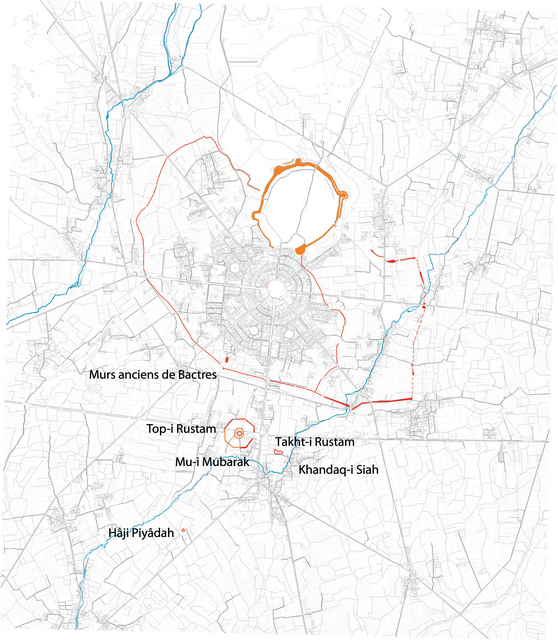

Map of ancient Sogdiana, with most of the cities and geographical names quoted in the text.

Here I will consider as “Sogdiana” the territories that are usually considered so by the current academic consensus, and I will deal also with the territories to the north of Sogdiana proper (the Ferghana Valley and the Tashkent oasis) that were historically part of the Sogdian cultural sphere.

The description is complicated by the fact that these territories are divided today between four states: Uzbekistan (which includes most of the area, plus its two historically largest cities: Samarkand and Bukhara), Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The limit that is clearest is the southern one: ancient Sogdiana was located in its entirety to the north of the Oxus (modern Āmu Daryā). The southeastern limit with Bactria though is tricky. Originally, the limit between Sogdiana and Bactria was the valley of the Surkhan Daryā, until it joined the Āmu Daryā at Termeḏ. But at some time under the Graeco-Bactrian kings or the early Kushans, the border was moved to the east to the Hissar Range (also spelled

Hissor or

Gissor) and Termeḏ became a Bactrian city.

To the east, ancient Sogdiana becomes a very rugged country, and it’s difficult to establish with any clarity where stood its ancient limits. In this part of the country, three mountain ranges run parallel to each other on an east to west direction, as extensions of the great Pamir Range. The Hissar Range runs parallel to the south of the Zarafšān Range before it turns south and gradually ends before meeting the Āmu Daryā. To the west of Lake Iskanderkul, the Zarafšān Range and the Hissar Range are connected by the Fann Mountains, which form the highest part of both ranges. The eastern and southern escarpments of the Hissar Range (whose rivers were direct tributaries of the Āmu Daryā in its upper valley) belonged to Bactria in Antiquity, while the opposite escarpments belonged to Sogdiana. The so-called Pass of the Iron Gates across the western part of the Hissar Range was the border point at which the main caravan road between Balḵ and Samarkand (via Termeḏ) crossed from Bactria into Sogdiana.

The Anzob Pass in the Hissar Range, with the Zarafšān Range in the background.

The Zarafšān Range extends over 370 km in an east−west direction, reaching the highest point of 5,489 m at Chimtarga Peak in its central part. South-west of the town of Panjakent the range crosses from Tajikistan into Uzbekistan, where it continues at decreasing elevations (1,500–2,000 m), until it blends into the desert southwest of Samarkand. To the north, the valley of the Zarafšān River runs east for approximately 250 km from Samarkand and separates the Zarafšān Range from the Turkestan Mountains, and then it runs parallel to its north.

The upper valley of the Zarafšān River.

The Zarafšān Range is crossed in a north-south direction by three rivers: the Fan Daryā, the Kaštutu Daryā, and the Maghian Daryā, all of which flow north and are left tributaries of the Zarafšān River. The part of the Zarafšān Range east of the Fan Daryā is also known as the Matcha Range. It has heights around 5,000 m and in the east, it’s connected to the Alay Range, which is the third of the parallel ranges that I mentioned earlier in this text. The Matcha Range is the location of the Zarafšān Glacier, which is 24.75 km long and is one of the longest glaciers of Central Asia. The northern slopes of the Matcha Range are relatively smooth and slope gently to the Zarafšān River, whereas the southern slopes drop sharply to the valley of the Yaghnob River.

The highest part of the Zarafšān Range is located between the Fan Daryā and the Kaštutu Daryā and includes the Fann Mountains. The western part of the range reached heights of up to 3,000 m and is heavily forested. There are several passes crossing the range, including Akhba-Tavastfin, Akhba-Bevut, Akhba-Guzun, Akhba-Surkltat, the Darkh Pass, Minora, and Marda-Kishtigeh, with elevations between 3,550 and 5,600 m. The Fan Daryā has also excavated a gorge across the range. These ranges are rich in minerals such as coal, iron, gold, aluminum and sulphur. Gold findings have been reported for the entire course of the Fan Daryā, Kaštutu Daryā, and Maghian Daryā, and it provides the etymological root for

Zarafšān, which means “spreader of gold” in New Persian. This mountainous part of Sogdiana is included today mostly within Tajikistan, and most of its population is still Iranian-speaking (the main spoken language is Tadjik, which is how the local variant of New Persian is called in Tajikistan for political reasons). Although the Sogdian language is now extinct, there is a small population in the valley of the Yaghnob River who speak Yaghnobi, an Eastern Iranian language that is considered by linguists to be a descend directly from Sogdian.

The Fann Mountains.

The two vital rivers for the ancient Sogdian economy are born in these ranges: the Zarafšān and Kaškā rivers; I will come back to them later when I describe the lowlands of Sogdiana proper, but now to keep some sort of geographical order, I will continue this trip north. North of the Turkestan Mountains we find the upper valley of the Syr Daryā, the other great Central Asian river. This is the Fergana Valley, which has been historically one of the most fertile places in Central Asia.

The Turkestan Mountains (confusingly named similarly as another east-west range in northern Afghanistan) are an extension to the west of the Alay Range, which is itself just an extension of the great mountain range of the Tian Shan that borders the Tarim Basin to the north. The Central Tian Shan Range is separated from the Alay Range by the valley of the Kara Daryā River; to the north-west of this valley, the Fergana Range forms the eastern limit of the Fergana Valley, and is separated from the Chalkal and Kuramin ranges that forms the northern enclosure of the Fergana Valley by the valley of the Narin River.

Map of the Ferghana Valley showing the modern political boundaries that cross it between the Central Asian republics of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

The Narin and Kara Daryā rivers met within the valley near the Uzbek city of Namangan and form the Syr Daryā at their confluence. Almost all of these mountain ranges that surround the Fergana Valley fall within the limits of the modern state of Kyrgyzstan, while the lower parts of the valley are divided between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The Fergana Valley is about 300 km long and up to 70 km wide, covering an area of 22,000 km2. The valley owes its fertility to the numerous rivers that flow across it; apart from the Narin, Kara Daryā and Syr Daryā, several other tributaries of these rivers exist in the valley, like the Sokh River that flows from the Turkestan Mountains to the south. All these rivers, and their numerous mountain tributaries, not only supply water for irrigation, but also bring down vast quantities of sand, which is deposited along their courses, especially along the banks of the Syr Daryā where it cuts its way through the Khujand-Ajar ridge at the western entry of the valley. This creates wide expanses of quicksand that cover an area of 1,900 km2 and which, under the influence of south-west winds, encroach upon the agricultural districts.

The Kara Daryā River near Namangan.

The oasis of Tashkent is located on the course of the Chirchiq River, a tributary of the Syr Daryā on its northern bank, about 60 km to the northeast of the confluence between both rivers, and at about the same distance to the northwest of the entry of the Ferghana Valley. In ancient times, this oasis was the center of the principality of

Čāč, and the northernmost settlement in the Sogdian periphery, except for some “colonies” that Sogdian nobles built even more to the north, on the northern piedmont of the Chalkal and Kirghiz ranges, all the way to near the Issyk-Kul Lake, on the northern slopes of the Tian Shan mountains.

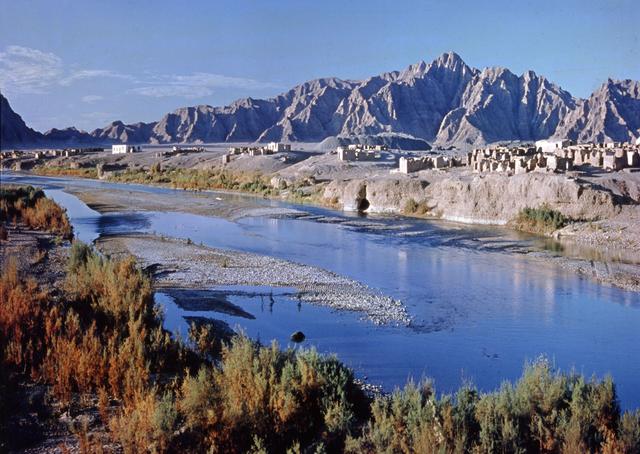

Back to the south, Sogdiana “proper” can be defined as the territory enclosed by the wide bend of the Zarafšān River (formerly also called the

Soğd River, and the

Polytimetus River by the Greeks) as it leaves its upper valley deeply enclosed between the parallel Zarafšān and Turkestan ranges and turns slightly to the northwest and then describes a wide bend to the southwest before ending in two large consecutive alluvial fans before reaching the Āmu Daryā; these two alluvial fans form two large oasis (similar to those in Merv and Balḵ) that are (in downstream order) the Bukhara oasis and the Qaraqul oasis. Along the middle and lower valley of the Zarafšān River lay most of the largest Sogdian cities, especially the two largest and most famous ones: Samarkand and Bukhara. The Kaškā Daryā springs in the Hissar Range south of the Zarafšān River, and carries much less water, it’s also much shorter. It eventually vanishes into the Qarshi Steppe, well within the wide bend of the lower Zarafšān valley. In its banks stood some important Sogdian settlements, especially the city of

Naḵšab (also referred to as

Nasaf, corresponding to the modern Uzbek town of Karshi).

