11.2 THE WAR OF SEVERUS ALEXANDER AGAINST ARDAXŠIR I. THE CAMPAIGN OF 233 CE.

The autumn and winter months of 232-233 CE were spent planning for the coming campaign and building diplomatic ties. The caravan city of Palmyra was Rome’s long-standing ally, especially since Ardaxšir had captured the port city of Spasinou Charax in Mesene at the head of the Persian Gulf, depriving the city of vital trade routes and cutting its commercial links with India. The ruling family had added

Iulii Aurelii Septimii to their name, reflecting not only their close alliance with Rome, but also with its imperial houses.

Armenia had even more pressing reasons to side with Rome. Its ruling family, who were Arsacids, had made common cause with the Arsacid royal family of Iran to overthrow Ardaxšir. Their aggressive invasion of Sassanid territory resulted in an equivalent invasion of their own lands by Ardaxšir I’s army. A Roman army would march unhindered through their territory, suggesting this had been agreed in negotiations over the preceding months. Herodian refers to:

Armenian archers, some of whom were there as subjects and others under terms of a friendly alliance

that served in the Roman army on the Rhine in 234 CE. They were joined by exiled Parthians, whose influence would be extremely useful in winning over local support in Media.

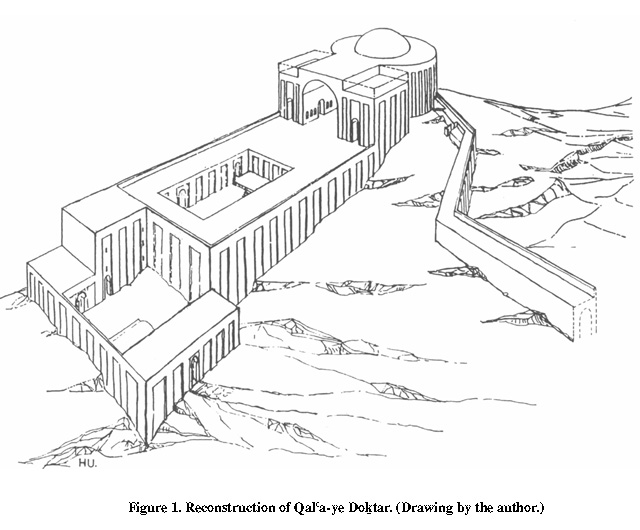

However, the jewel in these diplomatic operations was the addition of the great fortress city of Hatra into Rome’s alliance. Both Trajan and Septimius Severus had attempted to capture the city but failed, situated as it was in the middle of an arid desert and surrounded by imponent double walls 4 miles in length. It lay 60 miles from the Roman frontier that ran along the Jebel Sinjar. This great trading metropolis and religious center controlled the caravan routes through central Mesopotamia to Singara, Zeugma and the Euphrates, but it was now threatened by the rise of the centralizing Sasanian dynasty. Its Arabic ruling house rejected Ardaxšir and looked to its old enemy Rome for help, especially after the Sasanian attempt to capture the city. Severus Alexander looked to integrate Hatra into the Roman defensive system and extend his control from northern to central Mesopotamia, threatening Ctesiphon itself. The emperor needed to secure this position and establish Roman control over this strategically important city.

King Sanatruq II of Hatra.

Apart from raising local troops from these territories, as evidenced by the massive open fort built at Ayn Sinu, the Romans extended their road repair program to Mesopotamia, now free of Sassanid forces. Milestones dated to 232 CE show repairs to communication routes around Singara and the Tigris. Significantly, another repair to the road from Singara to the Khabur river is dated to 233 CE, at the height of the war between Severus Alexander and Ardaxšir. These repairs suggest that the road was a vital communication route, as a significant body of soldiers would have had to be deployed for this construction in the war zone. The road also linked Hatra to Roman territory. The road was clearly reconstructed to facilitate the movement of Roman forces to support their new ally. Some of the statues of Sanatruk II, the last king of Hatra, portray him wearing a breastplate decorated with Hercules, the divine protector of the imperial families. His coins also bear the legend

SC (

Senatus Consulta) surrounded by an eagle with its wings outstretched.

