Uh oh , the Henries are finally starting to show up . I was waiting for that to happen XD . The war of the roses was an intense and dramatic set of events in the real history and I'm very impressed at the parallelship yet originality which you portray it in your alternate history , JM . Well done !

O Lord, our God, Arise: More Weekly Reports from England

- Thread starter unmerged(10971)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Kurt_Steiner: He's not much of a match for the historical Henry II, unfortunately.

canonized: Well, only the first one's a Henry--since there were more Staffords in real life, I'll be following their line at first...

- - - - - - - -

Polydore Vergil was an Italian scholar who in 1504 came to England to serve as Bishop of Bath and Wells. There, he was commissioned by King Edward VI to write a history of England, a massive 26-book undertaking which was not completed until 1533, more than a decade after Edward's death and the beginning of Henry III's reign. This excerpt is from the section on the Battle of Richmond, containing the part about George's death.

Hwer for, cannung fastlice þaet se daeg aeihweþer wolde geald to him ane friþsome 7 bliþe rice fram þans forþ, oþer elles aefre beryf him of þe same, cam he to þe stow wiþ coren on his heafde, þaet þer by he aeihweþer miht macie ane beginnung oþer ane ende of his rice. 7 swa se soroglic mann had faerlice swilc ane ende hwilc is gewona befallan to þaem þat havaþ riht 7 lagu boþ of God and mann in lice eahtung, eall swa willa, impietie, 7 arleasnes. Sicorlice þese sind mare stearc bispelles by micel þan cann be araeden wiþ tounge afyrhtan þase menn hwice geferaþ noht tima agan freo fram sum healic scyld, reþnes, oþer yfeldaede.

canonized: Well, only the first one's a Henry--since there were more Staffords in real life, I'll be following their line at first...

- - - - - - - -

Sources of the English Language, no. 4

Historia Anglica (English History) by Polydore Vergil

[excerpt]

Historia Anglica (English History) by Polydore Vergil

[excerpt]

Polydore Vergil was an Italian scholar who in 1504 came to England to serve as Bishop of Bath and Wells. There, he was commissioned by King Edward VI to write a history of England, a massive 26-book undertaking which was not completed until 1533, more than a decade after Edward's death and the beginning of Henry III's reign. This excerpt is from the section on the Battle of Richmond, containing the part about George's death.

Hwer for, cannung fastlice þaet se daeg aeihweþer wolde geald to him ane friþsome 7 bliþe rice fram þans forþ, oþer elles aefre beryf him of þe same, cam he to þe stow wiþ coren on his heafde, þaet þer by he aeihweþer miht macie ane beginnung oþer ane ende of his rice. 7 swa se soroglic mann had faerlice swilc ane ende hwilc is gewona befallan to þaem þat havaþ riht 7 lagu boþ of God and mann in lice eahtung, eall swa willa, impietie, 7 arleasnes. Sicorlice þese sind mare stearc bispelles by micel þan cann be araeden wiþ tounge afyrhtan þase menn hwice geferaþ noht tima agan freo fram sum healic scyld, reþnes, oþer yfeldaede.

Last edited:

The War of the Roses had interesting ending.

About Polydore Vergil. The title of his book is Historia Anglica.

About Polydore Vergil. The title of his book is Historia Anglica.

Nice ending of the Roses. It shall prove to be interesting to see how the Stafford line wears the English crown. Shall this be the times in which the world trembles at the sound of Englishmen? Or the times in which the world takes pity on the ruin of glorius England?

Olaus Petrus said:About Polydore Vergil. The title of his book is Historia Anglica.

Whoops. That's what I thought I'd put there, but apparently a "c" slipped in there somehow. Bloody typos.

Crookback makes some of the nicknames sound tame. Poor Tower Princes. Enjoyed the excerpT.

Draco Rexus: Yes, this is certainly a new age in England. The story of the Stafford family will evolve over time, however, with good kings and bad kings (and good queens and bad queens).

JimboIX: Even poor Renaud was only known as "ill-starred". Poor George has been given a bit of a bad rap by history, though, to say nothing of the Bard.

canonized: Eh, those awards feel diluted by me after the last one where anonymous kept pushing back the voting deadline. I may be a bit hypocritical here, seeing as how I am with deadlines and obligations all, but if you've set a timetable with people it might be best to have them stick to it.

