8.1 THE REVOLT OF ARDAXŠIR I. THE OBSCURE ORIGINS OF THE HOUSE OF SĀSĀN IN PĀRS.

Modern scholars mostly agree that the Sasanians were newcomers in Pārs, and not members of the traditional nobility of the area; most probably they were even completely unrelated to the royal family of Pārs. Graeco-Roman sources are practically useless to reconstruct the rise of the Sasanians in this province, and so the only ancient sources left are Middle Persian ones, Islamic ones (above all, Tabarī and Ferdowsī) and Armenian ones (especially Agathangelos and Movses Khorenats’i). These are the sources mostly used by modern scholars.

In this post, I will use mainly one paper by a modern scholar:

Working with Perso-Islamic sources is difficult because the conception of writing history in these eastern cultures was different from the one prevalent in the Graeco-Roman world. The renowned American Iranologist R.N.Frye notice time ago how, in these histories, facts and people are always made to fit into preexisting patterns, usually of religious or cultural origin. For example, Darius I was helped by seven Persian families to overthrow the “false king” Gaumata, Aršak I entered the Iranian plateau with a following of seven clans, and there were supposedly seven great “Parthian” clans during the Sasanian era.

The origins of the Sasanian family are surrounded in mystery, as there are scarcely two ancient sources, eastern of western that agree between them. Graeco-Roman and Armenia sources are markedly hostile to the Sasanians for historical reasons and seem to compete between them to give Ardaxšir I the humblest origins possible:

Meanwhile, Tabarī and Ferdowsī both stated that Ardaxšir I came from aristocratic origins, from among the nobility of Pārs. Most scholars tend to take Tabarī’s account as authentic or more acceptable; in it Pābag was the son of Sāsān, while the VI century Middle Persian book Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšīr ī Pābagān, like Ferdowsī’s Šāhnāme both stated that Pābag’s daughter married Sāsān. And the Zoroastrian “sacred encyclopedia, the Bundahišn, gives another genealogy:

The royal inscriptions of Ardaxšir I state that Pābag was his father, and Sāsān their “ancestor”, but without implying that Sāsān was Pābag’s father. And the inscriptions of Šābuhr I follow the same scheme; plus in both cases Sāsān is not called “king”, but merely “lord”, while Pābag is called “king”. Then, why did the family call themselves “Sasanians”, if Sāsān was such an obscure character? If that was not enough, Sāsān is a very rare name in western and central Iran. Before Ardaxšir I, it’s completely unattested in Pārs, Media and Parthia and it only appears in “eastern Iran”, the large land area inhabited or ruled by Iranian peoples east of the Arsacid empire proper: Soghdiana, Bactria, Sakastan, etc.

Ardaxšīr of course claimed Sāsān as the patriarch of the dynasty. An ostraca was found in Central Asia by Soviet archaeologists in the late 1980s which contained the epigraphic form ssn designating Sāsān as a deity. But because of its absence in the Avesta and the Old Persian documents, it is difficult to know how it was related to the Zoroastrian religion. Recent scholarly research seems to show that the deity represents Sesen, an old Semitic god which is found in Ugarit as early as the second millennium BCE. Be that as it may, in the first century CE coins can be found in Taxila in Gandhara with the name Sasa, which may be connected to Sāsān because the emblem on the coin matches the "coat-of-arms" for Šābuhr I.

Tabarī mentions the mysterious Sāsān as the ruler and custodian of the Anāhīd fire-temple at Istakhr, while his son Pābag became later king of Istakhr. This seems to be in accordance with the ŠKZ inscription, and so it represents the “official” position. Early Islamic sources based on Sasanian tradition emphasize the religiosity of Sāsān and his devotion and even mention him as an ascetic. In fact, Sāsān’s lineage is said to originate in India, the bastion of asceticism (according to Bal’ami). Only in this way could Ardaxšīr claim to have both priestly and royal lineage, meaning the story of Pābag as the king of Istakhr marrying the daughter of the priest (Sāsān) of the most important fire-temple at Istakhr. It is in this manner that Ardaxšīr could manufacture the double (king-priest) lineage topos which is such an important part of Sasanian religious and political tradition. And it’s not surprising that in the priestly tradition the religious origin of Ardaxšīr is emphasized, becoming connected with royalty, while the epic / royal tradition such as the Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšīr ī Pābagān emphasizes the royal origin and then its connection with the religious tradition of Ardaxšīr.

