Kurt_Steiner: Pretty much.

volksmarschall: I don’t think so.

Except...Jackson’s own party is disunited in taking any action in Southeast Asia. Heck, Scoop is getting more support from the Republicans.

jeeshadow: You’re right. In terms of a political convention melting down, it’s hard to compete with the police beating the crap out of protestors in the streets and the Mayor of Chicago shouting obscenities at Abe Ribicoff.

You’re also right about McGovern and Wallace having a clearer base of support than Scoop does.

As for China being provoked, we will just have to wait and see.

Off the top of my head, Jackson’s predecessor John Sparkman had pushing through Congress a conservation agenda, establishing NASA, starting the national highway system, peacefully resolving the Suez Canal dispute between England and Egypt, and keeping Castro from going completely over to the Soviets as his major accomplishments. Scoop pales in comparison.

El Pip: How do you avenge the Maddox and defeat the Vietcong? The same way you solve all problems: throw plenty of young men at it.

Jackson has had a long-term plan. It’s stabilizing South Vietnam enough militarily that America doesn’t have to worry about her collapsing. He doesn’t want a single united Vietnam. The problem with his plan is that the other side does.

The plan for North Vietnam after US ground troops have invaded is to leave quickly and hope the Chinese don’t notice their presence the way they noticed America’s presence in North Korea during the Korean War.

A plan for the corrupt pit that is the South Vietnamese government? Whoa, whoa, whoa. Slow down there, El Pip. You are asking too much of Jackson.

SirNolan: Pound of flesh? I don’t think I have heard that phrase before.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

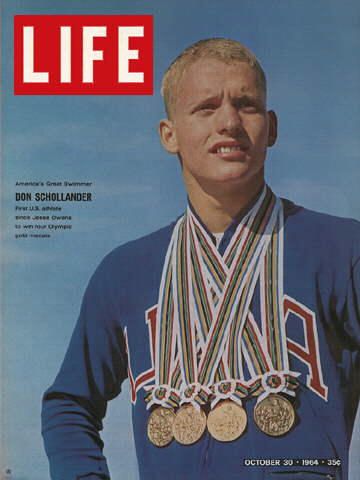

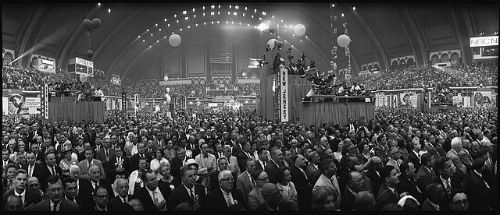

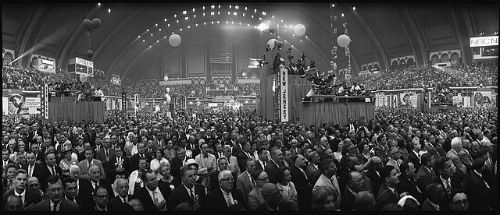

The 1964 Democratic National Convention

On Monday, August 24th, 1964, all eyes were on Atlantic City, New Jersey as the resort city hosted the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Incorporated in May 1854, Atlantic City was best known for her oceanfront boardwalk, inspiring the board game “Monopoly”, and hosting the annual Miss America Pageant. Now in late August, Democrats gathered at Convention Hall – which could seat 15,000 people – to quadrennially nominate their Presidential ticket. Elected President in 1960, Henry M. Jackson should have been a shoo-in for re-nomination in 1964. After all, no incumbent President had been dumped by his political party after one term in eighty years. Unfortunately for Scoop, he headed into Convention Hall from a position of weakness. He was an unpopular President whose three-and-a-half years in office had been troubled ones. Other than the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1963, Jackson didn’t have much legislative accomplishments to point to. His strong push for civil rights, while earning him praise and admiration from African-Americans, had shattered the Solid South which was the electoral bedrock for the Democratic Party. Liberals were angry at him over his hawkish handling of Vietnam, his eagerness to pour money into defense spending (symbolized by the infamous Dyna-Soar III flop), and his lack of action on negotiating a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union. Jackson had also been wounded politically by the 1962 steel strike and a huge scandal at the Department of Agriculture which managed to dwarf the Teapot Dome Scandal of the 1920s. Another scandal forced Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to resign from the Administration in early 1964. Given all of Jackson’s problems, Democrats weren’t all that eager to re-nominate him for a second term.

(President Henry M. Jackson and First Lady Helen Jackson posing on the boardwalk with two pro-Jackson delegates)

With Jackson vulnerable, two major candidates emerged to challenge him for the nomination. One of them was Alabama Governor George Wallace. An outspoken segregationist, Wallace had positioned himself as the voice for those who were outraged that the President had favored blacks at their expense. As the results of the primaries showed, that outrage wasn’t limited just to the South. Although Wallace only won primaries in the South (three of them to be exact), he performed astonishingly well in the North. In the Wisconsin and Indiana primaries, the Governor got over 30% of the vote. He reached out to ethnic and blue-collar workers who deeply resented that they now had to compete with blacks for jobs, housing, and education. This so-called white backlash against civil rights enabled Wallace to rise above his native region and become a formidable national candidate. He went into Atlantic City certain to dominate Southern delegations and win support from Northern delegates who shared his view that he was fighting the good fight “for the rights of life, liberty, and property.”

