Akrotatos III (1328 AD - 1348 AD)

Akrotatos III (1328 AD - 1348 AD)

Akrotatos III ascended to power in the Grand Duchy of Taurica and was elected Emperor of Taurica with the support of four electoral votes following the tragic death of his brother, Molon IV, in July 1328 AD. His rise to the throne occurred in an atmosphere of tension and speculation, as some suspected he had a hand in the previous ruler's death.

Nevertheless, his position was strong due to the backing of key electors and the loyalty of the army. Unlike his brother, Akrotatos III was not known for his diplomatic skills, but his military and administrative competence was exceptional, surpassing even his predecessor in some aspects.

The new emperor was well aware of his limitations in diplomacy, which is why, during the reigns of his father, Molon III, and brother, Molon IV, he actively participated in negotiations and the development of foreign policy. His involvement in these areas allowed him to gain valuable experience and build a network of contacts that proved crucial after his ascension. Conscious of his shortcomings, he surrounded himself with advisors skilled in diplomacy, who supported him in negotiations and shaping the empire's external policies.

Akrotatos III assumed power at the age of 39, also as a widower. His first wife, Empress Philotera Kalmidis, came from an influential local noble family but tragically died during the birth of their second son, Theodotos.

At the time of his ascension, Akrotatos III had four children—his eldest son and heir, Spartokos, his younger son Theodotos, and two daughters, Mika and Helena. The death of his wife delayed his thoughts of remarriage for many years, but imperial advisors saw a new marriage as an opportunity to strengthen the Zoticid dynasty's influence.

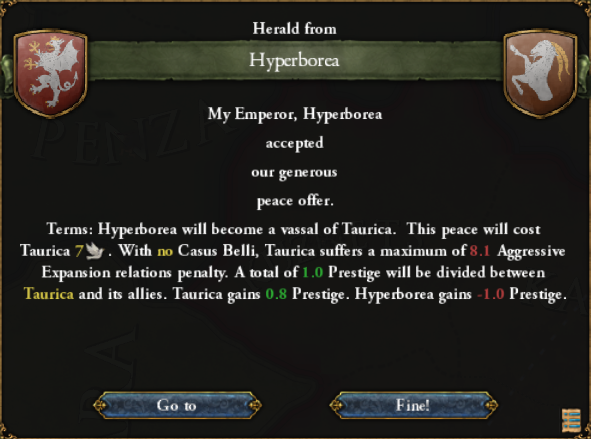

After careful consideration, Philaenis, the sister of the Grand Duke of Hyrcania, Memnon III Kanavos, was chosen as the new empress. This decision was not only a dynastic calculation but also a political one, as Hyrcania was a key region on the empire's eastern frontier. Memnon III Kanavos, though ruling independently, had strained relations with neighboring states and needed a strong ally. The peace terms following the war with the Kingdom of Kurus created favorable conditions for strengthening ties between Hyrcania and Taurica.

The marriage between Akrotatos III and Philaenis was arranged relatively quickly and without significant resistance, largely due to the favorable peace treaty. Hyrcania regained its lost territories under the agreement, which was a priority for Memnon III. The mutual commitments between Hyrcania and Taurica gained even greater significance, as this alliance stabilized the situation in the east, where threats from neighboring states remained real.

The marriage not only strengthened the Zoticid dynasty's position but also effectively integrated Hyrcania into the Taurican domain. Shortly after the wedding, Memnon III agreed to recognize Akrotatos III as his sovereign and formally subordinate his duchy as a vassal of the Grand Duchy of Taurica.

The death of Heliodoros I Philetid in 1330 AD without a direct heir created an excellent opportunity for Akrotatos III to expand the Zoticid dynasty's domain. The Grand Duchy of Tanais was directly incorporated into the grand ducal holdings, significantly strengthening Akrotatos III's position in the empire.

The annexation of these lands not only increased political influence but also ensured full control over the trade routes passing through Tanais, which were crucial for both internal trade and external exchange with neighboring states.

However, this decision faced opposition from distant members of the Philetid family, who claimed rights to the lands of Tanais as relatives of the late grand duke. To avoid a major rebellion and regional destabilization, Akrotatos III proposed a compromise—part of the lands was granted to lesser members of the Philetid family as fiefs, and in return, they recognized the full suzerainty of the Taurican ruler, becoming minor nobility within the Grand Duchy of Taurica.