- - - - - - - -

BEGINNINGS

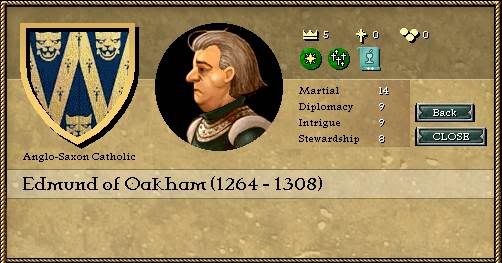

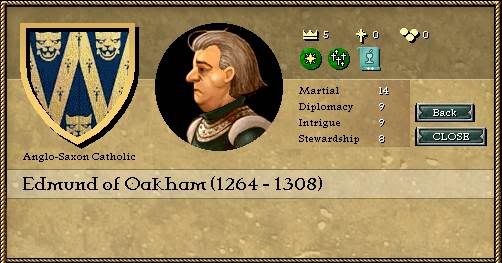

One of the strange facts about the Stafford family is that, for all their apparent devotion to the Anglo-Breton culture of the de Cornouaille period, their family line seems to be descended from the Saxon nobility. The shadowy Edmund of Stafford who was made the first Baron Stafford in 1299 was said to be in his mid-thirties at the time of his appointment, and noted in the last pages of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as being "of the native aristocracy". The records of the Church of St. Mary in Warwick notes the baptism in 1264 -- exactly 35 years before Edmund's appointment -- of Edmund of Oakham, fourth son of Harold, Thane of Warwick. Stafford itself lies not too far north of Warwick, making a connection tantalizingly possible.

Edmund of Oakham-Stafford, 1st Baron Stafford

FROM STAFFORD TO BUCKINGHAM

Little else is known or even suspected of Edmund (killed fighting alongside Prince Amaury in the revolt against Renaud), but his son became the true founder of the dynasty as a local political force. Rolf of Oakham-Stafford, who to advance his career took the French name of Ralph de Stafford, made a name for himself in the 1320s as a courtier during the regency of John I. He had done so well that when scandal erupted in 1336 over his abduction of Margaret, daughter of the Earl of Gloucester, the young king sided with him, allowing them to marry.

Ralph was alongside John during the famous crusade to the Greek Isles, and by the time the expedition returned in 1344 he was one of the most famous knights in the Kingdom of England. Ralph had commanded a section of the cavalry that had charged up the hill at Rethymnon, and for it and other matters of service was made Earl of Stafford in 1350. Ralph also took part in King William's campaigns in Iceland and Ireland, ending a long and fruitful life in 1372.

His heir was Hugh, who thanks to his parentage was not only Earl of Stafford but Lord Audley. Hugh fought in the civil wars surrounding the early reigns of kings Alfred and Dewi, showing near equal prowess to his father.

From here, the Stafford family did little of note until the reign of Ioan II. The Earl at the time was Humphrey. He took part as a knight in the final (Johannine) stage of the Hundred Years War, fortunately avoiding taking part in the Battle of Pontremy. Humphrey did well enough in the Frisian War -- commanding the central regiment of knights which split the Oldenburg and Muenster armies at Westerstede -- that he was appointed Duke of Buckingham in 1444.

FROM BUCKINGHAM TO ENGLAND

He soon found himself, like the rest of the English nobility, embroiled in the Wars of the Roses. Humphrey himself refused to take sides, but his eldest son (also named Humphrey) had married the daughter of the Duke of Somerset and was alongside Somerset at the battle of Galston, where both were killed. The elder Humphrey mourned the loss of his son but refused to avenge him. Necessity soon drove him to the Welsh side of the conflict, however, and he took part in the Battle of Monmouth. Despite the success of his side in that battle, he shared the fate of the opposing commander, being killed by a fluke arrow shot early in the fighting.

The Duchy of Buckingham now went to the six-year-old Henry, son of the younger Humphrey. Young Henry was brought up in the court of King Edward IV, and caught the eye of the queen, Elisabeth Woodville. This proved very unfortunate for the young man, who in 1466 was married to the queen's sister Catherine, twelve years his senior.

This was the turning point in his life. The marriage cause him hatred of the Woodville family, and by extension Edward IV. When that king died in 1483, he soon found himself alongside George, Duke of Clarence, supporting that man against two children of the Woodvilles: the Princes in the Tower. Stafford's part in their death is not known but likely, even if he was able to later pin their deaths on George. Within two months of George's seizure of the throne, however, Henry was at the head of an army against him. The proceeding events have already been covered, leading to the Stafford family taking the English throne.