While Wallace was challenging the President from the right, South Dakota Senator George McGovern came at him from the left. Although the two men had campaigned together in 1960, they were driven apart by their sharp disagreements over national defense and foreign policy. Alarmed by what he considered to be the President’s dangerously hawkish views, the dovish McGovern had thrown his hat into the ring on September 20th, 1963. He was the candidate of the Dump Jackson Movement, which had been formed by left-wing activists the month before McGovern’s announcement. The DJM sprang up over the belief that Jackson was a reckless President who would carelessly get the country into a nuclear war if he wasn’t stopped in Atlantic City. They saw him as the real-life President Hank Hacksaw, one of Peter Sellers’ characters in the 1963 Cold War satire “Dr. Strangelove” who was persuaded by his unhinged Air Force Chief (played by Sterling Hayden) to launch a nuclear attack against the Soviet Union over an alleged Soviet plot to pollute Americans’ “precious bodily fluids” using water fluoridation. Hacksaw’s wheelchair-bound scientific advisor Dr. Strangelove (also played by Sellers) eventually proved to the President that America’s water supply was indeed safe, making Hacksaw realize he had ordered an unnecessary attack. However, his belated realization came too late to stop the montage of nuclear explosions at the end of the film depicting the resulting nuclear war between the two superpowers. That Hacksaw looked, sounded, and had a name like Jackson’s fed the DJM’s impression that this would be the future unless they prevented Scoop’s re-nomination. Given his well-known opposition, McGovern was recruited to take on the real-life President and stop him from turning film fiction into stark reality. As he put it:

“Somebody has to stop this madness...and I will.”

Nor was the nomination the only source of drama at the convention. Civil rights deeply divided the Democratic Party, and that division was on full display both outside and inside Convention Hall. Outside on the opening day, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. led a peaceful demonstration (shown above) against Wallace’s candidacy. The protestors demanded that the convention soundly reject the segregationist Alabama Governor who proudly stood against everything they believed in. Meanwhile on the convention floor, there was a fight over the seating of the Mississippi delegation. Mississippi, completely ignoring the fact that the country was becoming more integrated, chose to send to the convention an all-white delegation led by the unrepentant white supremacist Senator James Eastland. Instead of being seated right away as expected, Eastland’s delegation found itself being challenged for its’ spot on the floor by an ad hoc mixed-race delegation. Led by civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, this delegation claimed Mississippi’s seats on the grounds that Eastland’s delegation had illegally excluded blacks. Despite the fact that African-Americans now fully enjoyed their right to take part in the country’s political process, Mississippi was continuing to discriminate against them. In light of the VRA, Hamer’s delegation insisted that it should be seated instead of Eastland’s.

Eastland was furious that his official delegation was being challenged by this ad hoc delegation. He defiantly declared:

“No Negro has ever sat in the Mississippi delegation and no Negro ever will!”

He received support in his opposition from Wallace, who publically called for the seating of Eastland’s delegation and for Hamer’s delegation to be dishonorably kicked out. “This convention,” he said privately, “Should not be held hostage by those black jigaboos!”

Scoop, who had spent his Presidency fighting for civil rights, came down on the side of Hamer’s delegation. He believed in forcing the South to change her ways, so he naturally supported the seating of the integrated delegation. McGovern agreed that there should be blacks in Mississippi’s delegation; but instead of seating Hamer’s delegation at the expense of Eastland’s delegation like the President wanted to do, he got behind a liberal proposal to evenly divide Mississippi’s allocated seats between the two delegations. He said it was “the fairest way we can settle this matter.”

Eastland didn’t see it that way. He rejected the compromise out of hand and insisted that only his all-white delegation could be seated since it was the official delegation chosen by his state. Unfortunately for him, he was overruled by unsympathetic liberals who pushed through the convention a resolution mandating that the Mississippi delegation include blacks. The convention then voted to approve a new rule: starting in 1968, no states would be allowed to send segregated delegations to Democratic National Conventions. Refusing to abide by the mandate, Eastland – in full view of television cameras – dramatically walked out of Convention Hall with his delegation in tow. Hamer’s delegation was then seated by default, its’ leader very much pleased by the outcome:

“We came all this way and we got all our seats.”

(Fannie Lou Hamer being interviewed during the convention)

With the Mississippi seating issue settled, the convention turned to the nomination process on Wednesday, August 26th. Speeches were given placing the names of the three major candidates into nomination. The President was nominated first by Texas Senator Ralph Yarborough, one of his most consistent supporters in Congress. Yarborough had voted for all the Fair Deal bills as well as the VRA (a record which gave his Republican opponent George Bush plenty of things to attack him on back home). In his nominating speech, “Smiling Ralph” as he was known praised Jackson as being FDR’s spiritual successor who for three-and-a-half years had been working tirelessly to – as he put it – “put the jam on the lower shelf so the little people can reach it!”

He called Scoop “a great leader of courage” who had stood up for blacks at home and had stood up for America abroad. “We have a President who has shown time and again that he cannot be pushed around. You can just ask Mr. Khrushchev that!”