The upper valley of the Kaškā Daryā.

To the northwest of the lower valley of the Zarafšān River, there’s the inhabited expanses of the Kyzyl-Kum (“red sands” in Turkic) Desert, which occupies all the territory between the Āmu Daryā and Syr Daryā until the Aral Sea.

Before the arrival of Iranian-speaking peoples in Central Asia, Sogdiana had already witnessed at least two urban phases. The first one was centered at Sarazm (fourth to third millennia BCE), where a town of some 100 ha has been excavated and where both irrigation agriculture and metallurgy were practiced. The second phase began towards the XV century BCE at Kök Tepe, on the Bulungur canal north of the Zarafšān River, where the earliest archeological material appears to go back to the Bronze Age, and which continued throughout the Iron Age, until the arrival from the north of the Iranian-speaking populations that were to become the Sogdian people. This urban settlement declined with the rise of Samarkand. Pre-Achaemenid Sogdiana is mentioned in the Younger Avesta (

Vendīdād, 1.4;

Yašt 10.14; the name of Sogdian lands in the Avesta is

Gauua) and is said to be inhabited by “the Sogdians”.

Cyrus the Great conquered Sogdiana in about 540 BCE. He advanced as far as the Syr Daryā, where he established the town of

Kyrèschata (known as

Cyropolis by the Greeks), the farthest extent of the Achaemenid empire to the northeast, identified with the current site of Kurkath. Samarkand probably received its first major fortifications during this period. Sogdiana was integrated into the Achaemenid empire as a distant frontier province and remained as such until the arrival of Alexander the Great in 329 BCE. No satrap for Sogdiana is known, and the recently discovered Aramaic documents from Bactria confirm that Sogdiana was governed from Bactra. The region provided contingents of soldiers to the Achaemenid kings, along with laborers and semiprecious stones (lapis lazuli and carnelian or garnet) for the palace workshops. Deported populations from other parts of the Achaemenid empire were often settled there. The influence of the Achaemenid empire had lasting effects in the region; more than a millennium after its fall, in the VII century CE, the administrative

formulae inherited from Babylonia were still in use in Sogdiana. Around the beginning of the Common Era, the Sogdian script was developed out of the Aramaic alphabet brought into Sogdiana by the Achaemenid bureaucracy; with the exception of the script of Bukhara, which remained very similar to Arsacid Pahlavi.

At the time, Sogdiana constituted the northern frontier of the sedentary world and was in constant contact with the nomads of the steppe. Sogdian society was an agricultural one based on the irrigation of the fertile loess soil of the Zarafšān and Kaškā Daryā valleys. Large-scale irrigation may go as far back in time as the second millennium BCE. The nomads built their kurgans around the settled oases occupied by the sedentary Sogdians and their economic exchanges, products of animal husbandry for products of the earth, seem to have been significant. This constant interaction and coexistence of the agricultural, sedentary Sogdians with the steppe nomads within the same geographical area was to become the dominant feature of Sogdian economic and political life from Antiquity to the Mongol invasions.

It took three years for Alexander of Macedon to subdue Sogdiana; the

diadochi who succeeded him kept control of the region until 247 BCE. Afterwards, the Graeco-Bactrian rulers, who were descendants of local Greek colonists, asserted their independence and, according to numismatic evidence, they apparently held control over most of Sogdiana until approximately 140 - 130 BCE. The Greeks provided Sogdiana with its first real coinage, because Achaemenid silver darics are almost entirely absent from the area. Certain types of Greek coins remained in use in Sogdiana in degraded form until the V century CE. Archeological digs have revealed that the walls of Samarkand show clear signs of Greek rebuilding, and millet granaries for the Greek garrison have been found on the acropolis/citadel.

The next five hundred years of Sogdian history are extremely obscure. There is basically no information on Sogdiana concerning this period other than what is related in the Chinese sources (

Shiji,

Hanshu and

Hou Hanshu). Around 160 - 130 BCE, the region was overrun by various waves of migratory nomads from the north, first by the Iranian-speaking Saka followed by the Yuezhi who had been displaced by the Xiongnu from near the Chinese northeastern borders. Beginning in the I century BCE, most of Sogdiana was included in a larger nomadic state, centered on the middle Syr Daryā that is named by the Chinese sources as

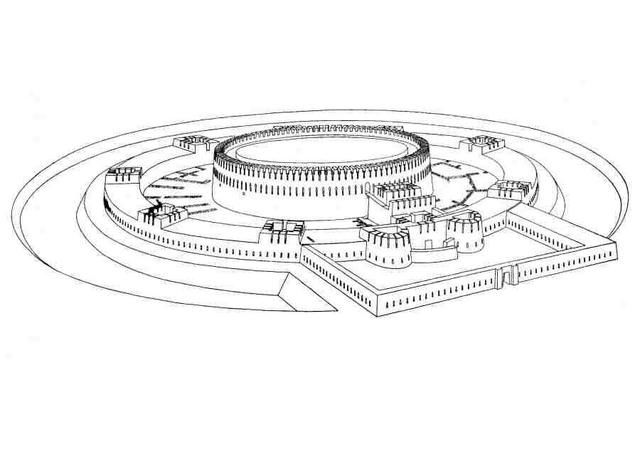

Kangju; based on the scanty evidence available modern scholars consider the Kangju to have been of Iranian stock. On the other hand, the Yuezhi principalities and then the Kushan empire incorporated the southeast part of Sogdiana (south of the Hissar mountains), which thereafter left the Sogdian sphere and was attached to Bactria. Small-scale Sogdian commerce then developed in imitation of the larger-ranging merchants operating farther south, in Bactria; these were the humble beginnings of a commercial tradition that would come to dominate Eurasian exchanges during Late Antiquity. The economic activity seems to have been limited to agriculture, while artistic activity has been deemed "rather mediocre" by the French scholar Frantz Grenet. Archaeologically, the Kangju state has been tentatively linked to the appearance of the culture of Kaunchi (which stretched from the II century BCE to the VIII century CE), named after the site (Kaunchi Tepe) on the middle valley of the Syr Daryā where most of its artifacts have been found. And some archaeologists have suggested that the capital of this state could have been at the site of Kanka, to the south of Tashkent, where in the first centuries of the Common Era a city was laid out according to a rectilinear square plan and was surrounded by a wall with internal corridors occupying a total surface of 150 ha. This culture seems to have developed from nomadic populations native to the land, as it shows the coexistence of towns, cities and non-irrigated agriculture with cultural practices associated to nomadic steppe cultures, like kurgan burials.

According to the

Shiji,

Hanshu and

Hou Hanshu, the Kangju state at one point managed to control a very large territory in Central Asia. The first notice in the Chinese sources of the Kangju can be found in the

Shiji. They were mentioned by the Chinese envoy and diplomat Zhang Qian who visited the area ca. 128 BCE, and whose travels were included in the

Shiji (whose author, Sima Qian, died ca. 90 BCE):

Kangju is situated some 2,000 li (i.e. 832 km) northwest of Dayuan (i.e. the Fergana Valley). Its people are nomads and resemble the Yuezhi (i.e. the nomad people from which the Kushan dynasty would eventually emerge) in their customs. They have 80,000 or 90,000 skilled archers. The country is small, and borders Dayuan. It acknowledges sovereignty to the Yuezhi people in the South and the Xiongnu in the East.

According to the account in the

Shiji, Zhang Qian also visited a land known to the Chinese as

Yancai (literally meaning "vast steppe"), which lay north-west of the Kangju and whose people were said to resemble the Kangju in their customs. some scholars have identified the Yancai with the

Aorsi,

Aorsoi or

Aiorsoi of Graeco-Roman sources, living in the vicinity of the Aral Sea.

According to the

Hanshu (which covers the rule of the earlier or western Han from 206 BCE to 23 CE), Kangju had expanded considerably to a nation of some 600,000 individuals, with 120,000 men able to bear arms. Kangju had become now a major power in its own right, and by this time it had gained control of Dayuan and Sogdiana in which it controlled “five lesser kings”. Another interesting information to be found in the

Hanshu, is that in 101 BCE the Kangju had allied with the people of Dayuan (Fergana) and provided them with help against the armies of the Han empire which had started to cross the Pamirs from the Tarim Basin.

At the beginning of the 1980s, a bone plaque (probably part of a belt) was discovered in the Uzbek site of Orlat, 50 km northwest of Samarkand. Although their its exact dating is still in dispute, some scholars think that they should be dated to the Kangju era, while others are more inclined towards a dater, Hunnic dat (IV - V centuries CE). All agree though, that this plaque does not reflect Sogdian artistic traditions, but those proper to steppe peoples, and so that they were brought to the place where they were found by northern nomads.

