Bold of you, by the way, to be committing to a long AAR on a newly released Paradox DLC straight off the presses, and one with such a huge overhaul of surely fragile base mechanics at that.

Who dares wins

But yes, I have thought about it, so I am actually contemplating if I am to start the "proper" AAR around the release, or when I am familiar with the mechanics and the game has

less no bugs. I am currently leaning toward the former, which will also make for a more challenge when it comes to overthrowing Stalin and being in a world war.

I wonder how much this would lead to the Provisional Gov't's eventual downfall. My initial guess is it wouldn't have made a huge difference since they couldn't enforce most of their laws anyways, but I suspect they regretted pardoning all political crimes.

I think so, but they were caught between a rock and a hard place. If they did not release political prisoners they would be seen as just another version of the old regime, remember the whole Kornilov affair. It would just play right into the socialists in the Soviet, and would deligitimize the Kadets and liberals who advocated for political freedom and had members that were political prisoners too.

And every party leader gets a Dacha on the Black Sea?

There is no corruption in the glorious soviet society! As a sidenote, I think it is funny that some literally say there was no corruption in the Soviet Union, and then use Stalin as an exmple as he only had his uniform and tobaccoo. That gloss over his personal Dacha, that was oficially state property, that only he used and was refurbished several times. Not to speak of that he had a quite lavish lifestyle the state payed for. It was of course not limited to him, but he is used as an anectode for no corruption, but indeed top party members became the new upper class.

Now, will Trotsky do something about this, or does he simply want Dachas of his own?

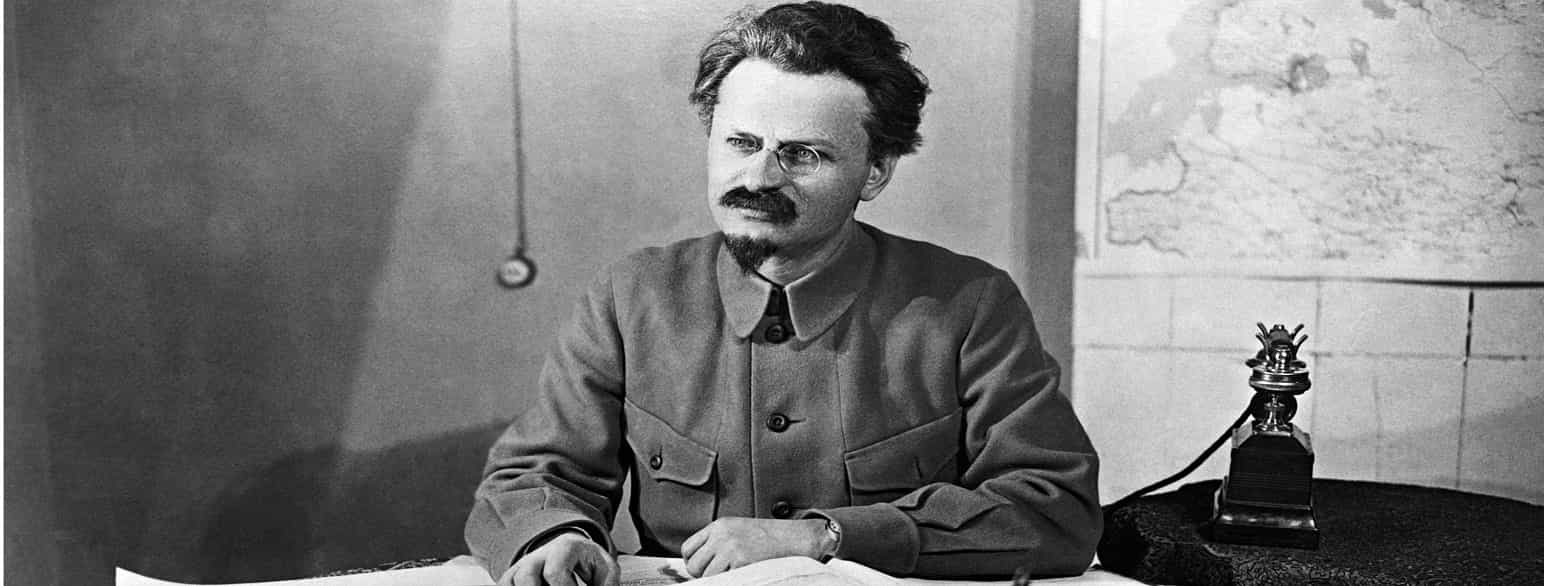

So Trotsky actually loses with Stalin but doesn't have an unfortunate visit with an ice pick. I had thought he would win the power struggle after Lenin's death, but this sounds more interesting.

Ice Picks are still a very real and hazardous object! Especially in Mexico.

