219: THE FIRST DAYS OF THE LIANG

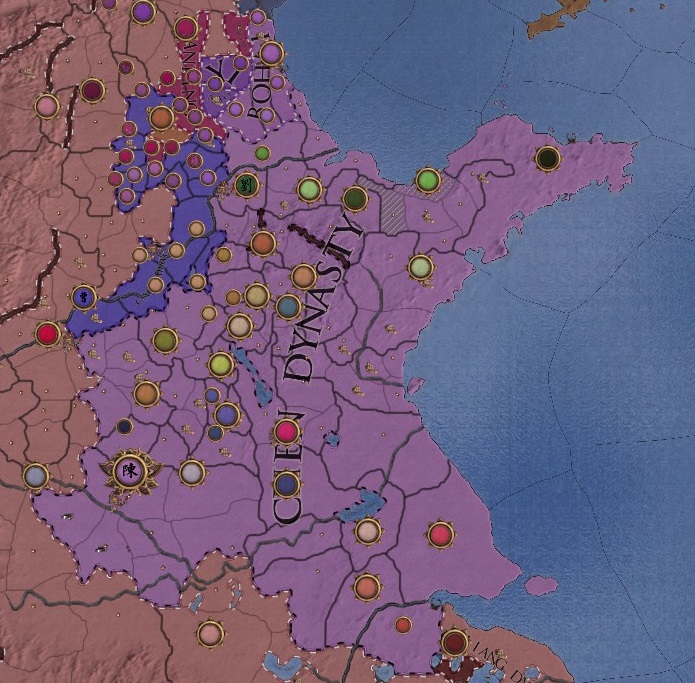

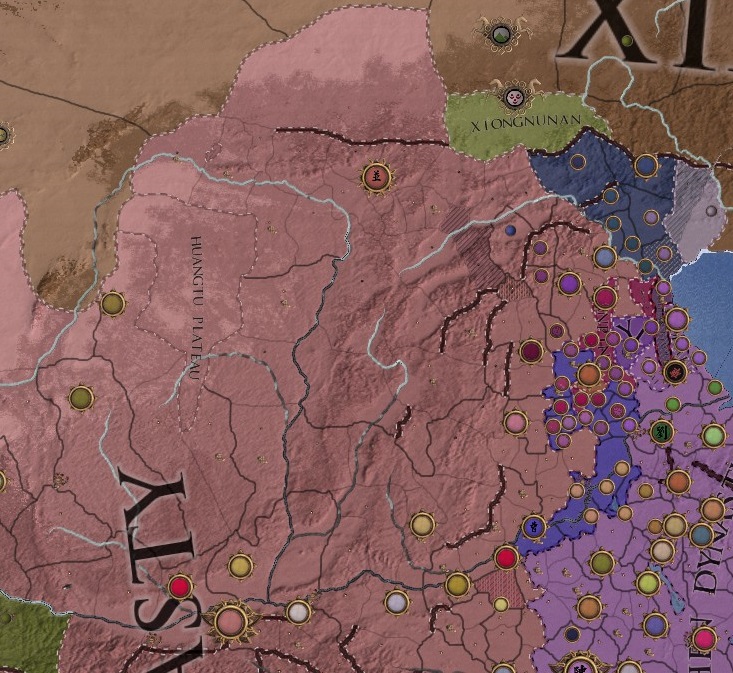

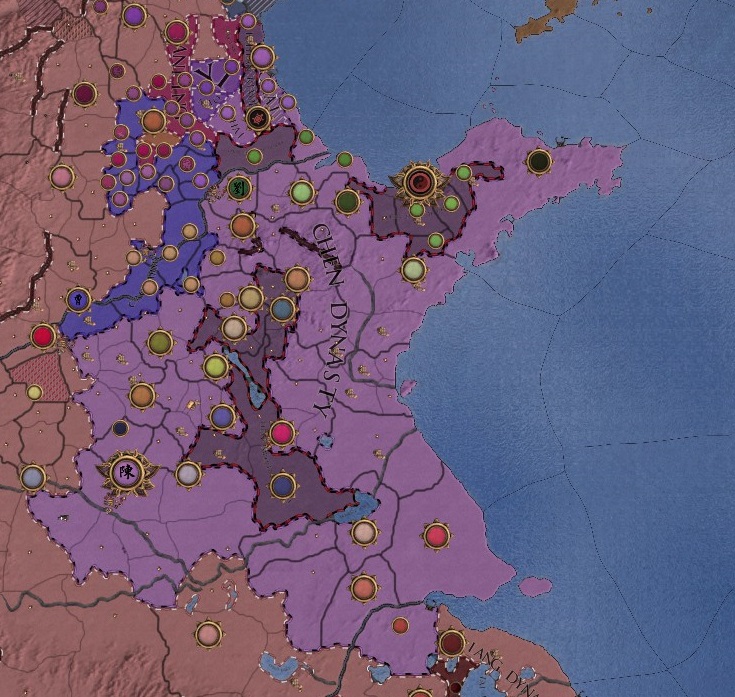

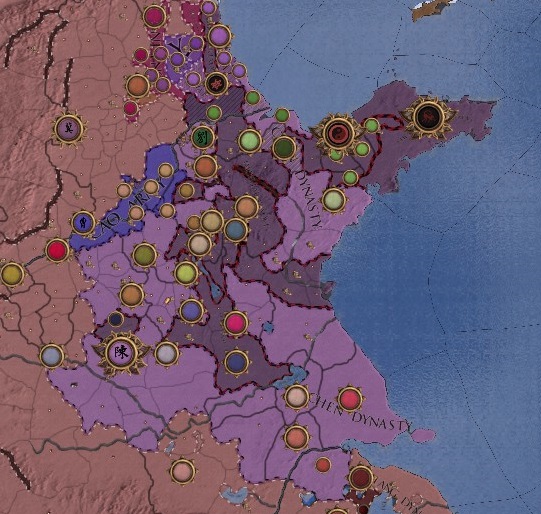

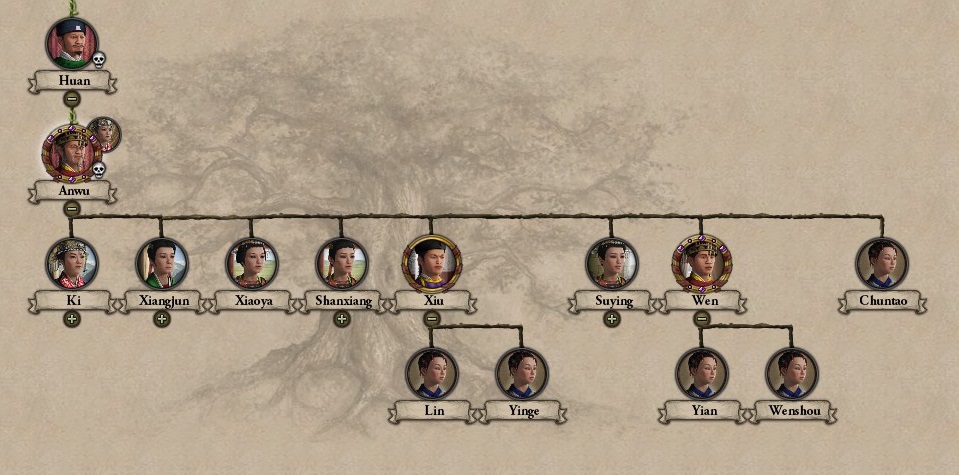

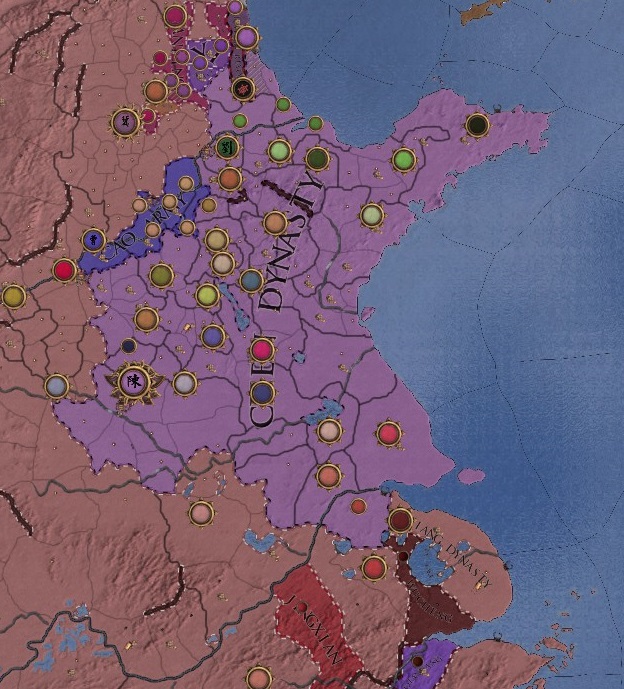

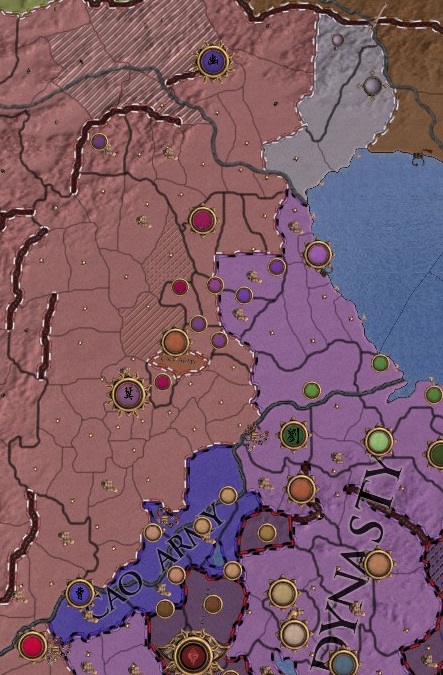

The Han Dynasty was no more. The Liu Clan had lost the Mandate of Heaven through their inability to protect the people and bring peace to the Middle Kingdom. With the exception of Emperor Qianfei, none of the last Han emperors had proven incapable of even attempting to save the Dynasty. And now the Han was no more. The Mandate of Heaven had passed to someone more worthy. Emperor Anwu of the Liang Dynasty was now the legitimate ruler of the realm. Already he had brought a large swath of China under his rule, though the eastern coast still evaded his control. But it didn’t matter. This was a new day, a new age. Yao Shuren, now Emperor Anwu, had no qualms about forcing these warlords to bend to his will. The future was his, and history would remember him as the great unifier of China.