The apogee of Kangju power though seems to have happened during the rule of the later or eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220 CE). According to the

Hou Hanshu (

Chronicle of the Later Han, redacted in the V century CE) at that time

Suyi (i.e. Sogdiana), and both the "old"

Yancai (which had changed their name to

Alanliao and seem here to have expanded their territory to the Caspian Sea), and

Yan, a country to Yancai's north, as well as the strategic city of "Northern Wuyi" (considered by scholars to be the Alexandrine foundation of

Alexandria Eschate in the Fergana Valley, which has been tentatively identified to the modern Tadjik city of Khujand), were all dependent on Kangju. These data from the

Hou Hanshu have led to many speculations by scholars: some of them have linked the name

Alanliao with the Sarmatian

Alani, and their subjugation by the Kangju with their migration west to the Pontic Steppe where they entered in contact with the Roman-controlled Greek settlements on the northern coast of the Black Sea and the Roman client kingdom of the Bosphorus, and eventually launched attacks across the western Caucasus and through Armenian territory into the Roman provinces of

Bithynia et Pontus and Cappadocia, where they were defeated by the provincial garrison led by its governor

Lucius Flavius Arrianus (Arrian of Nicomedia), which has left us a detailed account of his order of battle when fighting the Alani in his

Ektaxis kata Alanon, which can be translated into English as “Deployment against the Alani” or “Order of battle against the Alani”.

According to these Chinese sources, the Kangju sustained a long rivalry against their nomadic northern neighbors the

Wusun (which according to Étienne de la Vaissière were another Iranian people) and became embroiled in the wars between the Xiongnu and the Han, whose main theater was located much farther to the east but which also spilled into western Turkestan after the Han conquest of the Tarim Basin and the encroachment of Chinese armies into the Fergana Valley, a conflict that eventually led to the intervention of the Kushan empire further to the south as well.

The "Westrn Regions" according to the Shiji, the Hanshu and the Hou Hanshu.

The Kangju state appears to have devolved in the II-III centuries CE into a confederation and Chinese sources mention the petty kingdoms that formed it. This “confederation” should be interpreted as aristocrats of Kangju nomadic stock being in charge of the territories centered around each of the large cities of the old unified kingdom, which were inhabited by people who were not “ethnically” Kangju, but Sogdians or members of other cultures. This confederate organization has recently been confirmed with the discovery at the site of Kultobe in the Arys River valley in Kazakhstan of a dedicatory Sogdian inscription, dated to the II - III centuries CE, in the remains of a fortified city alluding to the foundation of the city as a joint “colonial” enterprise by the main city-states of Sogdiana (Čāč, Samarkand, Keš, Naḵšab and Bukhara) encroaching upon the territory of the

Wusun nomads that inhabited this area.

The Chinese sources of the IV to VIII centuries CE give very detailed descriptions of Sogdiana and attest to the very close links between it and China, where colonies of Sogdian traders are already attested during the early IV century CE. The Chinese perceived Sogdiana not as a unitary state but rather as a federation of cantons of

Hu barbarians (i.e., a settled Iranian population), which were governed by princes of the

Zhaowu clan. The most important ruler resided in Samarkand, which was named

Kang and was considered by the Chinese to be a continuation of the ancient Kangju state. Other lands of the “

Hu of nine houses of

Zhaowu” were also given one-syllable names: so Māymorḡ (to the east of Samarkand, perhaps including Panjikant) was called

Mi; Osrušana (also transliterated as

Ustrushana; the region of Ura-tyube in Uzbekistan to the southwest of the Fergana Valley), the northern part of the Samarkand oasis and its northwestern part around Eštikan were called

Cao (in turn divided into eastern, central and western respectively); further west, around Karminiya and modern Navoi, on the middle Zarafšān, the Chinese located the territory of

He; the Bukhara oasis was called

An (probably after ancient

Anxi; which was the transcription of

Aršak, meaning “Parthia”), and the upper part of the Bukhara oasis was the “Lesser

An”; Paykend was

Bi; Keš on the Kaškā Daryā was

Shi and Naḵšab downriver from Keš was called Minor

Shi.

From the III century CE onwards, the presence of Sogdian merchants and artisans increased in China, to the point that in the large cities they formed communities that were led by their own leader, the Sabao as it was known in Chinese. Several tombs of these sabaos have been found in China; in 2003 the tomb of the Sogdian trader Wirkak was found near Xi'an in central China. The epitaph is bilingual, in Sogdian and Chinese, and describes his whole life since his youth in the Sogdian state of Shi until his rise to the post of sabao of the Sogdian community in Wuwei. He died in China in 579 CE and his sons buried him and his wife Wiyusi (also a Sogdian, from the state of Kang) according to the Sogdian Zoroastrian custom, in a grave adorned with sculpted reliefs. This is the south (front) side of his sarcophagus.

These one-syllable denominations were also applied by the imperial administration as surnames of Sogdians (“Hu”), who lived in China and are attested even in Sogdian texts composed in the Far East. The territories adjoining Sogdiana, namely

Shi (Čāč),

Mu or

Wu-di (Āmol, modern Čārjuy on the Āmu Daryā),

Wu-na-he (modern Kerki on the Āmu Daryā) and

Huoxin (Khwarāzm) were also sometimes included in the

Zhaowu confederation according to the Chinese histories. In the travel-report of Xuanzang, who passed through Central Asia in 630 CE, all the territory between

Suye (Suyāb in the Ču valley, to the East of modern Bishkek in Kyrgyzstan) and the “Iron Gates” mountain pass between Keš and Termeḏ is called

Suli, and he said that they shared the same language and culture. The Chinese records of this time supply us also with transcriptions of a number of local place-names (mostly identifiable ones), reliable accounts on distances between cities, descriptions of rivers, mountains, remarks on the economy, religions of Sogdian lands and their political organization (including the names of a number of rulers and their embassies to the imperial court). The “houses of

Zhaowu”, that is, the minor principalities of Sogdiana, had a certain degree of independence and some of them at least had their own coinage.

At the end of the

Kangju period, urban hierarchies had developed in Sogdiana. In the south in the valley of Kaškā Daryā, Naḵšab had achieved a dominant status, while in the north near the Syr Daryā the town of Kanka (located within the district of Čāč, near modern Tashkent) played the same role. On the other side, Samarkand was reduced to a third of the area of 220 ha that it had occupied during the Greek period, and the oasis of Bukhara no longer seems to have been organized around a dominant central town, although the town of Paykend seems to have been already in existence.

Scholars don’t know how to interpret Šābuhr I’s ŠKZ inscription, which gives the limits of his empire as

Keš,

Suğd,

Čāč; this has been interpreted by Étienne de la Vaissière as a confirmation that the Sogdian cultural area was still divided amongst several principalities. That means that all of Sogdiana, including its northern peripheries all the way to the oasis of Tashkent, were under Šābuhr I’s rule. The problem is that this claim is rather dubious, as there’s no archaeological or numismatic evidence of Sasanian presence north of the Āmu Daryā during the III and IV centuries CE: neither buildings, nor reliefs, coins or any other sort of artifacts. This has led some scholars to consider Šābuhr I’s claim as a mere empty claim to rule over all the lands that had been once ruled by the greatest of the Kushan emperors Kanishka I, and by others to indicate just that he exerted some sort of protectorate over the Sogdian principalities, which were tributaries of the Sasanian kings, but that there were no Sasanian troops or bureaucracy north of the Oxus. On the other side, it’s interesting to note that Ammianus Marcellinus expressly named the

Sogdiani as one of the peoples that formed part of Šābuhr II’s empire.

Samarkand is perhaps the most famous of the cities of ancient Sogdiana; it stands in the middle valley of the Zarafšān River, in a hilly countryside that is the last western projection of the Zarafšān and Turkmenistan mountain ranges. The French archaeologist and historian Étienne de la Vaissière wrote an interesting study about traditional irrigated agricultural systems in this site in order to make a very broad estimate of the demographic capabilities of the area (in the same paper where he accrued out similar studies for the alluvial oasis of Merv and Balḵ that I quoted in earlier posts), and I will quote now in some length.

Irrigation canals and irrigated croplands in Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages in the middle Zarafšān valley, according to Étienne de la Vaissière.

The structure of irrigation in the middle Zarafšān valley and in Samarkand was very different from the ones at Merv and Balḵ This is a valley, not an alluvial fan, and here the water flows naturally along its lowest topographical point. The aim of irrigation is to manage to keep the water as high as possible, by carefully designed side canals starting as upstream as possible and with a slope as reduced as possible. Except for the upper reaches of these canals, the so-called idle part useful only for allowing the canal to reach a controlled topographical height, every single plot of land between the canal and the bottom of the valley could theoretically be irrigated. The crucial part is then the date of the several canals irrigating the valley. De la Vaissière was certain, because of the map of the Early Middle Ages settlements, that the Bulungur, Dargom and Yangi Ariq canals were flowing, and that the Miankal, the wet zone between two branches of the Zarafšān River, was drained. De la Vaissière also believed that further downstream the Faiy area was also watered, but he’s not as sure about the Narpay and the Eskiangar canals. The zone that can be irrigated by the Eskiangar canal was not settled, according archaeology: it was watered in Antiquity and it would also be irrigated later in the Timurid period, but not in-between. As for the Narpay canal, that today irrigates the Chilek region, De la Vaissière was quite sure that it did not exist during Late Antiquity, as the Arab geographer Ibn Ḥawqal described the Widhar-Chilek region as watered by rain and streams, not irrigated.

With these data, De la Vaissière estimated the irrigated part of the middle valley of the Zarafšān, from Waraghsar to the entrance of the Bukhara oasis to cover about 3,500 km2. De la Vaissière concludes that if all this land was annually irrigated, which was perfectly possible as water is usually plentiful in the area, then around 750,000 people could have been fed with grain only.