Up until 1936 history will be somewhat as in OTL, but with some minor alterations that will be obvious in Book Two, and once Book Three starts. And that is why Trotsky might fail to return as he is plotting his return in a faraway land. And we might even end up with Trotsky dying and someone else taking up the mantle and take the fight to Stalin.

So there will be plenty more episodes of A Game of

Thrones Soviets!

Do you think the Soviets were already trying to sabotage Kerensky's government? It seems like the Bolsheviks ultimately planned to take control, so it wouldn't surprise me.

Indeed they were. Mensheviks and Social-Revolutionaries not so much as in an outright coup. But even then, early on Menshevik-Internationalists and Left Social-Revolutionaries were initially more numerous than the Bolsheviks, and even they supported a revolution. But they set up an alternate power structure, some wanted to sabotage it to make the new government reform into a better society, and others, not only Bolsheviks as this AAR and history gives you the impression of, wanted revolution and get rid of the Provisional Government altogether. To add further confusion into the mix, as you could see several key Bolsheviks didn't want a revolution either. It wasn't until Trotsky and more radical bolsheviks was released from prison (again) coupled with Lenin's writings, but to be honest the action of men that is actually there is more impactful than letters from someone hiding that can be ignored, that they managed to push them (and left Mensheviks and left social revolutionaries) toward revolution.

Because of the radicalization of the Soviets many of the former "moderate" Mensheviks and Social-Revolutionaries, and Popular Socialists (another splinter group of the SR) left the Soviets and instead formed a government coalition with Kerensky. Yes, after the July Crisis Kerensky had a government based upon Kadets, Progressives, SR, and Popular Socialists. Now it should be noted, Kerensky himself was a revolutionary, who wanted to overthrow the Tsardom and old society. The SRs and Progressive Socialists were the heirs of the Narodniks and Agrarian-Socialists (Lenin's brother was hanged for conspiring with them against the Tsar) and was by no means moderate and had decades of experience doing bomb-throwing, assassinations, and so on. But compared to the Bolsheviks, Internationalist-Mensheviks, and Left-SR was even more radical. We will examine this more in the next update, and you will see that the Left-SR might even be more radical than the Bolsheviks and more dominant in the Soviets.

That being said, I am also harsher on Kerensky than I would otherwise be. But he was caught between a rock and a hard place. To the liberals and conservatives, he became too radical and revolutionary, at least he was a socialist revolutionary, meanwhile, as the radical elements of the Soviets became the dominant force he become too moderate and conservative for their liking. And while he formed a government with the broader left, they were now not the leading forces in the socialist movement.

That's something I've always found interesting - the early Volunteer Army was almost entirely officers because the common soldiers weren't interested in fighting the Soviets. That changed of course, as Soviet policy became more clear, but I think it shows how much the old order had failed Russia by that point.

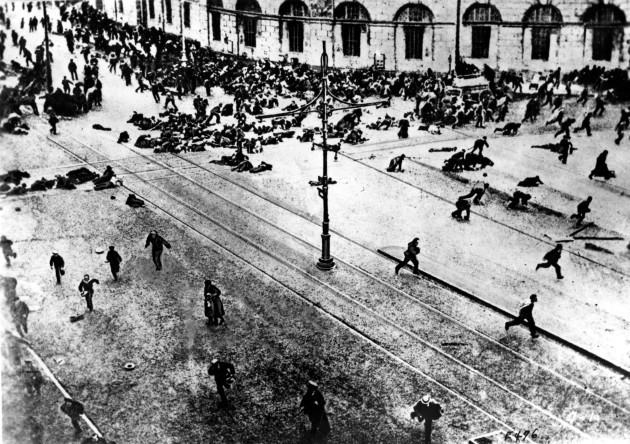

Indeed! And just how fed up they were with the war. They had major supply issues and major moral issues, with famines looming. This topped with memories of everything the Tsar had done for them. That reminds me, during the coronation of the Tsar, he wanted a big party and celebration for the peasants. Everything good so long, only that he did a Travis Scott only that is was even more severe, where depending on sources 1400-4000 people died and was trampled to death with many injured. The Tsar continued the Coronation and the festivities, much to the anger of the population.

Old Russia had failed them, and they wanted peace, bread, and land. Another reason why Kerensky's government became unpopular. He failed to provide for peace and redistribute land and nationalize industries that he promised (remember, he is a revolutionary socialist), instead of continuing the war. Many of the peasant uprisings I mentioned in the chapter were soldiers deserting, executing their officers, and then finding the nearest estate, lynching the owner(s), proceeding to redistribute land forcefully.

/The_Russian_Revolution_1905-5809637e3df78c2c73877a42.jpg)