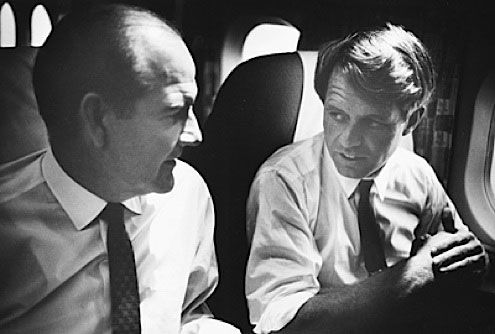

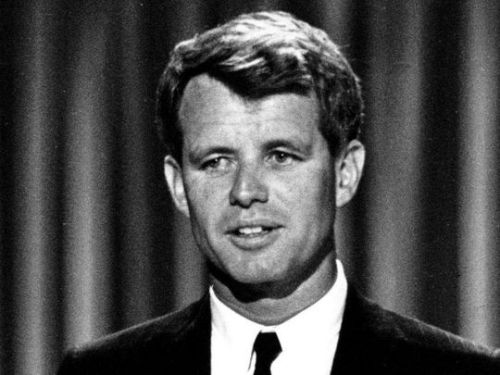

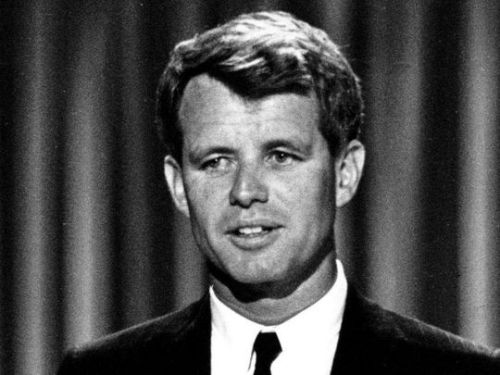

Yarborough lavished the President with praise throughout his speech. Unfortunately for the incumbent, the praise ended with Yarborough. Speaking next for McGovern was Massachusetts Senator Robert F. Kennedy. To say that Bobby Kennedy wasn’t fond of Scoop Jackson is putting it rather mildly. Kennedy, who took slights to his family very seriously, made no secret of the fact that he hated Jackson. That hatred stemmed from the way Scoop had declined to reign in Chief of Naval Operations Hyman Rickover’s contempt of and disrespect for Bobby’s brother Secretary of the Navy John F. Kennedy. Rickover didn’t take JFK seriously, once dismissing him as a “stupid playboy who has only gotten anywhere in life because of his father’s money.”

This treatment, which eventually drove Jack Kennedy to resign and take a job as Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, infuriated the younger Kennedy who swore never to forgive the President. Now in his speech before the delegates, RFK got his revenge by trashing Scoop as a man who had let both the Democratic Party and the country down through his irresponsible leadership. Everyone deserved a better leader, “and that leader, ladies and gentlemen, is a man from the plains who epitomizes the great common sense the people of the Midwest are known for: Senator George McGovern.”

Throughout his speech, Bobby compared the two men and always put McGovern on top as being the better man. His disdain for the lesser man was palpable. Listening to the speech from his spot on the convention floor, Sander Vanocur of NBC News commented that “you can really feel the heat coming off of Senator Kennedy.”

Speaking last for Wallace was South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond. The Dixiecrat candidate for Vice President in 1960, Thurmond represented the angry white segregationist Democrats who were appalled by the actions taken by the Jackson Administration. He claimed that the Party under Jackson “has willfully abandoned states’ rights, one of the proud cornerstones of what it means to be a Democrat.”

With the Party slipping away from its states’ rights roots to be more embracive of civil rights, Thurmond called on all “true” Democrats to rise up behind Wallace and take the Party back. He blamed the racial violence and racial tensions on Scoop, declaring that the only way to restore order in the streets was to make Wallace the next President. Appealing to Northerners who were alarmed by the encroachment of blacks on their turf, Thurmond promised that Wallace as President would roll back the gains made by blacks under Jackson. “Governor Wallace will see to it,” he said amid cheers and boos from the delegates, “That no American should have to compete with a Negro for a job, that no American should have to live next door to a Negro, that no American should have to fear for the safety of their daughters in a school attended by a Negro.”

(Massachusetts Senator Robert F. Kennedy during his McGovern nomination speech)

With the nominating speeches over, the Presidential roll-call vote began. No one was under more pressure going into the first ballot than the President. According to the convention rules, states which held primaries were bounded to support the winner on the first ballot. That meant Scoop could count on the four states he won to vote for him. The bad news though outweighed the good news:

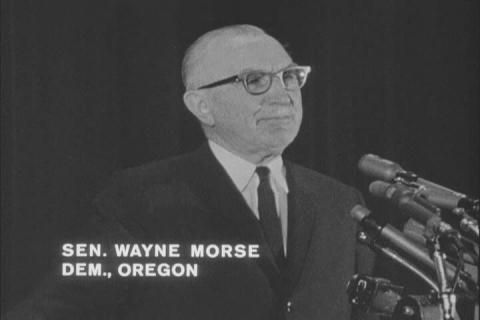

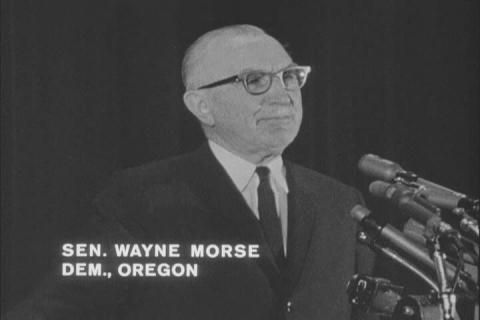

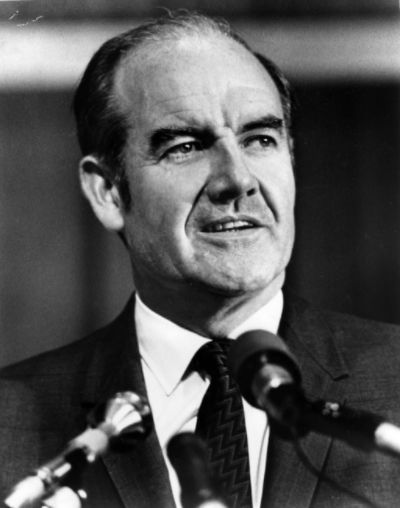

Having been soundly rejected, Scoop released a carefully-worded statement to the press announcing that he accepted the decision of the convention. Nowhere in his statement did he congratulate the new Democratic standard-bearer. The President, feeling the sting of rejection, then left Atlantic City for a few days of quiet seclusion at Camp Ewing in Maryland. With five months left in office, Scoop was now a lame duck President unlikely to do anything more of consequence. As for the man who had replaced him at the top of the Democratic ticket, his first decision following the second ballot victory was choosing his running mate. For McGovern, that was an easy decision to make. Joining him on the ticket would be his first choice: Oregon Senator Wayne Morse. He was picked for two reasons:

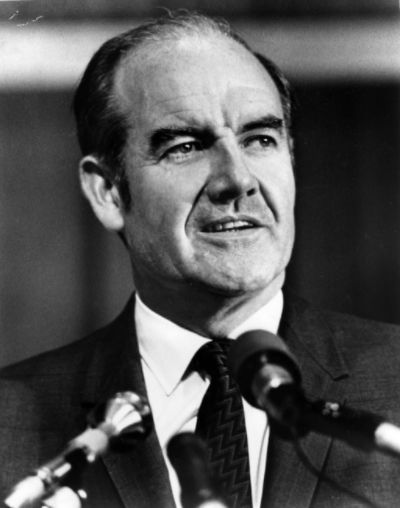

With the nomination of the McGovern-Morse ticket, the convention concluded on Thursday, August 27th with McGovern’s prime time acceptance speech. Scoop, who by this time had taken refuge at Camp Ewing, didn’t watch the speech on television (whether he read the speech afterwards remains unclear). At age 42, McGovern became the first Democratic Presidential nominee to be born after the bloodbath of World War One (Malcolm Forbes was the first on the Republican side). War was very much on the South Dakota Senator’s mind as he walked up to the rostrum to address the convention. After all, it was war which had led to this historic moment. “Tonight,” McGovern humbly began, “I accept your nomination with a full and grateful heart.”

He called his nomination “precious” because “it represents the determination of the people to end the troubles of these last three years and to begin anew. To all those who have lingered on the brink of despair I have this solemn pledge to make: next January I will restore hope to all the people of this land.”

He portrayed himself as the candidate “who listens to the will of ordinary Americans” and painted Forbes as someone “who listens to the will of the privileged few on Wall Street” – a reference to the fact that his campaign’s economic advisor was a well-known and well-connected wealthy Wall Street banker named C. Douglas Dillon. “I am here as your candidate tonight in large part because of a war in Southeast Asia which has been forced upon this nation.”

That was how McGovern brought up the Vietnam War, which was a major theme of his acceptance speech. “I want to end that war. And I make this pledge above all others: that war will be ended.”

The Democratic standard-bearer warned the American people that a vote for Forbes would be a vote to continue Jackson’s “senseless” war which had resulted in “our sons coming home from Vietnam in coffins.”

A vote for McGovern on the other hand would be a vote “for a plan for peace.”

Under his plan which he revealed to the convention audience, he would reach a ceasefire agreement with the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong within three months of his inauguration in January 1965. “By the end of my first 100 days as the President of the United States, every American soldier will be out of the jungle and home in America where they belong. Let us then resolve that never again will we send the precious young blood of this country to die trying to prop up a corrupt military regime abroad.”

Turning to the domestic front, McGovern made the case that ending the Vietnam War promptly “will allow us to focus our attentions on the rebuilding of our own nation, which has been permitted to fall into disarray by those who stand on the status quo.”

With Vietnam no longer the main issue in American life, President McGovern could shift the focus to addressing domestic issues like “schools for our children, the health of our families, the safety of our streets, and the condition of our cities.”

“The highest single domestic priority of the next administration will be to ensure that every American able to work has a job to. That job guarantee will and must depend on a reinvigorated private economy, freed at last from the uncertainties and burdens of war, but it is our firm commitment that whatever employment the private sector does not provide, the Federal Government will either stimulate or provide itself.”

He attacked Republicans for blocking the Medicare bill in 1961 – and Forbes for going along with it – and vowed to fight hard for the establishment of government-run health insurance for the elderly. Once that had finally been achieved, he would then push for the establishment of “a system of national health insurance so that a worker can afford decent healthcare for himself and his family.”

McGovern concluded his acceptance speech:

“So join with me in this campaign. Lend Senator Morse and me your strength and your support, and together we will end war. Together we will end military spending so wasteful that it weakens our nation. Together we will end prejudice based on race and sex. Together we will end the loneliness of the aging poor and the despair of the neglected sick. Together we will move our country forward.”

