With the death of Vizier Malik Abaya, Assyria was shorn of the man who had dominated every part of its body politic for nigh on three decades. With no clear successor or even especially influential deputies, there was an immediate scramble for power and position. The biggest question was whether a military figure would follow in Abaya's footsteps and use brute force to establish control over the state. As such, the deputies in the Majlis attempted to move with speed and unanimity to exert their own authority before any putschist threat could materialise. The unlikely figure of the secretarial Baghdadi Jew Samuel Bellilios, who had served Abaya for many years as a key fixer within the Majlis, who was able to rally the Moderate coalition around himself within a matter of a few days. Alongside the usual offers of bribes, influence and position, Bellilios importantly swore to serve only in a temporary capacity, and seek to transition away from a period of personal rule towards a parliamentary regime in which the Majlis would be dominant. This gambit was a success. As Bellilios was elevated to become Vizier, the fear military coup did not materialise and a smooth, bloodless, transition of power was won.

With a generation having passed since the Revolution, traditions of veneration had started to develop. One expression of this was popular celebrations around anniversaries of important events – the largest of which developed on 'Republic Day', April 2, celebrating the date at which the Federal Republic was proclaimed. Reminiscent of Saints' cults, key individuals achieved elevated status – notably Lazarus Dunanu, the martyred leader of Assyrian liberalism in the 1730s and a break on Ishtarian radicalism in the 1740s who was eventually claimed by the Terror. A large statue of Dunanu was constructed on the site of his execution during the 1760s, and would become a focal point for Republic Day celebrations.

Most impressive of all was a grand Mausoleum of the Republic constructed in the centre of Nineveh, which featured thousands of individual graves from martyrs of the Civil War and Great Persian War. Still under construction at the time of Abaya's death, it would later be amended to include a large complex at its centre in which the remains of the fallen Vizier Malik Abaya were entombed in ornate and imposing opulence. This tomb would be a site of veneration and pilgrimage for generations to come.

Despite the veneration of the great man, Bellilios had captured a prevailing mood among national elites in his turn away from personal rule. This ideal was best captured in the monumental work of political philosophy 'The Spirit of the Laws', which was published two years after Abaya's death. Its author, Addai Abdima, had been born in the Syriac community of the Jordan Valley at the beginning of the century and had served as a Federalist and later Moderate representative in the Majlis at various points during the 1740s and 1750s and later as a governor in his native Philistia before retiring to a life as a philosopher of government. Waiting until after the death of the great man to publish his magnum opus, he had nonetheless spent years advocating for strict constitutionalism and the division of power. The publication of his greatest work had been deliberately delayed in an effort to avoid it appearing as an attack on Abaya, yet it was clearly written with the desire to prevent any future leader from centralising so much power in their hands. The text called for the separation of powers between the executive, legislative and legal branches of government, and their binding together by harsh adherence to a clear and detailed constitution. His work would strike a cord with among the Assyrian political elite, and Bellilios, who had known him personally for many years, would call upon him to help to draft a new constitution.

True to his word, just three years after taking office Bellilios retired as Vizier and turned over to the Majlis to consider his successor ahead of the first set of elections of the post-Abaya age. That man who would step up to become Vizier and take leadership of the Moderate faction was, it an incredible statement of the Republican era, a Sunni Muslim raised as a pauper. Abgar Israel hailed from Muslim Upper Egypt, a land that had only recently been annexed by Assyria prior to the Revolution. Israel was an orphan, who grew up as a street child in Assyut on the banks of the Nile. As a young man in the 1740s, he saw his homeland occupied by the reactionary Catholic 'King of Egypt and Jerusalem' during the Assyrian Civil War, with the Christian occupiers inflicting horrors on the Muslims of Upper Egypt. During this time he joined a gang of bandits that would harass the occupiers and live on plunder.

As the Civil War drew towards an end, and Malik Abaya led his armies into Egypt – Israel's gang declared themselves Republicans and supported the invasion. In post-Civil War Upper Egypt, his loyalist status allowed him to enter the local administration. Completely illiterate as a youth, he not only taught himself to read and write as an adult, but learned numerous languages – Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Greek – and developed a diversity of intellectual interests. Better yet, he was an exceptional political organiser – turning Upper Egypt into an effective Moderate-controlled one party state – and competent administrato

Coming to Nineveh as a Majlis representative in 1766, he was a part of numerous governments and build up a wide network of allies throughout the assembly. At Bellilios' resignation, pulling in every favour, he secured the Majlis' support to become Vizier. For a nation in many ways founded in opposition to a then Islamic dominated Middle East in the Medieval period, and often defined in its struggles against the Muslims, to see a Sunni orphan take up the Republic's highest office was extraordinary.

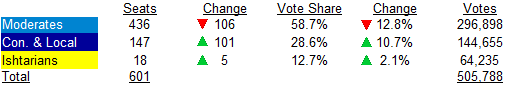

The new elections, seeking to confirm the post-Abaya administration, produced results that shook Nineveh. The near monopolistic Moderate control over the Majlis was ended, as the Moderates secured their worst result since the formation of the faction after the 1748 coup d’etat. While the Moderates still held on to a large majority in the Majlis and the popular vote, they shed more than a hundred seat in a contest that saw dozens of long serving representatives unseated. The beneficiaries of this decline were a scattered array of conservative and localist candidates sitting to the right of the government. The success of such candidates, who won more than a quarter of votes nationwide, was a great shock to the Republican elites in Nineveh. But it was a turn that had been building for years.

Even before the death of Abaya, the rumblings of a revival in traditionalist sentiment could already be heard around Assyria. In 1774, a small group of Old Nestorian lay people from poor communities in the swamps of the Shatt-al-Arab in southern Babylonia conducted a march from Basra to Nineveh, carrying on their backs large wooden crosses. During their long and tortuous journey, during which they faced harassment from government authorities and bandits alike, they cried out lamentations for the exile of their Patriarch in India and the eclipse of God in His homeland. Each year, the march was repeated, grew larger and more organised. By the end of the 1770s many thousands were taking part, in 1780 presenting a petition to the Majlis listing 500,000 names calling for the exiled Patriarch to be allowed to return to his seat in Nineveh. This was the first display on mass religiosity on such a scale for decades and spoke to rising spiritual unease.

In India, the Patriarch made a deliberate attempt to cultivate strong ties with the St Thomas Christians, or Nasranis, of Malabar. While the majority of Nasranis lived under Assyria rule, a substantial minority resided around Calicut, just to the north of Assyrian Malabar, and there the Patriarch made numerous visits – preaching to huge crowds and attracting many Christians from across the border in Assyrian territory. The Indian Christians, always comparatively conservative, rejected the New Nestorian Church in Nineveh outright and would provide significant financial and material backing to sustain the exiled Patriarchate, and aiding its connections throughout the Assyrian world.

Alongside this religious backlash, there were important dynastic changed among the exiled monarchist claimants to the vacant Assyrian throne. Nahir III, the last standing Lebarian claimant of the Civil War who had fled to the Cape after the fall of Basra before in turn being overthrown in 1753, had spent decades in exile in Europe fruitlessly seeking military support to bring down the Republic before dying in 1773. He was survived only by one daughter, Fariah. After living for some years in Sweden, she travelled to France in 1777, where she came into contact with the grandson of Niv IV, one Yeshua III. The two distant cousins agreed to wed, thereby mending a near-century old divide within the Assyrian imperial dynasty.

In the Federal Republic, this marriage was important as it allowed monarchists to rally around a single claimant that all could agree on. Furthermore, the Lebarian cause, always popular in the conservative Nestorian heartlands of Babylonia and the Gulf, had long carried baggage that limited its appeal outside of this core territory while also lacking the same international legitimacy that the heirs of Niv IV, the recognised legal sovereign, held. Although forbidden by law to forge formal organisations, secret monarchist clubs, often little more than drinking and social societies to begin with, had been proliferating widely through the 1770s – gaining traction not only in the south east, but through Old Nestorian communities in Assyria-Superior, one of the heartlands of the Revolution, and in Philistia among both the Nestorians of the Jordan Valley and Catholics of the coastal plain.

The new constitution, the work of the ageing philosopher Abdima, would be enacted in 1780. The Vizier's role would be made quite distinctive, to be elected by a majority vote of the Majlis but thereafter be independent of it as the executive arm of government, while the Majlis itself would operate at the legislative branch. Elections to the Majlis would be held every three years under the existing franchise, at the beginning of each new session of the Majlis the assembly would be tasked with either electing or re-electing the Vizier. The courts were to be completely independent and powerful, with the authority to enforce the constitution. The provinces of the Republic, now styled as states, were given clear authority over local affairs, but placed within limits relative to the Federal government in Nineveh. In an anti-militarist diktat, serving members of the army and navy were forbidden from serving in any other capacity in the state without special dispensation from the Vizier.

The most important change of all was a geopolitical decision – the integration of the Republic of Damietta into the Assyrian Federal Republic, thereby ending centuries of autonomy for Lower Egypt's Copts. Many in Assyria had held ambitions of bringing Damietta into the Republic for years, but had relented from doing. Culturally distinct from the Arabic Muslim south, northern Egypt was home to millions of Coptic-speaking Catholics with a Latin-speaking elite and a speckling of religious and ethnic minorities. For centuries they had tended to look westward to Europe rather than eastward to the Middle East, and many were very hostile to greater Assyrian control. The region's demographic heft relative to the rest of Assyria had only grown during the harsh years of War and Revolution in Mesopotamia and the Levant. At unification, Lower Egypt contained around a quarter of Federal Republic's metropolitan population. For the Vizier, himself an Egyptian from the Muslim south, its integration was a statement of personal ambition and a belief in the universal values of the Republic.

For a time in the middle of the eighteenth century, it appeared that the revolutionary force of republican liberalism unleashed in Assyria was going to take over the entire world. At their peak, an unbroken belt of Republics controlled all the lands between the Persian Gulf and the North and Baltic Seas while sympathetic constitutional monarchies held sway in Italy and the mighty Timurid Empire.

However, the conservative wave that was impacting Assyrian politics domestically was a part of an international phenomenon of reaction. To the east, the liberal Persians had been faced by incessant rebellion and civil war ever since the end of the Great Persian War, and the Khan had slowly backslid on the constitution he had granted his subjects at the end of the war. In the west, the Croatian Republic was blighted by persistent instability and rebellions, particularly in the Danubian territories it had acquired from the Byzantines during the Revolutionary Wars, with reactionary and regional nationalist sentiment leaving the state always on the brink of collapse. The German Republic was more sturdy, although numerous border conflicts with the French, supported by Scotland, meant that it was never able to settle into a prolonged period of peace.

In the Roman Republic, things were far worse. The Byzantium that emerged from the Revolutionary Wars was a humbled and divided one. Having lost significant territory, endured terrible loss of life and economic dislocation, international humiliation and the distress of the end of nearly two millennia of monarchy, the country was something of a basket case. While the revolutionaries who had seized power in 1751, with the Assyrian army baring down on Constantinople, had some popular support in the cities, they were largely despised in the hinterland provinces which remained steadfastly loyal to the monarchy. In the second half of the 1770s, this fragile Republic would collapse.

The trigger for the downfall of the Second Roman Republic came from the unlikely source – the ending of enmities between Byzantium and Assyria. Central Anatolia was a sparse territory mostly populated by the Turkic Cumans. Much like their cousins in the Middle East, the Anatolian Cumans were a warlike people, for centuries they had upheld traditions of raiding across the border into Assyrian Armenia, usually with the active encouragement of Greek authorities that were happy to direct their energies eastward. With the establishment of peace between Constantinople and Nineveh, the Assyrians put pressure on their new friends to end these raids permanently. The Byzantines attempted to achieve this through a complex system of bribes and offers of state positions to 'police' the other tribes of the region. This delicate balance was both a heavy drain on Constantinople's stretched treasury and highly unstable.

The system broke down in 1774 as Central Anatolia descended into a bloodbath of inter-tribal violence that the state could not control. In 1777, with this inter fighting having resulted in the pro-Republican tribes being heavily defeated, the Cumans turned westward and unleashed a year or horrific plunder across Greek-populated Western Anatolia. With Anatolia in ruins and popular anger at the regime boiling over, in 1779 a group of reactionary military leaders marched on Constantinople to overthrow the government and invite the exiled Emperor, Constantine XXII, to re-assume his throne to barely a single cry of unrest across the land. He would return as a true absolutist monarchy. With Byzantine Restoration stunned liberal sensibilities, with many having seen their cause as an unstoppable march of progress. Yet neither Germany, focussed on its western frontiers, nor Assyria, caught up by its internal politics, made any effort to resist the Restoration beyond mere protestations.

In Assyria, the first elections since the integration of Damietta were held in 1781. Lower Egypt's immense demographic shape necessitated the complete alteration of Assyria's political system, with constituencies greatly enlarged in size to accommodate the addition of the large new state. Politically, the Copts would reshape the Federal Republic as well. Lower Egypt was deeply conservative society, still slave-holding like Babylonia and Arabia, and their was particular revulsion at the Muslim Vizier leading the Republic. While the Moderates in particular made major inroads among the largely urbanised ethno-religious minorities of the state – Protestants, Old Copts, Jews and Nestorians – the great mass of Catholic Copts turned towards clerical, conservative and often anti-annexation candidates of the right. Elsewhere, in the historic territories of the Republic, the Moderates were also assailed by a pincer of advancing conservative and liberal opposition candidates. In the shocking final results, the Moderates lost their Majlis majority after three decades of unchallenged domination. The right, containing a ragtag and disunited band of Nestorian traditionalists, monarchists, regionalists in peripheral provinces like Pontus and Georgia, tribal leaders and a mass of Coptic conservatives, now outweighed the Moderates, although they lacked an anti-Republican majority in their own right.

The Republic had been betrayed by the ballot box, and its annexation of Damietta in particular appeared very fragile indeed. Despite this, the shattered Moderates under Agbar Israel were determined to maintain their grip on power.