Additionally, financial compensation in the form of gold and silver helped settle claims and maintain relative peace. This allowed Akrotatos III to avoid a prolonged internal conflict and effectively absorb Tanais into the Zoticid domain.

In the fall of 1330 AD, two major rebellions broke out in the Taurican Empire, threatening the stability of Akrotatos III's rule. The first occurred in Gorgippia, where local nobility, dissatisfied with the rule of a vassal prince and distant relative of the emperor, rose against his authority.

The second rebellion erupted in the Uyra province and was more dangerous, as it stemmed from peasant discontent and directly challenged Akrotatos III's authority. The peasants, unhappy with heavy taxes and wartime conscription, took up arms, hoping to exploit the weakened central control after recent conflicts with Kurus.

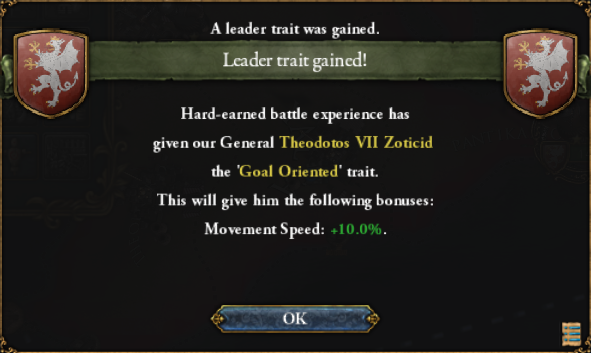

Akrotatos III, aware of the gravity of the situation, decided to personally lead the campaign against the rebels in Uyra, entrusting the suppression of the Gorgippia rebellion to the experienced commander Philippos Phouskarance. The emperor, known for his military prowess, quickly assembled an army and took action.

His forces clashed with the rebels in a series of brutal battles, with the decisive engagement taking place in February 1331 AD, when the rebellion was finally crushed. The peasants, lacking a trained army or sufficient resources, stood no chance against the disciplined imperial troops. After the victory, Akrotatos III imposed harsh reprisals to prevent further uprisings—the rebellion's leaders were executed, and some villages were razed as a warning to others.

Meanwhile, Philippos Phouskarance successfully dealt with the noble rebellion in Gorgippia. His forces defeated the rebellious lords in a series of skirmishes, with the decisive victory coming in April 1331 AD. The defeated nobles were forced to swear loyalty to Heliokles I, and part of their estates was confiscated for the imperial treasury. Unfortunately, this victory marked Philippos's last triumph—the seasoned commander died shortly after the campaign, likely due to illness or exhaustion.

In the summer of 1332 AD, Akrotatos III decided to launch a military campaign against the Grand Duchy of Aorsia, seeing it as a natural target for further strengthening the Zoticid dynasty's power. Aorsia, located on the eastern frontiers of the Taurican Empire, had weak ties to the rest of the empire and maintained closer relations with the Kingdom of Kurus and the nominal Emperor of Volga-Ural.

For Akrotatos III, who sought to expand his direct suzerainty, subjugating Aorsia meant both securing the eastern borders and strengthening the Zoticid dynasty's dominance. The pretext for the war was ongoing border skirmishes, involving mutual raids and plundering, which allowed the emperor to present the conflict as a defense of imperial interests.

The war began on June 12, 1332 AD, when Taurican forces crossed the Aorsian border and launched a campaign to quickly capture strategic cities in the region. Akrotatos III, as an experienced commander, led the offensive with great determination, aiming to resolve the conflict in his favor before Aorsia's potential allies could intervene.

The war with Aorsia, which initially seemed like a quick conflict, turned into a prolonged struggle when, in 1334 AD, the Kingdom of Kurus decided to support its ally and attacked the Taurican Empire.

Kurus, possessing one of the most powerful armies in the region, invaded imperial territory, directing its forces toward Gorgippia—a key city on the Maeotian Sea. Akrotatos III, aware of the threat, decided to divide his forces.

He continued the campaign against Aorsia, while entrusting the defense of the southeastern borders to his general Artemidoros Paraspondylos, giving him a 20,000-strong army. His task was to halt Kurus before it could join forces with Aorsia and threaten the heart of Taurica.

