24.1 THE RISE OF THE ILLYRIAN EMPERORS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ROMAN RECOVERY.

Any political system based on the rule of a single leader has a key weakness: the ability of the ruler to adapt themselves to the circumstances and requirements of their time. This was as true for the Sasanian empire as for the Roman empire. After the death of Šābuhr I, we can see a reversal in the roles and circumstances of the two empires.

Ardaxšīr I and Šābuhr I had benefitted from a prolonged period of time in which the Roman empire had been pronged into an ever worsening political, military, demographic and military crisis, which reached its nadir in the 250-270 CE year span. Especially between 260 and 270 CE, the Roman empire was put against the ropes metaphorically speaking, and found itself fighting for its very survival, split into three different “empires”.

The first two energetic Sasanian kings had played themselves an essential part in plunging Rome into this deep crisis, as their constant attacks in the Near East had inflicted considerable stress into the Roman political and military system. If we (arbitrarily, because we could also date its start at an earlier date like the murder of Commodus; I myself prefer this option) make the start of the crisis coincide with the murder of Severus Alexander in 235 CE and its end (less arbitrarily, as this date is accepted by almost everybody) with the accession of Diocletian in 284 CE, it took the Roman political and military elites almost 50 years to get the situation under control, almost risking the collapse of the empire in the meantime.

The deaths of several emperors (and the accompanying usurpations) had been directly caused, or at least strongly influenced by their defeats in the East or by their inability to cope with what the Romans perceived as “Sasanian aggression” in that theater: Severus Alexander, Maximinus Thrax, Gordian III, Trebonianus Gallus, Valerian. And the Roman campaigns and military disasters in the East had also forced an increasingly beleaguered Roman state to shift ever more troops to the East, weakening the long European border of the empire. The collapse of the Rhenish-Raetian border in the 260s CE can be directly linked to the sending of a strong army headed by Valerian to the East at the start of his reign.

The joint reign of Valerian and Gallienus saw finally the fist signs that the Roman elite was starting to think “outside the box” and that it was willing to try some radical reforms. It’s almost sure that this was not part of any kind of plan, but that the crisis had reached such levels that the elite had hit the “panic” button and ad hoc solutions were being implemented on a random basis (it’s not even clear if they were intended as permanent at first). An example of an innovation that did not become a permanent one was the concentration of most of the cavalry in a single central army under Gallienus’ general Aureolus, based at Mediolanum, which together with the central reserve which had been based at Rome until then and selected vexillationes from the border legions was to act as a central reserve directly under the emperor’s command, to give him the upper hand firstly against usurpers and secondly against any “barbarian” raids into Italy and thirdly against the splinter Gallic empire led by Postumus.

But the existence of a proper “central” army directly under the emperor’s command was an innovation (well, partial innovation, a central reserve had already existed before Gallienus, but this ruler turned it into a proper permanent army designed to be deployed as a unified force in campaign) that stuck; this army received the name of comitatus (from Latin comes, “companion”, thus implying “the companions of the emperor”). Another key innovation introduced by Gallienus and which was to have very far-reaching consequences was his promotion to the upper ranks of military command of soldiers of very humble origins, which led within a very short space of time to the complete disappearance of the old senatorial and equestrian elite from the upper command posts. Today scholars agree that the statement by the SHA that Gallienus banished senators from command posts by decree is yet another fabrication, but the fact is that this was a process that happened under Gallienus (but not by imperial decree). There would be still senators commanding armies under his successors, but they became an utter rarity.

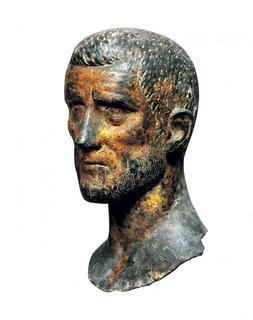

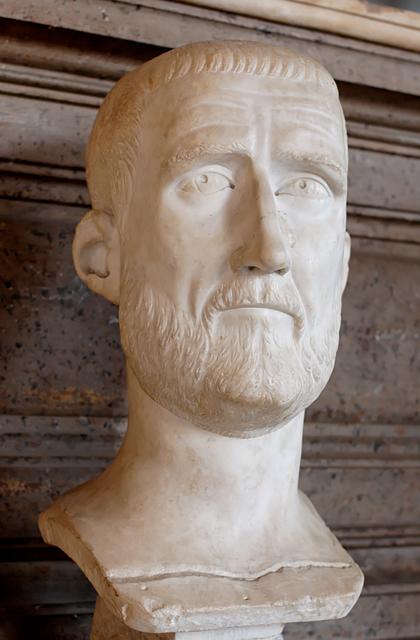

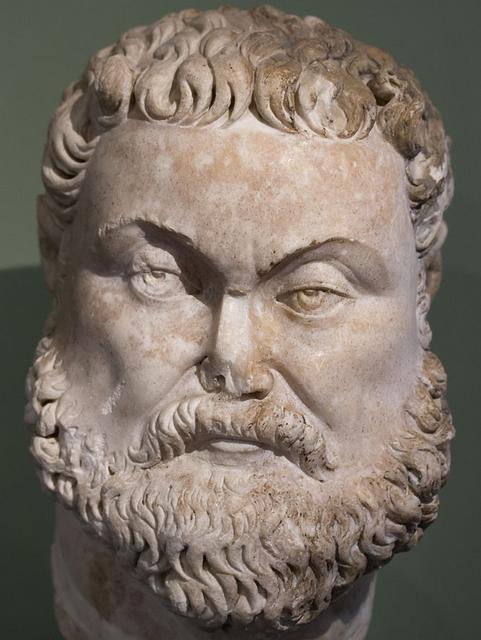

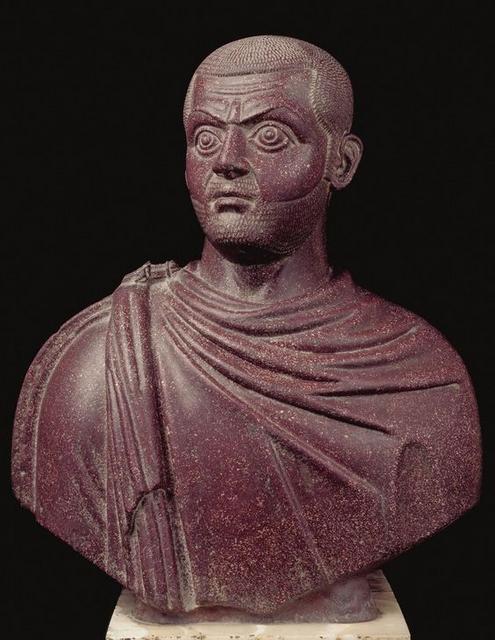

Bust of Gallienus as a middle aged man, probably dated to the end of his reign.

