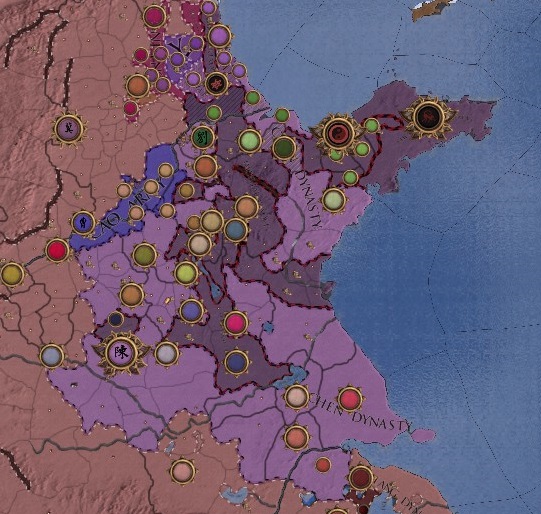

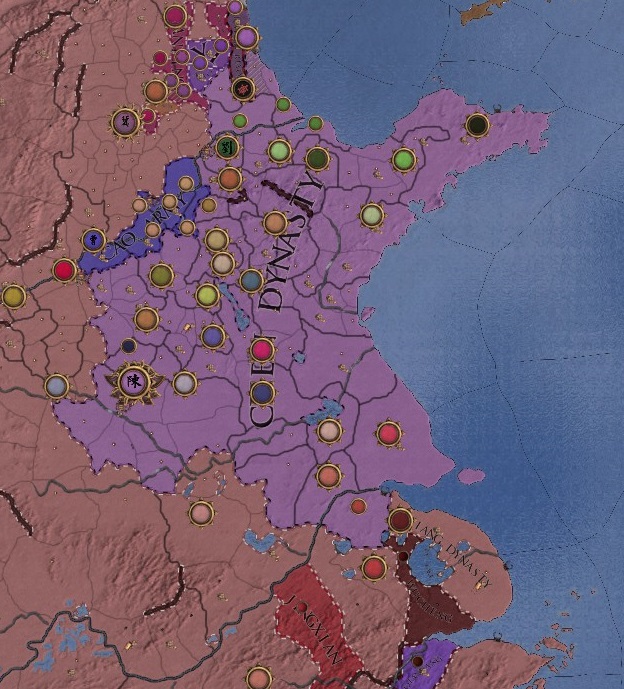

225: PEACETIME IN THE CHEN DYNASTY

Emperor Cheng had won, defeating and executing the rebels that had sided with the traitor Tan Shanquan, who had his whole Clan slaughtered as thoroughly as possible. But while the Emperor could only smile at this efficient cruelty on his part, he didn’t feel like he had truly won. He had been forced to compromise with Yi Shing and his ilk, who now held important positions at court. While in public he showed the face of a calm and reasonable emperor, in private he fumed and stressed out against this strong-arming of his imperial prerogatives. He was the Son of Heaven, the true ruler of China! Yet here he was, being forced to accept traitors and reward them with high-ranking offices withing HIS dynasty. This was humiliating. This was insulting! And clearly, someone had to have done a great mistake for such calamity to befall the dynasty.

And three weeks after peace had returned to the Chen, the Emperor decided to punish one of these “guilty officials”. But to everyone’s surprise, this punishment was not handed to one of the former rebels, but to one of the generals that had just fought and won the civil war for Emperor Cheng. Liu Xian was brought to trial by the Emperor, who saw too much ambition in the general’s eyes. Yet his ambitions were rooted within the Chen Dynasty, and he never had any intentions to act against his lieges. But now the Emperor was blaming his officers for their failure to end the revolts. Liu Xian was brought to Chenguo where, to Emperor Cheng’s credit, he was given a trial instead of being simply punished for his failures. And it was not a complete sham.