The next day, convention delegates began to leave Atlantic City for home. With the conventions now over, people began to turn their attentions elsewhere. Across the country that weekend, moviegoers flocked to the theaters to see the new Walt Disney film “Mary Poppins” starring Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke. The lightheartedness of the Disney film, which featured dancing cartoon penguins among other things, provided a timely escape from the drama of the past week. With the Republicans having nominated Forbes and the Democrats having nominated McGovern, people naturally assumed that was it; that the fall campaign would be a fight between these two sides. One man begged to differ. On Monday, August 31st, Governor Wallace issued the announcement to a roomful of reporters that he would be a third party candidate for the Presidency. He would run on the Dixiecrat ticket, with former Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett as his running mate. Barnett was chosen because he was seen in some quarters as a martyr of states’ rights who had been forced by the heavy-handed Federal Government – allegedly at gun point – to desegregate the University of Mississippi in 1962. Traditionally Southern Democrats solidly supported their Party’s Presidential nominee; but in 1964 the old Solid South had collapsed because of civil rights gains. As it was made clear at the convention, Southern Democrats had little appetite to support a Northern liberal like McGovern. This opened the door for Wallace to mount a third party run since he was the South’s overwhelming favorite candidate. Looking ahead to taking on Forbes and McGovern in the fall, he remarked that when it came to civil rights “there’s not a dime’s worth of difference between them.”

Given his championing of segregation and the Southern orientation of the Dixiecrat ticket, it would have been easy to dismiss Wallace as being simply a regional candidate. However, the Alabama Governor couldn’t be dismissed so easily because he had demonstrated appeal outside the South. During the primaries, Wallace cultivated support in the North among blue-collar workers and ethnic voters who opposed having to compete with blacks for jobs, housing, and education. This support manifested itself at the convention when Northern delegates cast their votes for Wallace instead of Jackson or McGovern. Although Wallace came in third place, it was a warning sign to the two major party candidates that he would be a formidable third party candidate. Forbes and McGovern would have to take him seriously, especially in blue-collar states like Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan. With Wallace’s entry into the race, the battle lines had been drawn. It would be Forbes versus McGovern versus Wallace, with the winner becoming the 39th President of the United States.

volksmarschall: I don’t think so.

Except...Jackson’s own party is disunited in taking any action in Southeast Asia. Heck, Scoop is getting more support from the Republicans.

jeeshadow: You’re right. In terms of a political convention melting down, it’s hard to compete with the police beating the crap out of protestors in the streets and the Mayor of Chicago shouting obscenities at Abe Ribicoff.

You’re also right about McGovern and Wallace having a clearer base of support than Scoop does.

As for China being provoked, we will just have to wait and see.

Off the top of my head, Jackson’s predecessor John Sparkman had pushing through Congress a conservation agenda, establishing NASA, starting the national highway system, peacefully resolving the Suez Canal dispute between England and Egypt, and keeping Castro from going completely over to the Soviets as his major accomplishments. Scoop pales in comparison.

El Pip: How do you avenge the Maddox and defeat the Vietcong? The same way you solve all problems: throw plenty of young men at it.

Jackson has had a long-term plan. It’s stabilizing South Vietnam enough militarily that America doesn’t have to worry about her collapsing. He doesn’t want a single united Vietnam. The problem with his plan is that the other side does.

The plan for North Vietnam after US ground troops have invaded is to leave quickly and hope the Chinese don’t notice their presence the way they noticed America’s presence in North Korea during the Korean War.

A plan for the corrupt pit that is the South Vietnamese government? Whoa, whoa, whoa. Slow down there, El Pip. You are asking too much of Jackson.

SirNolan: Pound of flesh? I don’t think I have heard that phrase before.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The 1964 Democratic National Convention

On Monday, August 24th, 1964, all eyes were on Atlantic City, New Jersey as the resort city hosted the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Incorporated in May 1854, Atlantic City was best known for her oceanfront boardwalk, inspiring the board game “Monopoly”, and hosting the annual Miss America Pageant. Now in late August, Democrats gathered at Convention Hall – which could seat 15,000 people – to quadrennially nominate their Presidential ticket. Elected President in 1960, Henry M. Jackson should have been a shoo-in for re-nomination in 1964. After all, no incumbent President had been dumped by his political party after one term in eighty years. Unfortunately for Scoop, he headed into Convention Hall from a position of weakness. He was an unpopular President whose three-and-a-half years in office had been troubled ones. Other than the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1963, Jackson didn’t have much legislative accomplishments to point to. His strong push for civil rights, while earning him praise and admiration from African-Americans, had shattered the Solid South which was the electoral bedrock for the Democratic Party. Liberals were angry at him over his hawkish handling of Vietnam, his eagerness to pour money into defense spending (symbolized by the infamous Dyna-Soar III flop), and his lack of action on negotiating a nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union. Jackson had also been wounded politically by the 1962 steel strike and a huge scandal at the Department of Agriculture which managed to dwarf the Teapot Dome Scandal of the 1920s. Another scandal forced Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to resign from the Administration in early 1964. Given all of Jackson’s problems, Democrats weren’t all that eager to re-nominate him for a second term.

(President Henry M. Jackson and First Lady Helen Jackson posing on the boardwalk with two pro-Jackson delegates)

With Jackson vulnerable, two major candidates emerged to challenge him for the nomination. One of them was Alabama Governor George Wallace. An outspoken segregationist, Wallace had positioned himself as the voice for those who were outraged that the President had favored blacks at their expense. As the results of the primaries showed, that outrage wasn’t limited just to the South. Although Wallace only won primaries in the South (three of them to be exact), he performed astonishingly well in the North. In the Wisconsin and Indiana primaries, the Governor got over 30% of the vote. He reached out to ethnic and blue-collar workers who deeply resented that they now had to compete with blacks for jobs, housing, and education. This so-called white backlash against civil rights enabled Wallace to rise above his native region and become a formidable national candidate. He went into Atlantic City certain to dominate Southern delegations and win support from Northern delegates who shared his view that he was fighting the good fight “for the rights of life, liberty, and property.”

While Wallace was challenging the President from the right, South Dakota Senator George McGovern came at him from the left. Although the two men had campaigned together in 1960, they were driven apart by their sharp disagreements over national defense and foreign policy. Alarmed by what he considered to be the President’s dangerously hawkish views, the dovish McGovern had thrown his hat into the ring on September 20th, 1963. He was the candidate of the Dump Jackson Movement, which had been formed by left-wing activists the month before McGovern’s announcement. The DJM sprang up over the belief that Jackson was a reckless President who would carelessly get the country into a nuclear war if he wasn’t stopped in Atlantic City. They saw him as the real-life President Hank Hacksaw, one of Peter Sellers’ characters in the 1963 Cold War satire “Dr. Strangelove” who was persuaded by his unhinged Air Force Chief (played by Sterling Hayden) to launch a nuclear attack against the Soviet Union over an alleged Soviet plot to pollute Americans’ “precious bodily fluids” using water fluoridation. Hacksaw’s wheelchair-bound scientific advisor Dr. Strangelove (also played by Sellers) eventually proved to the President that America’s water supply was indeed safe, making Hacksaw realize he had ordered an unnecessary attack. However, his belated realization came too late to stop the montage of nuclear explosions at the end of the film depicting the resulting nuclear war between the two superpowers. That Hacksaw looked, sounded, and had a name like Jackson’s fed the DJM’s impression that this would be the future unless they prevented Scoop’s re-nomination. Given his well-known opposition, McGovern was recruited to take on the real-life President and stop him from turning film fiction into stark reality. As he put it:

“Somebody has to stop this madness...and I will.”

Nor was the nomination the only source of drama at the convention. Civil rights deeply divided the Democratic Party, and that division was on full display both outside and inside Convention Hall. Outside on the opening day, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. led a peaceful demonstration (shown above) against Wallace’s candidacy. The protestors demanded that the convention soundly reject the segregationist Alabama Governor who proudly stood against everything they believed in. Meanwhile on the convention floor, there was a fight over the seating of the Mississippi delegation. Mississippi, completely ignoring the fact that the country was becoming more integrated, chose to send to the convention an all-white delegation led by the unrepentant white supremacist Senator James Eastland. Instead of being seated right away as expected, Eastland’s delegation found itself being challenged for its’ spot on the floor by an ad hoc mixed-race delegation. Led by civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, this delegation claimed Mississippi’s seats on the grounds that Eastland’s delegation had illegally excluded blacks. Despite the fact that African-Americans now fully enjoyed their right to take part in the country’s political process, Mississippi was continuing to discriminate against them. In light of the VRA, Hamer’s delegation insisted that it should be seated instead of Eastland’s.

Eastland was furious that his official delegation was being challenged by this ad hoc delegation. He defiantly declared:

“No Negro has ever sat in the Mississippi delegation and no Negro ever will!”

He received support in his opposition from Wallace, who publically called for the seating of Eastland’s delegation and for Hamer’s delegation to be dishonorably kicked out. “This convention,” he said privately, “Should not be held hostage by those black jigaboos!”

Scoop, who had spent his Presidency fighting for civil rights, came down on the side of Hamer’s delegation. He believed in forcing the South to change her ways, so he naturally supported the seating of the integrated delegation. McGovern agreed that there should be blacks in Mississippi’s delegation; but instead of seating Hamer’s delegation at the expense of Eastland’s delegation like the President wanted to do, he got behind a liberal proposal to evenly divide Mississippi’s allocated seats between the two delegations. He said it was “the fairest way we can settle this matter.”

Eastland didn’t see it that way. He rejected the compromise out of hand and insisted that only his all-white delegation could be seated since it was the official delegation chosen by his state. Unfortunately for him, he was overruled by unsympathetic liberals who pushed through the convention a resolution mandating that the Mississippi delegation include blacks. The convention then voted to approve a new rule: starting in 1968, no states would be allowed to send segregated delegations to Democratic National Conventions. Refusing to abide by the mandate, Eastland – in full view of television cameras – dramatically walked out of Convention Hall with his delegation in tow. Hamer’s delegation was then seated by default, its’ leader very much pleased by the outcome:

“We came all this way and we got all our seats.”

(Fannie Lou Hamer being interviewed during the convention)

With the Mississippi seating issue settled, the convention turned to the nomination process on Wednesday, August 26th. Speeches were given placing the names of the three major candidates into nomination. The President was nominated first by Texas Senator Ralph Yarborough, one of his most consistent supporters in Congress. Yarborough had voted for all the Fair Deal bills as well as the VRA (a record which gave his Republican opponent George Bush plenty of things to attack him on back home). In his nominating speech, “Smiling Ralph” as he was known praised Jackson as being FDR’s spiritual successor who for three-and-a-half years had been working tirelessly to – as he put it – “put the jam on the lower shelf so the little people can reach it!”