These new men were promoted by Gallienus solely on grounds of their military ability, and it’s remarkable that they all came from a very restricted geographical area: Lower Pannonia and Upper Moesia (thus their appellation of “Illyrians”), an area which contained no large cities, with its main center being Sirmium. Probably because the Danubian army was the only large army that remained loyal to Gallienus (the British, Rhenish and Raetian armies had defected to Postumus, and the eastern armies were controlled first by the Macriani and later by Odaenathus). But still, this does not explain why they came from such a specific area; surely these two provinces were important recruitment sources, but so were Thracia or Upper Pannonia.

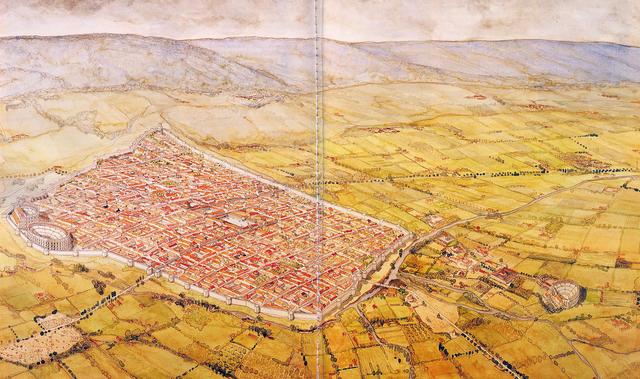

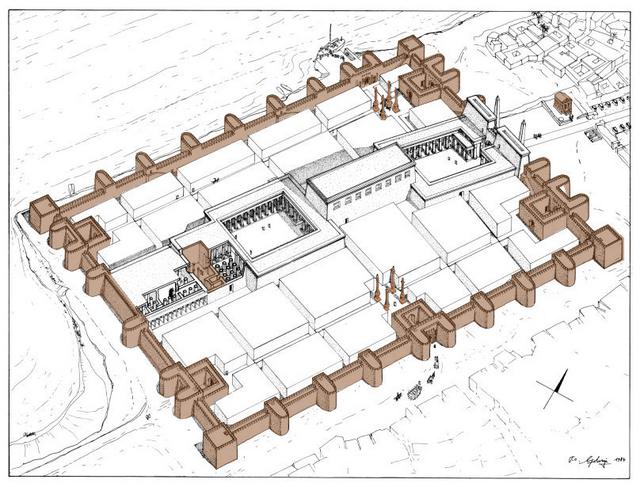

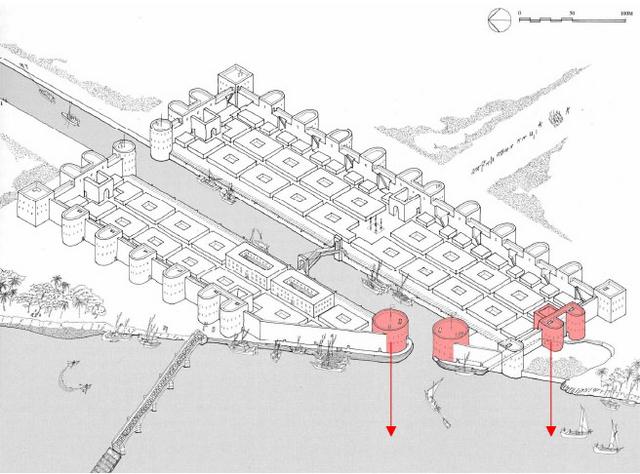

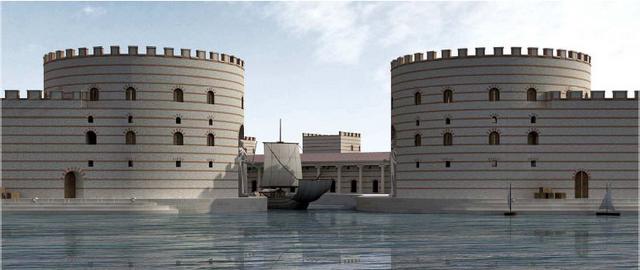

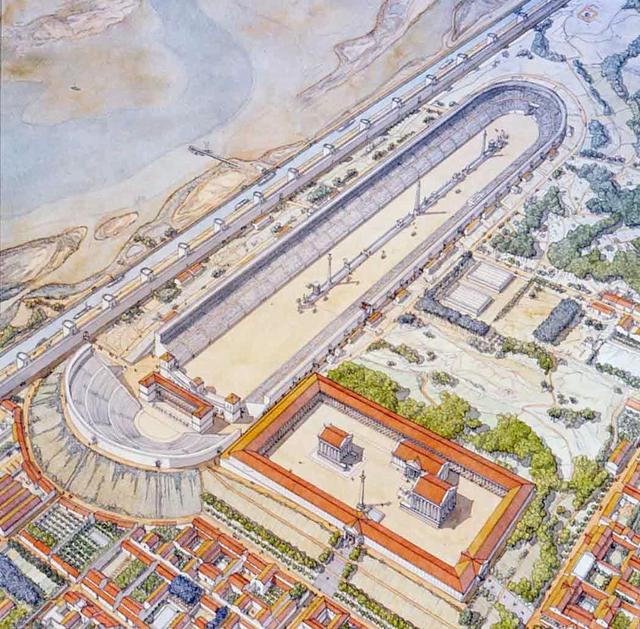

Plaster model of Sirmium, modern Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia, on the banks of the Savus river (modern Sava).

These Illyrian officers were all promoted through a new elite unit created by Gallienus, the candidati (from Latin candidus, meaning “white”, because according to ancient sources they wore white garments). This elite cavalry unit was not a ceremonial unit but a real battle unit and also a bodyguard unit that accompanied the emperor at all times. Its members could expect quick promotion out of its ranks into higher command ranks both in the comitatus and the armies that remained at the borders. Scholars believe that these Illyrian officers became a tightly knotted and closed group within the candidati (Ilkka Syvänne even uses the term “Illyrian Mafia” to refer to them, while other scholars like David S. Potter use the somewhat more subdued expression “Illyrian Junta”), which effectively managed to cope all senior positions, to the extent that almost all the emperors for the next century would come from this group (Flavius Constantius, the father of Constantine the Great, also belonged to it).

These men lacked the ideological baggage that respect for former tradition imposed on the older elites, and once they gained access to power, two things happened. First, a dramatic improvement in the fortunes of Roman arms (at last the Romans had managed to put the leadership of the army into the hands of professionals, which was the logical culmination of the reforms of Gaius Marius at the end of the II century BCE) and an acceleration in the rate of reforms, with an ever-diminishing respect towards tradition. Gallienus was to be the penultimate emperor of senatorial descent, and the last emperor who resided during a significant part of his reign in the city of Rome.

