1790-1802 The Man Who Would Be King

1790-1802 The Man Who Would Be King

Chozai Petuel, perhaps more than any man since Malik Abaya, had a grand sense of destiny for both himself and the Assyrian Republic, seeking to bring grandeur and elevation to both. His first aims were to resolve the immediate crisis arising from the racial panic in the cities of Syria and Assyria-Superior and, most significantly, bring an end to the exile of the Old Nestorian Patriarchate.

The first of these aims was the simplest and most brutal. Dismissing the Conservative proposal of a return to effective bondage under the control of the state for the blacks, Petuel borrowed from the history of the Jews, adopting a policy of ghettoisation. The blacks would remain free, but would be legally restricted from living or even exiting without permission defined neighbourhoods within the cities in which they resided. In effect, Petuel sought to place them out of sight and out of mind for the majority. These black ghettos, although small, would become dens of poverty with vanishingly few sources of outside income beyond charity from the churches that provided enough food to keep their inhabitants from famine.

The government's largest goal was religious reconciliation. However, this would be no easy task. Entreaties to India found that the Old Nestorian Patriarch, Rubil IV, refused to countenance a return to his ancestral see in Assyria, thereby legitimising the Republic, unless he was recognised as the sole head of the Church of the East and all the properties that had been lost during the Revolution were returned. These demands were nearly impossible for the state to meet. Therefore, negotiations stalled with little progress being made.

Pressure was building on the Moderates and Petuel in particular. They had attracted many religious voters in 1790 on the promise that the Patriarch would return, and the anti-Republican right appeared poised to capitalise on any disappointment. Salvation arrived for the Vizier in 1792 when the Patriarch of the New Nestorian Church based in Nineveh died at the unusually young age of 49 after contracting malaria. Pouncing on this opportunity, the state shed its commitments to secularism to intervene in the resulting assembling of bishops to appoint a replacement. Facing heavy handed pressure from the government, the bishops issued an encyclical calling the exiled Old Nestorian Patriarch to return to Nineveh and lead an ecumenical council leading towards the unification of the Church of the East.

Rubil delayed responding for some months to consider this proposal, with the Assyrian state publicly ending all legal impediments to his return. In late 1792, the Patriarch crossed into Assyrian Malabar, where he was greeted by massive crowds numbering in their 100,000s who chanted for a “one God, one Church, one Patriarch”. Seeing the enthusiasm of the St Thomas Christians, he set sail for Basra. Rubil's arrival on Assyrian soil was a moment of mass outpouring of religious ecstasy, as the ambition of millions of Nestorian traditionalists unfolded before their eyes. Rubil marched on foot from Basra to Nineveh, being following and visited by untold numbers of the faithful who wished to see the return of true religion to their land with their own eyes.

Despite the superficially strong hand of the New Nestorian bishops in the resulting council, the Republican Church possessing far fewer parishioners but most of the Nestorian Church's historic properties in the northern states of the Republic and a more established position within the Republic and its halls of power, massive popular pressure would force them to concede on almost every point of doctrinal and structural dispute with the traditionalists. Aside from a small number of New Nestorian dissidents who could not accept the member, the Unified Church of the East would bring the wider Nestorian religious community back together under a traditionalist leadership in 1793. As such, much of the anger would permanently ebb from Assyrian Conservatism.

Riding a tide of political euphoria among Nestorians, Petuel secured a thumping re-election in 1793. Taking two thirds of the Majlis, the Moderates' best performance since 1778, the party inflicted heavy losses on the Conservatives as traditionalist religious voters continued their drift towards the centre. Indeed, the entire character of the right wing contingent in the Majlis underwent a notable reorientation away from Mesopotamia and towards Egypt, where its Catholic voter base was unmoved by the Church of the East's reconciliation. For their part, although falling to modest parliamentary losses, the liberals saw their vote hold steady as they continued to consolidate their position as a significant critic of the Moderates' turn to the right.

Buoyed by electoral glory, Petuel's government would take an imperial turn in the middle of the decade. Its first target was the small, independent, Kingdom of Malta. In recent decades the central Mediterranean had grown into the site of regional power struggles. With their restored monarchy, the Byzantine sought to re-exert their much weakened influence, to the south the Italians had conquered the historically Egyptian lands of Tunis and Tripoli while Sicily itself was controlled by an independent Kingdom. All three coveted the rich, strategic island of Malta – that had preserved its independence for generations in the shadows of great powers. The Assyrian were eager to exert their own influence westward, taking the island as a base from which they could project power across the Mediterranean. In 1795, they deployed an armada to invade the island and overwhelm its well-manned fortifications – annexing Malta as a province of the Federal Republic.

The Maltese adventure was merely a preclude to a far larger expedition in the Far East. The expansion of the Assyrian Indies had largely ceased a hundred years before. Petuel had personal ambitions to end this stagnation and make rich new conquests in the region. His target was the Tagalog Archipelago stretching from Mindanao, north of Sulawesi, to Luzon in the north. These lands were divided between the Sultan of Manyila in the north, ruling from the island of Luzon, and the Raja of Sunda in the south, the master of western Java who also controlled much of Mindanao and the nearby islands, and some smaller local rulers. As Assyria lay claim to the entire archipelago, the two main indigenous rulers – traditionally rival Muslim and Hindu powers – united in alliance against the invasion. Despite this cooperation, the Assyrian far eastern fleet was able to crush their enemies at sea, ensuring complete control of the waves for the invaders and allowing for an invasion force to set out for Mindanao in early 1796.

Domestically, Petuel was a critic of the 1780 constitution, believing that it had left the government of Assyria too divided by overly weakening the Vizier at the expense of the Majlis. Petuel hoped to use the significant political capital he had amassed through his role in mending the Nestorian schism to remedy this fault. Keeping the bulk of the 1780 constitution in place, which was widely respected among his fellow Moderates, he secured important revisions that gave the Vizier effective free reign over foreign affairs and the ability to overrule the Majlis on domestic issues in limited circumstances. Crucially, the Viziership would be decoupled from the deliberations of the Majlis. No longer would the head of state be elected by the parliament, instead, the Vizier was to be chosen by direct election according to a plurality of enfranchised voters - proving a direct and personal endorsement by the citizens of the Republic – and would serve for two terms of the Majlis, six years in all, rather than requiring more regular re-election.

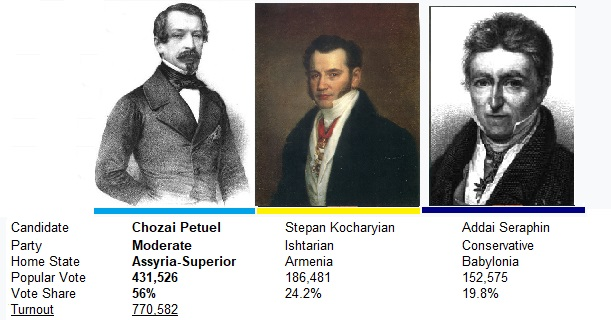

First Vizieral Election Result, 1796

Majlis Election Results, 1796

The 1796 election would be the first to be contested under the new system. They would prove to be a great individual victory for the sitting Vizier. Running against two rival candidates from the left and right – an ageing Addai Seraphin standing for the Conservative right and a ally of the former Vizier Sabetos who had drifted over to the liberals, the Armenian deputy Stepan Kocharyian, being chosen as the Ishtarian contender. Petuel won a convincing majority of the popular vote, notably outshooting the Moderates' performance in the Majlis election held on the same day. The vote underlined Petuel's enduring allure on the right, with tens of thousands of voters who supported Conservative parliamentary candidates giving him their support. As such, while the Conservatives remained the second faction in the Majlis, the liberals secured a clear second place in the Vizieral election.

From the moment of domestic political triumph, Petuel and his government would be brought crashing to earth by a catastrophic turn in the Tagalog War. The early stages of the campaign began well, with the expedition to Mindanao successfully overcoming a number of local rulers and pushing the Sundanese to pull back from the island. In 1797, filled with heady expectations of imminent victory, the Assyrian expeditionary force, already tired after months of hard battles, pursued the Sundanese to the smaller island of Panay to the north of Mindanao. Little did they know that the Raja Sikander I had managed to reach the archipelago, nor the scale of the Sundanese force that had concealed itself on the island. The Assyrians had walked into a massacre. Their army was almost completely destroyed, with the weak remnants losing control of most of Mindanao once more, retreating to the island's western Zamboanga peninsula. The defeat was a humiliation that put the entire expedition at risk of failure. Rather than admit defeat, the government would seek to call up fresh troops from the citizenry of the Middle East. Over the next two years, the southern island would become a meatgrinder as the Sudanese were joined with Manilyan forces from the north in a desperate struggle to push the Assyrians back into the sea.

In the face of a deteriorating military situation, unpopular conscription and angry criticism from right and left the Moderates walked into disaster in the 1799 Majlis election, representing the first 'mid term' vote in the new Assyrian election cycle between Vizieral votes. The Moderates plumeted to their lowest ever vote share and seat tally, with both the Conservatives and Ishtarians making sweeping gains. It was a harsh rebuke for the government, which was left unable to command majority support in the Majlis and as a result robbed of any ability to carry forward a legislative agenda.

In the aftermath of his 1799 humiliation, the Vizier took the risky and legally unconstitutional decision to travel out to the Indies to personally oversee a grand army that had been gathering to revive the Assyrian dream of conquest. Over the next two years a vicious campaign saw control over Mindanao fall firmly back into Assyrian hands, opening the way for a direct assault on Luzon and the Manilya Sultanate. During this period, Petuel pioneered a policy of offering military commissions to Cuman and Kurdish chiefs, seeking to redirect the militant energies of their warbands to fuel the colonial war effort – a policy with uncomfortable echoes of the Imperial era that angered many in Assyria. The war culminated Cagayan in 1801 at which a large Assyrian force heavily defeated the Manilyans and secured effective dominance over the Tagalog Archipelago. By the end of the year a peace treaty would bring an end to the bloody conflict. Assyria annexed the entire island of Mindanao directly as a colonial province, as well as the Rabaul islands off the coast of Papua – territories than had been outlying Sudanese possessions, while the Sultanate of Manyila was reduced to the status of an Assyrian vassal. From near disaster, the Vizier had snatched a great victory – expanding the Assyrian colonial empire more than any other ruler had managed to in a century and glorifying his own person.

In the last decades of the eighteenth century, economic and technological changes had been brewing that would change the world more profoundly than any that had come before since the dawn of human civilisation. This was the beginning of the industrial revolution. This economic transformation had its origins in the political changes unleashed by the liberal political revolution in Germany. While Assyria, and indeed Byzantium, had seen relatively little change to their economic structures during their Republican Revolutions, in Germany, Revolution had allowed market forces to be unleashed wholesale onto a society that had the wealth, resources, individual genius and technical expertise to be the hearth of industrial change. The heart of the revolution lay in discoveries around steam power and locomotion, new mining technology and labour-saving improvements in agriculture. Combined, these allowed for the exploitation of Germany's massive coal reserves and their conversion into power, the like of which the world had never seen, and significant increases in agricultural output to facilitate population growth while pushing thousands towards the cities where they would be a cheap source of labour for emerging factories and sweat shops. By the end of the century, these changes had transformed Germany into a beacon of economic and technological progress, streaks ahead of anything seen around the world, and the advancements of the industrial revolution were already spreading to the British Isles, Scandinavia, Italy and France.

Despite possessing an advanced political system and close diplomatic links to the Germans, Assyria lagged woefully behind. Its economy remained based on agriculture and trade. Meanwhile, for centuries Assyria, much like other Asian economies including Persia, India and China, had enjoyed the fruits of an established artisanal manufacturing base that had dwarfed its European counterparts. These more primitive manufacturies, often run by insular minority groups including Jews, Armenians in Syria and Mesopotamia and Protestants in Egypt, saw little need to adopt the new technologies transforming Europe and continued to use ancient methods and approaches, at much smaller scale. Assyria was falling behind.

Second Vizieral Election Results, 1802

Majlis Election Results, 1802

Final victory in the Tagalog War could not have been better timed for the Vizier, who returned to Assyria as a conquering hero in the mould of the venerated Malik Abaya just in time for a new election campaign. Petuel received the adulation of the masses, even as his militarism, disregard for the constitutional norms and self aggrandisement were a cause for concern among the political elite who instinctively feared a slip back towards personal rule. At the ballot box, Petuel won a heavy personal mandate as he was re-elected as Vizier for another six year term, having already served for more than a decade. He notably outperformed the Moderate parliamentary candidates, who, while regaining their Majlis majority on Petuel's coattails fell significantly short of the dominant display of their leader. The Ishtarians performed relatively strongly, retaining their popular vote in the Majlis vote despite a Moderate resurgence, while their Vizier candidate Stepan Kocharyian finished in second place once again. For the Conservatives, it was an especially painful election. Not only did they see the bulk of the Majlis gains they had made in 1799 wiped out, they saw their Vizieral candidate perform abysmally. With the old master of Assyrian Conservatism, Addai Seraphin, stepping towards retirement, the Egyptian wing of the movement had asserted their right to leadership. Yet the Latin-speaking Egyptian nobleman Cesare de la Bourg lost significant support among the Nestorians of Mesopotamia, who were reluctant to fall in line behind a Catholic. Going into a new century, Chozai Petuel was well on his way to second decade dominating Assyrian political life.

- 7

- 2