The territory under Sanatruk II’s control stretched over vast areas of land between the Tigris and Euphrates, and appears to have encompassed some areas within the Roman province of Mesopotamia. His alliance with Rome probably granted him a degree of suzerainty over the nomadic Arab communities in these areas rather than control of the cities, towns and forts in the province and along the Euphrates. However, through him, Roman power was now exerted into central Mesopotamia. Diplomacy and a common foe had now attached both Armenia and Hatra to Rome, kingdoms that previous, more illustrious emperors had attempted to subdue but had now been acquired without the loss of a single drop of Roman blood.

The main aim of the campaign of 233 CE appears to have been to add further allies to Rome and feed the fires of revolt against Ardaxšir, strangling the newly born Sasanian dynasty in its cradle (to borrow one of Churchill’s quotes). It was a bold and ambitious plan which, according to Herodian, was drawn up with the advice of the emperor’s council. This council was probably the

concilium principis, formed by the emperor’s most trusted military advisors. Counsel from men with military skill and experience was imperative. The most influential

amicus travelling with the court was Rutilius Crispinus. Another laudatory inscription from Palmyra honoring a leading citizen declares (the underlining is mine):

Statue of Julius Zabdilah, son of Malko, son of Malko, son of Nassum, who was strategos [general] of [Palmyra] at the time of the coming of the divine emperor Alexander, who assisted Rutilius Crispinus, the general in chief, during his stay here, and when he brought his legions here on numerous occasions.

The absence of any reference to Mamaea in these inscriptions or in these discussions is significant. The presence of the

Augusta would have been mentioned by Herodian if she had made any significant contribution to a campaign that would go spectacularly wrong in the end.

For this campaign, the essential source is Herodian, who in his account of the war, quite unusually discards his customary generalizations and describes the campaign in some detail (Herodian, 6.5.1-6.5.2):

After thus setting matters in order, Alexander, considering that the huge army he had assembled was now nearly equal in power and numbers to the barbarians, consulted his advisers and then divided his force into three separate armies. One army he ordered to overrun the land of the Medes after marching north and passing through Armenia, which seemed to favor the Roman cause.

He sent the second army to the eastern sector of the barbarian territory, where, it is said, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers at their confluence empty into very dense marshes [NOTE: Herodian’s geographic descriptions are always a bit garbled]; these are the only rivers whose mouths cannot be clearly determined. The third and most powerful army he kept himself, promising to lead it against the barbarians in the central sector. He thought that in this way he would attack them from different directions when they were unprepared and not anticipating such strategy, and he believed that the Persian horde, constantly split up to face their attackers on several fronts, would be weaker and less unified for battle.

So, Rome’s forces were divided into three separate armies. On its western border, Armenia was accessible by way of the upper Euphrates; from the head-waters of the Euphrates a relatively low pass leads into the valley of the Araxes (modern Arak) which was the heart of Armenia, and this valley also gave good communication with Media Atropatene, (Azerbaijan), and Media proper. The first army, probably beginning its march well before the second and third, headed north towards Armenia, travelling probably along the Amaseia to Melitene road, entering the territory of Rome’s ally from Cappadocia. Herodian gives few clues as to the route taken by the invading army, although the existing topography severely limits the options. Possibly the northern mustering point for Rome and her allies was the Armenian old capital of capital Artaxata (by the III century, the capital had been moved to Valarshapat). The most detailed information we have for a Roman army traversing Armenia is the campaign of Mark Antony in 36 BCE, which we can take as a model. The march to Artaxata was a hard slog across very rough country: Herodian describes it as an almost impossibly difficult crossing. The northern army probably crossed the Euphrates near Melitene (Cappadocia) before ascending into the mountains straddling their path. On the evidence of milestones, it’s also been proposed that it marched along the road linking Zela to Sebastopolis. Road repair is also attested in the environs of Melitene itself.

The Araxes rives (modern Arak).