De la Vaissière though points out that this is rather a maximum than a minimum, based on the idea that all the available land within canals was watered, something that in actual history would only have been true during limited, peaceful periods. However, De la Vaissière also points out that even if we wanted to cut down this number, we should also increase it: to wheat fields we should also add orchards which can sustain ca. 600 p./km2, dairy products from pastoralism and also the wheat fields in the lateral zones of the valley, watered only with local water sources and rain. According to De la Vaissière, these pluvial agriculture zones were actually very extensive and cover around 1,500 km2. According to one early Islamic source (left unnamed by De la Vaissière) when the weather was favorable, the yield of Abghar, a 700 km2 region of pluvial agriculture (before and after this time irrigated in part by the Eskiangar canal) could be over 1:100 and feed the whole

Suğd, i.e. the region between the oases of Bukhara and Samarkand. De la Vaissière stated that even if this was an exaggeration, it still points to very productive agricultural zones to be added to the 3,500 km2 irrigated region. However, De la Vaissière decided to calculate according to an average rate: in medieval Iran the taxes of pluvial agriculture lands were 1/3 of the taxes on irrigated land. Translated into what De la Vaissière calls “feeding power”, these lands would be equivalent to triennial fallow lands which could support about 70 p./km2, this would add about 100,000 inhabitants to the grand total who could possibly be fed by the agricultural resources of the valley. This would put more firmly the population of the middle valley of the Zarafšān close to 700,000 or 800,000 inhabitants, as a middle hypothesis. The De la Vaissière proceeded to look for historical data that could allow him to check that hypothesis?

There are census numbers for the region before the dramatic changes brought to local agriculture by the Soviet system in the XX century. According to the census of the Russian empire of 1897, the combined

uezd of Samarkand and Kattakurgan, that is, without the part of the valley downstream from Samarkand, was populated with about 450,000 inhabitants, including poorly populated regions, as the mountains surrounding the valley and the mountainous upper part of the Zarafšān valley. This

uezd did include only 70% of the agricultural lands in the valley, as its western part which contained 30% of the irrigated land within the canals was included in the Emirate of Bukhara which was not covered by the census. So, according to De la Vaissière, if we make use of this ratio to calculate the whole population of the middle and upper valley, this would give an approximate 640,000 population for this area. De la Vaissière then proceeded to slightly reduce this number to exclude the Upper Zarafšān and the mountains, arriving to an estimate of 580-600,000 inhabitants for the middle Zarafšān valley from Waraghsar to the limit of the oasis of Bukhara.

However, De la Vaissière pointed out that archaeological surveys have shown that the valley at the end of the XIX century was far less populated than during its heydays of the VII-X centuries CE. Some parts were no longer irrigated, as the Yangi Ariq zone, and even in the irrigated part many settlements were not reoccupied after the X century maximum. The absolute maximum number of settlements was reached during the period of the VII-X centuries CE. So, De la Vaissière thought that there’s nothing implausible in the 700,000 to 800,000 range for times of economic prosperity and internal peace like it would be the case for the whole of Sogdiana from the middle V century CE onwards (with a zenith during the Samanid era), with only a temporary downward bump caused by the destructions brought about by the Arab conquest of Transoxiana during the first half of the VIII century CE.

There’s also much later data: after the extremely destructive Mongol conquest, in Samarkand and its oasis, but without the valley downstream, there were supposedly 100,000 households. The population in the VIII century at the start of the Umayyad conquest is unknown, but De la Vaissière thought that it might have been only slightly below these numbers. The Arab invasion was extremely destructive in Sogdiana and De la Vaissière thinks it’s reasonable to suppose that the population declined between the beginning of the VIII century CE, before the Arab invasion, and its end, after the numerous destructions of castles, villages and towns which took place, especially under the rule of Abu Muslim. There’s some data from written sources about this period. When the Umayyad general Qutayba ibn Muslim besieged Samarkand in 712 CE, there were 130,000 Sogdians behind its walls. Some of them might have been refugees from the neighboring countryside, and so De la Vaissière estimated that Samarkand might have had in normal time up to 80,000 - 100,000 inhabitants. By comparison, Samarkand in 1897 had 55,00 inhabitants.

According to De la Vaissière, as a grand total for the whole Zarafšān valley, at its agricultural climax under the Samanids, a minimum population of 1.5 million, and maybe more than 2 million would be a likely hypothesis if the numerous depictions of geographers from the X century CE are to be believed.

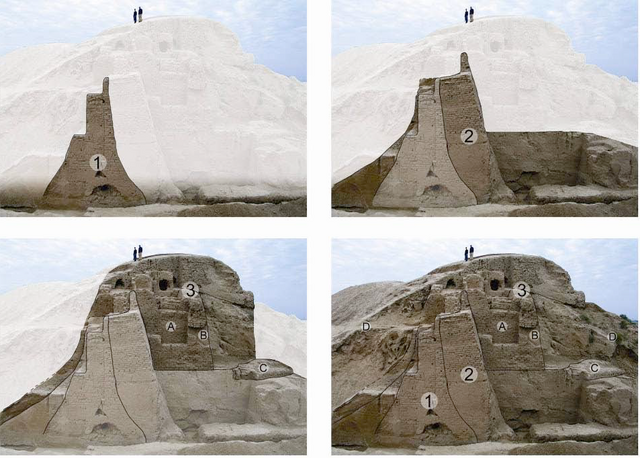

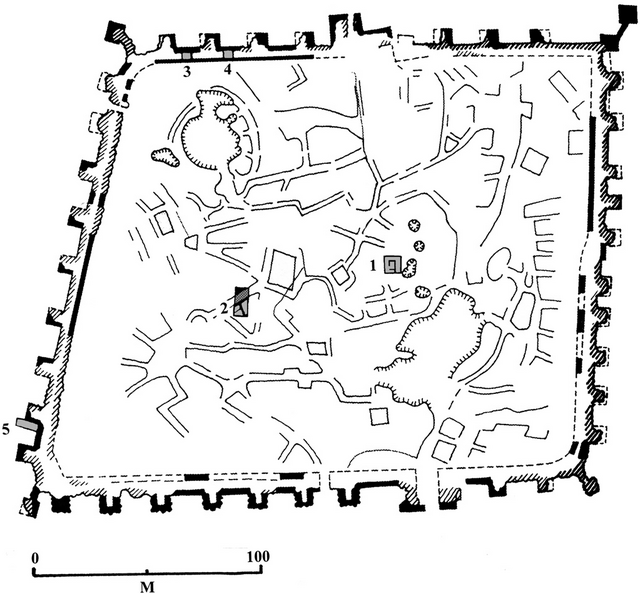

The modern city of Samarkand, which was refunded by Timur, does not stand over the ruins of its ancient and medieval (pre-Mongol) predecessor. Ancient Samarkand stood in the site known as Afrāsīāb, which is now in the northern part of the modern city. Afrāsīāb covers an area of 219 ha, and the thickness of the archeological strata reaches 8-12 m. The ruined site has the shape of an irregular triangle, bounded on the east by the irrigation canal of Āb-e Mašhad, and on the west by the deep Aṭčapar ravine, which in ancient times played the part of a moat. Inside these limits Afrāsīāb appears as a hillocky waste with several depressions sunk over what had once been town squares and reservoirs. In the northern part rise the ruins of the old citadel (a square of 90 by 90 m) with a ramp along its eastern facade. The ruined site is surrounded by earth banks, remnants of fortress walls belonging to four successive ages.

Plan of Afrāsīāb (Old Samarkand).

The settling of the territory of Afrāsīāb began in the VII-VI centuries BCE. Back then, it was already a city occupying almost the entire area of the present site and surrounded by a powerful fortress wall of rectangular, unbaked bricks on an adobe platform. The supply of water was ensured by a canal and open reservoirs (discovered in the eastern and northern parts of Afrāsīāb). The city at the end of this period is identified with

Marakanda, the city conquered by Alexander the Great during his campaign in Sogdiana in 329-327 BCE according to Arrian and Quintus Curtius.

Remains of the walls of the citadel of Afrāsīāb.

The archeological

strata that follow chronologically after the Macedonian conquest identified in the site belong to the period from the IV to the I centuries BCE. Specific for these archeological strata are high quality wheel-turned ceramics that show the influence of the Hellenistic tradition. One of the goblets found bears the Greek name

Nikis, while among the terracotta objects found there are heads that follow the model of the helmeted Athena and Arethusa. Coins of the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter and of the Greco-Bactrian kings Eutidemus and Eucratides have also been found.

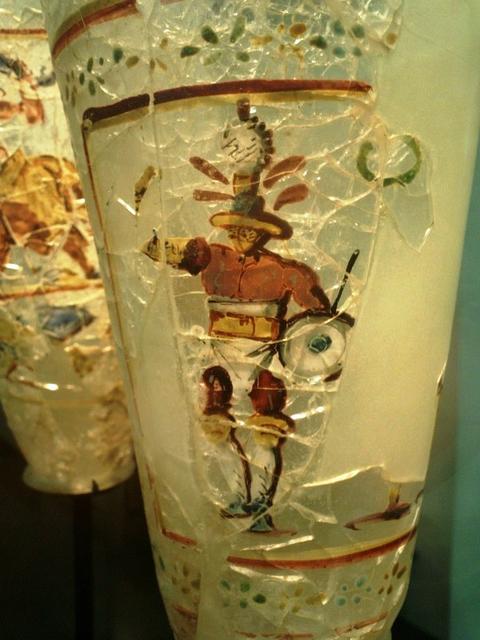

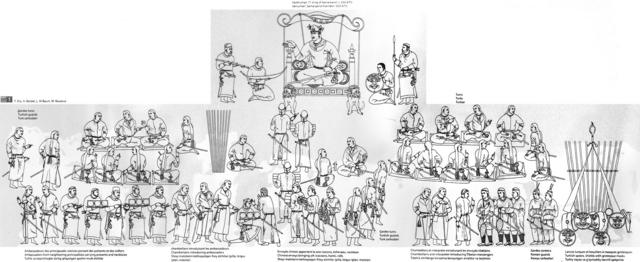

In 1965, Soviet archaeologists uncovered in the site of Afrāsīāb a spectacular finding. They were the very well conserved wall murals that decorated once the reception hall of the particular residence of a rich citizen (it was not the ruler's palace). Due to the scenes depicted in the murals, the hall was nicknamed "the ambassadors' hall". The paintings depict scenes from India, China, Iran and the Turkish lands, and in the best perserved part of the murals, they show foreign ambassadors being brought to the presence of the ruler of Samarkand, from places as distant as China and Korea, with very accurate clothing, weapons and hair styles. They are dated to tsecond half of the VII century CE, when the Sogdian cities were living the heyday of their commercial supremacy over the central Asian trade networks. In the above picture, you can see a hypothetical reconstruction of the ambassadors' hall.

Drawing showing the reconstruction of the main scene of the ambassadors' hall.

The next archaeological layer corresponds to the I – IV centuries CE. Although the extended view among scholars is that the city underwent a period of decline at this time, some other scholars see it otherwise, a view confirmed by excavations of recent years. These have uncovered monumental residential and religious buildings and workshops, in particular the quarter of ceramicists and metalworkers. During that period the aqueduct known as

Jūy-e Arzīz was built, bringing water from the Darḡom canal to the city and new defensive walls were also built. This period would end abruptly in the IV century CE and the archaeological digs show signs of an abrupt shrinking of the city area, which is linked by almost all scholars to the irruption of northern nomads into Sogdiana.

Within the territory of ancient Sogdiana, Bukhara occupies a relatively secluded spot on the western fringes of the Zarafšān hydrographic basin. This is probably why, over the centuries, the Bukhara oasis seems to have been culturally closer to Khwarāzm or Merv (and hence Iran) or, even, Čāč than to the historical heart of Sogdiana, which lies in the area of Samarkand. The Italian scholar Ciro Lo Muzio even wonders if Bukhara, along with the irrigated lands surrounding it, should even be considered an integral part of Sogdiana, and if this could extend for much longer than the two or three centuries of Late Antiquity (V - VIII centuries CE) during which a homogeneous Sogdian cultural pattern is clearly detectable along the whole course of the Zarafšān River. Lo Muzio pointed out that in Soviet archaeological literature about Transoxiana a cautious distinction was made between “Samarkand Sogdiana” and “Bukharan Sogdiana”, to which Lo Muzio would add a third region: Southern Sogdiana, corresponding to the valley of the Kaškā Daryā.

Map of the Bukhara oasis and the Qaraqom oasis to the south, which is formed by a secondary alluvial fan of the Zarafšān River.

Coming downriver from the east (that is, from Samarkand), one enters the Bukhara oasis approximately at Hazara, on the western end of a narrow strip of cultivated land that crosses the Malik steppe along the Zarafšān River. From there, the river turns to the south-west and branches out into a delta which disappears in the sands of the Kyzyl-Kum Desert before reaching the Āmu Daryā (approximately 25 km from its northern bank). The geographical landscape of the Bukhara oasis has been continuously affected by this river and its tributaries, a hydrographic basin which, across the centuries, has been subjected to expansion and shrinking, depending on both climatic and man-made factors among which stands in particular, the artificial irrigation network. Some of its most interesting archaeological areas are now situated on the very edge of the oasis or beyond its modern limits.

During the Bronze Age, an archaeological complex named as the Zaman Baba culture by archaeologists existed in the Bukhara oasis. This period is followed by a rather hazy one, from which the archaeological record only starts to recover during the Achaemenid era, which shows that the lower city (

šahrestān) of Bukhara was already occupied. The following period (IV century BCE – II/III centuries CE) is somewhat better documented in the archaeological record. There are some traces that could hint at a period of Greek dominion over the oasis (under the Seleucids and the Graeco-Bactrian kings), especially the finding in the 1980s of a hoard of Graeco-Bactrian coins at the site of Talmach Tepe near Varaḵša, although not all scholars agree on this; Evgeniy V. Zejmal and Ciro Lo Muzio among others think that there no reliable proof of Greek political control over this area.

But what seems clear is that Hellenistic culture (probably emanating from the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom) influenced the oasis of Bukhara, and particularly its coinage; as local rulers began precisely during this time to issue local imitations of Graeco-Bactrian coins of king Eutidemus (known as “barbarian imitations” among numismatists). Such “barbarian imitations” have so far been found at many sites within the Bukhara oasis (Varaḵša, Ramitan, Kyzyl Kyr, Paykend, and others). Questions about the identity of the rulers who issued these coins, their origins, and the kind of polities they ruled upon are still open. The picture is further complicated by the existence in the Bukhara oasis of another numismatic “stock,” which was struck under the name of “Hyrkodes”, which represent only a very small amount of the total stock found to this time. The obverse of these coins shows a male bust in profile to the right, with receding forehead (probably artificially deformed, a very extended costume among steppe peoples), shoulder-length hair, a band fastened around his head, and a long moustache and beard, accompanied by the inscription “Hyrkodes” in Greek and later on in Sogdian script (as in other Bukharan coins, where Greek was gradually replaced by Sogdian). Scholars are unsure about what did “Hyrcodes” mean. Was it a personal name, a title, or the name of a dynasty? Whatever it must’ve meant, this coinage lasted for a long time; from the I century BCE to the IV century CE; there are also several clues that point to the south-western sector of the oasis as the main minting center for these coins.

"Hyrcodes" coin, dated to the III-IV centuries CE.

According to Lo Muzio, it’s likely that between the II century BCE and IV century CE, two political entities coexisted in the Bukhara oasis; for both of them, however, little more is known than the appearance of their coins. But Lo Muzio considers it possible that both (or at least the “Hyrkodes” dynasty) sprang from the nomad tribal confederations which, from the II century BCE onwards, achieved through conquest a hegemonic position in different parts of western Central Asia. According to Lo Muzio, there seem to be similarities with what has been reconstructed in Bactria after the Yuezhi conquest. “Hyrkodes” coins show some similarities with those of the first Kushan or proto-Kushan rulers, especially

Heraos, at least as far as the ruler’s portrait is concerned. In other words, the Bukharan coinage, in particular the “Hyrkodes” emissions, possibly stems from an ethnic, cultural, and ideological realm akin to the milieu from which the Kushan dynasty emerged.

Lo Muzio thought it very unlikely that the Kushans ever extended their kingdom to Sogdiana; and that surely they never ruled in the Bukhara oasis. He also thought more probable that whoever ruled the Bukhara oasis between the II century BCE and the IV century CE would have had links with the Kangju. This is supported by archaeological findings around the Bukhara oasis, where several kurgans have been found which after being excavated have yielded strong similarities with the ones found in the core area of the Kangju in the middle Syr Daryā both in material culture and funerary practices.

In the Bukhara oasis, the influence of the Kaunchi culture is clearly detectable as late as the III-IV centuries CE in agricultural settlements; material elements belonging to this tradition have been found at the excavations at Kyzyl Kyr, Setalak, Ramitan, Bash Tepe (in the north-western part of the oasis) and in Bukhara itself, in layers dated to the III-IV centuries CE; which up to some point has been linked by scholars to the migration south of refugees from the Syr Daryā valley after the start of the Hunnic invasions.

The oasis of Bukhara was also studied by Étienne de la Vaissière in his study of the early medieval demography of Central Asia. The wall of the Bukhara oasis is partly preserved and delimitates an area of about 3,200 km2. All the early medieval Muslim geographers give a 12x12

farsakhs area to the oasis within its wall: it fits very neatly into the preserved parts of the wall.

A small part of the oasis was outside the wall, controlled by the independent principality of Paykend, on the road to the Āmu Daryā crossing, adding a few hundred km2. Sometimes, this part of the oasis is considered as a separate oasis (the Qaraqul oasis), as in fact it’s formed by a second alluvial fan of the Zarafšān River. The Soviet changes in the irrigation network make nearly useless the currently irrigation network to evaluate the ancient feeding capacity of the oasis, although the descriptions of the ancient canal network in Arabic texts allow a rough reconstruction.

Map of the irrigated croplands in the Bukhara and Qaraqom oasis, according to Étienne de la Vaissière.

De la Vaissière stated that if we were to apply the density calculated for the Balḵ oasis (see my earlier post), that is, the distribution of cultivated land between orchards, annually irrigated and fallow lands as we see it in the Balḵ oasis, a pure hypothesis, then the Bukhara oasis might have fed at least 360,000 inhabitants.