Gallienus managed to survive 8 dramatic years between 260 and 268 CE thanks to these emergency measures and the loyalty and skills of these new Illyrian commanders. But in the end, these homini novi adopted also the customs and practices of the old elite and decided to remove Gallienus from power. The mid-260s CE had seen a relative stabilization of the situation in Gallienus’ part of the empire, but this calm was not going to last. In 267 CE, the Goths and Heruli launched again large-scale attacks against the Roman Balkan and Anatolian provinces. While Gallienus was busy in the Balkans fighting against the Goths and Heruli, he managed to repeal the latter at the river Nestus, but in April 268 CE his general Aureolus, his most important and trusted commander who commanded the imperial cavalry army based at Mediolanum, began issuing coins in the name of the Gallic emperor Postumus. In the summer of 268 CE, Gallienus’ army entered northern Italy and marched towards Mediolanum to end with this rebellion; Aureolus blocked the advance of Gallienus’ army at one of the bridges on the river Adda (later called pons Aureoli, modern Pontirolo), but Gallienus won the battle. Aureolus quickly retreated inside the walls of Mediolanum, and Gallienus besieged the city.

While once more the Romans were busy fighting amongst themselves, the Goths and Heruli were left free to plunder at leisure. In Anatolia it had to be Odaenathus and his son Heraclianus who intervened to restore the situation, this meant a further enlargement of the Palmyrene sphere of influence into northern and western Asia Minor. While they were campaigning there, in the winter of 267/268 CE Odaenathus and his son and heir Heraclianus were murdered in what appears to have been an internecine “vendetta” within the Palmyrene royal family; some ancient sources like Petrus Patricius and John of Antioch attribute the responsibility for the murder plot to Gallienus. If this was indeed Gallienus’ doing, he did not reap any benefits from the murder; control in Palmyra (and by extension in the whole Roman East) was assumed by Odaenathus’ widow Septimia Zenobia, in the name of their remaining son Vaballathus, onto whom his mother invested all the titles which had been once held by his father in an action of dubious legal status; except for the titles of Ras and Exarch, and the self-assumed title of rex regum, these titles had been given to Odaenathus by Gallienus, and so his son could only have received them from Gallienus too (offices were not hereditary in the Roman res publica). Instead of bringing the East back under Gallienus’ command, the murder marked a decisive step in the increasingly autonomous and independent tendencies of Palmyra.

In the meanwhile, Gallienus was besieging Aureolus at Mediolanum; before the siege was complete and according to Udo Hartmann’s dates and reconstruction of events, Gallienus was murdered at the end of August 268 CE by a cabal of his Illyrian officers; he was 50 years old. The plotters included generals M.Aurelius Valerius Claudius (Aureolus’ successor as commander of the cavalry), Lucius Aurelius Marcianus (whom Gallienus had left in command of the forces in the Danube, and who was not present at Mediolanum), Lucius Domitius Aurelianus (the future emperor), Aurelius Heraclianus (the Praetorian Prefect) and Cecropius, commander of the Dalmatian cavalry. This included practically all the senior commanders of Gallienus’ army.

Immediately after the murder, the troops of the besieging army acclaimed as augustus one of the members of the conspiracy: Marcus Aurelius Valerius Claudius, which has gone down in Roman history as Claudius II or Claudius Gothicus. His origins are extremely obscure; he came either from Sirmium in Lower Pannonia or Naissus in Upper Moesia (the sources are contradictory about it). Soon hereafter, Aureolus left the besieged city and presented himself in front of the new emperor, presumably to ask for clemency (or because he had taken part in the murder and this was part of the arrangement); according to Zosimus he was conveniently “killed by Claudius’ soldiers”. Claudius also ordered the execution of his fellow conspirator Cecropius and possibly also Heraclianus and forced the Senate (which had hurried to order the execution of Gallienus’ brother, wife and son in Rome) to deify Gallienus in order to distance himself as much possibly from the murder of his predecessor. On the other hand, Aurelian enjoyed a bright career during Claudius’ reign, becoming commander of the cavalry, the post previously occupied by Aureolus and Claudius himself.

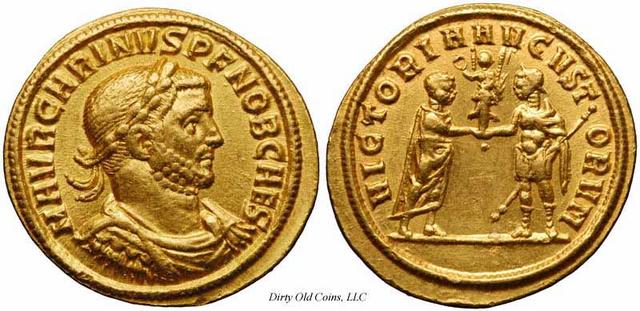

Aureus of Claudius Gothicus. On the reverse, GENIVS EXERCI(TVS), a clear allusion to the way he rose to power.

Claudius’ most urgent task was to go back to the Balkans and finish the task that Gallienus had left unfinished, expelling from there the Goths and their allies. They had launched a new large-scale amphibious attack against the Roman Balkans, gathering forces from the Goths and their allied and subject peoples like the Gepids, Peucini and Heruli. The SHA and Zosimus give enormous (and quite unbelievable) numbers for this second wave of invaders (325,000 men and 2,000-6,000 ships). Still, these numbers can be taken as an inkling that the Gothic force was huge, larger perhaps than anything the Goths had ever before assembled against the Romans.

According to ancient sources (which are quite confusing and contradictory), this force headed to the Bosporus after failing to storm Marcianopolis, where it suffered man casualties due to the strong currents of the Straits and perhaps to Roman naval counterattacks. They attacked and took Byzantium and Chrysopolis, and managed to get into the Aegean, where some detachments plundered as far away as Crete. But the main body attacked the coast of what’s now northern Greece, and besieged Thessalonica and Cassandreia.

But his Gothic campaign had to be delayed, because once again the Alamanni had crossed the Alps and invaded Italy. Claudius intercepted and defeated the invaders at the battle of lake Benacus (lake Garda). The chronology for all these events is unclear. Patricia Southern dates the battle of lake Benacus at the late fall of 268 CE, but many other authors date it to late winter or the spring of 269 CE. Once the Alamannic threat to Italy had been thwarted, Claudius and his army marched to the Balkans. The campaign against the Goths and their allies was to be extremely hard and difficult and would occupy the rest of Claudius II’s reign (a year and eight months).

Claudius left behind in Italy his brother Marcus Aurelius Claudius Quintillus with an army in case that the Gallic Empire tried an attack against the peninsula, while he and Aurelian joined forces with Marcianus in the Balkans, possibly in Upper Moesia.

Upon hearing of the approach of Claudius’ army, the Goths lifted both sieges and marched into the interior, laying waste to northern Macedonia in their wake. Apparently, Claudius had detached the cavalry of his army under Aurelian’s command and sent him forward to shadow and harass the Goths in their northwards march; through skilled attacks and ambushes Aurelian managed to inflict serious losses onto the Gothic force with very few casualties to his own force. Finally, the Gothic army clashed against Claudius’ main army (reinforced by Aurelian’s cavalry) near Naissus in Upper Moesia, in an indecisive encounter that saw many losses on both sides. The battle was not decisive in that it did not cripple the Gothic force, but it severely maimed it and stopped its northbound advance. Unable to retreat across the Danube to their homeland, the Goths were forced to retreat back south across devastated territory, and soon hunger began to take its toll, and worse still a plague broke between their ranks. Once again, they were constantly harassed by Aurelian’s cavalry at short quarters, while Claudius’ main army shadowed them from a distance. The Goths tried to find another way north and out of devastated territory by turning east into Thrace, but there Aurelian and Claudius by skillful maneuvering managed to trap and surround them in the Haemus Mons (the Balkan range). By then it was already winter (269-270 CE) and cold, lack of provisions and the plague were not only tormenting the Goths (who were trapped in the cold mountains, without access to foodstuffs) but also the Roman forces, where discipline began to break down in some unclear its.