The trial was the biggest affair of January and February, taking the attention of anyone who was someone within the Imperial Capital. However, every testimony favored Liu Xian. Chen Tiao, now Marquis of Jiyin, described Liu Xian as an exemplary general and a good official. Tao Boyang, the last Governor of Xu Province before it was conquered by Chen, also came to Chenguo to present his own testimony. He only had good things to say about Liu Xian, who had remained loyal to him until the very last unlike other officers. Even the Crown Prince Xiao Tung came to Liu Xian’s defense. Whatever accusations were brought against the man were dropped as the Emperor recognized that Liu Xian was probably not the guilty party. It didn’t stop Emperor Cheng from quietly firing Liu Xian as magistrate and removing him from his generals. While Liu Xian would eventually be appointed as magistrate of another county in 229 and die at the old age of 80 in 238, this marked the end of his prominence within the Chen Dynasty.

This tyrannical display of authority did not sit well with the court. Many officials who had recently taken part in Yi Shing’s revolt had hoped that the Emperor would have learned his lesson by now, that he would change to prove a more righteous ruler. But the Emperor was not going to bend his own values just because of a small setback. He was the Son of Heaven, the true ruler of China. And no one could avoid his justice and his will. If anything, he had come out of the civil war more convinced of himself and more distrustful of his subordinates, who he saw as either incompetent or unreliable. His son Xiao Hanhe, who served as one of his close advisors, was certainly noticing the discontent among the officials. He also noticed how little his father seemed to care about criticisms these days, which is why he was too scared to point out the current situation to Emperor Cheng.

One person who surprisingly supported the Emperor’s action, even to his own surprise, was his daughter-in-law the Crown Princess. Having been raised by the strong and sometimes violent Budugen the Great, she saw her father-in-law’s actions as a show of power, not abuse of his authority. But she was also playing it smart. Changle wasn’t stupid. She knew that while the bullying stopped, she remained a weakness for her husband and her sons. And considering how the relationship between her husband and father-in-law was slowly disintegrating, she needed to do everything in her power to help protect their succession rights. Not that she had the courage to oppose Emperor Cheng anymore, considering what he did to those that stood against him. This meant that Changle became a surprising supporter of the Emperor, leaving Xiao Tung flabbergasted and confused about her new stance.

The peasantry was clearly not a fan of the Emperor and his policies though, as some of them decided to rise up in February. They were partially made of former veterans who had sided with the rebels and feared for their lives, though they were joined by men and women who disliked the harsh laws of the Chen Dynasty. Whatever their reasons, they revolted and started to agitate against the local government. And they were surprisingly successful in recruiting people to their cause. By the end of the month, they had almost five thousand rebels under their banner, a sizeable number that certainly took the Chen court by surprise.

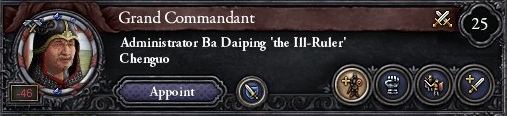

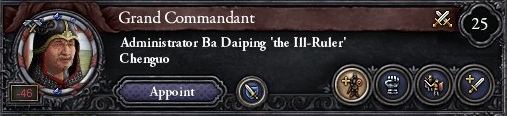

The Emperor immediately dispatched an army to handle the revolt. The new Grand Commandant

Hu Zan came forward and advised that he led the response, as he was obviously the best general currently serving the Chen Dynasty, a fact showed by his current office. He also demanded that the Crown Prince accompany him on this heroic campaign against the rebels. But Emperor Cheng refused these demands. He appointed Hu Zan to bring an end to the civil war, not to allow him to rack up prestige and glory. And Hu Zan also wanted Xiao Tung to help him? He had become quite suspicious of his son and now wished to keep him as closed as possible for safety. His own safety.

Instead of sending Hu Zan, Emperor Cheng decided to give command of this expedition to Ba Daiping, another great general who had defected to Yi Shing during the recent civil war. Ba Daiping had previously been a close ally of Tan Shenquan before Qing Province was annexed, which might make his appointment puzzling. But unlike Hu Zan, Ba Daiping lacked the political skills to thrive at court, being little more than a military man. This alone made him a far more appealing option than the Grand Commandant. To assist him on this campaign was the young Chen Gongwei, a young administrator known for his loyalty to Emperor Cheng, being defeated by Tan Shenquan and his hardworking nature.

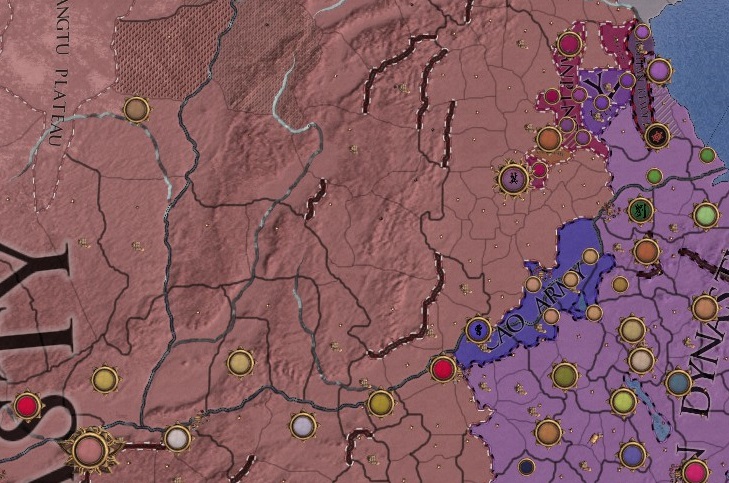

It was around that time that Emperor Cheng was made aware of the Liang campaign against Anping Commandery. This was right on his new northern border, a clear threat to the safety of the dynasty. After consulting with his advisors, the Emperor decided that this could not stand unanswered. He dispatched envoys to Zhao Yun offering him help from the Chen Dynasty. However, the warlord rightfully feared that the Chen might use this as an excuse to gain influence within his territories. Refusing to recognize the Chen, let alone accept its help, Zhao Yun had the messengers escorted outside of his borders as he prepared to face

Emperor Anwu.

But while Zhao Yun was not interested to side with the Chen Dynasty, others were far keener on this offer of imperial protection. The Magistrate of Yi was a middle-aged man named Shih Zhengyi, who had inherited the position when his father passed away in 207. Through a mix of luck, excellent management and not being noticed due to his inherent weakness, Shih Zhengyi had managed to remain independent since inheriting his lands. But now he could clearly see the pressure of the Liang Dynasty coming toward him. And if he was going to submit to a new imperial dynasty, then it would be on his terms. He sent an offer to Chenguo, proposing to submit himself to the Chen Dynasty in exchange of recognition of his office of magistrate and reinforcements to bolster his garrisons. Emperor Cheng didn’t even have to think twice before he agreed, and by the end of March the Chen Dynasty had expanded once more.

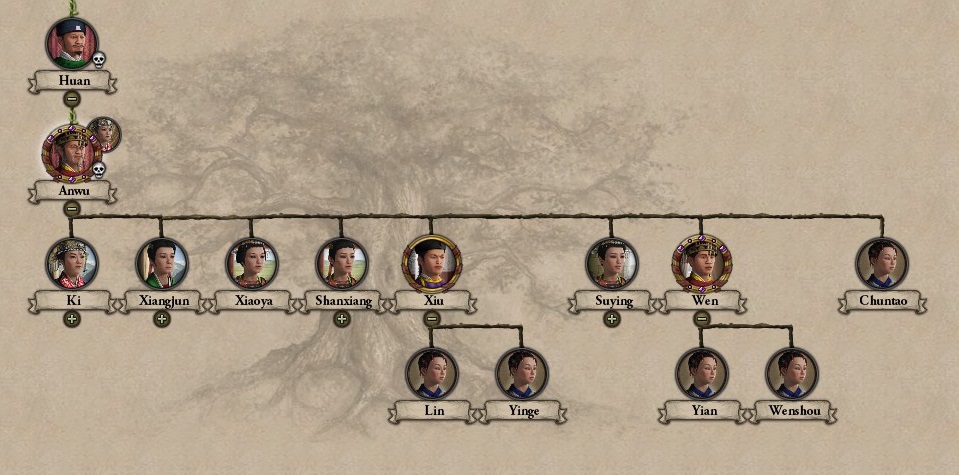

In early June, Emperor Cheng was hit with the loss of his wife, the young Fahui. When he had married her, he had found her surprisingly honest with him, which he found refreshing and likeable. Even so, she was only made his first consort when he founded the Chen Dynasty. Emperor Cheng never promoted her to the rank of empress as he didn’t want to threaten his sons’ position in the succession should Fahui produce him a son. But they never produced any child together, in part because the Emperor’s gout making any sort of physical activity a chore. And then she caught the flu and died from it at the age of 28. She had entered Chenguo as a maid to Changle, only to end up as the wife of the first emperor of Chen. Her loss was palpable, and while he promoted another concubine to the rank of First Consort, his entourage noticed that the absence of Fahui only made his mood fouler.

The peasant uprising was able to go on for months before Ba Daiping was finally able to corner them in mid-July. The general had been forced to fight a long protracted war against the rebels, who held many bases in their home region and remained unwilling to surrender even after a defeat on the field of battle. But in the end, their resilience proved futile against the trained veterans of the Chen military. Ba Daiping (and Chen Gongwei, but he was mostly ignored) returned to Chenguo as a hero. Which gave Emperor Cheng the perfect excuse to fire Hu Zan as Grand Commandant and replace him with Ba Daiping, a move that took both men by surprise. Hu Zan played it nice at court, but he later spoke with Chen Tiao, the Marquis of Jiyin, where he voice his displeasure by saying: “I cannot wait for the Crown Prince to sit on the throne.” Surprisingly, the ever loyal Chen Tiao did not report these comments to Emperor Cheng, as he was in fact starting to agree with them.

While the Liang Dynasty did its best to stop the news from spreading, it eventually reached Chenguo in August. The Chen Imperial Court learned that Emperor Anwu had died in mid-July. The great usurper, the evil pretender, the dynastic rival… All nicknames for the number one enemy of the Dynasty. And now he was gone. This great threat had passed away while Emperor Cheng continued just fine (minus that terrible gout). Truly, Heaven favored the Xiao Clan. The Emperor was quick to organize celebrations, with officials readily bringing their praised of the Emperor and his dynasty, which was clearly the true heir of the Han.

These praises eventually put a plan in the Emperor’s mind. The Liang Dynasty was now ruled by an inexperienced and young Emperor Wen, who was barely older than his own grandson. The Liang military was distracted with their campaign against Anping. Now might be the time to strike at the Liang Dynasty and take back lands that were rightfully Chen’s. After all, the Chen was the heir of the Han, and thus had a legitimate right to the whole of China. And now ambitions of reunifying China were appearing in the Emperor’s head. A weak ruler like Emperor Wen could easily be defeated. And even if his advisors were competent, Emperor Cheng had better ones! His generals were the greatest in China! Yes… Victory would soon be his!

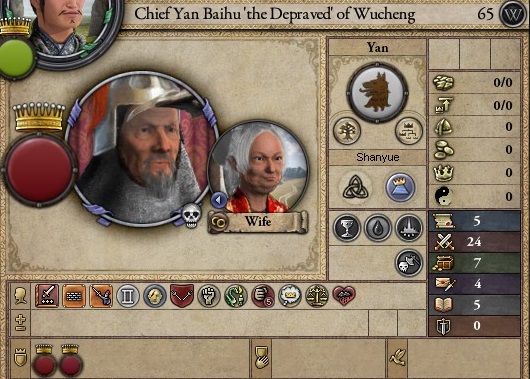

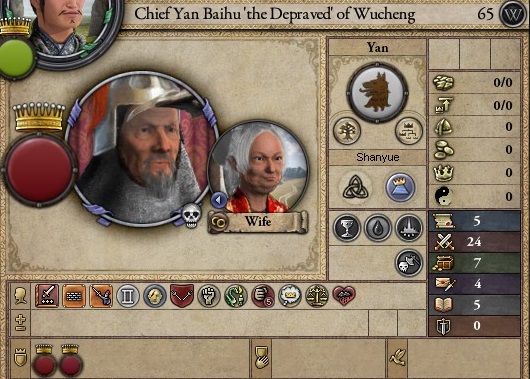

Over the following months, Emperor Cheng and his advisors devised a dubious plan to seize large amounts of territories from the Liang Dynasty before it could settle in with its new emperor. Well, mostly just the Emperor. While he did listen to advises from others, he did not take any criticisms nicely. His new plan hinged on the recent death of two individuals. First was of course that of Emperor Anwu, but he was surprisingly not the most important death in this plan. The Shanyue chieftain Yan Bayu had died in April 225, leaving his lands divided between his two oldest sons. While the obvious choice might have been to attack Yan Bayu of Wucheng, as his lands bordered the Chen Dynasty, Emperor Cheng instead went for the further away Yan Dahu of Fuchun. The Chen Army would force him to submit as a tributary, thus giving the Dynasty an allied base in the Hangzhou Bay. From there, they would seize Yang Province while the Liang army was distracted in the north and then, if things went really well, take the whole of China. This plan was supported by some at court, including the sycophant Ren Duo and the strange Yi Shing.

