Unless stated otherwise, sources in this list are from the book "Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States", which has been an invaluable resource for this task. The document is split into 5 volumes, which can be found as PDFs on the Myanmar Law Library

https://myanmar-law-library.org/law-library/legal-journal/burma-gazetter/ (note that there are some occasional scan errors which might make some letters appear wrong, e.g. "Küng" becoming "Kilng")

For names I've transliterated directly from the Shan script, or names I've adjusted the spelling of, I've followed the document "Tables for the transliteration of Shan names into English (1892)" (Z library link

https://z-lib.io/book/16791705). However, I've avoided using hyphens and long-vowel-diacritics (ā, ī, ū, ē), these are almost never used in maps or articles so it would just make everything inconsistent. Anyway, this isn't the only method which is used for transliterating Shan, but it's the closest to the names you'll see in maps, articles, the Burma Gazetteer, etc. The Shan script has also added some characters since 1900, in which case you can fill in the gaps from Omniglot's table

https://www.omniglot.com/writing/shan.htm

In regards to the above, most of those transliterated names are from Shan Wikipedia. The names on Shan Wikipedia are mostly from Shan news agencies or Shan revival projects, so it's probably a very reliable source.

On to the actual list - names will be given first in Shan, then have the Burmese name in brackets, then any other local names in the notes afterwards:

Kachin area

Hkamti province

1. Hkamyang - Named after the Tai Khamyang people who lived here at the time, the Ahom chronicle also mentions it as a place name.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khamyang_people If not this, it could also be named Nawng Yang (Shan name for the Lake of No Return), Man Nam (supposedly an old Khamyang village by the same lake), or Pang Sao (Pangsau, modern town, founded 1775)

2. Hpake - New location, split from Hkamyang (Tarung) to represent the stark difference between the valley and mountains in the original location, and the fact that the route going west to the Hkamti location goes directly from one valley to another. Named after the Tai Phake people who lived here at the time. "Phake" refers to a river gorge in the Hukawng valley, probably near modern Shin Bway Yang

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Tai-Phake_people_in_northeast_India Interestingly, this old map also marks Phake-yooa in the same place

https://www.geographicus.com/P/AntiqueMap/burmanempire-wyld-1879 If not this, then the only other name would be Hukawng (Payindwin in Burmese) which was an ancient province of Möng Kawng

3. Möng Hkawn (Maingkwan or Maingkhwan) - Given as the Shan name of Maingkwan, there are some spelling variations like Möng Hkwan or Möng Kawn

4. Tanai - This was originally Maingkwan on your map, but that would've been the wrong place. This location just seems to be the upper reaches of the Tanai river, there aren't any major settlements even today and I'm a skeptical if it should even be a location

5. Hkamti (Kanti) - Moved the border southwards a little to balance out my other changes. This town is also called Singkaling Hkamti to distinguish it from the original Hkamti (Hkamti Long), it was settled by Shans in the 18th century and Singkaling was apparently the name of the Naga tribe who lived here before

6. Tamansai (Tamanthi or Htamanthi) - Minsin was a tiny village (I'm guessing this is a leftover from EU4) so I moved your original Htamanthi up here and gave it a connection with Tizu (important because the river connection leads directly into the town). The Shan name is Tamansai

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2843177

Htamanthi province

I've represented the rough location of the Ungoching hill range in black, this is an uninhabited stretch of land with only a few places you can pass through, so you might want to represent it.

7. Hongmalang (Homalin) - Shan name is Hongmalang (Upper Chindwin Gazetteer, page 75

https://www.myanmar-law-library.org...azetter/upper-chindwin-district-volume-a.html)

8. Hpakan - Spelling changed from Phakant. This town likely didn't exist more than 200 years ago, but I couldn't find a better name

9. Möng Küng (Maingkaing) - Also called Möng Köng or possibly Möng Küng Kwai in the Hsenwi chronicle

10. Hsawnghsup (Thaungdut) - New location, split from Hkampat (Tamu) for political borders. The modern town of Hsawnghsup is located on the Chindwin river, but the old town was located in the north of the Kabaw valley, near modern Thanan or Myo Thit, it moved to the current location around the 1800s

11. Hkampat - Also called Khampat. At the time, it was a bigger town than Tamu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabaw_Valley

12. Hpawngpang (Paungbyin) - Transliterated from Shan Wikipedia ၽွင်းပၢင်ႇ

13. Mawlek (Mawlaik) - New location, split from Hpawngpang (Paungbyin) to balance the size with neighbouring locations. I also extended the border a bit further west to fit the geography. "Mawlek" is transliterated from Shan Wikipedia မေႃႇလဵၵ်

Kale province

14. Kat Lü (Kale) - Transliterated from Shan Wikipedia ၵၢတ်ႇလိုဝ်း

15. Kalewa - New location, split from Kale to represent the hill range and balance out Kale's size. Names are identical in Shan (ၵလေးဝ) and Burmese. I'm not really happy with the name of this location, Kalewa seems like it might be a new settlement or name, some other options could be Masein or Singaung, but I couldn't find Shan names for these, at best it would just be guesswork changing Singaung to Sinkawng.

16. Möng Kang (Mingin) - I extended the border of this location north to make it look better and to fit traditional state boundaries. Name transliterated from Shan Wikipedia မိူင်းၵၢင်း

Wuntho province

17. Man Mawk (Banmauk) - New location, split from Möng Küng (Zalon Taung) and parts of Katha and Htigyaing to represent the surrounding hills and valleys better. Name transliterated from Shan Wikipedia မၢၼ်ႈမွၵ်ႇ

18. Kat Hsa (Katha) - Transliterated from Shan Wikipedia ၵၢတ်ႇသႃႇ

19. Tikang (Tigyaing or Htigyaing) - Transliterated from Shan wikipedia တီႈၶင်ႉ

20. Pangkaihpo (Pinlebu) - New location, split from Waing Hsö to represent the surrounding hills and to reduce its size. I've also given it a connection through the wasteland to Hpawngpang (Paungbyin). "Pang Kai Hpo" is given as the Shan name, but I removed the spaces

21. Waing Hsö (Wuntho) - Waing Hsö is given as the Shan name

Möng Kawng province

22. Möng Kawng (Mogaung) - Added a space

23. Möng Yang (Mohnyin) - The given Shan name. Also, in your original map Mohnyin has a typo

24. Sanakawng - Myitkyina wasn't called that until British rule. Jingpo oral tradition says the area used to be called Sana Kawng (this article is written in Jingpo but the language is supported on Google Translate now:

https://researchdata.edu.au/kk2-0267-myitkyina-history-myitkyina/1601073) or Tsaya Kung (

https://www.kachinlandnews.com/?p=28020). I went with Sanakawng (or just "Sana") because Shan Wikipedia still calls Myitkyina "ၸႄႈၼႃး" (Sana/Sena), and some Chinese sites call it Sinagong

25. Hsanghpo (Sinbo or Hsinbo) - New location, split from Möng Set and a small part of Möng Kawng to represent the surrounding hills. It might not be a great candidate because Sinbo was founded in the 18th century. Shan name transliterated from Shan Wikipedia သၢင်ႇၽူဝ်ႇ

26. Möng Set (Mosit) - The original name of this location (Möngyang) was just a clone of the neighbouring location, probably a leftover from EU4 which had it in the wrong place. Möng Set is mentioned under the Shwegu section of the Upper Burma Gazetteer

Putao province

27. Putao - The Shan name (ပူႇတႂ်း) is still Putao, although its mentioned that old name might have been "Putaung" or "Putawng" (since our Shan transliteration doesn't use "au"). The Jingpo name of the valley here is apparently "Gam Di" (from book "Institution of Kachin Duwaship")

28. Nam Kiu - Changed from Suamprabum, which was founded by the British. I couldn't really find any other settlements so I just named it after the river, Mali Hka in Jingpo or Nam Kiu in Shan (Nam Kiu is also the Shan name for the entire Irrawaddy)

29. Möng Tong - Changed from Injangyang, which was also founded by the British, or just before they came. There's a single paper (

https://meral.edu.mm/records/2465) which says Injangyang used to be called Mong Tong, but I'm not sure how reliable it is. The Jingpo name for this region is "Hkahku"

30. Nam Tamai - Changed from Chibwe, which seems like a new town too. It's the name of a river again because I couldn't find anything, the river is called Nmai Hka in Jingpo and Nam Tamai in Shan

https://www.himalayanclub.org/hj/11/6/ka-karpo-razi-burmas-highest-peak/

31. Waing Maw - Space added

Shan Highland area

Manmaw province

32. Möng Lai (Mole) - New location, split from Man Maw because it felt too big compared to its Yunnan neighbours. The name is based on the Mole Chaung (river) which flows from modern Laiza to its mouth a few miles north of Bhamo. Möng Lai is only given as the Jingpo name, and Menglai as the Chinese, but it's very obviously a Shan-origin name.

https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-cn/穆雷江 The Mong Mit chronicle mentions a settlement called "Molai", which could very possibly be referring to an ancient town which the river got its name from.

33. Man Maw (Bhamo) - Space added

34. Möng Leng (Mohlaing) - New location, split from Shwegu because a hill range separates the two areas and because Möng Leng later became an independent state for some time. Möng Leng was located in the Sinkan Chaung river valley

35. Hweku (Shwegu) - Transliterated from Shan Wikipedia ႁူၺ်ႈၵူႈ

36. Man Peng (Mabein) - Transliterated from Shan Wikipedia မၢၼ်ႈပဵင်း

37. Namhkam - unchanged

38. Möng Mit (Momeik) - added a space

Hsipaw province

39. Möng Long - spelling change

40. Hsum Hsai (Thonze) - Changed from Kyaukme, which didn't exist at the time. Hsum Hsai was an important town and sub-state of Hsipaw

41. Ongpawng (Onbaung) - Also known as Hsipaw (Thibaw) which was nearby. Hsipaw seems to have been either non-existent or very small before ~1600s, so Ongpawng would be the more correct form for 1337.

42. Möng Tung (Maington) - New location, split from Hsipaw because of the geography and because Möng Tung was an important town and sub-state of Hsipaw.

Hsenwi province

43. Namhsan - Unchanged. Also known as Om-yar in Palaung.

44. Möng Yin - New location, split from Hsenwi. I only really added it because I thought Hsenwi looked too big, but Möng Yin was also apparently a sub-state of Hsenwi.

45. Hsenwi (Theinni) - Unchanged

46. Möng Yaw - Changed from Lashio, which was either a tiny village or didn't exist before the 1800s.

47. Muse - Unchanged

48. Möng Si - New location, split from Muse because it was huge compared to some of its surroundings.

49. Tawnio - Also known as Taw Nio or Malipa. This name doesn't seem to exist on maps today, but it would've been in the same place as modern Laukkaing.

50. Möng Kun - Given as a Shan village in the Son Mu state. The location could also be called Möng Hit, another village

Monghsu province

51. Man Se - New location, split from Möng Yai and a small part of Lashio. I thought it made sense to add because of the geography and to reduce the size of Möng Yai. Man Se was an important village located near modern Nampawng

52. Tangyan - Split from Möng Yai because of the large hill tract splitting them apart, and because it became a sub-state separated from Möng Yai. Called "Tang Yan" in the Gazetteer

53. Möng Yai - Spelling change

54. Kehsi (Kyithi) - Technically called Kehsi Mansan (Kyithi Bansan)

55. Möng Hsu - Spelling change

56. Möng Nawng (Maingnaung) - Added a space

57. Keng Hkam (Kyaing Hkan) - Spelling change

Mongpai province

I rearranged the locations in this province and added 2 new ones, trying to separate them based on the different valleys in this region:

58. Lawksawk (Yatsauk) - Northern valley, Lawksawk is technically not in the northern valley but there wasn't a better name since Lawksawk always controlled that valley

59. Hsamönghkam (Thamaingkan or Thamakan) - The western valley and highlands, I also extended it a little further westwards into the wasteland and Pinle location since the valley extends further this way (e.g around modern Ywangan). There were a lot of small states and towns in this region, but Hsa Möng Hkam seems to be the oldest.

60. Yawnghwe (Nyaungshwe or Nyaungywa) - The central valley around Inle Lake. Taunggyi didn't exist before British rule, so that was removed.

61. Möng Ping (Maingpyin) - Some small valleys and their surrounding hills, north to modern Möng Lang and south to modern Hopong. This could also probably be called "Möng Pying" to avoid confusion with the other Möng Ping

62. Nawngwawn (Naungwun or Naungmon) - Eastern valley, Nawng Wawn seems to be the oldest important settlement

63. Möng Pai (Mobye) - Southern valley, not really changed from its original location, I just moved the border slightly further northwest

Mongnai province

64. Möng Küng (Maingkaing) - Added a space

65. Laihka (Legya) - Removed the space

66. Keng Tawng (Kyaingtaung) - Extended the border slightly further east into Möng Ton, this area was traditionally owned by the Keng Tawng sub-state (and looks better)

67. Möng Nai (Mone) - Spelling change

68. Mawkmai (Maukme) - Unchanged

69. Möng Pan (Maing Pan) - New location, split from Möng Ton and Mawkmai. The southern portion of this new location wasn't part of Mawkmai until the 1800s, so it's not necessary to include that as part of Mawkmai location

70. Möng Ton - Spelling change

Kengtung province

71. Möng Pu - New location, split from Möng Ping to reduce its size

72. Möng Ping - Spelling adjusted. Border extended into the northern portion of Keng Tung, this area is mountainous and completely cut off from Keng Tung so it makes more sense to go to Möng Ping

73. Möng Yang - Spelling adjusted

74. Keng Tung (Kyaingtong) - Name given a space. Border extended into the southern portion of Möng Yang, the mountains cut off this area from the rest of Möng Yang.

75. Möng Hsat - Unchanged

76. Möng Hpayak - Spelling adjusted

77. Möng Yawng - Spelling adjusted

Yunnan area

I haven't added any new locations in China because I think the density was fine (with the exception of Menglian province, which is partly in Myanmar and had large locations). I couldn't find names for some locations, if any Chinese speakers can help find Dai origin names then I could be able to help with translating them.

A lot of names here are still from the Upper Burma Gazetteer, so the same rule applies about that being the primary reference unless stated otherwise. Some names are transliterated directly from the Tai Nüa script

https://www.omniglot.com/writing/dehongdai.htm, for which I've slightly adjusted a few letters based on the IPA to have them line up better with spellings from the Burma Gazetteer and main Shan State.

A list of place names with their Chinese counterparts can be found here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mueang and here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koshanpye

I'll give those Chinese counterparts in brackets below.

Tengchong province

78. Santa (Zhanda)

79. Möng La (Yingjiang) - Can also be spelled Möng Na

80. Möng Myen (Tengchong) - Called Momien in Burmese.

81. Möng Ti (Lianghe)

Mangshi province

82. Möng Wan (Longchuan)

83. Möng Mao (Mengmao/Ruili)

84. Möng Hkawn (Mangshi) - Can also be spelled Möng Hkwan or Möng Kawn

Yongchang province

85. Möng Hkö (Lujiang) - Transliterated from ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ᥑᥫᥰ

86. Möng Sang (Yongchang/Baoshan) - Technically called "Meng Sang" in the Upper Burma Gazetteer, but I think "Meng" is very obviously just a Chinese reading of Möng. The Upper Burma Gazetteer also calls it Wan Chang in other places

87. Möng Long (Longling) - Can also be spelled Möng Lung

88. Möng Mo (Jiucheng) - Transliterated from ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ᥑᥫᥰ

89. Möng Hkeng (Zhenkang) - This one is only mentioned in the Upper Burma Gazetteer, where the Chinese name is spelt Chen Kang

Shunning province

90. Möng Htong (Changning) - Transliterated from ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ᥗᥨᥒᥴ

91. Möng Hten (Fengqing) - Transliterated from ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ᥗᥦᥢᥴ

Mengding province

92. Möng Ting (Mengding)

93. Möng Tum (Mengdong) - Transliterated from ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ᥖᥧᥛᥰ

94. Möng Möng (Mengmeng)

95. Möng Myen (Lincang) - Could also be spelled Möng Men

Menglian province

I have added 2 locations in this province on the modern Burmese side

(Burma side)

96. Man Hpang - New location, split from Pangyang because the original location was huge compared to its neighbours, and to represent the borders of the Mot Hai sub-state. Man Hpang was given as the capital city of Mot Hai

97. Pangyang - Border slightly extended eastwards

98. Man Pan - Renamed from Matman. Man Pan was given as the capital of the Maw Hpa sub-state

99. Panghseng - New location, split from Man Pan to reduce the size and to represent the borders of the Maw Hpa sub-state. The name is given as "Pang Hseng" in the Upper Burma Gazetteer, but I removed the space

(Chinese side)

100. Möng Ka (Mengka) - A Tai script name isn't actually given for this, but we can assume that Meng = Möng

101. Möng Lem (Menglian)

102. Möng Lam (Lancang) - Transliterated from ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ᥘᥣᥛᥰ

103. Möng Ngüm (Shangyun) - Transliterated from ᥛᥫᥒᥰ ᥒᥤᥛᥰ

Weiyuan province

104. Möng Ban (Mengban) - A Tai script name isn't given for this, again we can assume that Meng = Möng

Simao province

A lot of names below this point are from the book "Burmese Sources for Lan Na Thai history", where I've tried to place their names based on a map of Sipsongpanna (

map). Unless stated otherwise, this is the source for all names below.

105. Möng La (Simao)

106. Keng Tong (Chiang Tong on the Map) - Could also just be named Möng Lie based on the original name (Menglie)

Cheli province

107. Keng Law (Chiang Lo on the linked map) - The Upper Burma Gazetteer also mentions Keng Law on the border with Mong La (In Burma, not any of the other Mong La's)

108. Möng Hai (Menghai)

109. Keng Hung (Jinghong) - also in Upper Burma Gazetteer

110. Möng Hing (Meng Hing on the map)

111. Möng Pang (Mengban) - I'm not 100% sure about this one, but it seems right

112. Möng La (Mengla) - This name is identical to Simao Möng La except for the tone marker, another name for this location could be "Möng Hpong" (Mengpeng) which is mentioned in the Upper Burma Gazetteer

113. Möng Hu No (Meng U-Nua on map) - Currently Yot Ou in-game. This could probably also just be called "Möng Hu", since I think the "No" is only there to distinguish it from "Möng Hu Haii" which is a few miles away

Quite a variation of resources, although dominated mainly by lumber and rice.

Quite a variation of resources, although dominated mainly by lumber and rice.

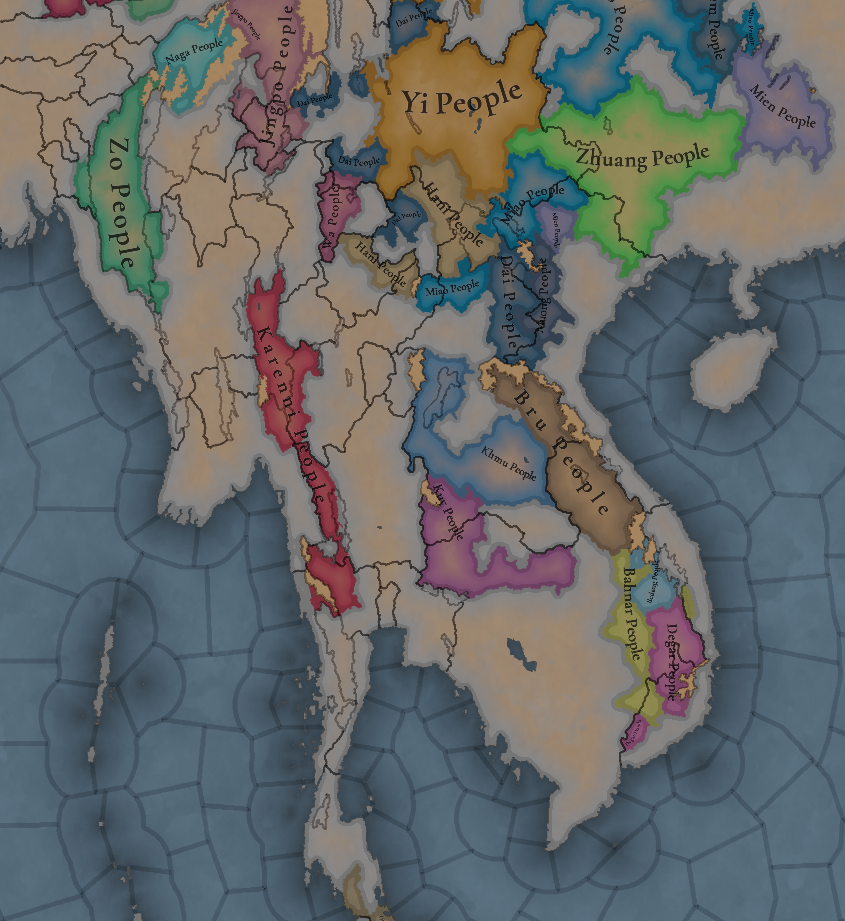

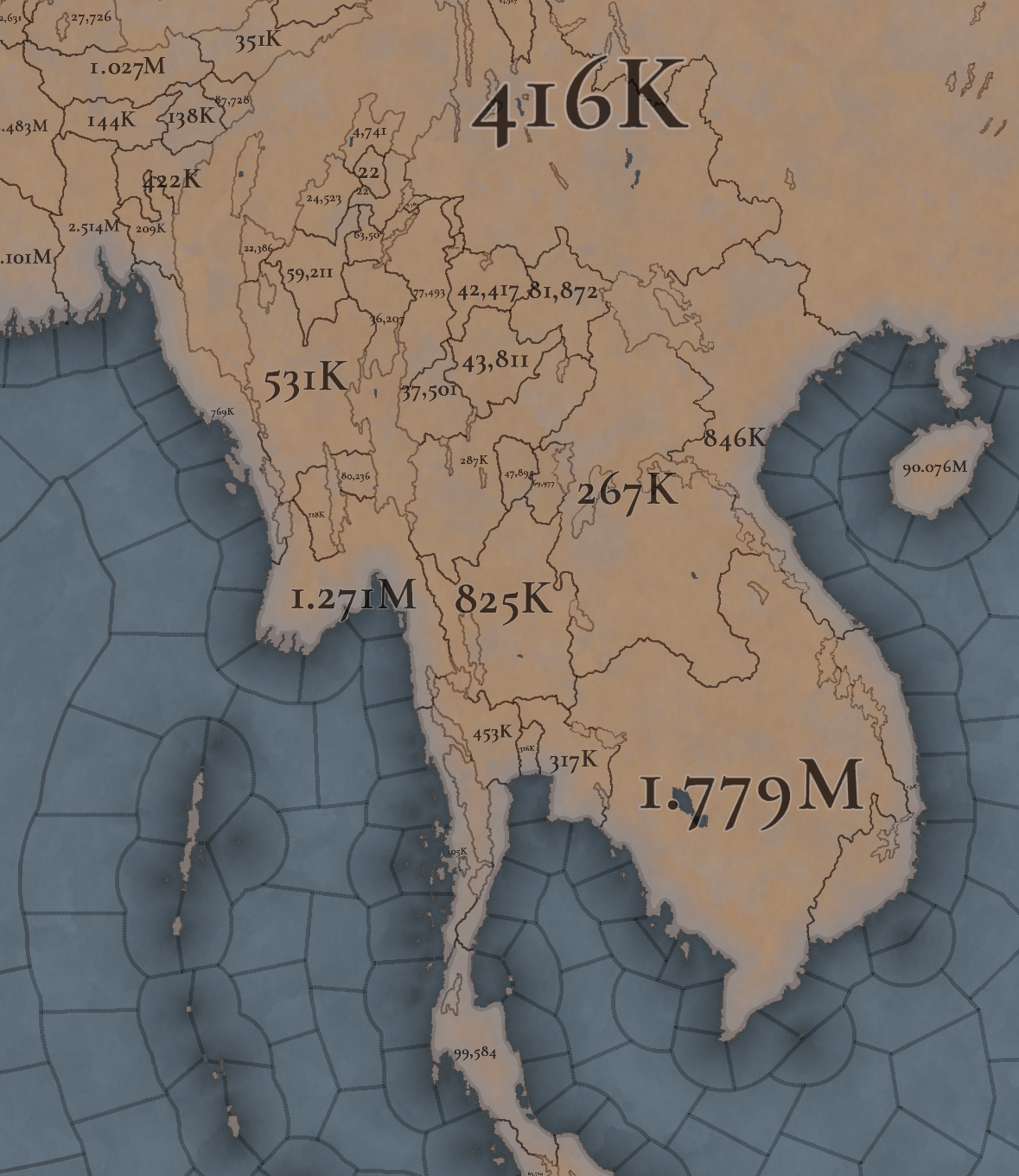

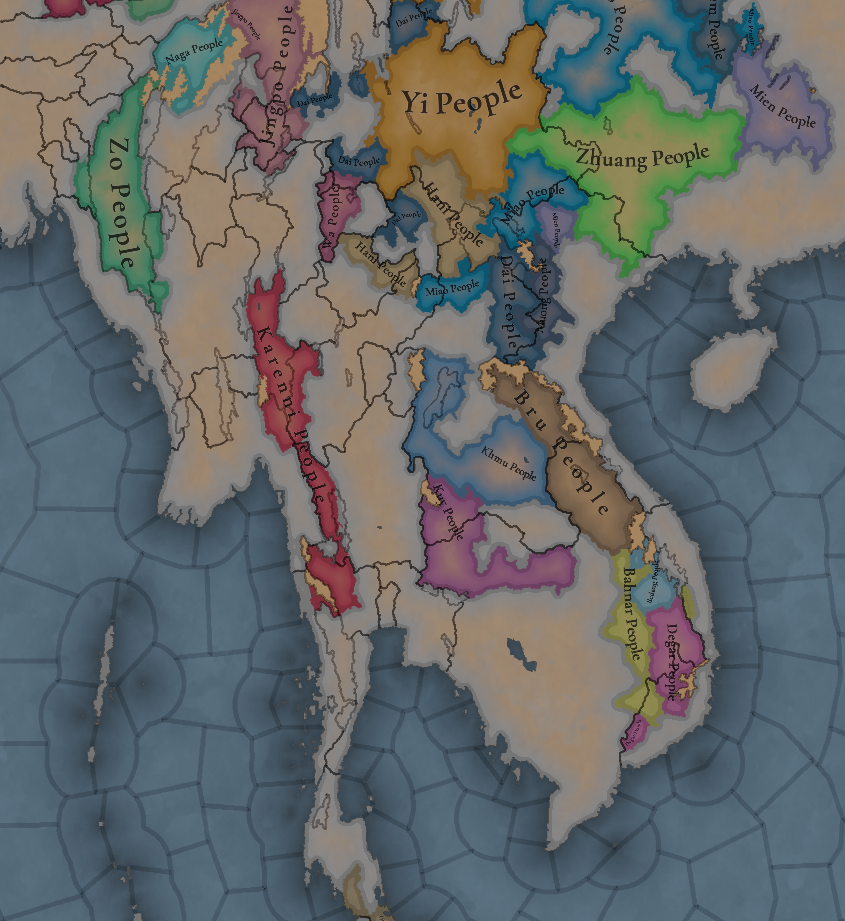

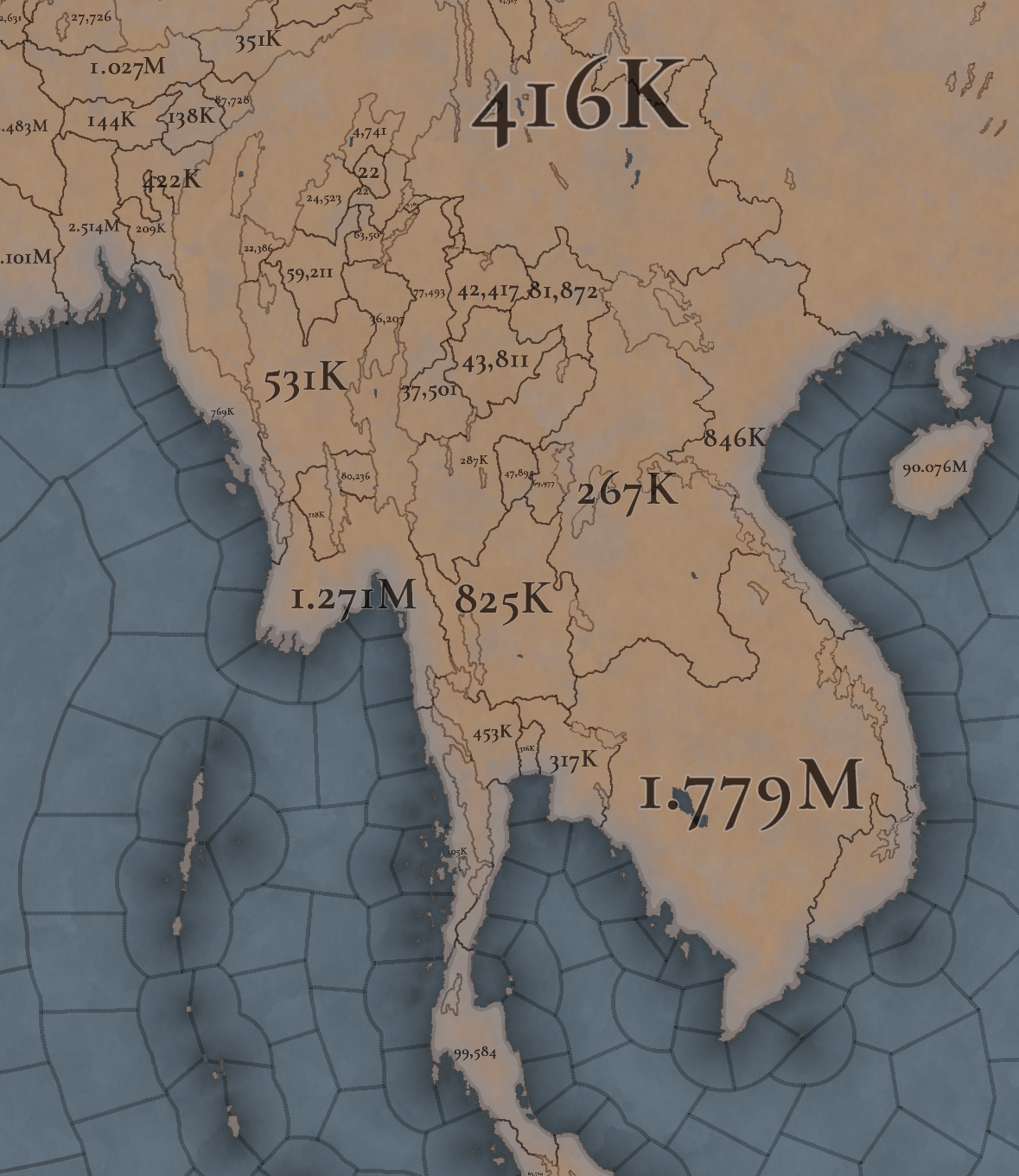

Khmer is still the most populated, but other countries around don’t fall that far behind, especially when they manage to unify their areas a bit. There’s also a couple of locations appearing as 0 population that is definitely a bug that will have to be fixed.

Khmer is still the most populated, but other countries around don’t fall that far behind, especially when they manage to unify their areas a bit. There’s also a couple of locations appearing as 0 population that is definitely a bug that will have to be fixed.