This was perhaps a mixed force of infantry drawn from the Danubian legions as well as the two Cappadocian legions and a large body of cavalry. If Armenian chronicles are to be trusted, they were joined in Armenia by significant numbers of allied troops; according to Movses Khorenats’i:

There quickly arrived in support great numbers of brave and strong cavalry detachments. Nevertheless Khosrov [NOTE: Tiridates II] took the vast numbers of his army, plus whatever lancers had arrived to support him in the war.

It is likely that Arsacid exiles also joined the invasion force, their target being the Iranian heartland of Media. The staggered start would draw Sasanian forces away from the target areas of the second and third columns. Iulius Palmatus was possibly the commander of this northern army.

There can be little doubt then that this was the route followed by the northern column. The distance from Melitene to Artaxata (located in the Araxes valley) is almost 1,000 km. The mountains were only passable because it was spring, but even at this time of year the climate can be tough, with temperatures exceeding 40 ºC in daytime and approaching freezing at night. If the army covered 24 km/day then it would have taken about six weeks just to reach Artaxata. Even then the marching was only half complete, because the soldiers would have been ordered south to cross another stretch of dry and inhospitable terrain. The target would be Azerbaijan (Media Atropatene, the Sasanian province of Ādurbādagān), and perhaps southwards into Media proper. The army could not of course count on surprise (there were too many spies and informers for that) but the area included important objectives which probably were not strongly defended. The Romans knew that if Ardaxšir sent a strong force to counter the incursion he must simultaneously weaken the south.

Landscape in eastern Turkey near the Iranian border, in the highlands of the ancient Armenian kingdom.

Clearly, it was hoped that the attack on Media through Armenia would result in a Parthian uprising in support of the Arsacid dynasty. As we saw in a previous post, Movses Khorenats’i wrote about the “disobedience” of a part of the Karen clan (which was based at Nehāvand in Media, and also in Khorasan), which is contrasted to the loyalty demonstrated by the Aspahbed and Sūrēn to Ardaxšir. Perhaps Tiridates II and Severus Alexander hoped that the presence of a large force in Media would persuade the Karen to join them. If so, they were to be disappointed, as the Karen appear at the top of the list of court officials under Ardaxšir’s son and successor, Šābuhr.

There may have been a second reason for targeting this province. As we have seen, Ardaxšir had closely associated his rule with the Zoroastrian religion, in particular its religious leaders or

Magi (as the Greeks and Romans called them). The late Roman author Agathias wrote:

This man [Ardaxšir] was bound by the rights of the Magi and a practitioner of secrets. So it was that the tribe of the Magi also grew powerful and lordly as a result of him. It had never been so honored or enjoyed so much freedom … and public affairs are conducted at their wish and instigation.

All Sasanian rulers dated the beginning of their reign in ‘fires’ rather than years, referring to the fire temples founded by each ruler at their accession or coronation; and these “regnal fires” were displayed in the reverse of their coins. It’s possible that one of the objectives of this northern column was the destruction of the sacred fire of Media,

Ādur Gušhnasp. At this time, the old Arsacid capital of Azerbaijan, Phraaspa, was abandoned and moved to Ganzak, near to the place where the great fire temple of Ādur Gušhnasp would be built by the Sasanian kings after 400 CE. A later rock relief at Salmās has been interpreted as showing governors of Ādurbādagān standing before Ardaxšir I and Šābuhr I in acknowledgment of their loyalty. This suggests some sort of acknowledgement that their loyalty may have come under pressure. However, if the fire temple was destroyed at this time by the Romans, and Phraaspa sacked or rebelled, the Roman sources fail to refer to it and Sasanian ones would have little reason to do so.

The Sasanian relief at Salmās in Iranian Azerbaijan.

Meanwhile, the central and southern columns were concentrated at Antioch. Given the staggered nature of the (in hindsight, overly complicated) Roman campaign plan, the southern column would begin moving in second place, and finally the main Roman body, the central column under Severus Alexander himself.

As for the routes available to the southern and central columns, there were several:

- The Euphrates route once taken by Xenophon.