He called Scoop “a great leader of courage” who had stood up for blacks at home and had stood up for America abroad. “We have a President who has shown time and again that he cannot be pushed around. You can just ask Mr. Khrushchev that!”

Yarborough lavished the President with praise throughout his speech. Unfortunately for the incumbent, the praise ended with Yarborough. Speaking next for McGovern was Massachusetts Senator Robert F. Kennedy. To say that Bobby Kennedy wasn’t fond of Scoop Jackson is putting it rather mildly. Kennedy, who took slights to his family very seriously, made no secret of the fact that he hated Jackson. That hatred stemmed from the way Scoop had declined to reign in Chief of Naval Operations Hyman Rickover’s contempt of and disrespect for Bobby’s brother Secretary of the Navy John F. Kennedy. Rickover didn’t take JFK seriously, once dismissing him as a “stupid playboy who has only gotten anywhere in life because of his father’s money.”

This treatment, which eventually drove Jack Kennedy to resign and take a job as Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, infuriated the younger Kennedy who swore never to forgive the President. Now in his speech before the delegates, RFK got his revenge by trashing Scoop as a man who had let both the Democratic Party and the country down through his irresponsible leadership. Everyone deserved a better leader, “and that leader, ladies and gentlemen, is a man from the plains who epitomizes the great common sense the people of the Midwest are known for: Senator George McGovern.”

Throughout his speech, Bobby compared the two men and always put McGovern on top as being the better man. His disdain for the lesser man was palpable. Listening to the speech from his spot on the convention floor, Sander Vanocur of NBC News commented that “you can really feel the heat coming off of Senator Kennedy.”

Speaking last for Wallace was South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond. The Dixiecrat candidate for Vice President in 1960, Thurmond represented the angry white segregationist Democrats who were appalled by the actions taken by the Jackson Administration. He claimed that the Party under Jackson “has willfully abandoned states’ rights, one of the proud cornerstones of what it means to be a Democrat.”

With the Party slipping away from its states’ rights roots to be more embracive of civil rights, Thurmond called on all “true” Democrats to rise up behind Wallace and take the Party back. He blamed the racial violence and racial tensions on Scoop, declaring that the only way to restore order in the streets was to make Wallace the next President. Appealing to Northerners who were alarmed by the encroachment of blacks on their turf, Thurmond promised that Wallace as President would roll back the gains made by blacks under Jackson. “Governor Wallace will see to it,” he said amid cheers and boos from the delegates, “That no American should have to compete with a Negro for a job, that no American should have to live next door to a Negro, that no American should have to fear for the safety of their daughters in a school attended by a Negro.”

(Massachusetts Senator Robert F. Kennedy during his McGovern nomination speech)

With the nominating speeches over, the Presidential roll-call vote began. No one was under more pressure going into the first ballot than the President. According to the convention rules, states which held primaries were bounded to support the winner on the first ballot. That meant Scoop could count on the four states he won to vote for him. The bad news though outweighed the good news:

- McGovern had won twice the number of primaries

- If the first ballot didn’t end with a winner declared, the states which held primaries would then be released to support whomever they wanted

Having been soundly rejected, Scoop released a carefully-worded statement to the press announcing that he accepted the decision of the convention. Nowhere in his statement did he congratulate the new Democratic standard-bearer. The President, feeling the sting of rejection, then left Atlantic City for a few days of quiet seclusion at Camp Ewing in Maryland. With five months left in office, Scoop was now a lame duck President unlikely to do anything more of consequence. As for the man who had replaced him at the top of the Democratic ticket, his first decision following the second ballot victory was choosing his running mate. For McGovern, that was an easy decision to make. Joining him on the ticket would be his first choice: Oregon Senator Wayne Morse. He was picked for two reasons:

- Morse represented a West Coast state, which would balance the ticket geographically

- Morse had impressed McGovern with his outspoken opposition to the Vietnam War on constitutional grounds. By choosing Morse, McGovern would reinforce his campaign’s anti-war message to sharply contrast the Republican ticket’s support for the war

With the nomination of the McGovern-Morse ticket, the convention concluded on Thursday, August 27th with McGovern’s prime time acceptance speech. Scoop, who by this time had taken refuge at Camp Ewing, didn’t watch the speech on television (whether he read the speech afterwards remains unclear). At age 42, McGovern became the first Democratic Presidential nominee to be born after the bloodbath of World War One (Malcolm Forbes was the first on the Republican side). War was very much on the South Dakota Senator’s mind as he walked up to the rostrum to address the convention. After all, it was war which had led to this historic moment. “Tonight,” McGovern humbly began, “I accept your nomination with a full and grateful heart.”

He called his nomination “precious” because “it represents the determination of the people to end the troubles of these last three years and to begin anew. To all those who have lingered on the brink of despair I have this solemn pledge to make: next January I will restore hope to all the people of this land.”