But De la Vaissière thought that the actual population of the Bukhara oasis would have been much higher during its late antique and early medieval heyday, especially in the IX and X centuries CE under Samanid rule. According to De la Vaissière, opposed to the case of Balḵ, the amount of available water was not a problem for Bukhara: actually, there was more water than needed and it overflew to a small lake beyond Paykend, on the Qaraqul secondary fan. This means that there could have been much less fallow land in Bukhara than in Balḵ, and much more annually irrigated land. If all the cultivated land in the oasis was irrigated annually, then the Bukhara oasis could have fed about 800,000 inhabitants, a maximum that does not consider the fact that the area occupied by orchards is quite small in the model applied to the case of Balḵ. Conversely, the excess of water could have created swamps within the oasis.

In favor of this very high hypothesis, De la Vaissière quoted the texts of the Islamic geographers of the X century CE. They described Bukhara as an oasis without any barren track or fallow land, as well as stating that there were thousands of highly productive orchards within it. They added too that the population was so numerous that its agriculture could not entirely feed it. To De la Vaissière, it seems clear that when Bukhara was the capital of the Samanid empire, the upper end of the 360,000 - 800,000 range is the most likely hypothesis. It should have been less so in the VIII century CE but the political geography of the oasis, with the important role devoted to Paykend and Vardāna (see below), both on its outer limits, and of Varaḵša, the residence of the Bukhar Khudah (again, see below), also on the fringe of the oasis, point towards a densely populated oasis.

View of the walls of the citadel (Arg) of Bukhara today. The current walls date to the modern era, but they are built directly over the walls of the old Sogdian citadel, using the same building materials (mudbricks) and techniques.

Unlike Samarkand, the city of Bukhara has grown up during the centuries, without significant interruptions, on its original foundation. The present “old town” center sits on top of the deep archaeological stratification of the ancient and medieval settlement and the citadel hill (

Arg) remained for centuries the seat of the ruling élite until the Soviets overthrew the last Bukharan emir in 1920. This has left very little physical space available for archaeological digs; the remarkable depth of cultural layers (up to 20 m in the

Arg and 16-18 m in the

šahrestān), which in several urban areas are crossed by water tables, are further obstacles that cannot be easily overcome. For these reasons, archaeological research has so far concentrated on very limited areas.

According to the reconstructions by archaeologists, which agree with the written sources, Bukhara was founded in a marshland crossed by one of branches of the Zarafšān River. The first settlement, which has been dated to between the late IV and the II centuries BCE, was situated where the citadel is now located, that is, on the highest of the three hills emerging from the marsh. Later on, the core of the future

šahrestān grew on the other two hills. The only architectural evidence for this foundation period is the remains of a fortification wall in

paḵsa (blocks made of clay mixed with chopped straw) which presumably encircled an area of approximately 2 ha. Until the IV century CE, archaeological information to trace urban history is insufficient, but an evident major break has been detected in the citadel between the I century BCE and the I century CE: a layer of wind-borne sand covers the defense wall, probably marking a period of desertion of the site or a rather long period of time during which the settlement was not fortified. On this layer a new fortification wall was built between the end of the IV and the V century CE.

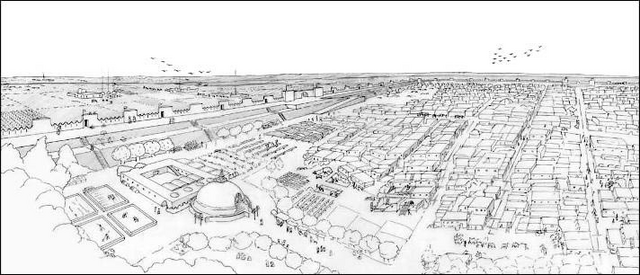

From this time on, the lower town underwent a remarkable transformation and enlargement, gradually taking on the form of the early medieval town. By the VII-VIII centuries CE the

šahrestān occupied a rectangular area of nearly 21 ha, 120 m east of the citadel; on the west side, there were four gates set at regular intervals; on each of the other three sides there was only one central gate. As in other Sogdian towns (Paykend and Penjikent, for example), the

šahrestān of Bukhara was the result of the progressive enlargement of the settlement, which here took place in two main stages: the earliest sector (V century CE) corresponds to the northern half (8-11 ha) bordered on its southern edge by the river; during the VI century CE also the sector (7-8 ha) extending south of the first

šahrestān was also encircled by a fortification wall (on the east, south, and west sides). The entire lower town probably had a regular layout consisting of a grid of rectangular blocks of buildings (somewhat smaller in the southern

šahrestān). An echo of this can be found in the

History of Bukhara written in Arabic by the local historian

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Jaʻfar Narshakhī in the X century CE, who wrote that the walls of the Bukharan

šahrestān were built by order of the Turkic prince

Šer-e Kišwar (identified as

Tardu, son of the Türk khagan

Istämi) who ruled Bukhara in the second half of the VI century CE.

Bukhara was not the only major site in the oasis though. Varaḵša was one the major archaeological discoveries made in the Bukhara oasis, and the first to reveal the existence of a Sogdian school of painting. The site is situated on the northwestern edge of the oasis, on the verge of the Kyzyl-Kum Desert and on the route to Khwarāzm. It was identified by scholars with Narshakhī’s

Farakhsha already before 1917, and excavations were conducted in the site in 1937 and then again between 1948 and 1954, conducted by the Soviet archaeologist V. I. Shishkin. According to Narshakhī, Varaḵša was “the largest of the villages […] as large as Bukhara but older,” a statement that seems to suggest that, even in its heyday, this fortified settlement did not hold the rank of town.

View of the remanis of the Bukhar Khudahs' palace in Varaḵša.

Varaḵša was founded possibly in the early first millennium CE, if not before, as Shishkin believed. The excavations, however, shed light mainly on the latest phases of its existence; in particular, Shishkin’s efforts concentrated on the remains of the

Bukhar Khudah palace in the citadel.

Bukhar Khudah was the title adopted by the local rulers of Bukhara from the VI century CE onwards, and it was in Varaḵša that they built a large palace where Soviet archaeologists found a series of impressive wall paintings that revealed for the first time that during the VI and VII centuries CE a significant Sogdian school of painting appeared and developed out of Bactrian and Indian influences, and which reveals close links with the famous paintings found at Buddhist sites in the Tarim Basin. Rather than in the late V or early VI century CE, as Shishkin thought, the palace was founded in the VII century CE, most probably in its last decades, by will of

Khunak Khudah, a sovereign attested also in the coinage. The palace was further expanded and reformed by his son and successor Toghshada (709 – 739 CE), and the latter’s successors Qutayba and Bunyat. The land surrounding Varaḵša, within a radius of about 10 km, is one of the richest sections in archaeological sites in the whole Bukhara oasis, and during the 2000s it was excavated by the Uzbek-Italian Archaeological Mission.

Another great set of Sogdian wall paintings was discovered in the remains of the palace of Varaḵša during the excavations led by the Soviet archaeologist V.I. Shishkin in the 1950s and early 1960s. They decorate the walls of another reception hall, and due to the red background of the scenes, the hall was called "the red hall". These paintings depict the Sogdian deity Adhbag (the Sogdian name of Ahura Mazdā) fighting against the beast of evil. Above you can see a hypothetical reconstruction of the red hall.

Detail of one of the murals in the red hall.

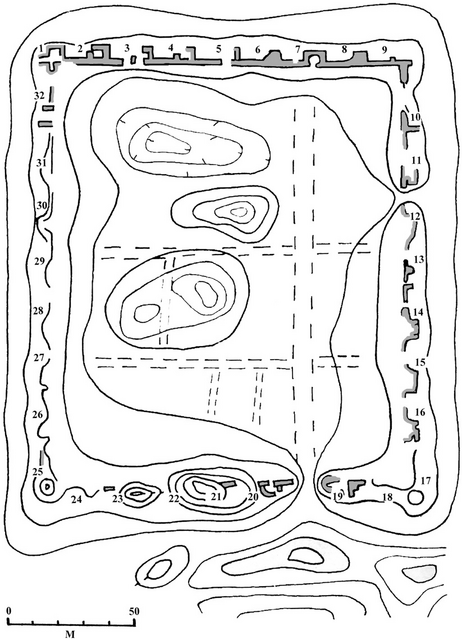

Paykend was the westernmost Sogdian town, located 60 km southwest of Bukhara, at the very southernmost tip of the Bukhara oasis. For archaeologists, it is one of the few Sogdian urban sites that shows an almost unbroken continuity between the late antique and early Islamic periods. Systematic excavations started only in 1981 and are still under course. The first fortified settlement (1 ha) was founded in the III - II century BCE on the hill which later hosted the late antique citadel, but Paykend was not raised to the status of urban center before the late V or early VI century CE. In this period the layout of the lower town took shape. As in Bukhara, it consisted of two adjacent

šahrestāns (an eastern one covering 7 ha and a western one that covered 13 ha), separated by a short chronological gap. The street layout, which remained unchanged even after the Arab conquest, subdivided the urban area into blocks of various shapes and sizes. In the citadel, excavations have brought to light a temple (considered by some to be a fire temple, but that’s disputed) and a palace. Excavations in the southeastern corner of the citadel revealed also a “treasury” building (connected with a religious building) which included a number of remarkable items that seem to have been gathered over a long span of time: coins, bullae, and elements of armor and weaponry.

Remains of the walls of Paykend.

According to Narshakhī, another major center was

Vardāna, the seat of the

Vardan Khudah. The ruins of this town (which, according to Narshakhī, was older than Bukhara and defended by a strong city wall) have been identified with the site of Vardanzeh. Extending over a nearly rectangular area of 11 ha, Vardanzeh clearly shows the outline of a rectangular fortified citadel (at the northeastern end) and a lower town; the latter (as at Bukhara and Paykend) probably consisted of a double

šahrestān; the first adjacent to the southwestern side of the citadel and of a regular rectangular shape, the second farther to the southwest, probably resulting from the progressive and unplanned agglutination of different built-up areas. Since 2000, it’s been under excavation by the Uzbek-Italian Archaeological Mission.