Suva Planina, in southeastern Serbia. This was probably the place where the battle of Naissus took place. Today is a nature reserve, and it's crossed by the remains of the Roman Via Militaris, which ran between Singidunum (modern Belgrade) and Byzantium.

In this situation, the Goths who were certainly weakened, but whose fighting spirit had been not broken yet) attempted a desperate break out attack against the Roman encirclement. Allegedly, Claudius ignored Aurelian’s advice and tried to block the Gothic sally only with the infantry, and the result was almost a total disaster for Roman arms; only the swift intervention of Aurelian’s cavalry against the Gothic flanks and rear avoided a complete Roman rout. Many Goths managed to break from the encirclement and divided into smaller warbands who began to roam the countryside of Lower Moesia and Thrace looting it for booty and food. By this time, plague was affecting severely the Roman army and even the emperor himself, and Claudius retreated to his regional headquarters at Sirmium to try to recover. The task of cleaning Thrace and Lower Moesia of Gothic war bands fell to Aurelian, who spend most of the spring and summer of 270 CE doing so.

This campaign marked a watershed in the military status between Rome and the Goths, for although it did not break the military power of the Gothic confederation and it did not put an end to the fighting between both foes, it helped to stop for a whole century further large-scale Gothic attacks into Roman territory (of the kind that had begun at the end of Philip the Arab’s reign). Together with the inactivity of the Sasanians in the East, this gave a much-needed balloon of oxygen to the Roman empire, because the two worse enemies of Rome during the III century CE were now (at least temporarily) out of the scene. This would be essential for the Roman recovery, because although many enemies remained, none of them were of the same caliber.

Apparently, after winning all these victories Claudius took the titles of Gothicus Maximus and Germanicus Maximus, although it’s unsure if he managed to go back to Rome to celebrate a triumph, because while Aurelian was wrapping up things in the eastern Balkans, the Vandals and Sarmatians broke across the Roman border in the middle Danube in Upper and Lower Pannonia. In late August or early September 270 CE, Claudius II died at Sirmium of the plague (probably one of the last outbreaks of the Plague of Cyprian), and nominated his brother Quintillus as successor, who was promptly acknowledged as the new augustus by the Roman Senate.

Claudius’ reign would set a trend until the accession of Diocletian: tough, soldierly and short-lived emperors who ruled from the saddle as they displayed superhuman energy running from one border to another fighting assorted invasions and usurpers. These Illyrian emperors managed to stabilize the military situation somewhat but failed at restoring a viable and stable political regime able to guarantee the internal peace needed to allow the recovery of many devastated areas of the empire; only Diocletian would be able to succeed in this regard.

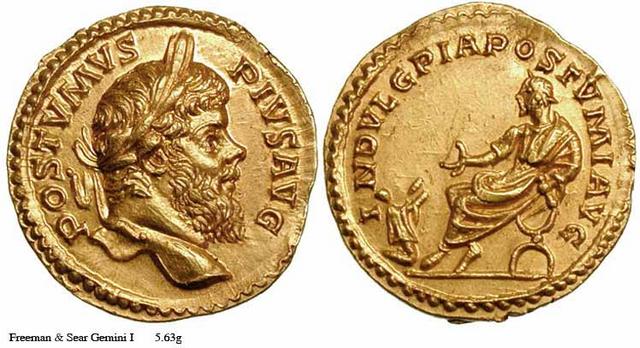

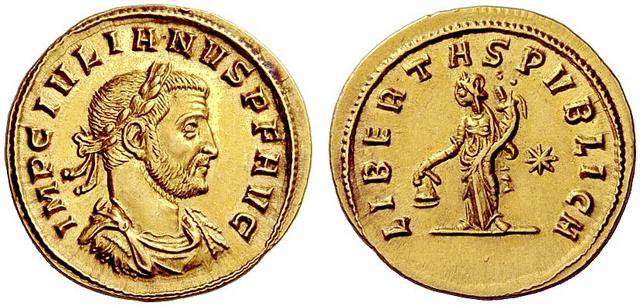

Aureus of Quintillus. On the reverse, the (somewhat premature) legend FIDES EXERCITI (loyalty of the armies)

Quintillus controlled the small army left in Italy to control threats from Gaul, but the largest part of the army was gathered in Pannonia to fight against the Vandals, and it acclaimed the commander of Claudius’ cavalry, Aurelian as augustus. Upon hearing the news and realizing that Aurelian was supported by most of the army, Quintillus killed himself at Aquileia and left the field free for Aurelian. The choice is not surprising, because most of the merit for Claudius’ victories against the Goths in the Balkans belonged in fact to Aurelian’s skillful leadership, and the soldiers of the Illyrian and Danubian armies were well aware of this fact.

The new emperor has gone down in history as one of the greatest Roman generals ever (more than deservedly), although in my opinion even if he was without any doubt a stellar commander, he was not as successful as an emperor, because even if he was able to win an impressive amount of victories, he failed to address properly the political and fiscal crisis that had played a capital role in the downward spiral of the Roman empire.

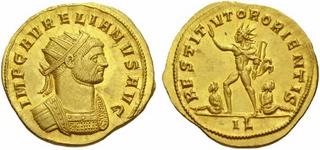

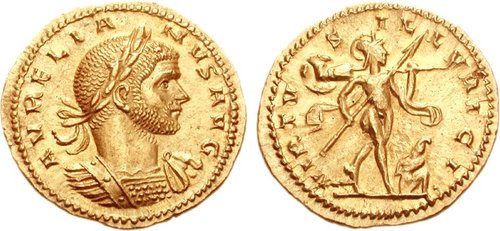

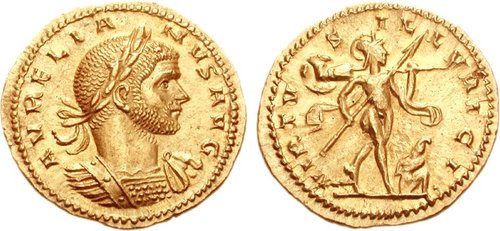

Aureus of Aurelian. On the reverse, VIRTVS ILLIRICI, in praise of the martial qualities of the Illyrian army.