JimboIX: Even poor Renaud was only known as "ill-starred". Poor George has been given a bit of a bad rap by history, though, to say nothing of the Bard.

canonized: Eh, those awards feel diluted by me after the last one where anonymous kept pushing back the voting deadline. I may be a bit hypocritical here, seeing as how I am with deadlines and obligations all, but if you've set a timetable with people it might be best to have them stick to it.

- - - - - - - -

History of the Stafford Family to 1485

Arms of the Stafford family: Or on a chevron gules a Stafford knot of the first on a chief azure a lion passant guardant of the field.

Arms of the Stafford family: Or on a chevron gules a Stafford knot of the first on a chief azure a lion passant guardant of the field.

BEGINNINGS

One of the strange facts about the Stafford family is that, for all their apparent devotion to the Anglo-Breton culture of the de Cornouaille period, their family line seems to be descended from the Saxon nobility. The shadowy Edmund of Stafford who was made the first Baron Stafford in 1299 was said to be in his mid-thirties at the time of his appointment, and noted in the last pages of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as being "of the native aristocracy". The records of the Church of St. Mary in Warwick notes the baptism in 1264 -- exactly 35 years before Edmund's appointment -- of Edmund of Oakham, fourth son of Harold, Thane of Warwick. Stafford itself lies not too far north of Warwick, making a connection tantalizingly possible.

Edmund of Oakham-Stafford, 1st Baron Stafford

FROM STAFFORD TO BUCKINGHAM

Little else is known or even suspected of Edmund (killed fighting alongside Prince Amaury in the revolt against Renaud), but his son became the true founder of the dynasty as a local political force. Rolf of Oakham-Stafford, who to advance his career took the French name of Ralph de Stafford, made a name for himself in the 1320s as a courtier during the regency of John I. He had done so well that when scandal erupted in 1336 over his abduction of Margaret, daughter of the Earl of Gloucester, the young king sided with him, allowing them to marry.

Ralph was alongside John during the famous crusade to the Greek Isles, and by the time the expedition returned in 1344 he was one of the most famous knights in the Kingdom of England. Ralph had commanded a section of the cavalry that had charged up the hill at Rethymnon, and for it and other matters of service was made Earl of Stafford in 1350. Ralph also took part in King William's campaigns in Iceland and Ireland, ending a long and fruitful life in 1372.

His heir was Hugh, who thanks to his parentage was not only Earl of Stafford but Lord Audley. Hugh fought in the civil wars surrounding the early reigns of kings Alfred and Dewi, showing near equal prowess to his father.

From here, the Stafford family did little of note until the reign of Ioan II. The Earl at the time was Humphrey. He took part as a knight in the final (Johannine) stage of the Hundred Years War, fortunately avoiding taking part in the Battle of Pontremy. Humphrey did well enough in the Frisian War -- commanding the central regiment of knights which split the Oldenburg and Muenster armies at Westerstede -- that he was appointed Duke of Buckingham in 1444.

FROM BUCKINGHAM TO ENGLAND

He soon found himself, like the rest of the English nobility, embroiled in the Wars of the Roses. Humphrey himself refused to take sides, but his eldest son (also named Humphrey) had married the daughter of the Duke of Somerset and was alongside Somerset at the battle of Galston, where both were killed. The elder Humphrey mourned the loss of his son but refused to avenge him. Necessity soon drove him to the Welsh side of the conflict, however, and he took part in the Battle of Monmouth. Despite the success of his side in that battle, he shared the fate of the opposing commander, being killed by a fluke arrow shot early in the fighting.

The Duchy of Buckingham now went to the six-year-old Henry, son of the younger Humphrey. Young Henry was brought up in the court of King Edward IV, and caught the eye of the queen, Elisabeth Woodville. This proved very unfortunate for the young man, who in 1466 was married to the queen's sister Catherine, twelve years his senior.

This was the turning point in his life. The marriage cause him hatred of the Woodville family, and by extension Edward IV. When that king died in 1483, he soon found himself alongside George, Duke of Clarence, supporting that man against two children of the Woodvilles: the Princes in the Tower. Stafford's part in their death is not known but likely, even if he was able to later pin their deaths on George. Within two months of George's seizure of the throne, however, Henry was at the head of an army against him. The proceeding events have already been covered, leading to the Stafford family taking the English throne.

Last edited:

Henry is Humphrey's grandson, I assume? I enjoyed the family's backstory, it integrated them into the fabric of the kingdom well, which makes their accession seem less jarring. Even better that they're anglo-saxon in the male line.

One of the things I've always liked about British history is the constant struggle for legitimacy on the crown not just between members of the same family but amongst powerful lords so these chapters on the wars of the roses are great . I think you also add a nice documentary voice to this AAR especially in this last chapter .

Judas Maccabeus said:When that king died in 1483, he soon found himself alongside George, Duke of Clarence, supporting that man against two children of the Woodvilles: the Princes in the Tower. Stafford's part in their death is not known but likely, even if he was able to later pin their deaths on George. Within two months of George's seizure of the throne, however, Henry was at the head of an army against him. The proceeding events have already been covered, leading to the Stafford family taking the English throne.

Glad to see that Stafford didn't manage to loose his head this time and got a crown for it.

A bit of luck doesn't hurt.

JimboIX: Yep, added in a little line in there after noting your comment. Am I ever glad I have you people to do factchecking, I'd never get it all right myself!

canonized: And then Parliament jumps in there every once in a while, making things even more of a mess...

Olaus Petrus: Too bad he's not directly (or even really indirectly) descended from the Siwardings, but ah, well, good enough, eh?

(Actually, the correct heir of the Siwardings {thanks to the fact that Osric II wasn't inherited through his daughter but his nephew} would be the Kings of Spain. You'll excuse me if I don't let them in, especially not in a certain year called 1588.)

Kurt_Steiner: Not to mention a stronger and more assertive Wales. Historically the Welsh would probably have been only too happy to cut off his head and send it to George--I mean, Richard--on a platter just because it gave them a rare opportunity to kill an Englishman and get back for the last few centuries.

Next update should be tomorrow, Henry II's reign. I've been putting quite a bit of work into this one (particularly on one map) so I hope it comes out right.

canonized: And then Parliament jumps in there every once in a while, making things even more of a mess...

Olaus Petrus: Too bad he's not directly (or even really indirectly) descended from the Siwardings, but ah, well, good enough, eh?

(Actually, the correct heir of the Siwardings {thanks to the fact that Osric II wasn't inherited through his daughter but his nephew} would be the Kings of Spain. You'll excuse me if I don't let them in, especially not in a certain year called 1588.)

Kurt_Steiner: Not to mention a stronger and more assertive Wales. Historically the Welsh would probably have been only too happy to cut off his head and send it to George--I mean, Richard--on a platter just because it gave them a rare opportunity to kill an Englishman and get back for the last few centuries.

Next update should be tomorrow, Henry II's reign. I've been putting quite a bit of work into this one (particularly on one map) so I hope it comes out right.

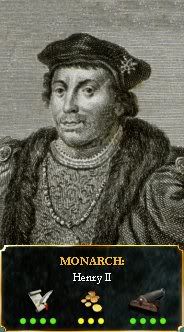

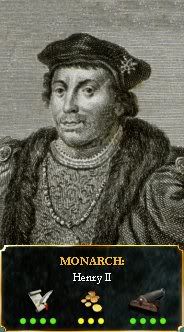

Henry II

Born: 4 September 1454, Stafford

Married: Catherine Woodville (in March 1466)

Died: 2 November 1503, Salisbury

Born: 4 September 1454, Stafford

Married: Catherine Woodville (in March 1466)

Died: 2 November 1503, Salisbury

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

King of England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland [and France]

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duke of Buckingham, Holland and Friesland, Cornwall, [Iceland and Bretagne]

Earl of Stafford, Count of Guines

With Richmond gone there was nobody left to threaten Henry's claim to the throne. The de Cornouaille family had basically committed mass suicide in the bloody previous years, and all that was left were weak marital connections: the Neville family had joined the de Cornouailles in that fate, and Jasper Tudor was not the rallying figure his nephew had been. There would be only one threat to Henry's throne, and a weak one at that: the revolt of Lambert Simnel.

Simnel was not a member of royalty, nor even the nobility of his native Flanders. Instead, he was from the lower parts of the region's growing middle class, and had no real delusions of being anything more. In fact, he was only ten years old when, in 1487, a priest named Roger Simons brought him to the Earl of Kildare, one of the few loyal Irish lords. "Loyal" was a relative term, for while Gerald Fitzgerald professed homage to the English crown he was a devoted Cornwallist. Simnel provided an opportunity to claim a pretender to the English throne.

Unfortunately, he made one massive error. Simons said that he should be presented as Richard, younger of the "Princes in the Tower". It was a sensible option, as there was enough doubt as to the Princes' fate for people to believe that he was alive. Kildare had heard a rumor, however, that another claimant--Edward of Warwick, son of Clarence--had also died in the Tower, under Henry's custody. Simnel was two years closer to Warwick in age (he was four years younger than Richard), and so the claim was made.

Ireland was a horrible place to lead a revolt from, however, and the northern parts of England were disloyal enough (with no concern as to who was actually on the throne, it should be noted) to provide a decent army to fight Henry with. In fact, the city of York had only seen fit to allow Henry in on 29 May 1485 and no earlier, as a protest to the death of Richmond. Into this stew appeared Simnel and his guardians two years later, and by June they had gathered 19,000 men, including the Earl of Lincoln.

King Henry was astounded. He thought he had accounted for all the potential threats; they were either dead or in his custody. But when he heard that the young boy was claiming to be Warwick, he immediately calmed down. Warwick was not, in fact, dead, but quite alive, and it was with that child that Henry marched northward at the head of the English army.

Henry entered York with the child on 13 August 1487, amazing the people of the region. The news quickly reached the haphazard rebel army encamped near the famous Sherwood Forest, and within days half of the force disappeared. It did not help that Simnel himself did not inspire much confidence; Simons had not bothered to coach the boy in proper English, and so he spoke in his native Dutch. He could still be understood, but gave himself away as a middle-class Fleming and not the nephew of an English king. The rest moved on to the village of East Stoke, where, on 26 August 1487, Henry attacked.

The battle was quick. The Cornwallists at first held the high ground, but realizing that their army's morale was dropping rapidly, Kildare and Lincoln ordered a charge. Within an hour it was over: Lincoln was dead, with Kildare, Simons, and Simnel captured. Kildare would be executed; Simons was saved by his ecclesiastical position (although he would be imprisoned for life) and Simnel was given no blame, being merely a puppet. He would be placed in the royal household and serve Henry II and his heirs for years to come.

But the beginning of Henry's reign was not entirely devoted to fighting rebellion. He also intended to continue the reforms of the English governmental system that had begun during the reign of Edward IV. This increased the power of the middle class, but Henry's next weapon against the nobility was all his own: the Star Chamber and the justices of the peace.

The two were the main instruments in Henry's campaign against the system of "livery and maintenance". Livery allowed servants of nobles to wear their master's symbols, which not only gave them considerable power but extended the noble's authority as well. Maintenance was the most problematic of the results of the livery system: the private bands, who acted similar to the later Sicilian Mafia, would interfere with the legal system to ensure that their master could get away with anything.

The Star Chamber was a secret court set up to try some of the worst crimes: treason, sedition, libel, and so on. What pushed it from being simply another secret court into becoming so effective (and such a violation of the concepts of jurisprudence) was that it could try and convict people even if they technically did not break the law, but instead performed actions that the court believed should be illegal. It did its job, but at a severe price, as would be seen later on.

A 19th-century drawing of the Star Chamber Court

Less problematic was the network of justices of the peace. The system of justices, pulled from the local gentry (they were required to have an annual income of £20, well past the lower classes of the time), had existed for quite some time, beginning more as policemen (empowered to arrest but not try criminals) but slowly gaining more power over the centuries. Slowly, they gained more powers, until under Henry II's reign they became the main system of authority in England and Scotland. They were to enforce Acts of Parliament, replace jurors seen as corrupt, and ensure that proper weights and measures were used. Certain low-level crimes could even be tried and sentenced by the justices alone.

What must be re-emphasized in that previous paragraph is that this took effect in both England and Scotland. Henry sought to break the power of the Scottish Parliament, who had merely stood by as problems occured to the south and kept quiet. Henry was a thorough man, however, and had no intention of leaving them alone. The Scottish Parliament was all but forced to, on 2 March 1490, pass a law giving Henry the same considerable control he wielded in England. They also subsequently went through some measures to fix the wide disparity in laws between the two kingdoms.

The domestic policies of Henry II's reign

By this point, Henry was well in control of the kingdom. A threatened rebellion by nobles in 1489 against the new legal system sputtered out, not even really getting started. He had quieted the Cornwallists through marriage: Elisabeth, eldest daughter of King Edward IV, was to marry his son Edward. However much Henry despised Elisabeth Woodville and her children, through her came an even stronger claim to the English throne, one which Edward intelligently decided not to use during his father's lifetime.

Now able to turn outward, he saw a Europe in equal turmoil. The death of Charles the Bold, Count of Burgundy, had caused the Babenburg family to gain a long stretch of land from the border of France to the border of Hungary, including in the middle the rich regions of Helvetia (modern Switzerland) and the Italian city of Milan. They were now in conflict with the King of Italy; when the Milanese revolted in 1485, the Austrians crushed it, only to soon find themselves thrown back by the Italians.