Aerial photograph of the remains of Istakhr.

Some iconographical features of Pābag’s coinage and imagery have provided scholars with some clues, which could help to shed some light into this mess. On the earliest coinage of Pābag with his elder son, Šābuhr, his headgear is unlike any of the Arsacid or Persis kings. It is only Šābuhr who presents himself on the obverse wearing the headgear (the bejeweled kolah / kulaf) symbolizing kingship or political power. The royal narrative informs us that Pābag dethroned the king of Istakhr, Gozīhr (according to the East Roman historian Agathias, whose informant Sergius apparently had access to the royal Sasanian archives). Pābag however, had designated his elder son, Šābuhr, and coins were struck showing the two on either side. Ardaxšīr did not accept this and removed his brother and those who stood before him and subsequently had coins minted in the image of his father and himself. But in the joint coinage of Ardaxšīr-Pābag, the father bears the kingly crown of Persis.

Silver drachm with Šābuhr (wearing the bejewelled kolah of Persian kings) in the obverse and his father Pābag in the reverse, wearing what scholars believe to be some kind of priestly headgear.

Silver drachm with Ardaxšīr in the obverse and his father Pābag in the reverse, wearing this time the royal kolah.

Drawing of a graffito from Persopolis assumed by scholars to represent Pābag.

In several extant sources sources Pābag is said to have been the priest of the fire-temple of Anāhīd at the city of Istakhr and this must have been a stage for the rallying of the local Persian warriors who were devoted to the cult of this. Pābag’s priestly function can also be seen in an extant graffito from Persepolis. Or could it be that the inability of the Persian royalty in the face of Arsacid power caused a priest-king to take the lead and revolt? This is a difficult question to answer, but it would not be the only time in the history of Iran that a holy man or religious leader rose up and attempted the conquest of the Iranian Plateau. Sāsān and Pābag were the priests / caretakers of the Anāhīd fire-temple at Istakhr and so Pābag’s function in relation to the fire-temple may have given backing to Ardaxšīr’s claim to rulership after the initial civil wars.

Anāhīd is important, since she was an object of devotion for heroes, warriors and kings in the Zoroastrian sacred text, the Avesta (for example in Yašt V, Ābān Yašt). During the Achaemenid period, in the beginning of the fifth century BCE, Artaxerxes II also worshipped Anāhīd (Anahita) along with Mīhr (Mithra) and Ohrmazd (Ahurā Mazdā). Thus, her cult must have been an old one in Persis and the temple may have been a location where the Persian tradition was kept alive. Her warlike character was the symbiosis of ancient Near Eastern (Ištar), Hellenic (Athena) and Iranian traditions which was used to legitimate kingship in the Sasanian period.

The goddess Anāhīd in a Sasanian silver jar.

Scholars may never know who Sāsān really was but his dual function of priest-king of Persepolis-Istakhr seems to be a well-established tradition. Daryaee suggests that if Pābag was anyone of rank, he was a local ruler at best, taking Tabarī’s assertion that he ruled a small area by the salt lake of Bakhtagān to the south of Istakhr the south called Khīr. And it's Pābag who first aspired to rule in Istakhr and took it over with his elder son Šābuhr, and not by the order of Ardaxšīr as Tabarī wrote. To Daryaee, this is made clear by Pābag’s coins with his elder son, Šābuhr.

Lake Bakhtagān.

Daryaee also notices Pābag’s name as an important pointer to his religious function as Pābag is a hypocrastic from Pāb, which means “father” in Middle Persian. Furthermore, Ardaxšīr at the time may have been in the south at Dārābgird far away from the Pābag-Šābuhr takeover of Istakhr. Daryaee suggests Ardaxšīr was an usurper in his own family who upon seeing his father taking charge of Istakhr and nominating his elder son and the brother of Ardaxšīr, began his campaign initially not against the Arsacid king Ardawān, but against his own father and then brother.

Daryaee points out that the German scholar Michael Alram suggested that Šābuhr and Ardaxšīr could have been portraying the dead image of Pābag on their early coinage. If so, then Ardaxšīr was only rebelling against his own brother. This could also explain why Ardawān did not send troops at first to meddle in the family feud. Again, these are only mere speculations and show that Ardaxšīr probably did not have a strong claim to any throne and was not in line for rulership.