Both Narshakhī’s

History of Bukhara and the excavations carried out in the Bukhara oasis have allowed archaeologists and scholars to get a much more detailed image of the outlay of Sogdian society and culture. As in the Iranian Plateau, Sogdian society was ruled by an aristocratic elite that ruled from fortified citadels and castles and who derived their wealth mostly from agriculture.

Khudah in Sogdian meant precisely “lord”, and the references to several such “lords” within the Bukhara oasis by Narshakhī points towards a “feudal” organization of the society; what’s unclear in the case of Bukhara is how to reconcile this with the fact that coinage attests to a unified minting authority from the IV century CE onwards; and the same can be said about the very long wall that surrounded the oasis and the dense network of irrigation canals; these infrastructures could only have been built and maintained if there was a single political authority ruling over the whole oasis.

Excavations in Samarkand and the Bukhara oasis, as well as the works of Narshakhī and several other early Islamic historians have also allowed scholars to get a better understanding of the religious landscape of Sogdiana. The majority of the population followed the traditional Iranian religion, which could also be described as a local version of Zoroastrianism that was not influenced by the religious reforms that had been implemented by the Sasanian dynasty in Iran and by the teachings of the established Zoroastrian religious hierarchy of the Sasanian empire. This religion seems to have been centered mostly around the veneration od deities associated with agriculture and water and the performance of rituals associated with the agrarian calendar. From the V century CE onwards, Sogdiana entered a period of exponential growth and great economic dynamism associated with an increase of the volume of trade that ran through the “Silk Road”, and accordingly the religious scenario in Sogdian cities became much more diverse. The local version of Zoroastrianism continued as the majoritarian religion, but in the growing commercial centers, large communities of Jews, Nestorian Christians and Manicheans appeared. But curiously enough, Buddhism failed to expand into Sogdiana, despite the fact that Sogdian territories were the necessary terrestrial link between the great Buddhist centers in Gandhāra and Bactria on one side and the Tarim Basin and China in the other, where Buddhism was growing and spreading. All the Chinese pilgrims that traveled to India crossed Sogdiana, but all of them agreed (as archaeology corroborates) that the presence of Buddhism was at the very best testimonial in this country.

One of the deities venerated in the Sogdian religion was Nana, a goddess of Mesopotamian origin whose cult reached Central Asia during Achaemenid times. Here you can see her depicted in a silver bowl with obvious Sasanian influences.

As it can be seen from what I’ve written above, Sogdiana shared many cultural traits with Iran, and one of these traits was a common legendary background. The mural paintings from Afrāsīāb, Varaḵša and Panjikant depict scenes that appear also in Ferdowsī’s

Šāh-nāma, which shows that the Iranian Sogdians shared the same myths and heroes with the Iranian populations within

Ērānšahr. One of the characters of Ferdowsi’s epic,

Siyāvaš, was venerated in Sogdiana (and in Khwarāzm) and its inhabitants performed rituals and sacrifices dedicated to him. According to the Soviet historian Sergey P. Tolstov, Siyāvaš would’ve been venerated as the Central Asian god of dying and reviving vegetation. And within Iran proper, the murder of Siyāvaš is commemorated in Širāz in Fārs as the day of

Savušun still to this day.

Panjikant was a Sogdian city whose remains are located in the southern periphery of the present-day city of Panjakent in western Tajikistan. At the beginning of the VIII century CE Panjikant was the main settlement of the

Panč district, a fact reflected in its name. Some scholars hold that Panjikant was could be identical to the city of

Bo-xi-te named in Chinese sources of the Tang dynasty and consider it to be identical with the capital of the principality of

Māymorḡ, mentioned by that name in Chinese histories from the Tang period, and which would have been located to the south or southeast of Samarkand, but this identification is quite dubious.

View of the remains of Panjikant.

Panjikant was the easternmost city of Sogdiana proper. Further to the east, across the valley of the river Kshtut, lay

Pārḡar, which at least in the IX - X centuries CE and perhaps even earlier was part of Osrušana. In the early 8th century it was within the domain of prince

Dēwāštič (708? – 722 CE), ruler of Panjikant. The Panjikant of the V - VIII centuries CE is known primarily from extensive archaeological excavations, while the scarce information about the relatively short period of Dēwāštič’s rule is derived mostly from documents found in the remains of the fortress at Mount Moḡ. In 721 – 722 CE Dēwāštič claimed the title of “king of Sogdia and lord of Samarkand”. The Arabs initially recognized his new title, but soon forced him to flee to Pārḡar, and later to the castle on Mount Moḡ, where he was finally captured; excavations in this site have yielded a large number of documents dated to the Arab siege of the fortress and which are commonly known as the “Sogdian letters”. After holding him prisoner for a few months, the Arabs executed him and Panjikant had no more native rulers.

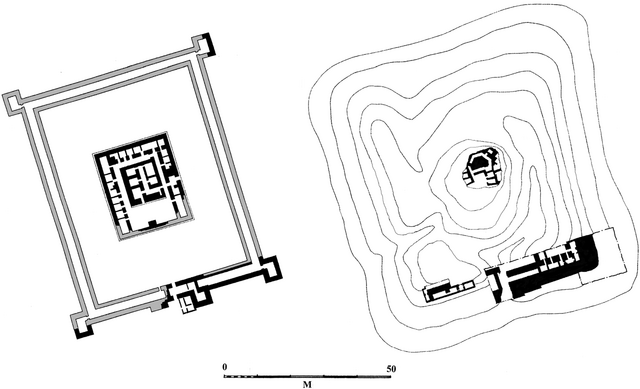

Map of the ancient Sogdian city of Panjikant. It was not a big city, but it has become famous due to the fact that it has been intensively excavated and that it was abandoned some fifty years after the Islamic conquest, which has allowed archaeologists to get a very good impression of an ancient pre-Islamic Sogdian city. This, and the documents of Mount Moḡ give us a very vivid impression of ancient Panjikent in the eve of the Arab conquest.

The site of Panjikant has been extensively excavated since 1937. After more than half a century of systematic archaeological investigations, Panjikant has become one of the most thoroughly studied late antique cities not only in Sogdia, but in Asia as a whole. The excavations show that this city, situated on the rim of a high terrace overlooking a fertile, well-irrigated valley, was founded in the V century CE and was inhabited until the 770s.

Its citadel is separated by a ravine from the

šahrestān or lower city, which lies to the east of the citadel and is surrounded by fortified walls of its own. Two additional walls cross the ravine, linking the

šahrestān with the citadel, and creating a unified defensive system around the entire city. The central structure of the citadel is a fort with a square array built close to the northern part of a mountain ridge, which runs from south to north. In the end of the VII or the early VIII century CE, a square keep was erected in the southeast corner of the fort. At the foot of the fort and to the north of it lies the lower fortification, watered by a natural spring. It shows traces of habitation from the II century BCE to the I century CE. This cultural layer contains remnants of ceramics, but none of buildings. To the south of the fort stood a fortified wall, which defended the citadel against attacks from the top of the ridge. There were no buildings between the wall and the fort. On a hilly site to the east of the fort rose once the richly decorated palace of Dēwāštič, which apparently burned down in 722 CE, probably during the Arab conquest of the city. It was an expansion and an extensive reconstruction of an earlier building, dating from the VI century CE. Another palace from the VI century CE was located in the lower fortifications.

Large numbers of wall paintings have been discovered in the remains of Panjikant, depicting a wide array of courtly, religious or mythic scenes. Here you can see a courtely scene; the figure on the left is a Sogdian ruler.

In the V century CE, the area of the

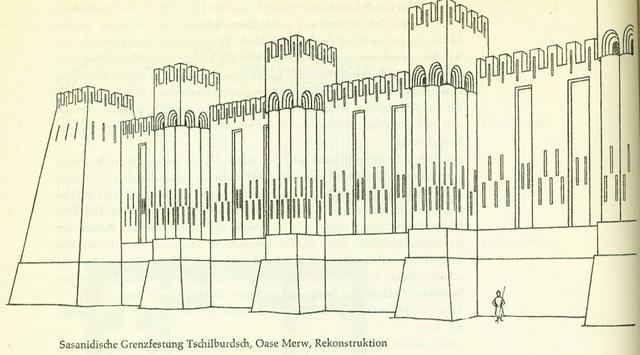

šahrestān (without the citadel) measured about 8 ha. Straight fortified walls defended the settlement: the northern wall running along the rim of the terrace, and the eastern wall perpendicular to it. The southern wall ran straight only where the terrain permitted, and the western wall followed the irregular edge of the hill, departing from the overall regular design. The city walls of Panjikant in the V century CE were ten to eleven meters high, bristling with numerous towers, and punctured by embrasures in a chessboard pattern. Later, the walls were made thicker, with fewer towers, a sloping façade, and no embrasures close to the foundations. The residential buildings of the city consisted of several small rooms with low wooden ceilings. All walls were made of sun-dried brick and clay. The streets and alleys intersected at right angles. The spot at the city center, where two temples stood, had apparently been reserved for religious purposes since the founding of the settlement.

Reconstruction of the two temples in the center of the lower city of Panjikant.

The architectural style of the temples, which by the beginning of the VIII century CE had undergone many reconstructions, can be traced back to the traditions of Hellenistic Bactria. The two temples are very much alike: each consisted of a central building facing east and surrounded by a yard, which was adjacent to yet another yard to the east, with an exit to the street. A visitor walking from the street towards the main building would have seen the sacred spaces of the two yards open before his eyes one after the other, until, standing in the inner yard, he would have seen not only the portico, but also the interior of the central hall, which opened directly onto the portico of the main building. At the far end of the hall there was a door leading to the

cella, and on each side of it two niches with clay statues of divinities. A characteristic feature of these Sogdian temples was their openness to the rays of the rising sun and to the eyes of the laity. The passageways to the corridor, which circumvented the hall and the

cella behind it opened onto the portico to the sides of the central hall. Both temples were dedicated to the cult of the gods. A space for the sacred fire was added to “Temple 1” only in the late V or early VI century CE.

The earliest burials in the necropolis at the edge of the ancient city, with Zoroastrian ossuary burials characteristic of Sogdia and Khwarāzm, are dated to the V and early VI centuries CE. By the end of the V century CE the area of the city had grown to 13.5 ha and new fortifications were built to the south and east, so that part of the old walls was enclosed within the perimeter of the new ones, dividing the city into inner and outer quarters. The walls of the inner city were repaired and reinforced in the VI and VII centuries CE.

The paintings from one of the private residences in Panjikant described scenes of the epic cycle of the Iranian legendary hero Rostam, the great hero of Ferdowsī’s Šāh-nāma.

The two temples contained statues and murals from their foundation. The earliest murals in the palaces of the citadel date from the VI century CE. Some of the houses built during the VI century CE were two stories high, with vaulted ceilings on the lower floor, and murals on the walls of some rooms. However, during the V - VI centuries CE, no building in Panjikant could rival the magnificence of the two temples, and even the houses of the richest residents appeared rather humble in comparison. In the VII - VIII centuries CE, though, it was the houses of the rich that set the tone of urban architecture in the city. The end of the VII century CE and especially the first quarter of the VIII century CE marked the heyday of late antique Panjikant. All residential houses from that period (not only those of the rich, but also of simple well-to-do citizens) were decorated with murals and woodcarvings, and these murals have provided archaeologists with a large amount of information about ancient Sogdiana. These murals contain scenes from the Iranian epic of

Rostam (the great hero of the

Šāh-nāma), but also from Aesop’s fables, from the

Mahābhārata, the

Pañcatantra and the

Sendebād-nāma (which would later become the stories of Sinbad in

The Thousand and One Nights), in a pictorial display of the cosmopolitan tastes of the cities of late antique Sogdiana.

Keš was another important ancient Sogdian city, located in the upper Kaškā Daryā valley, and corresponds today with the modern town of Shahrisabz in Uzbekistan. To its north, a road leads to Samarkand; the oasis of

Naḵšab is located downstream to the west; and to the south there is the Iron Gates Pass that leads to Termeḏ in Bactria. Archeological excavations some 12 km north of Shahrisabz have uncovered the large (70 ha) settlement of

Padaytak Tepe that includes the fortress of

Uzunqïr. This settlement has been from the VIII century BCE to the Achaemenid period. The town is first mentioned in Aramaic administrative documents from Ḵolm, dated to late Achaemenid times and which deal about the renovation of its walls. In the histories of Alexander the Great’s conquest of Sogdiana, the name

Nautaca probably refers to the same region, and the fortress of

Sisimithres where Bessos was captured in 329 BCE has been identified with Uzunqïr by the French historian Frantz Grenet. The citadel of the Hellenistic settlement at Keš lies at

Kalandatepa, located within present-day

Kitab, 5 km to the north of Shahrisabz, and the remains the late antique city (covering a surface of 40 ha) lie nearby.

View of the site of Shahrisabz.

Keš figures prominently in dynastic Chinese histories (where it’s named

Shi). Its ruler

Dizhe, who would’ve ruled between 605 and 615 CE, even announced his vassalage to the Chinese emperor, and his successors sent regular embassies to the courts of the Sui and Tang emperors.

Early Islamic authors located the principality of

Osrušana (also spelled

Ustrushana in English) north of Sogdiana proper, between it and the entry to the Ferghana Valley. It was traversed by the main caravan road that linked Samarkand with the Ferghana Valley and further eastwards with the Tarim Basin and China. According to the X century CE Muslim authors Ibn Ḵordāḏbeh and Ibn Ḥawqal, Osrušana was a region comprising plains, (whose fertility, agricultural richness, and pasturelands were praised by said geographers), and hills and, in the south, the Turkestan and Zarafšān mountains which were usually reckoned as belonging to it administratively. These mountains were rich in minerals; and gold, silver, salt, ammoniac, and vitriol were obtained from them and exported; above all, the local iron ore was used to produce tools and weapons that were exported as far away as Khorasan and Iraq.

These authors described the region as little urbanized, and it long preserved its ancient Iranian feudal and patriarchal society. The main settlement, described by early geographers as the ruler’s residence, was

Bunjikaṯ (according to the

Ḥodud al-ʿālam). It was identified in 1894 with the locality of Šahrestān, some 25 km from the modern Uzbek town of Ura-Tyube at the entrance to the Ferghana valley. At the time of the Arab conquest, Osrušana was ruled by a local dynasty of Iranian princes, the

Afšins, who managed to retain their title and lands for two centuries (until 893 CE) after the Arab conquest after converting to Islam. The most famous of them was the general of the Abbasid caliph

al-Moʿtaṣim (833 – 842 CE), the

Afšin Ḵayḏar or

Ḥaydar ibn Kāvus. Osrušana was one of the Sogdian principalities that put up a strongest resistance to the Arab invaders, and the

Tangshu also records its sending of several embassies to the Tang court asking for military help.

Fragment of a wall painting found in the remains of Bunjikaṯ. It is dated to the early Islamic era, and it shows the persistence of Sogdian-Iranian traditional religion and artistic tradition after the Arab conquest.

Another important city located at the entry of the Ferghana Valley was Khujand, which is today a city in northwestern Tajikistan located on the middle course of the Syr Daryā River, about 150 km south of Tashkent. The origins of Khujand are obscure, but archeological evidence indicates the existence of an urban center there as early as in the VI to V centuries BCE. Alexander the Great appears to have built a city, called

Alexandria Eschate (Alexandria the Furthest), near or encompassing the site of the present city during his campaigns in the region in 329-327 BCE, and some scholars identify it with Khujand. The city first appears under its current name in early Arabic and New Persian sources as

Ḵojanda. According to Tabarī, the city fell to the Arabs in 713 CE, but it rebelled and was besieged for a second time by the Umayyad army in 722 CE; after storming it the Arabs burned the city and massacred its inhabitants.

As for the Ferghana Valley itself, it was never a part of the Achaemenid empire and there’s no convincing proof that Alexander the Great ever conquered it. Archaeology has found no evidence for urban centers in the valley for the Achaemenid and Hellenistic eras, and Ferghana only enters the accounts of written history until it was invaded by the army of the Han emperor Wudi in 104 – 101 CE. Despite the lack of written accounts, the material culture shows similarities to that of other contemporary Eastern Iranian peoples of Central Asia, and so historians believe that the original population of the valley was of Iranian stock (still today, part of the valley’s population is Tajik).

Landscape view in the Ferghana Valley.

Unlike Sogdiana, ancient Ferghana had no coinage of its own. Finds of Chinese coins, mirrors, and textiles are more frequent in Ferghana than in the neighboring lands. This testifies to its well-established links with China. After the beginning of the Common Era though the influence of other Central Asian cultures on Ferghana became markedly stronger, especially in burials. The variety of burial customs probably reflects the co-existence of several different ethnic groups of nomads and semi–nomads, the tribes of the so-called Kaunchi culture. These originated most probably from Čāč and later gradually penetrated into the Ferghana Valley. In general, however, the culture of Ferghana still preserved at that time many of its original features. Several local variants of this culture have been identified by archaeologists. Fortified rural estates, “castles” with bastions and arrow slits, are characteristic of this period (similarly to Sogdiana). Often they are surrounded with a settlement, and the architecture of the fortified buildings finds very close parallels in Sogdiana and the Iranian Plateau, although at the same time local pottery is noticeably different from Sogdian pottery. Like other Central Asian settled lands, the IV-Vi centuries CE show a marked decrease in the number of settlements, but unlike in Sogdiana, it seems that recovery in the Ferghana Valley took a longer time. This period also witnessed the first appearance of burials according to the Turkic custom after the valley was annexed by the Türk Khaganate in the VI century CE. Some of the VIII century CE rulers of Ferghana were of Turkic origin (same as it happened further south in Sogdiana proper).

According to the Chinese pilgrims that crossed the valley, the population of Ferghana spoke its own dialect in the late antique period, different from Sogdian. But at the same time archaeological sites of the VII - VIII centuries CE reflect the spread of Sogdian culture and language; local coins, in particular, display Sogdian legends. Sogdian customs, such as ossuary burials, were also adopted in Ferghana. In the suburbs of the ancient city of

Kuva, several houses and a temple dating to the VII to early VIII centuries CE have been discovered. The architecture, pottery, and the clay sculpture are very close to Sogdian patterns. The temple was first thought to be a Buddhist shrine as the iconography of its sculpture revealed distinct Indian features, but similar features, however, are present in the iconography of the native Sogdian gods (as in Panjikant). According to the German scholar Markus Mode, the temple was dedicated most probably to the Sogdian equivalent of Ahura Mazda, represented as the Indian god Indra.