Henry had no intention of doing anything with the more tumultuous parts of European politics. Minor marriage alliances were contracted with the Holy Roman Emperor (the von Ardennen dynasty of Lower Lorraine), the King of France, and even the far-away King of Egypt. England's focus on trade also required foreign dealings; the most important was a not-so-foreign one, an argument with the Count of Geldre over harassment in Antwerp. This was resolved, and the other main dealing eventually proved positive.

This was with the Italian city of Genoa. Although part of the Kingdom of Italy, the main trading cities of the region were given some autonomy. One Genoese merchant, sent on a semi-diplomatic mission to London, became enamoured with the city and offered his services to the King as an engineer. Henry did not have enough money nor inclination (nor the merchant enough talent) to give him such a post, but the merchant moved on to other things. His true ability was sailing, and when he arrived in Bristol in 1495 he found a ready audience with the merchants there for funding of his next venture.

On 7 January 1497, with royal backing and a further £20,000 from the Bristol merchants for the setting up of trading posts and permanent settlements, Giovanni Caboto sailed for Asia, across the same ocean Christopher Columbus had only five years before.

Statue of Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot) in Newfoundland

Henry's reign has been prosperous and it will be interesting to see how future colonial adventures of England will fare.

Not a bad reign at all...for a usurper, anyway. I enjoyed the part about Lambert Simnell, there's an interesting book out by Anne Wroe called the perfect prince about Perkin you might be interested in...also found this while I was trying to remember the title, which I found amusing. Good update, interesting what you did with Warwick (the Plantagenet-er, Breton version anyway).

Discovered this a few weeks ago and finally found the time to read up on your alt-history. Amazingly rich and filled to the brim with detail. Good work on your alt-dynasties with great care to make the parallels to our timeline events a good read and fitting.

Good work and looking forward to the next weekly report!

Good work and looking forward to the next weekly report!

Cabot's expedition--three ships, his flagship being the Matthew--left amidst considerable celebrations from the people of Bristol. Anyone who could find an excuse congregated around the docks of the city, and dignitaries were only too happy to appear there and lend their moral support (and show that they were supportive in case the expedition succeeded). If Cabot succeeded, then England could prosper considerably from the trade with Japan and China; even if he didn't, it was an adventurous display of bravery, and made him an instant celebrity before he even left. Once he was gone, however, it was more a matter of breathlessly waiting for news of his exploits.

A replica of the Matthew in Bristol harbour

His first port of call after Bristol was the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik, on 1 April. Although the Althing routinely flouted royal authority, the island was still technically a part of the Kingdom of England, and allowing the three ships to dock and reprovision was a politically expedient move. Besides, even if they were feeling more rebellious they had no good reason to hinder him, as an English claim on whatever lands he would discover would not put the people of Iceland out of anything. The Viking spirit of discovery had long since passed, and the Icelanders were happy to work the land they already had.

About a month later, Cabot stopped at the Greenland port of Julianehab. Then, it was a relatively recent village hugging the coast, but it was enough for Cabot to make it his base for explorations southward. The old stories of "Vinland" and the strange people there might not have been in Cabot's mind, but many on those islands remembered the old sagas and their stories of Leif Eiriksson's voyage to nearby islands, and thus they felt that Cabot might quite reasonably find something useful. That was the hope when he set out a few days later to the southwest. It was on the 26th of May, 1497, that Cabot, entering the Strait of Belle Isle, saw a large continent to his right and the craggy northern point of an island to his left.

The first was an historic moment, the first sighting of the American* continent since the aforementioned Vikings. Cabot still considered himself the first to see it, and so did the people in England, making it appear all the more impressive. As he looked to the other side, he saw a newly-found island, which allowed him to figure out a very reasonable if boring name for it: Newfoundland (although he originally used the Latin Terra Nova). Cabot noted it and continued onward, following the shore of the mainland for a short time.

Cabot, like Columbus five years earlier (and Dinis Dias, the Portuguese discoverer of Brazil), thought he had reached islands off the coast of Asia. Specifically, Cabot placed himself a short distance to the north of Japan, thinking that a short voyage to the south would allow him to reach that fabled island, or perhaps even Cathay itself. So, he soon turned to the south, and around the beginning of June spotted another point of land. Excited, he continued southward along the coast, expecting at any moment to run across one of the great cities Marco Polo mentioned.

Instead, by 16 June all his expectations were drained away. By this point it was obvious that there were no millions here, and the people resembled the Mongols and Chinese only extremely superficially. He gave the areas he had found new names: The point became Cape Breton (for its resemblance to the Finisterre region of Bretagne), the land to the south Nova Scotia ("New Scotland"), and the bay in which he found himself the Bay of Fundy.** He wandered disappointed in the bay for a few days, only leaving after the 24th of June (on which day he named the St. John River).

Cabot slowly made his way along the coastline southward, until on 15 August 1497 he spotted a large harbour and a peninsula within it. Cabot knew a good thing when he saw it, and when he returned to Greenland on 1 November (on the return charting the southern and eastern coast of Newfoundland), sent a message back to England stating that it would be the best place for settlement. In fact, he intended to place a small group at the site as soon as the next spring arrived (leaving them there at the beginning of winter would have been suicidal).

The message caused a sensation when it arrived two months later. Nearly two hundred people came forward immediately asking to be allowed to settle at the new town, and on 23 May 1498 Henry II granted it a royal charter (by which time at least half of them were already on their way or even there). Since a large number of the early colonists were from the Lancashire village of Boston, they brought the name along with them. By 1502 the town boasted nearly 1,000 English inhabitants and an approximately equal number of natives (survivors of a smallpox outbreak which had decimated their tribe and would spread rapidly through America thereafter); their tribe name, Massachuset, would be given to the region from then on.

Early settlers of Boston smoking a pipe with the massasoit (Great Chief) of the Massachuset.

Meanwhile, Cabot was headed back south. In fact, he established the first English settlement in America on Newfoundland, the village of Stafford (near modern St. George's), on 29 January 1498. However, the attempted colony failed quickly, and by June the settlers had decided to leave for Boston. Cabot himself had been blown too far south, touching land not at Cape Cod as he had intended but in modern New Jersey. On 8 May he turned back north off the coast of Delaware, passing the still-unfinished town of Boston to return for Greenland. He would finally come to the port on 29 November and continue exploring from there. After making two more voyages, he reached his southernmost point on 20 December 1499. During that voyage he caught ill, and after the ships returned to Boston, he died on 25 March 1500.

Map of the voyages of John Cabot

While these matters were occuring in America, England continued its diplomatic overtures with the rest of Europe. Charles IV of France had died in April of 1498, succeeded by his cousin Louis VII. Louis had recently managed to annul his forced marriage to Louis VI's daughter Jeanne, and in 1499 he accepted the hand of Elisabeth, Henry's eldest daughter. With this came a treaty of alliance between the two countries and a recognition that Henry would no longer be isolationist in continental affairs.

He would not have long to apply his ideas, however. In late 1503 he became extremely ill, and died on 2 November. His son became Edward VI, in the first peaceful succession in England since Ioan II eighty years (and three violent successions) before.

__________

*The theory that Cabot himself gave it the name, after one of the Bristol merchants who financed him (Richard ap Meryc, or Ameryce, who at least was an actual high-ranking Bristol merchant) is tempting. However, it can most likely be discounted due to it being so recently put forth, and the fact that the mapmaker who first used the name specified that the inspiration came from the Latin form of Amerigho Vespucci. The one thing this theory has in its favour is that the name was applied to the northern continent of the New World instead of the southern; but accuracy in locations was not always a concern for people at that time, or Columbus (and Cabot) would not have thought he had reached Asia.

**The most commonly accepted theory for this name is from fondo, meaning, in Cabot's native North Italian, deep. One theory, however, connects it to a Latin word for "scattering", and thus, poetically, "defeat".

A replica of the Matthew in Bristol harbour

His first port of call after Bristol was the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik, on 1 April. Although the Althing routinely flouted royal authority, the island was still technically a part of the Kingdom of England, and allowing the three ships to dock and reprovision was a politically expedient move. Besides, even if they were feeling more rebellious they had no good reason to hinder him, as an English claim on whatever lands he would discover would not put the people of Iceland out of anything. The Viking spirit of discovery had long since passed, and the Icelanders were happy to work the land they already had.

About a month later, Cabot stopped at the Greenland port of Julianehab. Then, it was a relatively recent village hugging the coast, but it was enough for Cabot to make it his base for explorations southward. The old stories of "Vinland" and the strange people there might not have been in Cabot's mind, but many on those islands remembered the old sagas and their stories of Leif Eiriksson's voyage to nearby islands, and thus they felt that Cabot might quite reasonably find something useful. That was the hope when he set out a few days later to the southwest. It was on the 26th of May, 1497, that Cabot, entering the Strait of Belle Isle, saw a large continent to his right and the craggy northern point of an island to his left.