When Ardaxšīr finally became the sole ruler of Iran, he constructed an elaborate genealogy which is captured in the late book Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšīr ī Pābagān:

When looking at this line, Daryaee notices that every possible connection to divinity, royalty and nobility was being exploited by Ardaxšīr, which to him likely suggests that he was heir to none of them! The Kayānid dynasty in the Avesta, the mysterious protective deity Sāsān, and the connection to Dārāy (probably the conflation of the Achaemenids, Darius I and Darius III, and the kings of Pārs, Dārāyān I and Dārāyān II) all suggest to him that the first Sasanian king falsified his lineage. Ardaxšīr’s falsified connections, however, would have given him the prestige of being the first human to be shown receiving the diadem of rulership from Ohrmazd, something that was never shown in Achaemenid reliefs. A noble Persian would not have needed to be shown receiving the diadem from Ohrmazd; only an upstart would be in need to make the claim of being from the race of the yazdān. Looking at the early Sasanian rock reliefs, they show the king and the gods as having similar physical features, size, clothes, horses and harnesses. In terms of proportion, the Sasanian king is an exact mirror image of the yazatas / yazdān.

Perhaps it’s because of this “sacrilege” that some Zoroastrian texts like the Dēnkard and the Nāme-ye Tansar (Letter of Tansar) questioned Ardaxšīr’s legitimacy and his attempt at changing the tradition.

Perso-Arabic sources state that Ardaxšīr was the argbed (castellan) of Dārābgird in eastern Pārs when he began his campaign. However, the earliest physical evidence for Ardaxšīr can be found at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah (literally meaning “the Glory of Ardaxšir”, a city founded by him, near modern city of Fērōz-ābād, also known in late Sasanian and early Islamic times known as Gōr), on the southern fringes of Pārs. Daryaee thinks that it is from here, far from Khīr, the stronghold of Pābag, and Istakhr, the stronghold of the kings of Pārs, and still further away from the king of kings, Ardawān, that Ardaxšīr began his campaign. Daryaee thinks that Ardaxšīr moved from the remote Dārābgird to Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah which was behind the mountains and still defensible, but closer to the center of power in Persis, Istakhr, when Pābag’s revolt took place against the king of Pārs at Istakhr. However mountainous the road from Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah to Istakhr is, it’s still an easier route to traverse than from Dārābgird to Istakhr.

Remains of Dārābgird.

Remains of Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah, the city founded by Ardaxšīr I. Notice how both it and Dārābgird are built following a circular plan.

Superimposed sketch of the main streets, gates and roads of Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah.

Ardaxšīr’s beginnings may be connected to his first rock-relief which shows him receiving the diadem of rulership from Ohrmazd in front of his retinue at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah. Based on the date supplied by Šābuhr I’s inscription at Hajjīābād, Daryaee agrees with the German scholar Josef Wiesehöfer that the year 205/206 CE (which Šābuhr I chose as the beginning of the Sasanian era) does not mark the date of Ardaxšīr’s uprising but rather Pābag’s rebellion and movement from Khīr to Istakhr. This date coincides with the rule of the Arsacid king Walāxš V (192–207 CE) and the wars with the Roman emperor Septimius Severus.

As we have seen in previous posts, the Arsacids were not only involved in a bitter war with the Romans, but also with dynastic squabbles and provincial revolts. Septimius Severus, first in 196 CE, and then again in 198 CE invaded the Arsacid realm and was able to sack Ctesiphon. At the same time, we hear of the revolt by the Medes and the Persians against the Arsacid king in the Syriac Chronicle of Arbela which caused internal problems. The kings of Pārs could not rely on their Arsacid overlords anymore to support them in the face of local uprisings, such as that of Pābag.

Daryaee is reluctant to accept the “official” version of history where according to Tabarī, Ardaxšīr was the argbed of Dārābgerd at this time and told his father Pābag to revolt against the Arsacids in 211/212 CE. To him, it’s more probable that between 205/206 and 211/212 CE Pābag had taken the throne at Istakhr and then chosen his eldest son Šābuhr as the heir. Ardaxšīr as an act of rebellion would then have moved from Dārābgerd to Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah and built himself a fortification from where he could launch his attack against his elder brother when Pābag died.

Ardaxšir’s first investiture rock-relief at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah.