- Alexander’s route, which avoided the desert by skirting the northern fringe of Mesopotamia, crossing the Tigris at Bezabde, and then following the old Achaemenid royal road well to the east of the Tigris through the fertile plains of Arbela and Apolloniatis.

- The Hatra route, the most direct route from Nisibis, which could be varied by crossing the Tigris near Libba and then joining Alexander’s route in its last stages.

The lack of reference to a fleet of any kind indicates that the Roman strategy strove for victory on the plains of Assyria. Surety of supply was essential. Whatever the plan, the Euphrates and Tigris would, by necessity, feature prominently. The Euphrates is an alpine river course as far downstream as Zeugma, where it becomes navigable. Its major tributaries, the Khabur and Balikh Rivers, are dry during summer. The Tigris, like the Euphrates, is alpine in Armenia, and navigable only from Mosul. Unlike its sister river, the Tigris meets tributaries downstream, such as the Great and Lesser Zab, and the Diyala, all of which originate from the Iranian plateau. Thus, given their importance, it is surprising that not one of the ancent sources refers to them in the mechanics of the offensive. Such a silence may not be incidental; Herodian, after all, was aware that Septimius Severus had used a fleet. The Euphrates and Tigris, according to the archetypal Roman invasion of Mesopotamia, should have figured conspicuously in any plans to advance into Babylonia. The silence, especially in Herodian, is significant, according to Bernard Michael O’Hanlon’s analysis of this campaign in his book

The Army of Severus Alexander, AD 222-235, which I will follow from now on.

The Euphrates route was the shortest in mileage and, moreover, offered the prospect of ongoing supply from a river flotilla. Since the Tigris lay further to the east, one was forced to shadow the Jebel Sinjar until the river itself was attained, after which one followed its course downstream into Babylonia and Ctesiphon. This path, while considerably longer, had the advantage of bordering the most bounteous farmland of the region. Even with such forage, supplies would still need to be ferried down the Tigris. Alexander the Great had elected for the Tigris over the Euphrates in his approach to Babylonia. Trajan used both. Dura Europos was the key to the Euphrates march. Singara, legionary base of

Legio I Parthica, exerted a similar importance for the northern route skirting the Jebel Sinjar. Hatra, of course, now stood with Rome. Thus in 232 CE, the Empire controlled all three possible avenues of attack.

The Euphrates near Dura Europos, where it left Roman territory.

The route of the southern column is probably suggested by the creation of the new post of

Dux Ripae at Dura Europos (whose first holder was, according to most scholars,

Gaius Iulius Verus Maximinus, the future emperor Maximinus Thrax); namely, a route downriver into the heart of the Sasanian realm. So, the southern column headed south-east (towards “Babylonia”) along the Euphrates river-valley. Many scholars also accept Herodian’s interpretation of this column as performing an essentially diversionary role, speculating that its objective was not so much to overrun the heartland of the Sasanian Empire but to lay waste the regions around Mēšān/Mesene (the area of territory bounded by both the Tigris and the Euphrates as they approach the Persian Gulf), and Khuzestan/Elymais.

As presented by Herodian, the southern column’s route bears some resemblance to the campaigns of Lucius Verus and Septimius Severus, whereby a Roman army marched into Babylonia with the intention of bringing the enemy into battle, and upon victory, ravaging Ctesiphon. The elaborate nature of Severus Alexander’s plan (according to O’Hanlon), however, meant that the Roman strategy diverged markedly from this template. O’Hanlon suggests that the plan was one that resisted the attraction of the cities of Ctesiphon and Veh-Ardaxšir (founded by Ardaxšir I near Ctesiphon), and so, it did not envisage sending a sizeable force (beyond this column) into central and southern Mesopotamia at the onset of the campaign.

And finally, after leaving Antioch, the central Roman column marched to Zeugma on the Euphrates, and from there to Edessa, Resaina, Nisibis and finally Singara. Evidence for this route can be seen in the reconstruction of the roads running between Singara and Carrhae. The dating of these repairs to the months immediately before the Roman advance is an indication that Ardaxšir left Roman Mesopotamia upon the arrival of Severus Alexander. Also, the string of forts which stretch from Hatra to the eastern Singara-Nisibis road were probably built at the time. (NOTE: contrary to other authors, O’Hanlon believes that Ardaxšir managed to take Nisibis and Carrhae before the arrival of Severus Alexander, only to abandon both cities when the emperor reached Antioch).

According to Herodian (6.5.4-6.5.6), the northern column was the first one to reach its destination:

Alexander therefore devised what he believed to be the best possible plan of action, only to have Fortune defeat his design.

The army sent through Armenia had an agonizing passage over the high, steep mountains of that country. (As it was still summer, however, they were able to complete the crossing.) Then, plunging down into the land of the Medes, the Roman soldiers devastated the countryside, burning many villages and carrying off much loot. Informed of this, the Persian king led his army to the aid of the Medes, but met with little success in his efforts to halt the Roman advance.

This is rough country; while it provided firm footing and easy passage for the infantry, the rugged mountain terrain hampered the movements of the barbarian cavalry and prevented their riding down the Romans or even making contact with them.

O’Hanlon assumes then that this was deliberate. A further assumption is that the Romans were hoping that Ardaxšir’s cavalry army, riding north in response, would be unable to inflict serious damage on this force given the nature of the terrain. As Herodian tells us, this was indeed the outcome. This expedient would have had the effect of concentrating the cream of the Iranian forces in the north, a useful development from Rome’s perspective. O’Hanlon also presumes that the Romans expected that this force would not detain the Sasanian army forever: through intelligence, Ardaxšir would ascertain that a Roman thrust (the southern column, the next to invade), was marching towards his heartland. Accordingly, he would disengage in the north and redirect his efforts (or so the complex Roman plan, as envisaged by O’Hanlon, hoped).

According to Herodian’s retelling of the events, the next Roman force to make itself known to the Sasanian king was the southern column (Herodian, 6.5.6-6.5.7):

Then men came and reported to the Persian king that another Roman army had appeared in eastern Parthia [NOTE: meaning southern Mesopotamia and Khuzestan, geography was not Herodian’s strong point] and was overrunning the plains there.

Fearing that the Romans, after ravaging Parthia unopposed, might advance into Persia, Artaxerxes left behind a force which he thought strong enough to defend Media, and hurried with his entire army into the eastern sector. The Romans were advancing much too carelessly because they had met no opposition and, in addition, they believed that Alexander and his army, the largest and most formidable of the three, had already attacked the barbarians in the central sector. They thought, too, that their own advance would be easier and less hazardous when the barbarians were constantly being drawn off elsewhere to meet the threat of the emperor's army.

This passage implies that the southern force was not expecting to engage in extensive hostilities during its march; the developments in Media and Assyria would draw off the greater portion of the Persian strength. What reasons, then, can we construe for its formation? Given the staggered nature of the offensive, it could be argued the Romans were hoping that the news of its advance would compel Ardaxšir to disengage in the north. In his haste to return south lay the Roman hope of a decisive victory.

And now, the whole key to the Roman plan (as envisaged by O’Hanlon): meanwhile the main Roman column, having invaded by the central route (having marched across the northern Mesopotamian plains to Singara), would attempt to intercept and annihilate Ardaxšir’s army as it raced southwards. The effort expended on the roads leading to Singara in the precious hours of the invasion’s eve is critical; there’s also Herodian’s information that the main weight of the Roman invasion was assigned to the central army group. If Severus Alexander hoped for victory, his hope lay in the strength of this main column being brought to bear.

The Jebel Sinjar, which together with the Khabur river marked the border of Roman Mesopotamia.

It might also be suggested that the Romans created the southern army group to attempt a hit-and-run raid on Ctesiphon via the Euphrates river-valley. This was not beyond the capacity of a small cavalry force, especially in the absence of substantial resistance. If Ardaxšir’s main army group was not overwhelmed by the might of the central army group, the destruction of Ctesiphon and/or Veh-Ardaxšir would still serve Roman ends. Probably, if Severus Alexander’s strategy had succeeded, the central army column could have marched down the Tigris river valley to join them in Babylonia after defeating Ardaxšir in Assyria (northern Mesopotamia), akin to what a decade later Timesitheus would do at Resaina, thus sealing the fate of Ardaxšir’s cities.

The plan failed in a most evident way. According to Herodian (6.5.8-6.5.9):

All three Roman armies had been ordered to invade the enemy's territory, and a final rendezvous had been selected to which they were to bring their booty and prisoners. But Alexander failed them: he did not bring his army or come himself into barbarian territory, either because he was afraid to risk his life for the Roman empire or because his mother's feminine fears or excessive mother love restrained him.

She blocked his efforts at courage by persuading him that he should let others risk their lives for him, but that he should not personally fight in battle. It was this reluctance of his which led to the destruction of the advancing Roman army.

Of course, for Herodian it was all Mamaea’s fault (even if there’s no proof that she followed her son beyond Antioch), so that his admired Severus Alexander could remain blameless. The result: the southern column, which was advancing “carelessly”, met a bloody defeat at the hands of the Sasanian army (Herodian 6.5.9-6.5.10):

The king attacked it unexpectedly with his entire force and trapped the Romans like fish in a net; firing their arrows from all sides at the encircled soldiers, the Persians massacred the whole army. The outnumbered Romans were unable to stem the attack of the Persian horde; they used their shields to protect those parts of their bodies exposed to the Persian arrows.

Content merely to protect themselves, they offered no resistance. As a result, all the Romans were driven into one spot, where they made a wall of their shields and fought like an army under siege. Hit and wounded from every side, they held out bravely as long as they could, but in the end all were killed. The Romans suffered a staggering disaster; it is not easy to recall another like it, one in which a great army was destroyed, an army inferior in strength and determination to none of the armies of old. The successful outcome of these important events encouraged the Persian king to anticipate better things in the future.

Herodian’s account is probably an exaggeration.

Cohors XX Palmyrenorum, based at Dura and which with almost total certainty marched with this army group survived after the campaign, even if reduced to 50% of its force. What the southern Roman column suffered was a clear defeat with many casualties, but it was able to retreat. Plus, the description of the battle by Herodian is clearly borrowed from Plutarch’s depiction of Carrhae.

To make matters worse, an epidemy seems to have been partially responsible for paralyzing the Roman central column (Herodian, 6.6.1-6.6.2):

When the disaster was reported to Alexander, who was seriously ill either from despondency or the unfamiliar air, he fell into despair. The rest of the army angrily denounced the emperor because the invading army had been destroyed as a result of his failure to carry out the plans faithfully agreed upon.

And now Alexander refused to endure his indisposition and the stifling air any longer. The entire army was sick and the troops from Illyricum especially were seriously ill and dying, being accustomed to moist, cool air and to more food than they were being issued. Eager to set out for Antioch, Alexander ordered the army in Media to proceed to that city.

And then the northern column had to endure the ordeal of a retreat through the now snowed and desolate northern Zagros and the highlands of Armenia, suffering grievously in the process (Herodian, 6.6.3):

This army, in its advance, was almost totally destroyed in the mountains [of Armenia]; a great many soldiers suffered mutilation in the frigid country, and only a handful of the large number of troops who started the march managed to reach Antioch. The emperor led his own large force to that city, and many of them perished too; so the affair brought the greatest discontent to the army and the greatest dishonor to Alexander, who was betrayed by bad luck and bad judgment. Of the three armies into which he had divided his total force, the greater part was lost by various misfortunes - disease, war, and cold.

With the benefit of hindsight, several things can be said about the Roman invasion plan (always according to O’Hanlon’s hypothesis, which as far as I know is the only serious attempt at reconstructing the whole campaign):

- First, it was a plan far too complicated for its time. It involved taking a huge risk, dispersing the Roman forces on a 1,300 km front from the Araxes river valley to the Gulf Coast, at a time when command and control techniques were almost non-existent. Even during IIWW achieving full coordination in so wide a theater with so widely dispersed army groups would’ve been an achievement.

- The main objective of the campaign was sound: bring the Sasanian army to a pitched battle and then destroy it. And only then, advance into southern Mesopotamia, without risking harassing and further surprises on the way (in the IV century, Julian went straight for Ctesiphon and suffered the consequences). The problem though was always the same: how to bring a highly mobile enemy, much more mobile than the Roman army, to a pitched battle in a place chosen by the Romans.

- The plan’s second and perhaps gravest fault though was that it disregarded completely the strengths of the enemy. By 232 CE, Ardaxšir was an old fox, who’d been constantly at war for almost two decades. And who had showed himself a masterful commander and strategist on repeated occasions, much better of course than Severus Alexander (who’d never commanded an army in his life) and probably most of Severus Alexander’s military councilors. Thus, it’s very probable that despite Herodian’s words, Ardaxšir never fell for the Roman plan: he abandoned completely northern Mesopotamia/Assyria, only retained a token force in Media and his main army never left central/southern Mesopotamia, guarding the approaches to Ctesiphon and Pars, and keeping his options and retreat avenues open. In this sense, it’s probable that the Roman plan was going to fail from the start.

- Even if Ardaxšir had bitten the bait, it was very optimistic for the Romans to think that they would be able to intercept in the plains of northern Mesopotamia Ardaxšir’s cavalry army, which was much more mobile than the Roman one.

- The Roman plan as reconstructed by O’Hanlon smells strongly of a plan devised by a clever, cultivated young man who’d read a lot of books about war and history but who’s never experienced the real thing himself (a perfect description for Severus Alexander), mixed with the strategic and military hindsight given by more experienced men (the ones who were part of his concilium, and perhaps field commanders like Cn. Iulius Verus Maximinus). In my opinion, this makes it credible, because probably Severus Alexander, who was in his late twenties by now and wanted to dispel the doubts about his military abilities at once, devised his own plan and imposed it over the army. But for example he did never stop to consider if gathering a force of several thousand men in the middle of the Mesopotamian desert in summer and keeping them static in one point was a safe course of action. That an epidemic would hit the army in such conditions was highly probable, as a seasoned commander would’ve probably known (the same had happened to the armies of Trajan and Septimius Severus when besieging nearby Hatra in similar conditions).

But it backfired spectacularly. Severus Alexander emerged from the campaign utterly discredited amongst the army. While Ardaxšir could now boast of being the first Iranian king in more than a century to have suffered a full-scale Roman offensive without being defeated and having preserved Ctesiphon.

Eastern Anatolian highlands in winter.

On the positive side for the Romans, Herodian writes (Herodian 6.6.4-6.6.6):

In Antioch, Alexander was quickly revived by the cool air and good water of that city after the acrid drought in Mesopotamia, and the soldiers too recovered there. The emperor tried to console them for their sufferings by a lavish distribution of money, in the belief that this was the only way he could regain their good will. He assembled an army and prepared to march against the Persians again if they should give trouble and not remain quiet.

But it was reported that Artaxerxes had disbanded his army and sent each soldier back to his own country. Though the barbarians seemed to have conquered because of their superior strength, they were exhausted by the numerous skirmishes in Media and by the battle in Parthia, where they lost many killed and many wounded. The Romans were not defeated because they were cowards; indeed, they did the enemy much damage and lost only because they were outnumbered.

Since the total number of troops which fell on both sides was virtually identical, the surviving barbarians appeared to have won, but by superior numbers, not by superior power. It is no little proof of how much the barbarians suffered that for three or four years after this they remained quiet and did not take up arms. All this the emperor learned while he was at Antioch. Relieved of anxiety about the war, he grew more cheerful and less apprehensive and devoted himself to enjoying the pleasures which the city offered.

So, in Herodian’s view the “barbarians” had also suffered grave losses, which kept the border safe for some years. This is a view accepted by many historians (including O’Hanlon, to a certain degree). That the campaign was not an absolute disaster is proved by Herodian’s assertion that Severus Alexander was planning for a new offensive for the oncoming campaign season in 234 CE, and that the Roman army was able to retreat without having to pay tribute or ransom and without making territorial concessions (something that neither Macrinus nor Philip the Arab were able to do). But on the other side, we should remember that, as we saw in previous posts, by 233/234 CE, Ardaxšir was minting coins at Marv and turning several Central Asian small states and the once mighty Kushan empire into Sasanian tributaries, which is hardly the sign of a defeat. And the territorial security of Rome's eastern provinces would not last for long.

In Antioch, Severus Alexander received alarming news from Europe: taking advantage of the weakening of the European border garrisons, the Alamanni had broken the limes in Upper Germany and Raetia, and even Italy could be in danger. The emperor was urgently recalled by the governors of the invaded provinces, and he had to leave the East in a hurry in the spring of 234 CE, taking with him the

vexillationes of the western legions, which were now seething with hatred and resentment against him: their homes were now endangered while they’d fought a pointless war that they did not even want to join to begin with. When the emperor tried to buy peace with the Alamanni, the legionaries of

Legio I Minervia proclaimed the popular commander Cn. Iulius Verus Maximinus as Augustus. Other forces joined them, including the Praetorians and

Legio II Parthica, and Severus Alexander, his mother and all of his secretaries and ministers were lynched at the legionary fortress of Mogontiacum in Upper Germany on 19 March 235 CE.

Denarius of Cn. Iulius Verus Maximinus (AKA "Maximinus Thrax) as Augustus. On the reverse, the by now familiar legend FIDES MILITVM.

EDIT: I'll add some more comments about the campaign, and about Severus Alexander`s (hypothetical) plan. This is a map of northern Mesopotamia in Roman times:

The Roman border followed the southern slopes of the Jebel Sinjar (the mountains in the center of the map), and to the west of the Jebel Sinjar it followed the Khabur river until it met the Euphrates near Circesium. The main Roman army was located either at Nisibis or Hatra, south of the Jebel Sinjar. This is an expanse of utter waterless desert, where temperatures in summer can hit 50ºC regularly. Hatra is located 50 km from the Tigris, and Singara 80 km from the Tigris. The distance between Singara and Hatra was 110 km. This was the area where (according to O'Hanlon) the decisive battle had to take place.

In 344 CE. the Roman emperor Constantius II managed to do something similar to what Severus Alexander had probably envisaged. The Sasanian king Šābuhr II wanted to attack the Roman fortress of Singara; he'd aproached it along the eastern bank of the Tigris (logical, as it had fertile farmland, while the western bank was a barren desert and open to Roman attacks). When he was opposite Singara, the large Sasanian army crossed the Tigris on a pontoon bridge, and then suddenly the Roman field army of the East, led by emperor Constantius II, appeared. It was a total surprise for Šābuhr II (and an obvious failing of his scouts), and now his army was trapped with its back to the river, on a narrow plain surrounded by hills, and with only a narrow pontoon bridge at his back for escape route. It was precisely the type of battlefield situation where the Sasanian superiority in cavalry (and its superior mobility) could not be brought to bear, as the battle was to be a frontal encounter without possibility of flanking maneuvers; exactly the kind of battle that favoured the Roman heavy infantry.

But in my opinion it's quite a stretch of the imagination that, of all the places where Ardaxšir I could cross the Tigris he would do so in this part of the river, in Roman controlled territory (as Hatra was a Roman ally) and without sending scouts first; on top of that, had he succeeded then he would've needed to cross a large expanse of open desert with a large army to reach southern Mesopotamia, when he could have done that approach march much more safely along the eastern bank of the Tigris. In 344 CE, Šābuhr II crossed the Tigris there precisely because his objective was Singara, but in 233 CE there was no guarantee at all that Ardaxšir I would've done the same, and I think that it would've been quite illogical of him to do so.

(I am not going to look it up on wiki before you post the conclusion to the war

(I am not going to look it up on wiki before you post the conclusion to the war  )

)