Aurelian’s reign began with the emperor having to deal with military trouble, and this would be the trend for the four years it lasted, with the energetic Aurelian rushing from one troubled spot to another, playing the role of the “imperial fire fighter“ (like Gallienus and Claudius II before him). His first task was to finish the fight in Pannonia against the Vandals and Sarmatians, a task that kept him busy for the remainder of the year 270 CE. One of the scarce surviving fragments of Dexippus’ Scythica describes how Aurelian resorted to a mix of military action and negotiations to close the campaign in Pannonia. Although it’s unclear if he could achieve a satisfactory result, because in the winter of 270-271 CE the Alamanni and Iuthungi launched yet another major invasion across the upper Danube, crossed the Alpine passes and invaded the northern Italian plain unopposed, moving at great speed and crossing the Po river. Aurelian had to hurry to Italy from Pannonia, but in January 271 CE the Alamanni defeated him near Placentia, and Aurelian was forced to retreat back towards the Julian Alps; it’s probable that the emperor had been surprised by the speedy advance of the invaders and had moved quickly to intercept them with only part of his army (perhaps only the most mobile units), and when he intercepted the Alamanni he found himself badly outnumbered and was forced to retreat and wait for the rest of the army to join him. The Alamanni seized the opportunity and advanced south along the Via Flaminia, with the clear intention of attacking Rome itself. When the news reached the Urbs, panic ensued, but luckily for its inhabitants, Aurelian reacted with energy and speed. He gathered his forces and pursued them; he caught them at Fanum (modern Fano, in Romagna) and there he defeated them in pitched battle, although the Alamanni were not routed and they were able to retreat northwards in good order and crossed again the Po river near Ticinum (modern Pavia). After the fiasco of Placentia and the danger of an attack against Rome, Aurelian’s reputation was at stake, and he pursued the Alamanni and Iuthungi into the northern Italian plain. He cut their path of retreat on an open plain near Pavia, and in the battle that ensued Aurelian routed the completely and recovered all the booty and captives that his foes had plundered during their invasion. Only a small group was able to cross the Alps back into Raetia, but even this small force was pursued and destroyed by Aurelian. After this victory, Aurelian assumed the title Germanicus Maximus.

The city of Rome had suffered its second major invasion scare in a decade, and in a political gesture aimed at inspiring confidence to its inhabitants, Aurelian ordered the building of a new wall around the city, the first one to be built in Rome since the times of the legendary king of Rome Servius Tullius. The wall was a propaganda gesture more than anything, because its disproportionate length, the huge population of Rome and the lack of reliable water springs within the city meant that the city was indefensible against a serious enemy, but it would serve to stop isolated “barbarian” war bands from plundering the city, giving time for relief army to be sent by the emperor.

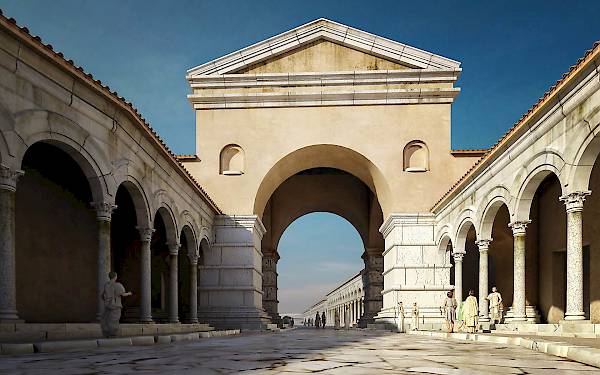

Aerial view of the Aurelian Wall in Rome; large tracts of it are still intact.

This decision was probably prompted by the unrest that beset Rome in the aftermath of the invasion scare. In the summer of 271 CE, the workers of the Roman mint revolted, and this soon translated into widespread riots across the city. Some scholars link this revolt to the decision by Aurelian to reform the currency, which had reached its absolute nadir during the early 270s CE. Part of the reform included the decentralization of minting from big mints as the one in Rome into smaller ones closer to the borders (where the soldiers had to receive their pay), like Siscia in Illyricum (modern Sisak, in Croatia). And the guild of minters seems to have taken the news quite badly, the rioting lasted several days and led to thousands of deaths in the fighting. The SHA’s account tells us that Aurelian had the revolt put down by the sword, killing thousands in the process, and killing also a large part of the city’s leadership (i.e. the senators); this is just another example of the SHA’s view of Aurelian as a brutish, bloodthirsty tyrant, which finds an echo in other Latin sources, especially in Ammianus Marcellinus, with his quote that Aurelian “fell upon the rich like a torrent”. From these examples it’s clear that the senatorial tradition was quite hostile towards Aurelian, but Zosimus presents a much milder view of Aurelian, reflecting probably the opinion of (now lost) III century CE Greek sources. In his efforts to pacify the Urbs before departing for the East, apart from ordering the building of the Aurelian Wall, he ordered that from that on the food dole to the Roman populace would also include pork, apart from bread and olive oil (all at the state’s expense).

But Aurelian had no time to rest on his laurels, because alarming news arrived from the Balkans and the East. In the Balkans, the Goths had attacked Dacia and the lower Danube once again, and Aurelian moved quickly against them in early 272 CE, winning his third campaign in less than two years. After this victory, he took the name Gothicus Maximus and took a drastic decision regarding to the defense of the Danubian border: he ordered the abandonment of Dacia and the evacuation of all the military and civilian personnel, as well as any civilians who wanted to remain under Roman rule. This was an extraordinarily risky decision for any Roman emperor to take, because abandoning conquered territory was anathema in Roman political culture, especially a territory that had been Roman for more than a century and a half, but there was already the recent precedent of the Agri Decumates, and from a strategic point of view the decision made sense for a beleaguered empire that had been fighting desperately on the defensive for decades. It shortened drastically the border to defend, abandoning a very exposed territory that anyway was scarcely populated and Romanized and had to be defended with a large garrison of two complete legions and more than 10,000 auxiliaries. Pulled back behind the Danube, these forces would have to defend now a drastically shortened border.

This second Balkan campaign though was just a minor affair for Aurelian, because the major reason for his presence in the Balkans was that he was moving with his army to the East, where the political situation had reached a breaking point between Rome and Palmyra.

Any political system based on the rule of a single leader has a key weakness: the ability of the ruler to adapt themselves to the circumstances and requirements of their time. This was as true for the Sasanian empire as for the Roman empire. After the death of Šābuhr I, we can see a reversal in the roles and circumstances of the two empires.

Ardaxšīr I and Šābuhr I had benefitted from a prolonged period of time in which the Roman empire had been pronged into an ever worsening political, military, demographic and military crisis, which reached its nadir in the 250-270 CE year span. Especially between 260 and 270 CE, the Roman empire was put against the ropes metaphorically speaking, and found itself fighting for its very survival, split into three different “empires”.

The first two energetic Sasanian kings had played themselves an essential part in plunging Rome into this deep crisis, as their constant attacks in the Near East had inflicted considerable stress into the Roman political and military system. If we (arbitrarily, because we could also date its start at an earlier date like the murder of Commodus; I myself prefer this option) make the start of the crisis coincide with the murder of Severus Alexander in 235 CE and its end (less arbitrarily, as this date is accepted by almost everybody) with the accession of Diocletian in 284 CE, it took the Roman political and military elites almost 50 years to get the situation under control, almost risking the collapse of the empire in the meantime.

The deaths of several emperors (and the accompanying usurpations) had been directly caused, or at least strongly influenced by their defeats in the East or by their inability to cope with what the Romans perceived as “Sasanian aggression” in that theater: Severus Alexander, Maximinus Thrax, Gordian III, Trebonianus Gallus, Valerian. And the Roman campaigns and military disasters in the East had also forced an increasingly beleaguered Roman state to shift ever more troops to the East, weakening the long European border of the empire. The collapse of the Rhenish-Raetian border in the 260s CE can be directly linked to the sending of a strong army headed by Valerian to the East at the start of his reign.

The joint reign of Valerian and Gallienus saw finally the fist signs that the Roman elite was starting to think “outside the box” and that it was willing to try some radical reforms. It’s almost sure that this was not part of any kind of plan, but that the crisis had reached such levels that the elite had hit the “panic” button and ad hoc solutions were being implemented on a random basis (it’s not even clear if they were intended as permanent at first). An example of an innovation that did not become a permanent one was the concentration of most of the cavalry in a single central army under Gallienus’ general Aureolus, based at Mediolanum, which together with the central reserve which had been based at Rome until then and selected vexillationes from the border legions was to act as a central reserve directly under the emperor’s command, to give him the upper hand firstly against usurpers and secondly against any “barbarian” raids into Italy and thirdly against the splinter Gallic empire led by Postumus.

But the existence of a proper “central” army directly under the emperor’s command was an innovation (well, partial innovation, a central reserve had already existed before Gallienus, but this ruler turned it into a proper permanent army designed to be deployed as a unified force in campaign) that stuck; this army received the name of comitatus (from Latin comes, “companion”, thus implying “the companions of the emperor”). Another key innovation introduced by Gallienus and which was to have very far-reaching consequences was his promotion to the upper ranks of military command of soldiers of very humble origins, which led within a very short space of time to the complete disappearance of the old senatorial and equestrian elite from the upper command posts. Today scholars agree that the statement by the SHA that Gallienus banished senators from command posts by decree is yet another fabrication, but the fact is that this was a process that happened under Gallienus (but not by imperial decree). There would be still senators commanding armies under his successors, but they became an utter rarity.

Bust of Gallienus as a middle aged man, probably dated to the end of his reign.

These new men were promoted by Gallienus solely on grounds of their military ability, and it’s remarkable that they all came from a very restricted geographical area: Lower Pannonia and Upper Moesia (thus their appellation of “Illyrians”), an area which contained no large cities, with its main center being Sirmium. Probably because the Danubian army was the only large army that remained loyal to Gallienus (the British, Rhenish and Raetian armies had defected to Postumus, and the eastern armies were controlled first by the Macriani and later by Odaenathus). But still, this does not explain why they came from such a specific area; surely these two provinces were important recruitment sources, but so were Thracia or Upper Pannonia.

Plaster model of Sirmium, modern Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia, on the banks of the Savus river (modern Sava).

These Illyrian officers were all promoted through a new elite unit created by Gallienus, the candidati (from Latin candidus, meaning “white”, because according to ancient sources they wore white garments). This elite cavalry unit was not a ceremonial unit but a real battle unit and also a bodyguard unit that accompanied the emperor at all times. Its members could expect quick promotion out of its ranks into higher command ranks both in the comitatus and the armies that remained at the borders. Scholars believe that these Illyrian officers became a tightly knotted and closed group within the candidati (Ilkka Syvänne even uses the term “Illyrian Mafia” to refer to them, while other scholars like David S. Potter use the somewhat more subdued expression “Illyrian Junta”), which effectively managed to cope all senior positions, to the extent that almost all the emperors for the next century would come from this group (Flavius Constantius, the father of Constantine the Great, also belonged to it).

These men lacked the ideological baggage that respect for former tradition imposed on the older elites, and once they gained access to power, two things happened. First, a dramatic improvement in the fortunes of Roman arms (at last the Romans had managed to put the leadership of the army into the hands of professionals, which was the logical culmination of the reforms of Gaius Marius at the end of the II century BCE) and an acceleration in the rate of reforms, with an ever-diminishing respect towards tradition. Gallienus was to be the penultimate emperor of senatorial descent, and the last emperor who resided during a significant part of his reign in the city of Rome.

Gallienus managed to survive 8 dramatic years between 260 and 268 CE thanks to these emergency measures and the loyalty and skills of these new Illyrian commanders. But in the end, these homini novi adopted also the customs and practices of the old elite and decided to remove Gallienus from power. The mid-260s CE had seen a relative stabilization of the situation in Gallienus’ part of the empire, but this calm was not going to last. In 267 CE, the Goths and Heruli launched again large-scale attacks against the Roman Balkan and Anatolian provinces. While Gallienus was busy in the Balkans fighting against the Goths and Heruli, he managed to repeal the latter at the river Nestus, but in April 268 CE his general Aureolus, his most important and trusted commander who commanded the imperial cavalry army based at Mediolanum, began issuing coins in the name of the Gallic emperor Postumus. In the summer of 268 CE, Gallienus’ army entered northern Italy and marched towards Mediolanum to end with this rebellion; Aureolus blocked the advance of Gallienus’ army at one of the bridges on the river Adda (later called pons Aureoli, modern Pontirolo), but Gallienus won the battle. Aureolus quickly retreated inside the walls of Mediolanum, and Gallienus besieged the city.

While once more the Romans were busy fighting amongst themselves, the Goths and Heruli were left free to plunder at leisure. In Anatolia it had to be Odaenathus and his son Heraclianus who intervened to restore the situation, this meant a further enlargement of the Palmyrene sphere of influence into northern and western Asia Minor. While they were campaigning there, in the winter of 267/268 CE Odaenathus and his son and heir Heraclianus were murdered in what appears to have been an internecine “vendetta” within the Palmyrene royal family; some ancient sources like Petrus Patricius and John of Antioch attribute the responsibility for the murder plot to Gallienus. If this was indeed Gallienus’ doing, he did not reap any benefits from the murder; control in Palmyra (and by extension in the whole Roman East) was assumed by Odaenathus’ widow Septimia Zenobia, in the name of their remaining son Vaballathus, onto whom his mother invested all the titles which had been once held by his father in an action of dubious legal status; except for the titles of Ras and Exarch, and the self-assumed title of rex regum, these titles had been given to Odaenathus by Gallienus, and so his son could only have received them from Gallienus too (offices were not hereditary in the Roman res publica). Instead of bringing the East back under Gallienus’ command, the murder marked a decisive step in the increasingly autonomous and independent tendencies of Palmyra.

In the meanwhile, Gallienus was besieging Aureolus at Mediolanum; before the siege was complete and according to Udo Hartmann’s dates and reconstruction of events, Gallienus was murdered at the end of August 268 CE by a cabal of his Illyrian officers; he was 50 years old. The plotters included generals M.Aurelius Valerius Claudius (Aureolus’ successor as commander of the cavalry), Lucius Aurelius Marcianus (whom Gallienus had left in command of the forces in the Danube, and who was not present at Mediolanum), Lucius Domitius Aurelianus (the future emperor), Aurelius Heraclianus (the Praetorian Prefect) and Cecropius, commander of the Dalmatian cavalry. This included practically all the senior commanders of Gallienus’ army.

Immediately after the murder, the troops of the besieging army acclaimed as augustus one of the members of the conspiracy: Marcus Aurelius Valerius Claudius, which has gone down in Roman history as Claudius II or Claudius Gothicus. His origins are extremely obscure; he came either from Sirmium in Lower Pannonia or Naissus in Upper Moesia (the sources are contradictory about it). Soon hereafter, Aureolus left the besieged city and presented himself in front of the new emperor, presumably to ask for clemency (or because he had taken part in the murder and this was part of the arrangement); according to Zosimus he was conveniently “killed by Claudius’ soldiers”. Claudius also ordered the execution of his fellow conspirator Cecropius and possibly also Heraclianus and forced the Senate (which had hurried to order the execution of Gallienus’ brother, wife and son in Rome) to deify Gallienus in order to distance himself as much possibly from the murder of his predecessor. On the other hand, Aurelian enjoyed a bright career during Claudius’ reign, becoming commander of the cavalry, the post previously occupied by Aureolus and Claudius himself.

Aureus of Claudius Gothicus. On the reverse, GENIVS EXERCI(TVS), a clear allusion to the way he rose to power.

Claudius’ most urgent task was to go back to the Balkans and finish the task that Gallienus had left unfinished, expelling from there the Goths and their allies. They had launched a new large-scale amphibious attack against the Roman Balkans, gathering forces from the Goths and their allied and subject peoples like the Gepids, Peucini and Heruli. The SHA and Zosimus give enormous (and quite unbelievable) numbers for this second wave of invaders (325,000 men and 2,000-6,000 ships). Still, these numbers can be taken as an inkling that the Gothic force was huge, larger perhaps than anything the Goths had ever before assembled against the Romans.

According to ancient sources (which are quite confusing and contradictory), this force headed to the Bosporus after failing to storm Marcianopolis, where it suffered man casualties due to the strong currents of the Straits and perhaps to Roman naval counterattacks. They attacked and took Byzantium and Chrysopolis, and managed to get into the Aegean, where some detachments plundered as far away as Crete. But the main body attacked the coast of what’s now northern Greece, and besieged Thessalonica and Cassandreia.

But his Gothic campaign had to be delayed, because once again the Alamanni had crossed the Alps and invaded Italy. Claudius intercepted and defeated the invaders at the battle of lake Benacus (lake Garda). The chronology for all these events is unclear. Patricia Southern dates the battle of lake Benacus at the late fall of 268 CE, but many other authors date it to late winter or the spring of 269 CE. Once the Alamannic threat to Italy had been thwarted, Claudius and his army marched to the Balkans. The campaign against the Goths and their allies was to be extremely hard and difficult and would occupy the rest of Claudius II’s reign (a year and eight months).

Claudius left behind in Italy his brother Marcus Aurelius Claudius Quintillus with an army in case that the Gallic Empire tried an attack against the peninsula, while he and Aurelian joined forces with Marcianus in the Balkans, possibly in Upper Moesia.

Upon hearing of the approach of Claudius’ army, the Goths lifted both sieges and marched into the interior, laying waste to northern Macedonia in their wake. Apparently, Claudius had detached the cavalry of his army under Aurelian’s command and sent him forward to shadow and harass the Goths in their northwards march; through skilled attacks and ambushes Aurelian managed to inflict serious losses onto the Gothic force with very few casualties to his own force. Finally, the Gothic army clashed against Claudius’ main army (reinforced by Aurelian’s cavalry) near Naissus in Upper Moesia, in an indecisive encounter that saw many losses on both sides. The battle was not decisive in that it did not cripple the Gothic force, but it severely maimed it and stopped its northbound advance. Unable to retreat across the Danube to their homeland, the Goths were forced to retreat back south across devastated territory, and soon hunger began to take its toll, and worse still a plague broke between their ranks. Once again, they were constantly harassed by Aurelian’s cavalry at short quarters, while Claudius’ main army shadowed them from a distance. The Goths tried to find another way north and out of devastated territory by turning east into Thrace, but there Aurelian and Claudius by skillful maneuvering managed to trap and surround them in the Haemus Mons (the Balkan range). By then it was already winter (269-270 CE) and cold, lack of provisions and the plague were not only tormenting the Goths (who were trapped in the cold mountains, without access to foodstuffs) but also the Roman forces, where discipline began to break down in some unclear its.

Suva Planina, in southeastern Serbia. This was probably the place where the battle of Naissus took place. Today is a nature reserve, and it's crossed by the remains of the Roman Via Militaris, which ran between Singidunum (modern Belgrade) and Byzantium.

In this situation, the Goths who were certainly weakened, but whose fighting spirit had been not broken yet) attempted a desperate break out attack against the Roman encirclement. Allegedly, Claudius ignored Aurelian’s advice and tried to block the Gothic sally only with the infantry, and the result was almost a total disaster for Roman arms; only the swift intervention of Aurelian’s cavalry against the Gothic flanks and rear avoided a complete Roman rout. Many Goths managed to break from the encirclement and divided into smaller warbands who began to roam the countryside of Lower Moesia and Thrace looting it for booty and food. By this time, plague was affecting severely the Roman army and even the emperor himself, and Claudius retreated to his regional headquarters at Sirmium to try to recover. The task of cleaning Thrace and Lower Moesia of Gothic war bands fell to Aurelian, who spend most of the spring and summer of 270 CE doing so.

This campaign marked a watershed in the military status between Rome and the Goths, for although it did not break the military power of the Gothic confederation and it did not put an end to the fighting between both foes, it helped to stop for a whole century further large-scale Gothic attacks into Roman territory (of the kind that had begun at the end of Philip the Arab’s reign). Together with the inactivity of the Sasanians in the East, this gave a much-needed balloon of oxygen to the Roman empire, because the two worse enemies of Rome during the III century CE were now (at least temporarily) out of the scene. This would be essential for the Roman recovery, because although many enemies remained, none of them were of the same caliber.

Apparently, after winning all these victories Claudius took the titles of Gothicus Maximus and Germanicus Maximus, although it’s unsure if he managed to go back to Rome to celebrate a triumph, because while Aurelian was wrapping up things in the eastern Balkans, the Vandals and Sarmatians broke across the Roman border in the middle Danube in Upper and Lower Pannonia. In late August or early September 270 CE, Claudius II died at Sirmium of the plague (probably one of the last outbreaks of the Plague of Cyprian), and nominated his brother Quintillus as successor, who was promptly acknowledged as the new augustus by the Roman Senate.