Ardaxšir’s rock-relief at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah would then have been the symbol of his rebellion against his father, or more probably against his brother. Pābag must have died sometime before 211/212 and so by this date both Ardaxšīr and Šābuhr minted coins with the title of “king,” with the image of their recently deceased father on their coins. Daryaee also cites the important notice in the Zainu’l-Akhbar (a chronicle written in the XI century at the Ghaznavid court by Abū Sa’id al-Dahhāk) which to him seems to corroborate the thesis that Ardaxšīr indeed proclaimed himself king in 211/212 CE. According to the Zainu’l-Akhbar, when Ardaxšīr began his conquest Ardawān came to face him. What´s noteworthy to Daryaee is that the text states:

This clearly places Ardaxšīr’s claim to kingship and local investiture (at Istakhr or Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah) in 211/212 CE. The event of 211/212 CE which is the defeat and death of his elder brother Šābuhr also most probably coincided with his coronation relief at Naqš-e Rajab and the coinage that Ardaxšīr minted without his father’s image.

Ardaxšīr's "second" investiture relief, at Naqš-e Rajab near Istakhr.

Between 211/212 CE and the defeat of the Arsacid ruler Ardawān in 224 CE Ardaxšīr consolidated his power in the province of Pārs and the adjoining regions. In 216/217 CE he would certainly begin his propaganda campaign against the Arsacids as their prestige had been marred by the Roman actions at the Arsacid family sanctuary. How could a dynasty who was not even able to protect their own family be able to defend the Iranians? The kings of Pārs had been defeated by 211/212 and others a bit later as they may have been involved in aiding the Arsacid king of kings at Nisibis and therefore would have been ill prepared to fight the upstart. Ardaxšīr might have felt that a new house had to wrest away control of the royal throne, as the old one (the Arsacids) had been soundly humiliated. Daryaee also adds that apparently other brothers of Ardaxšīr were also worrisome to him and he had them killed at this time. Once he had the province of Persis and the adjoining regions under control he began to call himself “King of Iranians,” (šāh ī ērān) in his coinage.

Gold coin of Ardaxšīr I as “King of Iranians,” (šāh ī ērān).

Thus, he still refrained himself from taking the title of “King of Kings”, which would’ve been an open defy to Ardawān V. The šāh ī ērān title would probably refer to his conquest of Pārs and the wresting of Istakhr from the hands of the local rulers and those in his family who contended for his rule over it. According to Daryaee, it’s then that he had his rock-relief at Naqš-e Rajab, close to Istakhr, carved. Thus, one may surmise that the Naqš-e Rajab relief represents his victory over the kings of Pārs and the control of Istakhr as the center. The investiture scene is at the center of this event. That may well be the reason that Ardawān is still not under the hoof of Ardaxšīr’s horse on this relief, as he is at the Naqš-e Rustam relief. The importance of the local kings also made Ardaxšīr mindful to respect them as seen in the iconographical remains of this period. He also co-opted them into his genealogy and adopted their characteristic dress and headgear, thus representing himself as the continuer of the old Persian tradition existing at Istakhr.

Having consolidated his power in Pārs and having subdued the kadagxwadāyān “petty-lords”, he conquered adjoining regions which would have alarmed Ardawān. Then the fateful battle of Hormozdgan in 224 CE brought the defeat and death of Ardawān and brought about a new phase of Ardaxšīr’s rule. The Battle of Hormozdgan was carved in the location where he rose up in Pārs, at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah. By then he could claim to be the “King of Kings of the Iranians”, and he reflected this in his coinage.

Silver drachm of Ardaxšīr I as King of Kings of Iran.

Modern scholars mostly agree that the Sasanians were newcomers in Pārs, and not members of the traditional nobility of the area; most probably they were even completely unrelated to the royal family of Pārs. Graeco-Roman sources are practically useless to reconstruct the rise of the Sasanians in this province, and so the only ancient sources left are Middle Persian ones, Islamic ones (above all, Tabarī and Ferdowsī) and Armenian ones (especially Agathangelos and Movses Khorenats’i). These are the sources mostly used by modern scholars.

In this post, I will use mainly one paper by a modern scholar:

- Ardaxšir and the Sasanians’ Rise to Power, by Professor Touraj Daryaee, from University of California, Irvine published in Anabasis: Studia Classica et Orientalia No.1 (2010).

Working with Perso-Islamic sources is difficult because the conception of writing history in these eastern cultures was different from the one prevalent in the Graeco-Roman world. The renowned American Iranologist R.N.Frye notice time ago how, in these histories, facts and people are always made to fit into preexisting patterns, usually of religious or cultural origin. For example, Darius I was helped by seven Persian families to overthrow the “false king” Gaumata, Aršak I entered the Iranian plateau with a following of seven clans, and there were supposedly seven great “Parthian” clans during the Sasanian era.

The origins of the Sasanian family are surrounded in mystery, as there are scarcely two ancient sources, eastern of western that agree between them. Graeco-Roman and Armenia sources are markedly hostile to the Sasanians for historical reasons and seem to compete between them to give Ardaxšir I the humblest origins possible:

- Agathias (VI century CE) mentions that Ardaxšīr’s mother was married to Pābag whose lineage was obscure, but whose profession was a leather worker, while Sāsān was supposedly a soldier who spent the night at the house of Pābag, and Pābag then gave his wife to Sāsān.

- George Syncellus (IX century CE) stated that Ardaxšīr was an unknown and undistinguished Persian.

- George of Pisidia (VII century CE) mentioned that he was a slave by station.

- John Zonaras (XII century CE) said that he was from an unknown and obscure background.

Meanwhile, Tabarī and Ferdowsī both stated that Ardaxšir I came from aristocratic origins, from among the nobility of Pārs. Most scholars tend to take Tabarī’s account as authentic or more acceptable; in it Pābag was the son of Sāsān, while the VI century Middle Persian book Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšīr ī Pābagān, like Ferdowsī’s Šāhnāme both stated that Pābag’s daughter married Sāsān. And the Zoroastrian “sacred encyclopedia, the Bundahišn, gives another genealogy:

Ardaxšīr the son of Pābag, whose mother (is said) to be the daughter of Sāsān, son of Weh-āfrīd

The royal inscriptions of Ardaxšir I state that Pābag was his father, and Sāsān their “ancestor”, but without implying that Sāsān was Pābag’s father. And the inscriptions of Šābuhr I follow the same scheme; plus in both cases Sāsān is not called “king”, but merely “lord”, while Pābag is called “king”. Then, why did the family call themselves “Sasanians”, if Sāsān was such an obscure character? If that was not enough, Sāsān is a very rare name in western and central Iran. Before Ardaxšir I, it’s completely unattested in Pārs, Media and Parthia and it only appears in “eastern Iran”, the large land area inhabited or ruled by Iranian peoples east of the Arsacid empire proper: Soghdiana, Bactria, Sakastan, etc.

Ardaxšīr of course claimed Sāsān as the patriarch of the dynasty. An ostraca was found in Central Asia by Soviet archaeologists in the late 1980s which contained the epigraphic form ssn designating Sāsān as a deity. But because of its absence in the Avesta and the Old Persian documents, it is difficult to know how it was related to the Zoroastrian religion. Recent scholarly research seems to show that the deity represents Sesen, an old Semitic god which is found in Ugarit as early as the second millennium BCE. Be that as it may, in the first century CE coins can be found in Taxila in Gandhara with the name Sasa, which may be connected to Sāsān because the emblem on the coin matches the "coat-of-arms" for Šābuhr I.

Tabarī mentions the mysterious Sāsān as the ruler and custodian of the Anāhīd fire-temple at Istakhr, while his son Pābag became later king of Istakhr. This seems to be in accordance with the ŠKZ inscription, and so it represents the “official” position. Early Islamic sources based on Sasanian tradition emphasize the religiosity of Sāsān and his devotion and even mention him as an ascetic. In fact, Sāsān’s lineage is said to originate in India, the bastion of asceticism (according to Bal’ami). Only in this way could Ardaxšīr claim to have both priestly and royal lineage, meaning the story of Pābag as the king of Istakhr marrying the daughter of the priest (Sāsān) of the most important fire-temple at Istakhr. It is in this manner that Ardaxšīr could manufacture the double (king-priest) lineage topos which is such an important part of Sasanian religious and political tradition. And it’s not surprising that in the priestly tradition the religious origin of Ardaxšīr is emphasized, becoming connected with royalty, while the epic / royal tradition such as the Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšīr ī Pābagān emphasizes the royal origin and then its connection with the religious tradition of Ardaxšīr.

Aerial photograph of the remains of Istakhr.

Some iconographical features of Pābag’s coinage and imagery have provided scholars with some clues, which could help to shed some light into this mess. On the earliest coinage of Pābag with his elder son, Šābuhr, his headgear is unlike any of the Arsacid or Persis kings. It is only Šābuhr who presents himself on the obverse wearing the headgear (the bejeweled kolah / kulaf) symbolizing kingship or political power. The royal narrative informs us that Pābag dethroned the king of Istakhr, Gozīhr (according to the East Roman historian Agathias, whose informant Sergius apparently had access to the royal Sasanian archives). Pābag however, had designated his elder son, Šābuhr, and coins were struck showing the two on either side. Ardaxšīr did not accept this and removed his brother and those who stood before him and subsequently had coins minted in the image of his father and himself. But in the joint coinage of Ardaxšīr-Pābag, the father bears the kingly crown of Persis.

Silver drachm with Šābuhr (wearing the bejewelled kolah of Persian kings) in the obverse and his father Pābag in the reverse, wearing what scholars believe to be some kind of priestly headgear.

Silver drachm with Ardaxšīr in the obverse and his father Pābag in the reverse, wearing this time the royal kolah.

Drawing of a graffito from Persopolis assumed by scholars to represent Pābag.

In several extant sources sources Pābag is said to have been the priest of the fire-temple of Anāhīd at the city of Istakhr and this must have been a stage for the rallying of the local Persian warriors who were devoted to the cult of this. Pābag’s priestly function can also be seen in an extant graffito from Persepolis. Or could it be that the inability of the Persian royalty in the face of Arsacid power caused a priest-king to take the lead and revolt? This is a difficult question to answer, but it would not be the only time in the history of Iran that a holy man or religious leader rose up and attempted the conquest of the Iranian Plateau. Sāsān and Pābag were the priests / caretakers of the Anāhīd fire-temple at Istakhr and so Pābag’s function in relation to the fire-temple may have given backing to Ardaxšīr’s claim to rulership after the initial civil wars.

Anāhīd is important, since she was an object of devotion for heroes, warriors and kings in the Zoroastrian sacred text, the Avesta (for example in Yašt V, Ābān Yašt). During the Achaemenid period, in the beginning of the fifth century BCE, Artaxerxes II also worshipped Anāhīd (Anahita) along with Mīhr (Mithra) and Ohrmazd (Ahurā Mazdā). Thus, her cult must have been an old one in Persis and the temple may have been a location where the Persian tradition was kept alive. Her warlike character was the symbiosis of ancient Near Eastern (Ištar), Hellenic (Athena) and Iranian traditions which was used to legitimate kingship in the Sasanian period.

The goddess Anāhīd in a Sasanian silver jar.

Scholars may never know who Sāsān really was but his dual function of priest-king of Persepolis-Istakhr seems to be a well-established tradition. Daryaee suggests that if Pābag was anyone of rank, he was a local ruler at best, taking Tabarī’s assertion that he ruled a small area by the salt lake of Bakhtagān to the south of Istakhr the south called Khīr. And it's Pābag who first aspired to rule in Istakhr and took it over with his elder son Šābuhr, and not by the order of Ardaxšīr as Tabarī wrote. To Daryaee, this is made clear by Pābag’s coins with his elder son, Šābuhr.

Lake Bakhtagān.

Daryaee also notices Pābag’s name as an important pointer to his religious function as Pābag is a hypocrastic from Pāb, which means “father” in Middle Persian. Furthermore, Ardaxšīr at the time may have been in the south at Dārābgird far away from the Pābag-Šābuhr takeover of Istakhr. Daryaee suggests Ardaxšīr was an usurper in his own family who upon seeing his father taking charge of Istakhr and nominating his elder son and the brother of Ardaxšīr, began his campaign initially not against the Arsacid king Ardawān, but against his own father and then brother.

Daryaee points out that the German scholar Michael Alram suggested that Šābuhr and Ardaxšīr could have been portraying the dead image of Pābag on their early coinage. If so, then Ardaxšīr was only rebelling against his own brother. This could also explain why Ardawān did not send troops at first to meddle in the family feud. Again, these are only mere speculations and show that Ardaxšīr probably did not have a strong claim to any throne and was not in line for rulership.

When Ardaxšīr finally became the sole ruler of Iran, he constructed an elaborate genealogy which is captured in the late book Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšīr ī Pābagān:

Ardaxšīr the Kayānid, the son of Pābag, from the race of Sāsān, from the family of King Dārāy.

When looking at this line, Daryaee notices that every possible connection to divinity, royalty and nobility was being exploited by Ardaxšīr, which to him likely suggests that he was heir to none of them! The Kayānid dynasty in the Avesta, the mysterious protective deity Sāsān, and the connection to Dārāy (probably the conflation of the Achaemenids, Darius I and Darius III, and the kings of Pārs, Dārāyān I and Dārāyān II) all suggest to him that the first Sasanian king falsified his lineage. Ardaxšīr’s falsified connections, however, would have given him the prestige of being the first human to be shown receiving the diadem of rulership from Ohrmazd, something that was never shown in Achaemenid reliefs. A noble Persian would not have needed to be shown receiving the diadem from Ohrmazd; only an upstart would be in need to make the claim of being from the race of the yazdān. Looking at the early Sasanian rock reliefs, they show the king and the gods as having similar physical features, size, clothes, horses and harnesses. In terms of proportion, the Sasanian king is an exact mirror image of the yazatas / yazdān.

Perhaps it’s because of this “sacrilege” that some Zoroastrian texts like the Dēnkard and the Nāme-ye Tansar (Letter of Tansar) questioned Ardaxšīr’s legitimacy and his attempt at changing the tradition.

Perso-Arabic sources state that Ardaxšīr was the argbed (castellan) of Dārābgird in eastern Pārs when he began his campaign. However, the earliest physical evidence for Ardaxšīr can be found at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah (literally meaning “the Glory of Ardaxšir”, a city founded by him, near modern city of Fērōz-ābād, also known in late Sasanian and early Islamic times known as Gōr), on the southern fringes of Pārs. Daryaee thinks that it is from here, far from Khīr, the stronghold of Pābag, and Istakhr, the stronghold of the kings of Pārs, and still further away from the king of kings, Ardawān, that Ardaxšīr began his campaign. Daryaee thinks that Ardaxšīr moved from the remote Dārābgird to Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah which was behind the mountains and still defensible, but closer to the center of power in Persis, Istakhr, when Pābag’s revolt took place against the king of Pārs at Istakhr. However mountainous the road from Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah to Istakhr is, it’s still an easier route to traverse than from Dārābgird to Istakhr.

Remains of Dārābgird.

Remains of Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah, the city founded by Ardaxšīr I. Notice how both it and Dārābgird are built following a circular plan.

Superimposed sketch of the main streets, gates and roads of Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah.

Ardaxšīr’s beginnings may be connected to his first rock-relief which shows him receiving the diadem of rulership from Ohrmazd in front of his retinue at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah. Based on the date supplied by Šābuhr I’s inscription at Hajjīābād, Daryaee agrees with the German scholar Josef Wiesehöfer that the year 205/206 CE (which Šābuhr I chose as the beginning of the Sasanian era) does not mark the date of Ardaxšīr’s uprising but rather Pābag’s rebellion and movement from Khīr to Istakhr. This date coincides with the rule of the Arsacid king Walāxš V (192–207 CE) and the wars with the Roman emperor Septimius Severus.

As we have seen in previous posts, the Arsacids were not only involved in a bitter war with the Romans, but also with dynastic squabbles and provincial revolts. Septimius Severus, first in 196 CE, and then again in 198 CE invaded the Arsacid realm and was able to sack Ctesiphon. At the same time, we hear of the revolt by the Medes and the Persians against the Arsacid king in the Syriac Chronicle of Arbela which caused internal problems. The kings of Pārs could not rely on their Arsacid overlords anymore to support them in the face of local uprisings, such as that of Pābag.

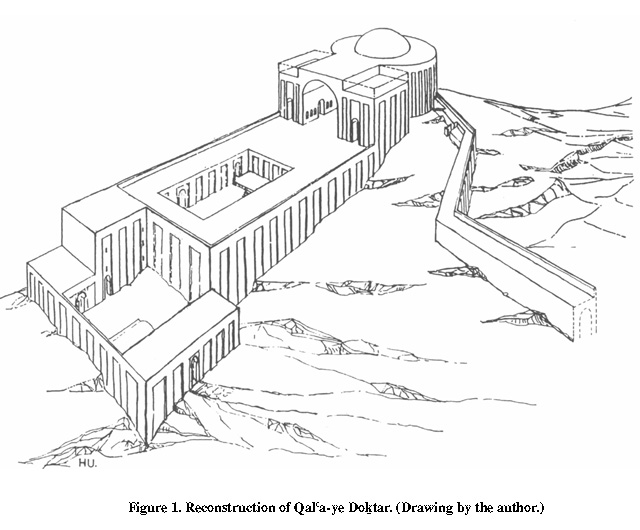

Daryaee is reluctant to accept the “official” version of history where according to Tabarī, Ardaxšīr was the argbed of Dārābgerd at this time and told his father Pābag to revolt against the Arsacids in 211/212 CE. To him, it’s more probable that between 205/206 and 211/212 CE Pābag had taken the throne at Istakhr and then chosen his eldest son Šābuhr as the heir. Ardaxšīr as an act of rebellion would then have moved from Dārābgerd to Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah and built himself a fortification from where he could launch his attack against his elder brother when Pābag died.

Ardaxšir’s first investiture rock-relief at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah.

Ardaxšir’s rock-relief at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah would then have been the symbol of his rebellion against his father, or more probably against his brother. Pābag must have died sometime before 211/212 and so by this date both Ardaxšīr and Šābuhr minted coins with the title of “king,” with the image of their recently deceased father on their coins. Daryaee also cites the important notice in the Zainu’l-Akhbar (a chronicle written in the XI century at the Ghaznavid court by Abū Sa’id al-Dahhāk) which to him seems to corroborate the thesis that Ardaxšīr indeed proclaimed himself king in 211/212 CE. According to the Zainu’l-Akhbar, when Ardaxšīr began his conquest Ardawān came to face him. What´s noteworthy to Daryaee is that the text states:

and twelve years had passed from the rule of Ardaxšīr when he killed Ardawān.

This clearly places Ardaxšīr’s claim to kingship and local investiture (at Istakhr or Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah) in 211/212 CE. The event of 211/212 CE which is the defeat and death of his elder brother Šābuhr also most probably coincided with his coronation relief at Naqš-e Rajab and the coinage that Ardaxšīr minted without his father’s image.

Ardaxšīr's "second" investiture relief, at Naqš-e Rajab near Istakhr.

Between 211/212 CE and the defeat of the Arsacid ruler Ardawān in 224 CE Ardaxšīr consolidated his power in the province of Pārs and the adjoining regions. In 216/217 CE he would certainly begin his propaganda campaign against the Arsacids as their prestige had been marred by the Roman actions at the Arsacid family sanctuary. How could a dynasty who was not even able to protect their own family be able to defend the Iranians? The kings of Pārs had been defeated by 211/212 and others a bit later as they may have been involved in aiding the Arsacid king of kings at Nisibis and therefore would have been ill prepared to fight the upstart. Ardaxšīr might have felt that a new house had to wrest away control of the royal throne, as the old one (the Arsacids) had been soundly humiliated. Daryaee also adds that apparently other brothers of Ardaxšīr were also worrisome to him and he had them killed at this time. Once he had the province of Persis and the adjoining regions under control he began to call himself “King of Iranians,” (šāh ī ērān) in his coinage.

Gold coin of Ardaxšīr I as “King of Iranians,” (šāh ī ērān).

Thus, he still refrained himself from taking the title of “King of Kings”, which would’ve been an open defy to Ardawān V. The šāh ī ērān title would probably refer to his conquest of Pārs and the wresting of Istakhr from the hands of the local rulers and those in his family who contended for his rule over it. According to Daryaee, it’s then that he had his rock-relief at Naqš-e Rajab, close to Istakhr, carved. Thus, one may surmise that the Naqš-e Rajab relief represents his victory over the kings of Pārs and the control of Istakhr as the center. The investiture scene is at the center of this event. That may well be the reason that Ardawān is still not under the hoof of Ardaxšīr’s horse on this relief, as he is at the Naqš-e Rustam relief. The importance of the local kings also made Ardaxšīr mindful to respect them as seen in the iconographical remains of this period. He also co-opted them into his genealogy and adopted their characteristic dress and headgear, thus representing himself as the continuer of the old Persian tradition existing at Istakhr.

Having consolidated his power in Pārs and having subdued the kadagxwadāyān “petty-lords”, he conquered adjoining regions which would have alarmed Ardawān. Then the fateful battle of Hormozdgan in 224 CE brought the defeat and death of Ardawān and brought about a new phase of Ardaxšīr’s rule. The Battle of Hormozdgan was carved in the location where he rose up in Pārs, at Ardaxšīr-Xwarrah. By then he could claim to be the “King of Kings of the Iranians”, and he reflected this in his coinage.

Silver drachm of Ardaxšīr I as King of Kings of Iran.

Last edited: