1781-1790 The Return of Reaction

The 1781 election had changed the shape of Assyrian politics. The Moderates had lost their Majlis majority for the first time since Abaya's 1748 coup and were now outnumbered by the right wing opposition. Fortunately for the ruling group, the conservative block was far from unified, even by the standards of the day, with the Moderates and especially the Ishtarians having far greater unity around shared principles and organisations.

Within Assyrian conservatism, there were two main poles. Firstly, the clerical-monarchical Old Nestorians, dominant in Babylonia and the Gulf and a major force in rural Assyria-Superior and Nestorian communities throughout the Republic. They were motivated by pain in the exile of the traditionalist Patriarchate and monarchism above all else. Secondly, there were the Egyptians, the Copts and Latins of Lower Egypt who clung tightly to their Catholic faith and were focussed on the goal of restoring the Duchy of Damietta. In between, there were many others, Catholic conservatives in Philistia who were often both monarchist and close to the Egyptians, and the likes of the Georgian caucus who had little interest in an Imperial restoration in Nineveh or the Church politics to the south but rankled under their country's annexation into Assyria at the end of the Great Persian War. Others were even more local – representing traditionalists rejecting the power of central government and interference in social structures, a strong current among tribal communities in the mountains and deserts where the state's imprint was weaker.

Yet with the right so close to power, in the aftermath of the election there was a concerted effort to bring greater cohesion to the movement. The man who would undertake this task was Addai Seraphin, a blue blood aristocrat from Babylonia and the Malik of Wasit near Baghdad. His father had been a passionate Lebarian, fighting in the Civil War in the 1740s. Benefiting from the amnesties of Vizier Abaya, the Seraphins had retained their land, titles and slaves in Babylonia, yet remained unreconciled to the Republican status quo – with Addai himself entering the Majlis in the 1760s on an unabashedly monarchist platform. As one of the most senior of the Mesopotamian monarchist representatives, he appeared a natural leader among the Nestorian wing of the conservative movement with the Majlis as it grew rapidly in the 1770s. But the annexation of Damietta had provided opportunity to go further. Seraphin would devise a shared political platform for the Assyrian Right: the restoration of the Assyrian monarchy, the creation of a Kingdom of Egypt under the control of the local Catholic elite and in personal union with Assyria, the unification of the Church of the East under the Old Nestorian Patriarchate and its elevation to the status of state religion – while maintaining the traditions of Assyrian religious tolerance, the protection of land and property rights including slavery, the pursuit of compensation for lost titles and properties during the expropriations of the Revolution, greater decentralisation to the states and the weakening of the central government. This was a set of principles that were broadly acceptable to all the main conservative factions in Assyria. Indeed, Seraphin would even move to forge the basis for a true political organisation with the creation of the Saint George Society effectively a political club that drew influential figures from the various strands of the conservatism within the Majlis for the purpose of decision making. This marked the birth of a true conservative faction, seeking to challenge for power in its own right.

Conservative unity presented a major threat as the Majlis moved to elect a new Vizier. Desperate the maintain Republican power, Agbar Israel dismissed his many internal critics – calling for them to rally around him in the name of keeping the Right at bay. While the Moderates would seek to pick of elements of the Conservative coalition with offers of concessions and bribes, their main backing outside of their own ranks would come by looking to the small Ishtarian block in the Majlis, who held the balance of power. Cooperation with the Ishtarians had been a major taboo since the Decemeber Massacres in 1765-66. The willingness of the Moderates to deal with the liberals did much to dispel their extremist image, legitimising them before the Assyrian mainstream.

While the Israel ministry struggled on, paralysed by the gridlocked Majlis and building frustrations among his own supporters who had been used to perpetual untrammelled power, the Vizier would find solace in a quick and victorious war in the east. The borders of the Assyrian East Indies had been largely static through the eighteenth century, given the instability of the Revolutionary era, but soft power, in particular emanating from Sumatra – the jewel of Assyria's Empire – had seen Assyrian tentacles tighten around many of the small indigenous states of maritime South East Asia. Angered by this growing influence, in 1782 the Sultan of Brunei expelled Assyrian merchants from his realm and invaded the lightly defended colony of East Borneo, occupying the territory and threatening to invade Sumatra through the allied Emirate of Malacca on the Malaya archipelago. These grand ambitions were cut short by the arrival of the Republican Navy – which crushed the Sultan's fleet off the coast of Sarawak and placed all of Borneo under a naval blockade. With troops later arriving from the Middle East to defeat Sultan on land, a peace was agreed by the end of the year with Brunei ceding a hefty tribute, agreeing to reopen his country to Assyrian commerce and seeing his allies in Malacca annexed. Victory reaffirmed the importance of Nineveh to the East Indian colonies, a reminder to Sumatra in particular of the importance of the motherland, and boosted the Republic's prestige at home.

The 1770s had seen the Second Roman Republic effectively destroyed by its Turkic problems, and Assyria was not immune. On face value, the Cumans were not unlike other semi-nomadic pastoralist populations within Assyria, including Kurds and Bedouin Arabs. Yet they were set aside by an extreme martial culture that had led some in times gone past to label them the Spartans of the Near East. The Cumans had migrated to the Middle East and, in larger numbers, Anatolia during the Middle Ages. In Assyria, they could be found in three disparate parts of the Republic – in Pontus, in truth the eastern finger of Anatolian Cumania, they dominated the highlands and played a large role in the main city of Trabzon, while the Greeks lived on the coastal lowlands. In Philistia, they were as much as a tenth of the population – living mostly among their fellow Catholics west of the Jordan River. Finally, in Assyria-Superior, Cumans were around 5-10% of the population, with tribes scattered throughout the state, with greater concentrations in the mountains and especially on the shores of Lake Urmia near the Persian frontier. Over time in both the Byzantine and Assyrian Empires that had developed traditions of military service for the state and raiding. In Assyria, it was tradition for all Cuman males to spend a decade or more of their youth as a warrior before retiring to marry and take up the life of a herdsman, ready should a time of need come.

During the Revolution, the Cumans – so long associated with the monarchy – were looked upon suspiciously, with many of their warriors fighting for a variety of anti-Republican factions during the Civil War. With the end of the Great Persian War, the Federal Republic began to demobilise its sprawling armed forces and sought to reduce the outsized role of Cumans within it – leading to a steady drop in the demand for Turkic soldiery and military expertise. During this prolonged period of peace with no war, and far fewer opportunities for military service, an entire generation of Cuman youth passed by without being blooded as warriors, a fundamental right of passage before manhood among their culture. Repulsed by the fading of their traditions, and in part inspired by the explosion of violence in Byzantine Anatolia in the 1770s, tribes in Assyria began to form warbands and conduct blood feuds among one another and raid other semi-nomadic and settled populations. This problem was particularly significant in Assyria-Superior, where Cuman activity sparked a domino effect with many Kurdish highland tribes militarising in response and both posing a serious threat to many rural communities in the Republic's heartland. The government responded with a heavily military presence, but faced by the mobility of the raiders and often unforgiving terrain they struggled to completely end the Turkic problem.

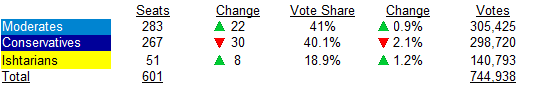

After the delicately poised 1781 vote, the 1784 elections were among the most bitterly contested in the post-Revolutionary history of the Republic with Addai Seraphin promoting a single Conservative platform from the Nile to the Persian Gulf. His dreams of sweeping to power with an anti-Republican majority would ultimately fall narrowly short, as the Right were just four seats shy of control of the Majlis. The real victors were the liberals, who saw a steady increase in their vote, share of the chamber and most importantly of all the importance of their parliamentary support in keeping the monarchist monster at bay. Assyrian liberalism had grown greatly in confidence over the past three years, enjoying a degree of respectability it had not held in a generation and drawing attraction as the militant defenders of the Republic. They would push a much harder bargain with the Moderates than in 1781, calling for a ban on monarchist and anti-Republican organisations, accusing the Saint George Society of flagrantly disregarded Abaya-era laws outlawing seditious bodies and more importantly, action on the issue of slavery. With the Moderates ditching Israel, refusing to endorse him for another term as Vizier and instead turning to the Antiochian Greek Michalis Sabetos to lead them, they could not accept the former without risking civil war but agreed to address the latter. Remarkably, after a Druze, a Jew and a Muslim, Sabetos was the first Christian Vizier since 1748.

The slave issue had been reignited by great changes abroad. While Assyria was the dominant player in the Indian Ocean slave trade, the Atlantic trade was dominated by Scotland, with its colonies in Brazil, the Caribbean and North America importing millions of Africans over the past two and a half centuries. While Scotland had been an opponent of the eighteenth century revolutions, it had undergone a peaceful and evolutionary path towards constitutional monarchy and possessed its own liberal traditions, distinct from the legacy of Assyrian Ishtarianism. A part of this was an abolitionist movement. In 1782, this movement achieved its greatest victory as Scotland banned the importation of new slaves into the Scottish Americas. While existing slave populations would remain under bondage, and the smuggling of slaves into Scottish territories through third parties,most significantly the Byzantine port of New Athens at the mouth of the Mississippi continued, the single largest source of demand for African slaves in the world had been severed. It was the largest move towards the end of the trade globally since the initial efforts at abolition in Assyria during the Revolution.

These changes had great consequences in Assyria. Firstly, they caused economic hardship and disruption among commercial elites and the Cape in particular. Much of East Africa's slaves did not remain within the Indian Ocean world, but were exported, via the Cape, to the Americas. Now this lucrative trade was gone and the value of slaves dropped significantly. Politically, Assyrian abolitionists were ashamed to see the Scots surpass their achievements in taking such significant action while the Indian Ocean trade remained alive and undisturbed. The Ishtarians in the Majlis, were therefore determined to end this trade once and for all, as a first step towards a future outright emancipation.

While the Vizier pursued an agenda against the slave trade, he found himself tearing the Moderate coalition apart. A clash emerged between the authority of the Vizier and his allies – who wished to pursue legislation that would limit or abolish the trade in line with his alliance with the Ishtarians – and a rebel faction of Moderates who ensured that an anti-reform majority in the Majlis could block him at every turn. This group was led by a young rising star among the Moderates, Chozai Petuel. The Moderate rightwiner was an ethnic Assyrian from Kirkuk, an unusual background for a defender of the peculiar institution. He rallied opposition to the Vizier around several axes: not only slavery, but a wider failure to secure the Republic by addressing the rise of the Conservative Right. A follower of the New Nestorian Church, he demanded that the state move towards reconciliation with the Old Church and pursue a religious settlement that would bring the Republic's largest faith into the fold. The Moderate caucus was increasingly raucous and divided in these years, with the Majlis barely able to function.

The 1787 election was one of relative stasis in voting preferences, but the small changes that did occur were of great significance. The Moderates regained their status as the leading block in the Majlis, narrowly short of a majority while the Conservatives shed thirty seats. The Ishtarians on the other hand, increased their incrementally yet again – exceeding their vote tally in the last pre-December Massacre election held a quarter of a century ago for the first time. Although less reliant on liberal votes than he had been in the past, Sabetos renewed his relationship with the Ishtarians to secure his re-election as Vizier, promising to continue to work to find a parliamentary majority for reform.

The liberal constitution of 1742 had emancipated several tens of thousands of black slaves in Syria and Assyria-Superior. Despite so much of that constitution being abandoned following Malik Abaya's seizure of power half a decade later, those blacks in the northern parts of the Federal Republic retained their freedom. The story of these black freemen in the decades after the emancipation was a sorry one. Pushed from the land by the growth of a smallholding peasant class during these same revolutionary upheavals, the blacks slowly flowed into the major cities of the region. There, they were shunned by state authorities and the local populace alike – denied access to the trades, still controlled by guild-like organisations, other gainful employment and all but the worst housing stock. They were pushed to the margins of urban life and developed into an underclass prone to begging, criminality and prostitution. Anxieties about the black freemen in the northern cities had been growing for some time, but spilt over into a full blown moral panic after two blacks were arrested for murder of a well-known merchant and his wife in Aleppo in a failed robbery in 1788.

With polite society in an uproar, the Conservatives seized the initiative to tap into sectors of the population that had hitherto shunned them in the cities. Their leader, Seraphin, argued that the blacks were in capable of of surviving in a civilised society under their own direction, arguing that the state must replicate the conditions of bondage they had previously lived under by taking the freemen into their control as a type of 'government serf', removing them from the cities and putting them to work on public projects. This proposition proved highly popular, and soon the Conservatives appeared to be gaining ground on territory they had previously feared to tread. With the Ishtarians stoutly defending the liberty of the freedmen, while they continued to work alongside the Vizier in pursuit of legislation on the slave trade, many Moderates were fearful for the very continuation of the Republic under its present course. In this mood, Chozai Petuel captured the mood of the faction to seize control of the leadership of the Moderates within the Majlis, ousting Sabetos' allies. Owing to the constitution, the Vizier would remain in office, but he was no longer in power.

Firmly under Petuel's leadership, the Moderates entered the 1790 election on a platform promising end the exile of the Old Nestorian Patriarch, bring the blacks in the northern cities to heel – although not going to the extremes of Conservative ideas, and swore to end all attempts to interfere with the institutions of slavery. The result was a stunning victory. The Moderates gained significance support at the expense of Right, seeing their close rivals of the past decade lose around a third of their seats and almost a quarter of their vote – neutralising them as an immediate threat to the existence of the Republic. While Petuel made major gains on his right flank, he lost out on his left. A number of Moderates who had been aligned to the outgoing Vizier had run in alliance with the liberals in 1790, combining with them to see the Left make a sizeable electoral breakthrough. Having won the Moderates' first parliamentary majority in a decade, Petuel was thunderously elected as Vizier, marking a shift in Assyria's political evolution.