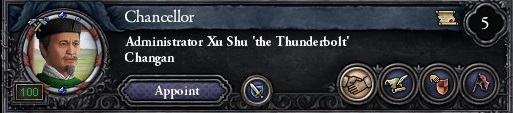

But first, he needed to lay the groundwork of his new imperial regime. While he had spent the last few years conquering territories and bringing the deficient Han bureaucracy under his heel, he still needed to transition it into the Liang state apparatus. This would prove to be an easy task, as he had already put most of his pieces in place before his usurpation of Emperor You. Most of his advisors retained the ranks and offices that they held under the Han, although there were some notable promotions. Xu Shu became Excellency of the Masses, although he remained head of the Censorate and Minister of Justice in the process. Ren Duo became the first Liang official to be Excellency of Work, though Emperor Anwu only kept him until he found a proper replacement. The scholar Duan Zuo became the Imperial Grand Tutor, which gave him greater access to the potential heirs.

But more importantly than anything was the choice of Chancellor. The Chancellor was the highest court office, a position that under the right circumstances could ensure incredible power, as demonstrated by Emperor Anwu while under the Han. Many expected the military minded emperor to appoint one of his generals to the office, ensuring a war focused government that would thrive to unite China. But the Son of Heaven was more focused on the long term. He needed an official that would help him build solid foundations for the future of his dynasty. The Emperor was currently fifty, with his best years now behind him. If he was to pass away before his work was done, then he needed strong officials to continue his work and advise his heir, especially since he had yet to settle on which son would succeed him. Appointing a general, while useful on the short term, might just lead to the new Chancellor following in his footsteps once he was gone. He did not need someone usurping his new Dynasty. So he turned to a man that had proven to be reliable, yet completely uninterested in imperial politics. The scholar Pan Zheng, who had once only wanted to be left alone in his home to study, was now made the first Chancellor of the Liang Dynasty. And of course, he was not allowed to refuse.