Of course, this plan drew criticisms from the various military commanders like Hu Zan, Ba Daiping and Chen Tiao. They pointed out that sending their army through the Hangzhou Bay was a risky and dangerous strategy, especially to attack the barbarian who was the furthest from their territories. And not to mention the fact that the “distracted” Liang army was literally on their northern border. But the generals found their access to the gout ridden emperor blocked by his Excellency of the Masses, the hated Ren Duo. Once again, Ren Duo skillfully managed to rebuke the generals with well placed accusations of their real intentions in criticizing the Emperor.

Frustrated by the situation, each of the general individually went to meet with the Crown Prince to tell him about these issues. But he had also been taking advises on how to act which contradicted the demands of these officers. His wife Changle had suggested that, for the time being, he simply put his trust in his father, even if this was becoming harder to do by the day. Xiao Bin, his closest brother who now advised him frequently, also told him to be patient. Their father was not immortal, and whatever gripe he had with the current affairs could be addressed once he was emperor. But Xiao Tung could not simply abandon the generals and tried to get their point across. Sadly, his meetings with his father were a complete failure. At one point, a disgruntled Emperor Cheng simply told him

“What did I do to deserve such an unworthy son?”

Emperor Cheng’s opinion of his grandson was barely superior, only made better by the fact that the young man had time to improve. Xiao Gong had reached the age of sixteen as the invasion of the barbarians was being prepared. The oldest son of the Crown Prince and the Crown Princess, he was not only expected to one day succeed his father as emperor, but was also the grandson of the fearsome Budugen the Great. While Xiao Tung had grown up refusing to become the same man as Emperor Cheng, Xiao Cong had always idolized his father. This led to him being able to get a far better military education than his father, having actually been taught in tactics and military strategy. But for all the love he received from his parents, Xiao Cong proved to be a dull man with little imagination or creativity. Not exactly the smart man that his grandfather was. In a sad repeat of the previous generation, Xiao Tung would start to look at his son with some disappointment, though in his case paternal love never disappeared.

The whole debates over the southern campaign were rendered moot when a group of envoys arrived from the barbarian chieftain a month within preparations. Yan Dayu had reasonably come to the conclusion that he had no chance of ever fighting off the Chen Imperial Army, and so chose to willingly submit as a tributary of the Chen. Which meant that there was no need for a war, and thus no excuse to send an army in the Hangzhou Bay to seize Yang Province. This whole schemed now fell apart because the first step proved too successful for its own good. And at the end of the day, Emperor Cheng could only blame himself for this success.

Of course, he didn’t blame himself. His pride would never allow him to admit his own wrongs, even while he had such a sense of justice and responsibility. Instead, he turned his attention toward the generals who had been trying to hinder his various plans this year. And at the end of the day, he chose to settle on Chen Tiao, the most loyal of them all. He decreed that the old man was to be replaced as administrator of his commandery and lose his newly given Marquisate.

But Chen Tiao saw how this led to the end of Liu Xian’s career. Frustrated by his emperor’s ruthlessness, even toward those loyal to him, the most loyal and longest serving Grand Commandant decided to rise into revolt on the last week of the year. Joining him in his revolt were various official who had all lost faith in the current emperor: Chen Gongwei, the general who had helped Ba Daiping defeat the peasant uprising, Luo An, the excellent Excellency of Works who was replaced within a year of his appointment, and Liu Xi, an advisor of the Emperor who was now disgusted by his cruel, ruthless and tyrannic rule. And they all rose up with one goal in mind: to save the Chen Dynasty, Emperor Cheng needed to go.