The first was an historic moment, the first sighting of the American* continent since the aforementioned Vikings. Cabot still considered himself the first to see it, and so did the people in England, making it appear all the more impressive. As he looked to the other side, he saw a newly-found island, which allowed him to figure out a very reasonable if boring name for it: Newfoundland (although he originally used the Latin Terra Nova). Cabot noted it and continued onward, following the shore of the mainland for a short time.

Cabot, like Columbus five years earlier (and Dinis Dias, the Portuguese discoverer of Brazil), thought he had reached islands off the coast of Asia. Specifically, Cabot placed himself a short distance to the north of Japan, thinking that a short voyage to the south would allow him to reach that fabled island, or perhaps even Cathay itself. So, he soon turned to the south, and around the beginning of June spotted another point of land. Excited, he continued southward along the coast, expecting at any moment to run across one of the great cities Marco Polo mentioned.

Instead, by 16 June all his expectations were drained away. By this point it was obvious that there were no millions here, and the people resembled the Mongols and Chinese only extremely superficially. He gave the areas he had found new names: The point became Cape Breton (for its resemblance to the Finisterre region of Bretagne), the land to the south Nova Scotia ("New Scotland"), and the bay in which he found himself the Bay of Fundy.** He wandered disappointed in the bay for a few days, only leaving after the 24th of June (on which day he named the St. John River).

Cabot slowly made his way along the coastline southward, until on 15 August 1497 he spotted a large harbour and a peninsula within it. Cabot knew a good thing when he saw it, and when he returned to Greenland on 1 November (on the return charting the southern and eastern coast of Newfoundland), sent a message back to England stating that it would be the best place for settlement. In fact, he intended to place a small group at the site as soon as the next spring arrived (leaving them there at the beginning of winter would have been suicidal).

The message caused a sensation when it arrived two months later. Nearly two hundred people came forward immediately asking to be allowed to settle at the new town, and on 23 May 1498 Henry II granted it a royal charter (by which time at least half of them were already on their way or even there). Since a large number of the early colonists were from the Lancashire village of Boston, they brought the name along with them. By 1502 the town boasted nearly 1,000 English inhabitants and an approximately equal number of natives (survivors of a smallpox outbreak which had decimated their tribe and would spread rapidly through America thereafter); their tribe name, Massachuset, would be given to the region from then on.

Early settlers of Boston smoking a pipe with the massasoit (Great Chief) of the Massachuset.

Meanwhile, Cabot was headed back south. In fact, he established the first English settlement in America on Newfoundland, the village of Stafford (near modern St. George's), on 29 January 1498. However, the attempted colony failed quickly, and by June the settlers had decided to leave for Boston. Cabot himself had been blown too far south, touching land not at Cape Cod as he had intended but in modern New Jersey. On 8 May he turned back north off the coast of Delaware, passing the still-unfinished town of Boston to return for Greenland. He would finally come to the port on 29 November and continue exploring from there. After making two more voyages, he reached his southernmost point on 20 December 1499. During that voyage he caught ill, and after the ships returned to Boston, he died on 25 March 1500.

Map of the voyages of John Cabot

While these matters were occuring in America, England continued its diplomatic overtures with the rest of Europe. Charles IV of France had died in April of 1498, succeeded by his cousin Louis VII. Louis had recently managed to annul his forced marriage to Louis VI's daughter Jeanne, and in 1499 he accepted the hand of Elisabeth, Henry's eldest daughter. With this came a treaty of alliance between the two countries and a recognition that Henry would no longer be isolationist in continental affairs.

He would not have long to apply his ideas, however. In late 1503 he became extremely ill, and died on 2 November. His son became Edward VI, in the first peaceful succession in England since Ioan II eighty years (and three violent successions) before.

__________

*The theory that Cabot himself gave it the name, after one of the Bristol merchants who financed him (Richard ap Meryc, or Ameryce, who at least was an actual high-ranking Bristol merchant) is tempting. However, it can most likely be discounted due to it being so recently put forth, and the fact that the mapmaker who first used the name specified that the inspiration came from the Latin form of Amerigho Vespucci. The one thing this theory has in its favour is that the name was applied to the northern continent of the New World instead of the southern; but accuracy in locations was not always a concern for people at that time, or Columbus (and Cabot) would not have thought he had reached Asia.

**The most commonly accepted theory for this name is from fondo, meaning, in Cabot's native North Italian, deep. One theory, however, connects it to a Latin word for "scattering", and thus, poetically, "defeat".

Very cool voyages JM ! I liked the diagram too ! As usual your footnotes are acres of gems .