He portrayed himself as the candidate “who listens to the will of ordinary Americans” and painted Forbes as someone “who listens to the will of the privileged few on Wall Street” – a reference to the fact that his campaign’s economic advisor was a well-known and well-connected wealthy Wall Street banker named C. Douglas Dillon. “I am here as your candidate tonight in large part because of a war in Southeast Asia which has been forced upon this nation.”

That was how McGovern brought up the Vietnam War, which was a major theme of his acceptance speech. “I want to end that war. And I make this pledge above all others: that war will be ended.”

The Democratic standard-bearer warned the American people that a vote for Forbes would be a vote to continue Jackson’s “senseless” war which had resulted in “our sons coming home from Vietnam in coffins.”

A vote for McGovern on the other hand would be a vote “for a plan for peace.”

Under his plan which he revealed to the convention audience, he would reach a ceasefire agreement with the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong within three months of his inauguration in January 1965. “By the end of my first 100 days as the President of the United States, every American soldier will be out of the jungle and home in America where they belong. Let us then resolve that never again will we send the precious young blood of this country to die trying to prop up a corrupt military regime abroad.”

Turning to the domestic front, McGovern made the case that ending the Vietnam War promptly “will allow us to focus our attentions on the rebuilding of our own nation, which has been permitted to fall into disarray by those who stand on the status quo.”

With Vietnam no longer the main issue in American life, President McGovern could shift the focus to addressing domestic issues like “schools for our children, the health of our families, the safety of our streets, and the condition of our cities.”

“The highest single domestic priority of the next administration will be to ensure that every American able to work has a job to. That job guarantee will and must depend on a reinvigorated private economy, freed at last from the uncertainties and burdens of war, but it is our firm commitment that whatever employment the private sector does not provide, the Federal Government will either stimulate or provide itself.”

He attacked Republicans for blocking the Medicare bill in 1961 – and Forbes for going along with it – and vowed to fight hard for the establishment of government-run health insurance for the elderly. Once that had finally been achieved, he would then push for the establishment of “a system of national health insurance so that a worker can afford decent healthcare for himself and his family.”

McGovern concluded his acceptance speech:

“So join with me in this campaign. Lend Senator Morse and me your strength and your support, and together we will end war. Together we will end military spending so wasteful that it weakens our nation. Together we will end prejudice based on race and sex. Together we will end the loneliness of the aging poor and the despair of the neglected sick. Together we will move our country forward.”

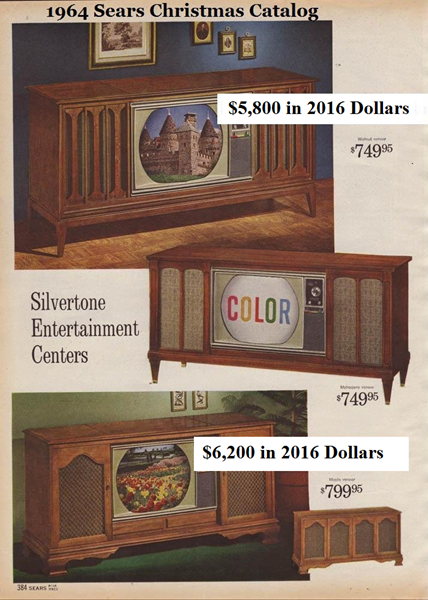

The next day, convention delegates began to leave Atlantic City for home. With the conventions now over, people began to turn their attentions elsewhere. Across the country that weekend, moviegoers flocked to the theaters to see the new Walt Disney film “Mary Poppins” starring Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke. The lightheartedness of the Disney film, which featured dancing cartoon penguins among other things, provided a timely escape from the drama of the past week. With the Republicans having nominated Forbes and the Democrats having nominated McGovern, people naturally assumed that was it; that the fall campaign would be a fight between these two sides. One man begged to differ. On Monday, August 31st, Governor Wallace issued the announcement to a roomful of reporters that he would be a third party candidate for the Presidency. He would run on the Dixiecrat ticket, with former Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett as his running mate. Barnett was chosen because he was seen in some quarters as a martyr of states’ rights who had been forced by the heavy-handed Federal Government – allegedly at gun point – to desegregate the University of Mississippi in 1962. Traditionally Southern Democrats solidly supported their Party’s Presidential nominee; but in 1964 the old Solid South had collapsed because of civil rights gains. As it was made clear at the convention, Southern Democrats had little appetite to support a Northern liberal like McGovern. This opened the door for Wallace to mount a third party run since he was the South’s overwhelming favorite candidate. Looking ahead to taking on Forbes and McGovern in the fall, he remarked that when it came to civil rights “there’s not a dime’s worth of difference between them.”

Given his championing of segregation and the Southern orientation of the Dixiecrat ticket, it would have been easy to dismiss Wallace as being simply a regional candidate. However, the Alabama Governor couldn’t be dismissed so easily because he had demonstrated appeal outside the South. During the primaries, Wallace cultivated support in the North among blue-collar workers and ethnic voters who opposed having to compete with blacks for jobs, housing, and education. This support manifested itself at the convention when Northern delegates cast their votes for Wallace instead of Jackson or McGovern. Although Wallace came in third place, it was a warning sign to the two major party candidates that he would be a formidable third party candidate. Forbes and McGovern would have to take him seriously, especially in blue-collar states like Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan. With Wallace’s entry into the race, the battle lines had been drawn. It would be Forbes versus McGovern versus Wallace, with the winner becoming the 39th President of the United States.

Last edited:

- 1

- 1