In the week after his ascension to the jade throne, Emperor Anwu summoned some of his followers. Some were his oldest, like Hu Zhen, other were among his most loyal, like Cheng Pu, and some were just people he could not ignore, like Xuan Su. One of the benefits of being emperor was that he could now reward his followers with titles of nobility, promoting them to marquis, or even duke or king (though he was smart enough not to hand the very titles he used a stepping stone to usurp the Han). First was Xu Chu, the General who Manifest Might, who was rewarded for his “handling” of Emperor Qianfei’s armed revolt with the title of Marquis of Lingxi. And for Mo Jie, who had served Yao Shuren for two decades by now, he was given the rank of Marquis of Yong.

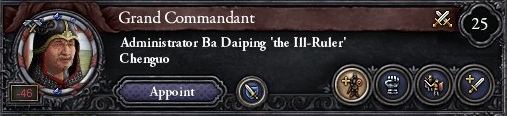

But what Emperor Anwu had hoped would be a spectacle of his generosity turned into an embarrassment when came the turn of the two old generals Cheng Pu and Hu Zhen. Cheng Pu was by far his greatest general, serving as Grand Commandant of the Imperial Army for his services, while Hu Zhen had been his oldest supporters, helping him all the way back when they served under Guo Si. Hu Zhen, either suspicious of this reward or simply showing his deteriorating mental state, laughed and refused the title. He expressed that if he had wanted a reward, he would have asked for it years ago. Cheng Pu also refused the honors. He had no son to continue his line, no heir whose career would benefit from his promotion. And he was in his sixties now. He did not want people to believe that he worked so hard not out of loyalty, but because he sought a noble title. Embarrassed by his officers’ firm refusal, Emperor Anwu decided that it would be safer to avoid further embarrassment, ending his plans to reward the rest of his followers. This refusal would prove Cheng Pu’s last act at court. A month after the founding of the Liang Dynasty, the Grand Commandant died at the age of 65, ending a long career of military service, first under Sun Jian and then under the Emperor.

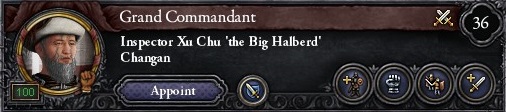

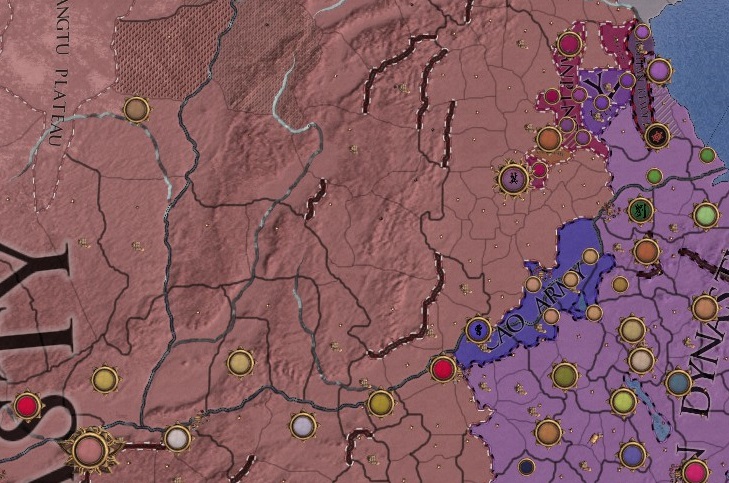

The end of the promotions did not sit well with everyone, of course. Xuan Su had expected to be made marquis, but now he was left miffed at what he perceived as a snub. Cheng Pu and Hu Zhen had just ruined it for everyone. Thankfully, the death of the old general proved an opportunity for the Governor of Bing Province. While he was already an advisor to the Son of Heaven, he now had a chance to gain control of the Imperial Army. Xuan Su could smile at this thought, especially as there weren’t a lot of other options available to the Imperial Court. Xu Shu, while a competent strategist and a beloved follower of Emperor Anwu, was already serving as Excellency of the Masses and Minister of Justice. Xu Chu was a restless beast, clearly unequipped to handle such an important office. Hu Zhen was 73, clearly to hold to be trusted with such an important office.

But what Xuan Su didn’t take into account was that the Emperor might not see the need of an excellent Grand Commandant, as he could handle military matters by himself. He was certainly not going to hand over such an important office to an untrustworthy subordinate like Xuan Su. Instead, Emperor Anwu tapped in Xuan Su’s southern rival, Administrator Yang Xiu of Hedong. Over the years, Yang Xiu had done just as Xuan Su and conquered neighboring commanderies, now holding four of them and making a wall on Bing Province’s southern border. More annoying to Xuan Su was the fact that two of Yang Xiu’s commanderies should have been under his authority, but Emperor Anwu allowed it to keep the governor in check. And now the rival, who was not even a great general, was given command of the Imperial Army. Xuan Su had come to be promoted, not snubbed. Yet he left empty handed and frustrated, and there was little he could do about it.

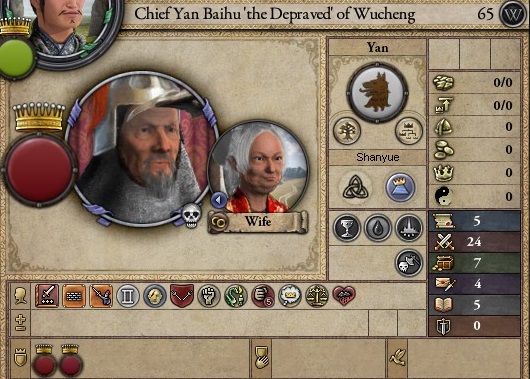

This new appointment proved an opportunity to reshuffle another office, that of the Excellency of Works. Ren Duo had previously served as Yao Shuren’s Chief Steward for years, but had only gotten the position because he was one of the few Sili officials to support him when he conquered the province. But Ren Duo had also shown to be unable to do his job efficiently, and even had a mental breakdown two weeks into the Liang Dynasty’s existence. This had convinced the Emperor that the man needed to be removed. When it came to choosing a replacement, Emperor Anwu decided to appoint one of his former enemies. Best of cases, it would mollify him, and worse case scenario, it would allow the Emperor to keep an eye on the problematic subordinate. Appointing Xuan Su was far too risky, instead choosing the old Shao Wengjie. Shao Wengjie had become a small warlord following the collapse of Gongsun Zan in 206, and had only been brought under heel a year ago. Giving him such an important office should convince him to accept the new authority of the Liang Dynasty. Hopefully.

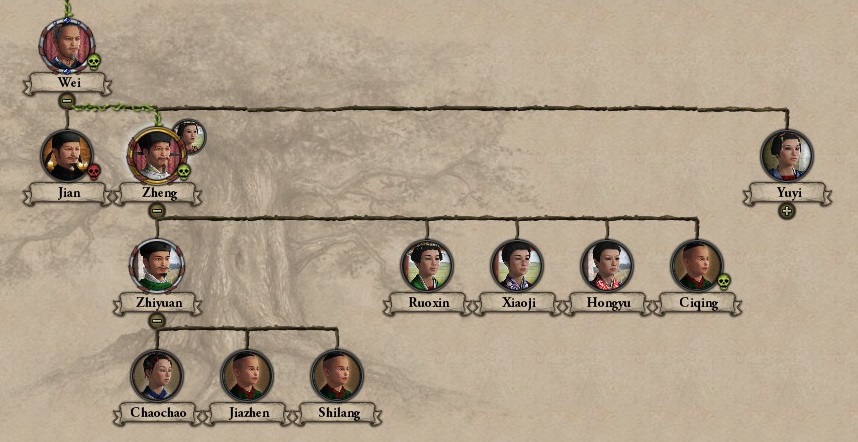

This series of appointments, handing of titles and embarrassments were quickly forgotten when scandal broke out at court. The second prince Yao Yuan felt sick in late April 219, forcing him to be bedridden for a few days. His mother, Consort Liang, spent days by his side to ensure his safety. The imperial doctors were sent to watch over the boys. They quickly identified that the boy was suffering from pneumonia and were able to administrate a successful treatment, ensuring that the young prince’s life was no longer under threat. But Prince Yuan decided to use this sickness against his older brother, who he envied for being the heir presumptive. The thirteen years old told his mother that he had been eating a meal with his brother before he felt sick, heavily implying that he had been poisoned. Consort Liang, who trusted her son’s word, spat insults in the corridors of court, with maids now whispering that the first prince might have tried to murder his younger brother out of jealousy.

And this was not some farfetched theory. Tensions over succession have been brewing for a few years now, with many officials backing Yao Yuan over the issue, as they felt that the younger prince would be more malleable. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that Emperor Anwu had yet to appoint a Crown Prince. As the eldest son, Prince Xiu could expect the position out of Confucian principles. But his relationship with his father had been drastically deteriorating, in part due to both men’s ambitious nature. Adding to this the court’s growing support for Yao Yuan, and it was no surprised that the older prince was getting paranoid.

While he had not poisoned his brother, he had indeed eaten a meal with him. Yao Xiu feared that his father might use this as an opportunity to remove him from succession, whenever he was guilty or not. So Yao Xiu went on the offensive, tirelessly attacking Consort Liang over her accusations in public fashions. But this lack of restrain at court did nothing to gain him points. Emperor Anwu put a stop to these accusations before it spread too far, unwilling to see such baseless rumors overwhelm his court. He trusted the doctors and declared that Yao Yuan was recovering from sickness, not poison. Any further talk over the issue would be seen as slander against the Imperial Clan. This killed the whole affair, but it had the intended effect. Yao Xiu came out of this looking for the worst, his place in the succession ever the more fragile.

Since the imperial succession was now being discussed, Emperor Anwu decided to deal with one lingering issue that came from the abolished Han Dynasty. Liu Zicai, formerly the Emperor and now the Duke of Yanliang, still lived in a mansion close to the Imperial Capital. In exchange for the abdication, Emperor Anwu had promised to Lady Liu that she would not be harmed and that she could live with her son. While he intended to keep his promise, he also left himself a loophole in this contract to tie up loose ends. After all, he had never promised to keep the former emperor alive. The survival of the boy was too much of a threat to his new regime. In early May, he sent orders to the soldiers guarding the former Imperial Family that the boy needed to die. The soldiers entered the house, separated the child from his mother and stabbed him multiple times. Liu Zicai, who had been the last emperor of the Han Dynasty, was only 7 at the time of his death. He had enjoyed less than two months of peace after abdicating the throne.

The death of the former emperor was shocking, especially the fact that Emperor Anwu didn’t even bother to hide his involvement. To him, it was not like he had any reason to hide it, although he did burry the boy as an emperor and bestowed him the posthumous name of Emperor You. The threat of a Han restauration around Liu Zicai was simply too great to be ignored. Anyone who cared about bringing peace to China would see that. And he was right. At least for the time being, the death of Liu Zicai caused no issue whatsoever. In fact, the death of the young boy marked the return of peace in the Imperial Capital. Scandals and disputes stopped, with the court finally working toward building the dynasty that their monarch envisioned. Emperor Anwu and his Chancellor Pan Zheng played a big part in ensuring that everything ran smoothly. Three months after the Liang Dynasty had been established, it seemed solid enough that the Son of Heaven started to look at the remaining warlords, planning in his head how he was going to unify China.

But in June, news arrived of a peasant revolt in the south of Jing Province. Since its conquest, the province had been managed by Wang You, and old an unimpressive official who had only been appointed to appease the followers of the late Liu Siyuan. In his defense, Wang You was hardworking in his duties as governor and humble in his service to the newly created dynasty. The problem was that he was proving a bit too conservative in his spending policies. He amassed the wealth through taxes and sent most of it to Chang’an, but rarely any of it went back to the people. Now, he believed that the dynasty would make better use of this wealth than Jing Province, but to the peasantry this was just unwelcomed taxes. So a few thousands of them rebelled.

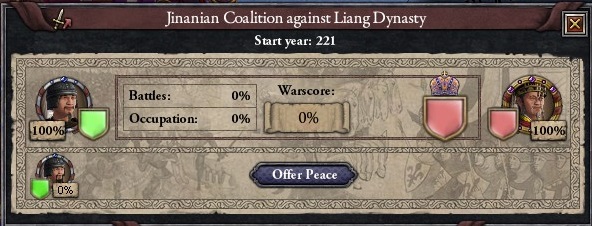

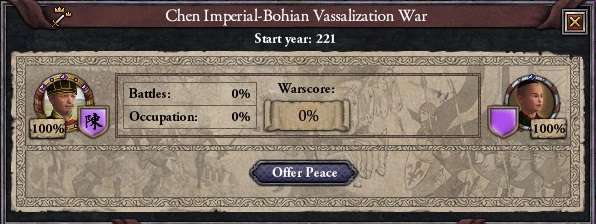

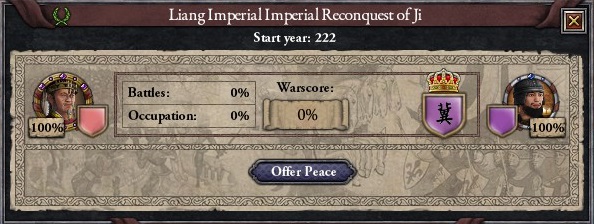

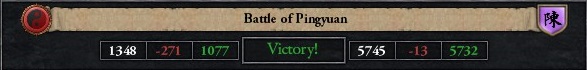

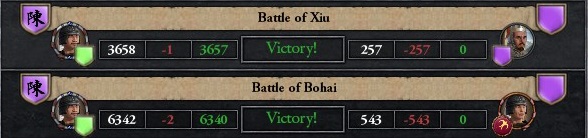

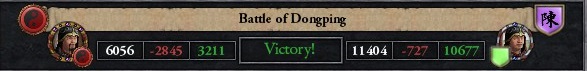

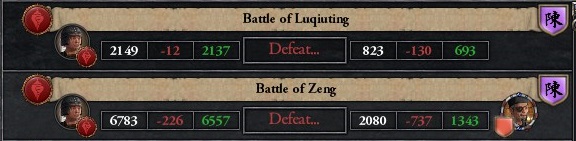

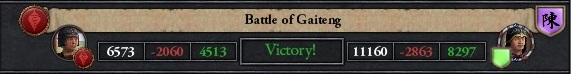

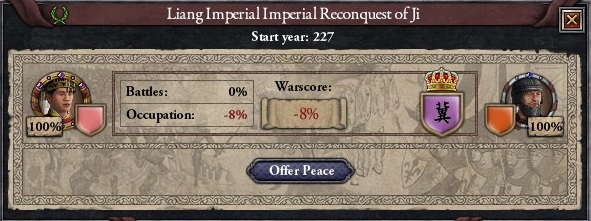

Wang You, as always, panicked at this first sign of opposition. His fears were heightened by the fact that the rebels didn’t explain why they were revolting, simply assuming that it would be obvious. This led to some wild theories. Were they Han restorationists? Were they trying to put back Liu Siyuan’s son in charge of Jing Province? Or maybe one of the Jing generals who had submitted to Yao Shuren was now making a move to claim the province? But while people started to panic at this first opposition to the Liang Dynasty, Emperor Anwu simply smiled. He did not expect peasants to have some grand political agenda and guessed correctly that they mostly disliked Wang You’s management. But instead, he declared that this revolt was caused by “treasonous agents” from Yang Province, accusing the Lu Clan of trying to “undermine the peace and stability of the Dynasty”. Clearly, this attack against his state could not be tolerated. Clearly, retaliation was in order. Clearly, Yang Province had to be brought back under imperial control.

_______________________________________

PS: So I had some time to write a chapter, might be able to write 1 or 2 more before I return into my thesis writing. I’m sadly not out of the woods yet! But I am getting a little bit more free time.

- 4

- 2