canonized: Not well, sadly. Not through any fault of the Church, really, but things just turn into a mess in England, and Germany is a lost cause. Egypt's fine, though.

- - - - - - - -

Henry III Defender of the Faith

Born: 18 September 1501, Penshurst, Kent

Married:

[1] Catalina de Tarragona (on 11 June 1509)

[2] Anne Boleyn (on 25 January 1534)

[3] Margareta Greifen (on 1 April 1537)

[4] Jadwiga Przemyslowa (on 1 February 1539)

[5] Catherine Howard (on 28 July 1540)

[6] Salome von Zaehringen (on 4 June 1542)

Died: 7 July 1553, London

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

King of England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland [and France]

Prince of Wales

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duke of Buckingham, Holland and Friesland, Cornwall, [Iceland and Bretagne]

Earl of Stafford, Count of Guines

People almost invariably arrive at their beliefs not on the basis of proof but on the basis of what they find attractive.

Blaise Pascal

Young Henry III was a man of boundless energy, even more so than he is given credit for. When his father Edward died, he insisted that the planned diplomatic mission to France--which was growing ever more extravagant--should continue. So it was that a massive group of people, a peaceful army hundreds or even thousands strong, followed their new king south from Calais, just as an equally large gathering was moving north, led by King Francois I of France. On 7 June 1521, they met where the County of Guines ended and the Kingdom of France began, a border village named Balinghem, and set up camp.

Said camp would soon pass into legend as the

Champ du drap d'or, or the "Field of the Cloth of Gold". If the accounts are inflated even tenfold it more than deserved its name, as the area filled with tents of the most extravagant variety. Both kings were there not only for negotiations but to outdo each other. The expenses were enormous; not only was the expensive cloth named in the field's title used, but large amounts of glass (quite difficult to get at the time) and a fountain which dispensed wine. Henry's palace was nearly 100 meters long on each side--10,000 square meters, or 2.5 acres, larger than a football pitch--and ten meters high.

The Field of Cloth of Gold, by an anonymous painter (late 16th century)

It was not only a diplomatic meeting, but a tournament as well, in which both kings apparently acquitted themselves well. Alongside was feasting, dancing, music by the French composer Jean Mouton, and every sort of entertainment that money could buy and decorum allowed (and likely the latter existed secretly as well). For all it was worth, however, things rapidly turned sour, when after a wrestling match between the two kings (Francois won), they began to distrust and dislike each other. The meeting broke up on the 24th, with the two groups warily going home. The lavish display had achieved nothing of note other than to waste money.

And things were going quite poorly in England at this time. A plague rushed through the northern part of the kingdom in August, and the next year difficulties began to appear within the merchants over Protestantism. Thomas More, who was rising in importance and already well-known for his writings, worked with Cardinal Wolsey to encourage, "by hook or by crook" as the saying goes, German workers and merchants in London who had brought Luther's teachings with them. Henry himself sought to persuade through good words, and, with a small amount of help by More, wrote

A Defence of the Seven Sacraments, pointing out apparent flaws in Luther's theology.

Reaction was as would be expected. The few Protestants in the country didn't like it, Luther, whose stubbornness allowed him to point out real problems but caused him to go too far at times, spat back a reply more concerned with insults than with actual arguments. More merely worked to reply to Luther as well as he could, sometimes losing his own decorum and sending insults back. Pope Leo X recognised its logic to the point of naming Henry "Defender of the Faith", a title which was at the same time very fitting and yet ultimately ironic.

If Wolsey thought that such faith would keep Henry on good terms with England's greatest churchman, however, he was sorely mistaken. Henry secretly disliked the cardinal's great power within the kingdom, and slowly worked to undermine it. This gained him no friends amongst the church, not that he cared much: Henry was first and foremost out for himself, as later events would show. At the time it was more a difficult battle between two of the greatest men of their age. It very nearly burst into civil war when, in June 1525, Henry replaced Wolsey as chancellor with Sir Thomas More.

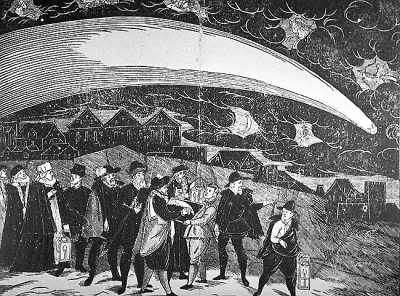

Wolsey had enough, and intended to use his power as permanent Papal Legate and practical controller of the English Church against his former ruler. Declaring that Henry had thus shown his contempt for the Universal Church (oh, how Wolsey could not have known), he excommunicated the King and called upon the people and nobles of England to replace him with Thomas Howard, the 3rd Duke of Norfolk and wife of Henry's sister, Elisabeth. The appearance of a comet later that month allowed him to show it as a sign from God of His disapproval of the current situation.

A 16th-century comet, by Jiri Daschitzky (1577)

But things soon fell apart for the cardinal. First, Pope Clement VII, never the most pious or intelligent of Popes but not foolish enough to ignore an obvious problem, revoked the excommunication and removed Wolsey's legateship. Second, Norfolk immediately stated his opposition to the plan (which had relied on Norfolk being ambitious enough to revolt), offering whatever security Henry felt necessary to prove his loyalty. Henry waved this off, knowing that Norfolk's declaration in and of itself would be enough to destroy the revolt. Revolts more connected with Inclosure struck the Midlands and the north during 1526 and 1527, along with a Scottish revolt in 1528 (connected with an outbreak of the "English Sweat")*. These are collectively known as the "Wolsey Rebellion", although the Cardinal himself was captured and imprisoned (saved from execution only by his ecclesiastical position) later in 1525.

During this time Henry also began to look to his navy, ordering its strengthening and instituting a Council of the Marine on 25 March 1530. The flagship of this new navy was the

Mary Rose, a 90-gun carrack built in 1510 and upgraded by Henry to serve as the centrepiece of a modern fleet. As for men, Norfolk had been Lord High Admiral but had resigned on 8 April 1525 (before the unpleasentness around him had started). In his place was Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and acknowledged illegitimate son of Edward VI.

England also began to expand rapidly in America. Along with the foundation of new colonies, which had boomed during the later part of Edward VI's reign and proceeded at a slow pace during Henry III's, the English pushed into territory claimed by the Iroquois Confederation, destroying the village of Manhattan on 7 October 1529 and replacing it with the colony of New York. A semi-organised tribe called the Lenape were defeated in 1533 and the area slowly settled by English colonists.

Catherine of Aragon, by Michael Sittow, 1502

Henry's concern was not with America, however. His marriage was rapidly falling apart, as the previous decade had not produced a son, and his wife, Catherine of Aragon (in Spanish, Catalina de Tarragona), was beyond childbearing age. Angry, he looked desperately for a reason for annulment; finally, he settled on the argument that the marriage had been against his will. It was an incredibly weak argument, and it would have taken the talents of a Wolsey or a More to argue it successfully. Wolsey was in prison, however, and More refused to even try.

Worse, the Austrians and Spanish, under Catherine's nephew Carlos I of Spain, had gained influence over the Papacy. Clement VII tried to fight them but soon found his own city raised against him, and when the Medici of Florence intervened, it revolted and was looted by its own citizens (6 May 1527). The Spanish family of the Borgias, projecting from Romagna, kept Clement in line and insisted that he go along with Carlos' decisions. Thus cowed, Clement would not listen to Henry's arguments even if there had been reason behind them. He never officially refused an annulment--he would have loved to weaken the influence of Carlos if he could--but instead delayed constanty.

Henry had had enough. He had already taken another lover, Anne Boleyn, and on 25 January 1534 married her. He was already convinced that Catherine's marriage could be dissolved, thus not making such a marriage bigamy;** the Pope would never approve, though, and Henry realised that. He thus looked to another method. Thomas Cranmer, a priest and family friend of the Boleyns, had recently been made Archbishop of Canterbury. After a quick review of the situation, he declared Henry's marriage annuled due to Henry's horribly weak excuse of unwillingness.

From this point, events occured quickly. Clement finally could not sit idly, and with Borgia and Medici armies sitting not far from Rome he had no choice but to side with Catherine. Henry and Cranmer were excommunicated, and the former declared to be bigamous. His court soon became divided, and when Thomas More spoke in favour of the Pope Henry removed him from his position and replaced him with a close friend, Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, who soon got Parliament in line, creating the Reformation Parliament of 1533-1534.

Thomas Cromwell, by Hans Holbein (1533)

Acts were passed in rapid succession: Restraint of Appeals in 1533, meaning that an act set forth by the King or one of his representatives could not be appealed to the Pope; Absolute Restraint of Annates in 1534, preventing payment to the Pope of any kind; the Treason Act in 1534, making it treason to refuse to acknowledge the next act;*** and most important of all, in November 1534, the Act of Supremacy. This made Henry the sole and highest authority in the Church of England, effectively removing any and all Papal control of English religious affairs. England was now officially Protestant.

__________

*The "English Sweat" was an epidemic disease which struck during several summers of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, almost always in the British Isles (except for the 1528 outbreak, which spread across Europe). The cause is not known.

**An

annulment is different from a divorce in that, in the former, the marriage is stated to have never existed.

***To be exact, it was passed after the Act of Supremacy and referred to it, but some license has been taken here for the sake of a better-flowing list.