225-226: The Civil Emperor

225-226: THE CIVIL EMPEROR

Yao Yuan had now succeeded his father as the new emperor of the Liang Dynasty at the young age of nineteen. While he was an apt courtier who knew how to maneuver in the imperial web of intrigues, shown in particular by his ability to secure the succession, he was not the most qualified heir. His only office previous to his ascension had been as Minister of the Imperial Clan, a task incredibly easy when you have little to no close relatives. But even so, the young monarch now hoped to continue his father’s work and help the dynasty prosper. Sure, there would be critics, but clearly, they could simply take his place since they were also sons of the late Emperor Anwu. Oh wait! No, they weren’t!

Well, one man could answer this with a confident yes: his older brother Yao Xiu. Prince Xiu had been exiled by his father almost five years ago, sent to administrate a small county on the coast to be forgotten. Except that he proved an able and competent administrator, leading him to gain supporters, which only increased his resentment toward their father. Emperor Wen had to nip this potential threat right from the start if he wanted his reign to be stable. But seeing how the stick had failed during his father’s reign, the new emperor chose to use the carrot.

He recalled his brother to Chang’an, declaring his fraternal love for his half-brother and asking for his help. He appointed him as the Governor of Liang Province, even going as far as giving him their father’s old headquarters in Tianshui as his provincial capital. Yao Xiu was also made Chief Architect, with the duty of building the Imperial Mosoleum of their imperial father in Tianshui. This task should keep him occupied for at least half a decade. But just to be safe, Emperor Wen quickly followed this appointment with the announcement that he officially declared his brother as his Crown Prince. Yao Xiu would be the heir of the Liang Dynasty. And if Emperor Wen eventually had a son, then that son would be passed over in favor of his brother (though in truth the Emperor hoped to be secured enough to change the succession by that time).

This was of course quite dangerous. He was giving enormous new powers to his brother, who was now the heir of the Liang Dynasty and in control of the province from which their family originated. Yao Xiu might use this to plot an overthrow of Emperor Wen. But surprisingly, it worked perfectly. The now Crown Prince Xiu was satisfied (for the moment) to eventually inherit what he believed to be his birthright. In the meantime, he was given ample responsibilities to prove his worth. Even more surprising, the two brothers would develop a tight bond between themselves. While they had been pitted against each other over succession, it seemed that with their father now gone the two brothers found themselves getting along quite well.

With this potential enemy turned close ally, Emperor Wen then turned to other family members. He quickly issued a decree promoting his mother Empress Liang to the rank of Empress Dowager of the Liang Dynasty, the first woman to hold the position. The thought of an empress dowager lording over a young and weak-willed emperor certainly worried the officialdom, but they had nothing to worry about. Not about the weak-willed part, as Emperor Wen was indeed the sort to bend when confronted. But Empress Dowager Liang simply did not have the skills nor the will to be the puppet master of her son, who was simply far more politically apt than her. The Empress Dowager would mostly remain away from court affairs, only getting involved in the familial and marital affairs of her son.

With Empress Dowager Liang removing herself from the scene, this left the stage ready for the new Empress Xu. The new empress was the daughter of the longtime Liang loyalist Xu Shu (who had been dismissed from Chang’an at the start of the year by Emperor Anwu). Most people who met the young woman described her as a proper and patient lady who occasionally blurred her honest thoughts when she should have kept them to herself. Thankfully, she knew to do this only in private and with people she knew well enough to forgive her honesty.

But through her calm and composed demeanor, Empress Xu was suffering from frequent bouts of depression. While the rigidity of her duties was slowly getting to her, the main reason behind this was her inability to produce a child with the Emperor. She had been raised to be a proper lady, worthy of her father and worthy of being married within the Yao Imperial Clan. But she had yet to produce an heir to her husband, or a child for that matter. Wang Wenjun and Pan Xiaoji had both given him daughters, so why couldn’t she fulfill her role? It didn’t help that she was quite shy when it came to sexual relationships, something that the concubines didn’t have to worry about. And then there was the attitude of the Emperor. Not in a particular haste to produce a son with his brother right there to inherit, Emperor Wen found himself even less interested in Empress Xu due to her depression. This only exacerbated her condition.

As for his main advisors, things were definitively more tense than expected. Emperor Anwu had fired many of his old comrades in order to ensure that they wouldn’t had too much power over the new Emperor. The new advisors would be less influential and thus more likely to support Emperor Wen. Slight hiccup in this plan: none of them liked the Emperor (with one notable exception). Chancellor Jin Xuan didn’t like the sarcasms of the Emperor nor his lack of empathy. The Excellency of Works Hu Duo was simply paranoid and didn’t trust this scheming young emperor one bit. The Excellency of the Masses Ren Duo had once served under Emperor Anwu and didn’t like being bossed around by a boy under twenty, even if they had similar personalities. As for the Grand Tutor Zhang Zhongwu, they just didn’t get along, though neither the Emperor nor his scholar dared to start a confrontation over this.

To summarize, Emperor Wen was in a peculiar situation. His mother had removed herself from politics instead of assisting him, his wife failed to produce him a son, his brother turned ally had been made too busy to help him in Chang’an and the advisors left behind by his father hated his guts. This was not the ideal start for the reign of a young and inexperienced emperor. Thankfully for Emperor Wen, he had the full loyalty of one member of his council, and a critical one at that: the Grand Commandant. Zhang Dezong had been promoted by Emperor Anwu because he was a good general and little else. He had no personal ambitions outside of fighting for the Dynasty, nor could he prosper at court due to his lack of social skills. As long as the Emperor allowed him to lead campaigns, Zhang Dezong would always be there to side with Emperor Wen, shielding him against threats to his authority.

Many officials either sent gifts and tributes to Chang’an or visited in order to get in the good graces of their new monarch. This was certainly at the forefront of Xuan Mei’s mind when he was made aware of the succession. He needed to ensure that he was on the good side of the Emperor, that he could use him to gain control of You Province as his father Xuan Su had done. He was the rightful heir of Xuan Su and would reclaim what his father had once controlled, bringing back the Xuan Clan to the forefront of Liang politics! But he was also warned that the Emperor might use his presence in the Capital to arrest him and remove him from power. Fearing this real possibility that Emperor Wen did indeed contemplate, he instead chose to cowardly send his wife to present the gifts to the Imperial Court.

Han Huidai was the youngest daughter of Han Fu, the last Han appointed Governor of Ji Province before it was seized by Gongsun Zan. Han Huidai had been married to Xuan Mei as part of one of Xuan Su’s wild plans to lay some sort of claim on Ji Province. Lady Han was known for being quite the looker, which coupled with her kind heart and surprisingly upfront personality made her well liked among her peers. She certainly caught the attention of Emperor Wen when she showed up in Chang’an with gifts. Officially, her husband couldn’t come because he was defending the border, but she bluntly said that he was simply too scared to make the trip.

Immediately, Emperor Wen started to fall head over heel for Han Huidai. He arranged multiple audiences with her, officially to ask her about the situation on the northern border and to learn more about these areas he had never visited. Soon enough, he started to make visits to the house she was living in while in the Capital. Han Huidai certainly welcomed the attention, and being courted by the Emperor certainly felt better than that hunchback she had for an husband. The Emperor then used excuses and ploys to convince her to stay longer and longer, eventually stretching her stay to six weeks.

But in the end, Emperor Wen got cold feet and put an end to their relationship before it turned physical. He realized that stealing the wife of one of his governors was not a great way to start his reign. More than likely, it would leave him with an amoral and debauch reputation, which he did not need. His wife and concubines had also been complaining once they noticed that his attention was clearly elsewhere. Empress Dowager Liang even told her son “Whoever you are fucking, she is either a whore or your concubine, but choose quickly.” A bit taken aback by his mother’s foul language, he answered with “And now I know what use my father the late emperor had for your fool mouth, if this is all you think about.” But for all this crass exchange between mother and son, it did bring Emperor Wen to the conclusion that the fallback for bringing her in his harem would be too much. Han Huidai also agreed, as she had just given birth to a son named Xuan Shen the previous year. She couldn’t abandon him and her daughters like that. Their blossoming romance thus came to a quick end through their own accord.

Seeking a distraction from his broken heart, Emperor Wen decided to bolster his prestige and new regime by surrounding himself with his father’s former associate. This was despite the fact that his father had pushed them away to avoid these officials getting to close and influential with Emperor Wen. He appointed his father-in-law Xu Shu as Minister of Justice, hoping to eventually make him one of the main supports of his reign. He sent orders to Xu Chu, Governor of Yi Province and Marquis of Longxi, to leave for the Imperial Capital to be handed a command on the campaign against Zhao Yun (which was still being fought by Grand Commandant Zhang Dezong and Xu Shu). He even released the long-time scholar Duan Zuo, even though he had been arrested for his crimes and was going to be executed by Emperor Anwu once the campaign ended. In an attempt to link his regime to that of his father, he was bringing back some of the most problematic men that Emperor Anwu had attempted to push aside.

But the most important of these rises back to power was that of Mo Jie, who had fell from grace after the adoption of his barbarian son Mo Duo. The 65 years old men had spent the last few years as the Governor (and Marquis) of Kong, simply doing his best to improve the life of the local people. But now Emperor Anwu wanted to show that he was his father’s successor, which meant bringing back one of his oldest followers. The paranoid Hu Duo, who had replaced Mo Jie as Excellency of Works, found himself removed from office to make place for the old man. Hu Duo would come out of this frustrated and with a grudge against both Mo Jie and Emperor Wen.

Of course, many protested the appointment, and the Emperor almost caved. Mo Jie tried to say that he was fine with living the rest of his life away from Chang’an, but most perceived it as an inspiring speech that convinced some officials that Mo Jie might be the man for the job, including the Chancellor Jin Xuan. He was immediately made the new Excellency of Works, a position he readapted to with ease. But this time would be different. Previously, Emperor Anwu had been the driving force behind the policies, always hindering or denying Mo Jie’s ideas to reform the realm and avoid the tyranny he once rebelled against. But now sat a young, inexperienced emperor with no real will to force economic policies (which he barely understood anyway). Now was the time for Mo Jie to reach the zenith of his power and bring his long-dreamed reforms to the Liang Dynasty, reforms that would play a big part in the young emperor’s eventual posthumous name.

Then October came around, only three months after the death of Emperor Anwu. Emperor Wen was starting to feel like he was getting the hang of this emperor business when news came that Zhang Dezong had died at the age of fifty from natural cause. Just like Emperor Anwu, a malaise was followed by a decline of health and the man’s eventual death. And now Emperor Wen’s loyal supporter in the military was no longer here to protect his liege. This was certainly a problem, as Emperor Wen did not receive the same respect from the generals that Emperor Anwu earned through his decades of conquest. And never mind the problem of not having a Grand Commandant to follow his orders. The worst-case scenario would be a violent and angry general who might brutally weight around his power. Then Xu Chu arrived two days later at the city gates.

Xu Chu came back to Chang’an with a furious attitude, still sour at the way he had been fired by Emperor Anwu. He had been summoned back to help with the campaign, which he felt was about damn time. But now he entered Chang’an just as the court was racing to find someone to take over the war for Anping Commandery, as Zhang Dezong was dead and Xu Shu was on his way back to the Imperial Capital to serve as Minister of Justice. And when people saw Xu Chu, they became convinced that he was the solution to this problem. Xu Chu had served as Grand Commandant before. Surely, he would prove a match for Zhao Yun and end this war in victory. Xu Chu, hearing this, was quick to agree that he was the best general in the history of China.

During his first court audience since returning to Chang’an, Xu Chu bluntly came forward and demanded that he be reappointed Grand Commandant of the Liang military. Wary of this old brute, Emperor Wen casually tried to push the issue aside, but Xu Chu insisted, saying that “Your Imperial Majesty is just a brat! Brat should listen to their elders! I can win the war for the Son of Heaven! So I must be appointed now!” In the end, Xu Chu had to be removed by force from the audience, a difficult task that required multiple guards. While some argued that this was an insult to court decorum, Emperor Wen did not have the spine to punish such an esteemed general for his actions.

But then at the following audience Xu Chu came again, demanding that he be made Grand Commandant. His angry demeanor kept hindering the affairs of the state. Now Emperor Wen was starting to be scared of this tall and bulky general, who even in his old age looked strong enough to crush the monarch’s head between his hands. It became worse when Xu Chu tried to force his way into the Imperial Palace to push the issue upon the Emperor. Emperor Wen actually saw the guards trying to block the entrance as Xu Chu attempted to push through. Had Xu Chu been carrying weapons in the court, Emperor Wen could have accused him of breaching the rules of the palace and rid himself of Xu Chu. But either out of wisdom or arrogance (surely the later), Xu Chu had elected to come in simple clothes to force his case. Because of this, he was able to stand in the courtyard as guards spent the night trying to restrain him. This event spooked the Emperor so much that at the next court audience, he shrieked out of panic when he saw Xu Chu entering. The general didn’t have to say a word this time, as Emperor Wen granted his request the second Xu Chu took a step in his direction.

But the second Xu Chu was out of Chang’an, Emperor Wen began to work on a plan to undermine the authority of his new Grand Commandant. Another general sent especially by him would be able to share in the glory of the victory against Zhao Yun. The perfect man for the job seemed to be Feng Desi, the young Administrator of Yuzhang Commandery. Appointed under Emperor Anwu, Feng Desi was loyal to the Yao Imperial Clan and saw himself as its best general. Sadly for Emperor Wen, the man would prove a terrible choice. While he believed himself the best, unlike Xu Chu these assumptions were far from the truth. He was also quite the squeamish man, proving unwilling to be any opposition to the brutish Xu Chu. So much for providing a rival to the Grand Commandant…

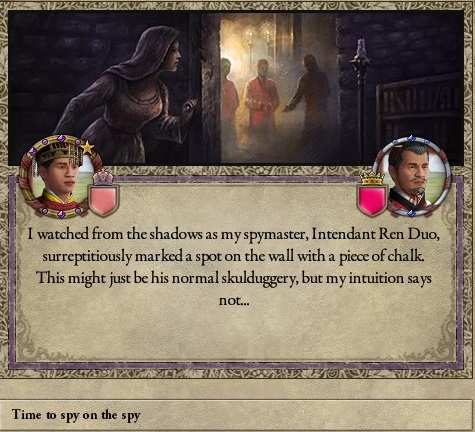

Toward the end of the year, Emperor Wen started to become suspicious of his Excellency of the Masses Ren Duo. The old man had been a follower of his father for more than a decade, yet in the last years of the Han he was pushed aside and removed from the inner circle. Surely there must have been a reason for this removal. Surely, the man had something to hide, something that Emperor Wen could hopefully use to keep him under control or arrest him. It didn’t help that the older official didn’t like being ordered around by the young emperor, with Emperor Wen never forcing the issue to avoid a confrontation. But if he found something, then he might be able to assert some control over this man.

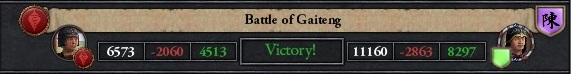

My late February 226, news came to Chang’an that the war was over. Xu Chu had succeeded in his task and annexed Anping Commandery in the Liang Dynasty. Emperor Wen could only sigh in relief as his father’s last campaign ended in a complete victory. But this left the question of what to do with Zhao Yun, who was now forced to submit to Liang authority. Many wanted him to be put to death, but Emperor Wen quickly allowed the general to stay as the administrator of Anping. Publicly, he wanted to show his great clemency and prove that he was welcoming of great men, making sure to give them a place within the Liang Dynasty. Privately, he hoped that eventually Zhao Yun could become a threat to Xu Chu, a threat that could then be exploited. So Emperor Wen spared Zhao Yun, a decision that would come bite him back, hard.

But this joyful triumph was quickly unsettled by Xu Chu’s return to Chang’an in March. He was well received at court and welcomed for his accomplishments, with Emperor Wen making sure to praise the general as much as possible (though few noticed that most of it was sarcasm). But Xu Chu then started to insist that he was the greatest general of the Liang and needed more powers to protect the dynasty. Xu Chu’s advisors had told him that he should ask for the right to lead a potential regency should this ever be needed, and Xu Chu did exactly that. It wasn’t like there was no precedent, as the later Han had many powerful generals acting as the regents for weak or young emperors, though most of these men got their power from being related to the then empresses.

Fearing that he had a wannabe Dong Zhuo in the making (or worse, his own father 2.0), Emperor Wen tried to weasel himself out of this by saying that this interesting proposal would need to be considered in details. But Xu Chu didn’t want to hear this. He wanted this position, and was willing to outright bully the Emperor to get it. As had happened before, Emperor Wen was too scared of Xu Chu to oppose him in person, quickly agreeing to the demand in order to get rid of him. Xu Chu left quite satisfied, having accumulated even more power than he had under Emperor Anwu. Emperor Wen was also aware of this fact, which is why he desperately needed to find a way to hinder the general’s rise.

Stressed by the current affairs of the court, his inability to control his officials and the sheer weight of his duties, Emperor Wen started to eat away his stress. This resulted in the Emperor slowly but surely gaining weight. His entourage started to notice, with the Empress and the Empress Dowager deciding to do something before it got out of hands. At the end of March 226, they came to Emperor Wen and reminded him that he needed to stay strong, that he needed to be there for the people, for the dynasty. Empress Xu proved especially successful in reaching her husband, never overstepping her bounds and patiently reminding him of his duties. And he realized that they were right. It hadn’t been a year since he took over the throne, yet he was already caving under the pressure. His father would never have been like this. How could he face Emperor Anwu after his death if he was unable to keep his cool? Thanks to this intervention, he quickly dropped this habit of stress eating, returning instead to ploting against his officials to secure his position. After all, this was the only thing he was good at.

- 6

- 1