Claudius’ reign would set a trend until the accession of Diocletian: tough, soldierly and short-lived emperors who ruled from the saddle as they displayed superhuman energy running from one border to another fighting assorted invasions and usurpers. These Illyrian emperors managed to stabilize the military situation somewhat but failed at restoring a viable and stable political regime able to guarantee the internal peace needed to allow the recovery of many devastated areas of the empire; only Diocletian would be able to succeed in this regard.

Aureus of Quintillus. On the reverse, the (somewhat premature) legend FIDES EXERCITI (loyalty of the armies)

Quintillus controlled the small army left in Italy to control threats from Gaul, but the largest part of the army was gathered in Pannonia to fight against the Vandals, and it acclaimed the commander of Claudius’ cavalry, Aurelian as augustus. Upon hearing the news and realizing that Aurelian was supported by most of the army, Quintillus killed himself at Aquileia and left the field free for Aurelian. The choice is not surprising, because most of the merit for Claudius’ victories against the Goths in the Balkans belonged in fact to Aurelian’s skillful leadership, and the soldiers of the Illyrian and Danubian armies were well aware of this fact.

The new emperor has gone down in history as one of the greatest Roman generals ever (more than deservedly), although in my opinion even if he was without any doubt a stellar commander, he was not as successful as an emperor, because even if he was able to win an impressive amount of victories, he failed to address properly the political and fiscal crisis that had played a capital role in the downward spiral of the Roman empire.

Aureus of Aurelian. On the reverse, VIRTVS ILLIRICI, in praise of the martial qualities of the Illyrian army.

Aurelian’s reign began with the emperor having to deal with military trouble, and this would be the trend for the four years it lasted, with the energetic Aurelian rushing from one troubled spot to another, playing the role of the “imperial fire fighter“ (like Gallienus and Claudius II before him). His first task was to finish the fight in Pannonia against the Vandals and Sarmatians, a task that kept him busy for the remainder of the year 270 CE. One of the scarce surviving fragments of Dexippus’ Scythica describes how Aurelian resorted to a mix of military action and negotiations to close the campaign in Pannonia. Although it’s unclear if he could achieve a satisfactory result, because in the winter of 270-271 CE the Alamanni and Iuthungi launched yet another major invasion across the upper Danube, crossed the Alpine passes and invaded the northern Italian plain unopposed, moving at great speed and crossing the Po river. Aurelian had to hurry to Italy from Pannonia, but in January 271 CE the Alamanni defeated him near Placentia, and Aurelian was forced to retreat back towards the Julian Alps; it’s probable that the emperor had been surprised by the speedy advance of the invaders and had moved quickly to intercept them with only part of his army (perhaps only the most mobile units), and when he intercepted the Alamanni he found himself badly outnumbered and was forced to retreat and wait for the rest of the army to join him. The Alamanni seized the opportunity and advanced south along the Via Flaminia, with the clear intention of attacking Rome itself. When the news reached the Urbs, panic ensued, but luckily for its inhabitants, Aurelian reacted with energy and speed. He gathered his forces and pursued them; he caught them at Fanum (modern Fano, in Romagna) and there he defeated them in pitched battle, although the Alamanni were not routed and they were able to retreat northwards in good order and crossed again the Po river near Ticinum (modern Pavia). After the fiasco of Placentia and the danger of an attack against Rome, Aurelian’s reputation was at stake, and he pursued the Alamanni and Iuthungi into the northern Italian plain. He cut their path of retreat on an open plain near Pavia, and in the battle that ensued Aurelian routed the completely and recovered all the booty and captives that his foes had plundered during their invasion. Only a small group was able to cross the Alps back into Raetia, but even this small force was pursued and destroyed by Aurelian. After this victory, Aurelian assumed the title Germanicus Maximus.

The city of Rome had suffered its second major invasion scare in a decade, and in a political gesture aimed at inspiring confidence to its inhabitants, Aurelian ordered the building of a new wall around the city, the first one to be built in Rome since the times of the legendary king of Rome Servius Tullius. The wall was a propaganda gesture more than anything, because its disproportionate length, the huge population of Rome and the lack of reliable water springs within the city meant that the city was indefensible against a serious enemy, but it would serve to stop isolated “barbarian” war bands from plundering the city, giving time for relief army to be sent by the emperor.

Aerial view of the Aurelian Wall in Rome; large tracts of it are still intact.

This decision was probably prompted by the unrest that beset Rome in the aftermath of the invasion scare. In the summer of 271 CE, the workers of the Roman mint revolted, and this soon translated into widespread riots across the city. Some scholars link this revolt to the decision by Aurelian to reform the currency, which had reached its absolute nadir during the early 270s CE. Part of the reform included the decentralization of minting from big mints as the one in Rome into smaller ones closer to the borders (where the soldiers had to receive their pay), like Siscia in Illyricum (modern Sisak, in Croatia). And the guild of minters seems to have taken the news quite badly, the rioting lasted several days and led to thousands of deaths in the fighting. The SHA’s account tells us that Aurelian had the revolt put down by the sword, killing thousands in the process, and killing also a large part of the city’s leadership (i.e. the senators); this is just another example of the SHA’s view of Aurelian as a brutish, bloodthirsty tyrant, which finds an echo in other Latin sources, especially in Ammianus Marcellinus, with his quote that Aurelian “fell upon the rich like a torrent”. From these examples it’s clear that the senatorial tradition was quite hostile towards Aurelian, but Zosimus presents a much milder view of Aurelian, reflecting probably the opinion of (now lost) III century CE Greek sources. In his efforts to pacify the Urbs before departing for the East, apart from ordering the building of the Aurelian Wall, he ordered that from that on the food dole to the Roman populace would also include pork, apart from bread and olive oil (all at the state’s expense).

But Aurelian had no time to rest on his laurels, because alarming news arrived from the Balkans and the East. In the Balkans, the Goths had attacked Dacia and the lower Danube once again, and Aurelian moved quickly against them in early 272 CE, winning his third campaign in less than two years. After this victory, he took the name Gothicus Maximus and took a drastic decision regarding to the defense of the Danubian border: he ordered the abandonment of Dacia and the evacuation of all the military and civilian personnel, as well as any civilians who wanted to remain under Roman rule. This was an extraordinarily risky decision for any Roman emperor to take, because abandoning conquered territory was anathema in Roman political culture, especially a territory that had been Roman for more than a century and a half, but there was already the recent precedent of the Agri Decumates, and from a strategic point of view the decision made sense for a beleaguered empire that had been fighting desperately on the defensive for decades. It shortened drastically the border to defend, abandoning a very exposed territory that anyway was scarcely populated and Romanized and had to be defended with a large garrison of two complete legions and more than 10,000 auxiliaries. Pulled back behind the Danube, these forces would have to defend now a drastically shortened border.

This second Balkan campaign though was just a minor affair for Aurelian, because the major reason for his presence in the Balkans was that he was moving with his army to the East, where the political situation had reached a breaking point between Rome and Palmyra.

Last edited: