Teaser #06

"I write with my heart broken – broken, torn, trampled on as if it had been stepped on with heavy boots – standing before the fresh grave where sixteen heads with bullet holes in them lay in a line: a house full of “agents provocateurs,” a team of old revolutionaries who were Lenin’s companions and friends. I knew some of those who were executed in Moscow quite well. Their sufferings will one day be measured, and people will be amazed that we could have gone so far, could have descended so low in the fear and hatred of political adversaries who, just the day before, were our comrades. Among these men there is one who, due to his extreme modesty, is little known in the West but who, for the generation of the October Revolution, was both a symbol and an example. He entered history with a tranquil heroism, disdainful of fine words, foreign to any ambition other than that of serving the working class: Ivan Nikitich Smirnov.

Tall, thin, with a rather small head, fine features, an unkempt moustache, his hair short and in a kind of crew cut, his pince-nez a bit crooked, a smiling, gray gaze that immediately revealed the old child full of illusions about life within the aging man. Good-humored, with a kind of sad gaiety at difficult moments, when he would cross his long hands across his legs and look into the void. At times like those his face would suddenly age. But Ivan Nikitch would shake off his torpor, would straighten his shoulders, would look you in the eye with his gentle gaze and would assure you with invincible reason that “the revolution is made up of highs and lows, of course. What matters is to stick with it. And we've stuck with it for quite a while, right?” For him, to “stick with it” meant serving it, giving of yourself with a total lack of self-interest.

A former worker, one of the founders of the Bolshevik Party, I don’t exactly know what road he followed to the prisons of the

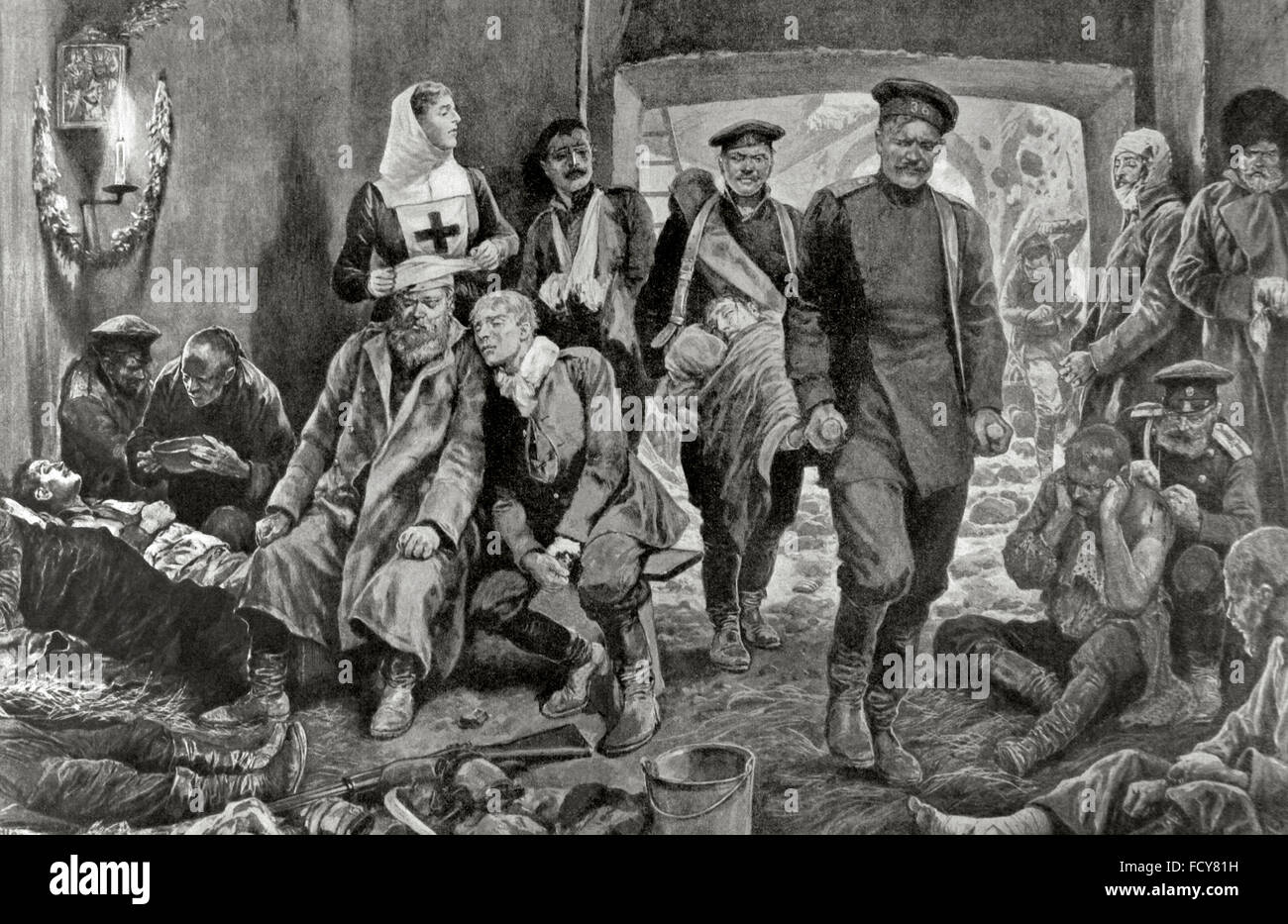

ancien regime. When in 1918 a Red Army had to be improvised in order to carry out the Civil War and resist the Czechoslovak intervention, Ivan Nikitich, who had never held a weapon in his life, hung a Nagan revolver on his belt and, along with Trotsky, took the train to Kazan. The Whites had just taken this city, the front had been pierced, the first Red troops were in rout before corps of intrepid officers. Panic was mixed with confusion; they were lacking in everything and the Republic appeared to have suffered a mortal wound. Moscow sent into that breach, that mortal wound in the Revolution’s flank, a train of volunteers taken from among the best. They arrived in the midst of the rout, allowed their path of retreat to be cut off to show that they wouldn’t withdraw, and, at the tiny station of Sviaysk, not far from Kazan, battled alone against the shock troops of Kapelle. The Red General Staff, with its typists, its sentries, its cooks, all its non-combatant personnel, held out for 24 hours before the machine guns. Trotsky had sent away the train’s locomotive: let there be no doubt about it, we will not leave here. Larissa Reisner, who fought there, dazzling with grace and passion, left some beautiful pages on this episode. “Ivan Nikitich Smirnov,” she wrote, “was the communist conscience of Sviaysk. Even among young soldiers and non-party members his uprightness and his absolute probity impressed everyone immediately. He doubtless didn’t know how he was feared, how afraid we were to be cowardly or weak before him, before this man who never raised his voice, who limited himself to being himself. Peaceful and brave?” “We felt that he would never weaken in the worst moments. We would be calm, our spirits clear; we would ourselves be standing alongside Smirnov, with his back to the wall, being interrogated by the Whites in the filthy ditch of a prison. We would tell ourselves this, lying in a pile on the wooden floor on already-cold autumn nights.” Sviaysk remains a capital date in the history of the Soviet republic; it is there that in 1918 the revolution was saved by a handful of men, and Ivan Nikitch was one of the leaders

When in 1920 the peasants of Siberia, formed in partisan detachments, made the situation untenable for Admiral Kolchak, Lenin recommended that the task of sovietizing and pacifying Siberia be confided to Ivan Nikitich. Smirnov became the Chairman of the Revolutionary Committee of Siberia; Smirnov founded the Republic of the Far East, a provisional rubber-stamp state that permitted the Soviets to avoid war with Japan. Thanks to him the sovietization of the north of Asia, where the Whites had shown themselves to be abominably cruel, was carried out almost without reprisals.

From 1923 Ivan Nikitich belonged to the Opposition, which called, from within the party, for militants’ right to think and, and in the country, for the instituting of worker’s democracy and a fight against the growing, and increasingly arbitrary, power of the bureaucracy. When his expulsion from the party was announced in 1927, he was People’s Commissar for Post and Telegraph. Expelled, Ivan Nikitich passed his portfolio to the successor designated by the party and found himself penniless. An employee at the Labor Exchange of Moscow, the registration service for the unemployed, found before him an old man with pince-nez who made himself known as a precision mechanic and asked for work in one of the factories where he knew, from solid sources, that there was a lack of such qualified workers. The employee filled out a form. “Your last job?” he asked the unemployed worker. “People’s Commissar for Posts and Telegraph.”

The Central Committee didn’t allow Ivan Nikitich to take his place in the ranks in the factory. He was deported to that Siberia which he had contributed to conquering for the revolution. Deportation meant more to him than captivity: it meant inactivity. Ivan Nikitich capitulated in order to again become useful; according to the consecrated term, he made honorable amends before Stalin, and abjured – half-heartedly, for how could it be otherwise – his convictions as an oppositionist, and asked that he again be given the occasion to serve the revolution. “Our disagreements,” he said among intimates, “are serious and profound. But what is important above all is to construct new factories and set them in motion” He was given the leadership of the new automobile factories in Nizhny-Novgorod. It was there that they came to arrest him in December 1932 as “suspected” of heresy. Without a doubt, he thought, saw, and judged, and even if he said nothing he didn’t consent to what he saw. The conscience does not abdicate (though we sometimes do it violence). In order to execute him they attempted to impute who knows what responsibility in the assassination of Kirov. But the day Kirov fell Nikitich had already inhabited a prison cell in Souzdal for two years!

While at the other end of Europe a General Franco is sticking a knife in worker’s Spain, to spill the blood of such men, the blood of the founders of the USSR, is a strange, horrible aberration!"

-Victor Serge.