The decisive confrontation occurred on August 6, 1334 AD, in the Second Battle of Gorgippia. The Kurus forces, numbering around 25,000 soldiers, included heavy cavalry and numerous infantry units, which advanced toward the city, hoping to quickly break through the imperial defense. Artemidoros, though outnumbered, used the terrain to his advantage, fortifying his position on the hills and forcing the enemy to attack uphill. The battle began with intense archery exchanges, but the crucial moment came when Kurus's heavy cavalry launched a frontal assault on the imperial center.

Paraspondylos anticipated this maneuver and positioned his best spear-armed infantry in the center, while the imperial cavalry hid on the flanks. When the Kurus forces struck, the imperial infantry held the initial charge, and on the general's command, the Taurican cavalry executed a sudden flanking maneuver.

This attack turned the tide of the battle—the Kurus forces, caught between two fronts, began to retreat, and their lines collapsed. After several hours of fierce fighting, the Kurus army was forced to withdraw, leaving thousands dead and wounded on the battlefield. The victory at Gorgippia solidified the empire's position in the conflict and allowed Akrotatos III to continue the conquest of Aorsia without fear of a southern attack on his territories.

In January 1335 AD, after two years of intense fighting, Akrotatos III made peace with the Grand Duchy of Aorsia, sealing the imperial victory. Under the treaty, Aorsia was forced to cede key territories—Balakovo, Ukek, and Ordy—which were incorporated into the Zoticid domain, significantly expanding the Grand Duchy of Taurica's territories to the north and east.

Additionally, Aorsia was required to pay 11 gold obols as war reparations, further weakening its economy and underscoring Akrotatos III's dominance in the region. This peace treaty solidified the Zoticid dynasty's position as the primary expansionist force in the empire.

After concluding the war with Aorsia and securing the newly acquired territories, Akrotatos III turned his attention to the last independent grand duchy on the empire's eastern frontier—Thyssangeti. Its geographical location made Thyssangeti particularly vulnerable to raids by the Golden Horde, and the lack of strong allies left its ruler seeking ways to secure his lands against external threats.

Akrotatos III recognized this weakness and, instead of waging a costly war, opted for an intense diplomatic campaign to draw Thyssangeti into the Zoticid sphere of influence. The negotiations were lengthy and required numerous concessions, but ultimately, a favorable agreement was reached. A key element of the deal was the marriage between the emperor's daughter, Helena, and the heir to the Thyssangeti throne, Tanatos.

This alliance not only strengthened ties between the two dynasties but also ensured that future generations ruling Thyssangeti would be linked to the Zoticid dynasty, guaranteeing lasting imperial influence in the region. The ruler of Thyssangeti, Tanatos I, understood that his sovereignty would become largely symbolic, but in return, he received strong protection against nomadic raids, which was a crucial concern for him.

The culmination of these negotiations was the formal act of homage by Tanatos I to Akrotatos III. Importantly, this homage was paid not to the Taurican Emperor but directly to the Grand Duke of Taurica, signifying that Thyssangeti's lands were incorporated into the Zoticid domain. This was a key political move, further strengthening the dynasty's position. Through this bloodless expansion, Akrotatos III achieved another success in his strategy of building the Zoticid dynasty's power. The inclusion of Thyssangeti into the sphere of influence not only expanded their territories but also created a buffer against threats from the Golden Horde.

Between 1335 and 1340 AD, the empire experienced a period of relative peace, allowing Akrotatos III to focus on internal affairs. News from the north reached the imperial court in Satyria—the Kingdom of Bjarmaland had plunged into civil war. Reports suggested that the conflict stemmed from the local nobility's opposition to King Jormoj II's ambitions to strengthen central authority by curtailing aristocratic privileges.

In Bjarmaland, the civil war intensified as Jormoj II refused to compromise, viewing his reforms as necessary for modernizing the state. The nobility, fearing the loss of influence, formed a coalition demanding the restoration of feudal freedoms.

Meanwhile, from distant Iberia came news of a groundbreaking discovery by the Kingdom of Adberia. In recently conquered territories in North Africa, vast gold deposits were found, solving the kingdom's financial problems caused by a severe shortage of the precious metal. This resource not only bolstered Adberia's treasury but also enabled further military expansion and trade development in Africa.

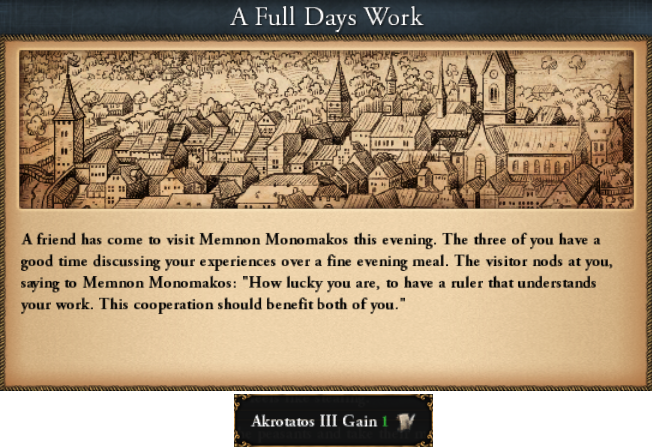

Memnon Monomakos, one of Akrotatos III's closest advisors, was a key figure in managing the finances and fiscal policy of the Grand Duchy of Taurica. In 1336 AD, he published a literary work on trade, gold circulation, and fiscal matters, which became a foundational textbook for the treasury administration in the region for many years.

His work was based on in-depth analyses of the economic mechanisms operating in the empire, as well as observations of markets and tax systems used in other states. Thus, his work served not only as a compendium of financial knowledge but also as a practical guide for future generations of administrators.

Monomakos served as an advisor on taxes, trade, and administration, being one of the most important officials in Akrotatos III's government. His ability to manage the imperial treasury and negotiate additional subsidies from noble families significantly strengthened the state's finances.

During his tenure, he repeatedly demonstrated that he could secure funds without overly burdening the populace, increasing their loyalty to the emperor. Moreover, his pragmatic approach to trade allowed for the development of merchant networks and the stabilization of the gold market, which was crucial for the economy of the entire duchy.

The trust Akrotatos III placed in Monomakos stemmed not only from his competence but also from his dedication and diligence. Monomakos was known for his extraordinary conscientiousness and constant search for solutions to improve the state's economic situation.

His collaboration with the emperor resulted in numerous reforms in the treasury administration, which improved tax collection and reduced bureaucratic corruption. He advocated for fiscal transparency and sought to ensure that both the nobility and commoners had clearly defined tax obligations, reducing the risk of corruption and social unrest.

His approach to financial management was based on fairness toward Akrotatos III's subjects. Monomakos believed that the state should not overburden its citizens but rather ensure economic stability and invest in urban development and infrastructure.

The reforms implemented under his supervision significantly improved relations between the emperor and his subjects, as they limited unfair tax enforcement and favored a system where everyone had clearly defined obligations to the treasury. This earned Akrotatos III a reputation as a just ruler, strengthening his authority among the people.

The emperor himself reaped tangible benefits from having such an outstanding finance minister by his side. Working with Monomakos allowed him to expand his knowledge of economics and fiscal policy, making him an even better administrator.

Many historians argue that without Monomakos's advice, Akrotatos III's economic policies would not have been as effective, and the Zoticid dynasty's territorial expansion would have been far more limited.

The economic prosperity brought about by the collaboration between Monomakos and Akrotatos III not only filled the imperial treasury but also enabled the dynamic development of cities and villages in the Zoticid-controlled territories. Significant tax revenues and trade income allowed for investments in infrastructure, leading to the emergence of new urban centers.

One of the most spectacular examples of this development was the city of Urgast, which, after being incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Taurica, quickly transformed from a small settlement into an important administrative and trade hub. With the support of the emperor and influential noble families, Urgast became a strategic point on the eastern frontiers of the Zoticid domain.

Under the patronage of Akrotatos III and local aristocracy, the city began attracting merchants, craftsmen, and settlers, leading to its rapid growth. New marketplaces, workshops, and public buildings were constructed, and well-planned streets and a defensive system made Urgast one of the most modern cities in the region.

Culture also flourished—temples, libraries, and academies were established, drawing scholars and artists. In a short time, Urgast became a symbol of Akrotatos III's economic success and an example of how wise financial management and efficient administration could lead to prosperity for both the elite and ordinary citizens.

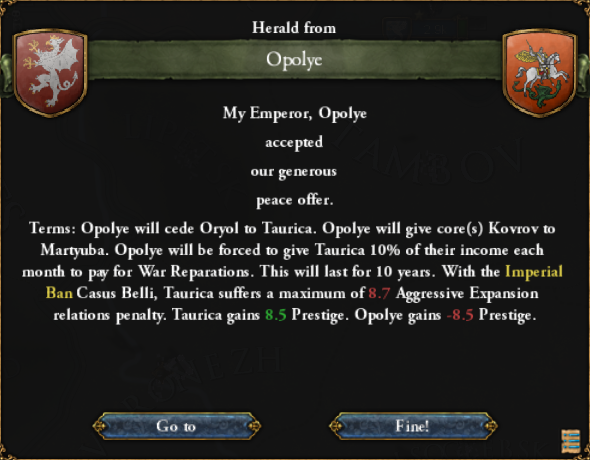

In 1336 AD, Akrotatos III launched a campaign against the Duchy of Opyle, which had occupied lands considered by the empire to be an integral part of its territory. The disputed regions of Obinsk and Orylo were of strategic importance for the security of the Grand Duchy of Taurica's northern border. Initially, the campaign proceeded smoothly, as imperial forces captured key fortifications.

However, the situation became complicated when Duke Tylmech II of Opyle received support from other imperial houses, including the Grand Duchies of Androphagia and Theophilisia. Their intervention prolonged the war and turned it into a more complex conflict, requiring Akrotatos III to engage in both military and diplomatic efforts.

Despite his military superiority, the emperor had to consider that prolonged warfare could deplete his resources and provoke further internal unrest.

Between 1338 and 1339 AD, the war continued with mixed success for both sides. Imperial forces managed to hold their territorial gains in Orylo, but Opyle successfully defended Obinsk, and the support of Tylmech II's allies slowed further progress.

Akrotatos III faced a difficult choice—continue the costly campaign or seek a negotiated solution. Faced with mounting losses and internal pressure, the emperor agreed to peace talks, resulting in a treaty signed on November 11, 1340 AD.

Under the agreement, Opyle ceded Orylo to Akrotatos III, while the land of Kovrov returned to the Duchy of Martyub. Additionally, Duke Tylmech II was required to pay war reparations to the Grand Duchy of Taurica for the next ten years, partially compensating for the failure to achieve all war objectives.

However, the situation changed again shortly after the peace treaty was signed. A civil war broke out in the Duchy of Opyle, weakening Tylmech II's rule and undermining his ability to regularly pay reparations. Akrotatos III closely monitored the situation, ready to intervene if the internal conflict in Opyle created an opportunity to expand the Grand Duchy of Taurica's influence. Although the war of 1336–1340 AD did not end in total victory, the emperor used diplomacy and economic pressure to secure his gains.

Between 1341 and 1344, the second major conflict of the period took place when the Kingdom of Colchis seized the lands of Majar following a peasant uprising. The rebels, discontented with their previous rulers, sought the protection of the King of Colchis, who accepted them under his sovereignty and declared the conquered territory part of his kingdom.

This situation was unacceptable to Akrotatos III—not only did it threaten the integrity of the Empire, but it also demonstrated that subjects could evade his rule by aligning with external forces. This posed a direct challenge that the emperor had to address with decisive military action.

After assembling his army, Akrotatos III launched a campaign to reclaim Majar and punish those who had committed treason. The fighting lasted three years, and while Colchis initially offered strong resistance, it gradually lost control over the contested territories under the relentless pressure of the imperial forces.

Ultimately, after a series of battles and grueling sieges, the Colchian side acknowledged its defeat and agreed to peace negotiations. As part of the treaty signed in 1344, Colchis renounced all claims to the lands of Majar, which were officially incorporated into Akrotatos III’s domain. Additionally, as a condition of the peace, Colchis was required to pay 40 obols in gold as compensation for the damages and regional destabilization caused by the conflict.

The life of Akrotatos III came to a sudden and tragic end. On March 11, 1348, the emperor died in a hunting accident. The exact details remain unclear, but according to accounts from the courtiers accompanying him, his horse was startled on uneven terrain, and the fall proved fatal.

The death of Akrotatos III was a tremendous blow to the Zoticid dynasty and the Grand Duchy of Taurica as a whole, as the emperor was regarded as one of the greatest rulers of his time. Through skillful administration, military strategy, and economic policies, he had significantly strengthened the state's position.

Following his death, the throne of the Grand Duchy passed to his eldest son, Spartokos VIII, who quickly secured the support of the electors and was chosen as the next Tauric emperor.

- 1