Cabot's voyages were a great success and I think that soon there will be English colonies everywhere on the North American coast.

O Lord, our God, Arise: More Weekly Reports from England

- Thread starter unmerged(10971)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Oh, what a great hero of daring and skill! Braving the seas and the unknown to discover new lands. A time of excitement in the home isles surely!

It seems that civilized men have not set foot on the newly found lands yet. Is that true? Or have other men, from Asia or worse, our dastardly foes from the continent, settled there too?

It seems that civilized men have not set foot on the newly found lands yet. Is that true? Or have other men, from Asia or worse, our dastardly foes from the continent, settled there too?

canonized: Yes, I figured that any description of mine would be repetitive and definitely miss important parts of it, so I decided to just show you all in map form.

Olaus Petrus: It'll take a while, though, and there'll be some problems along the way. I wouldn't have it otherwise.

Sir Humphrey: Ah, nice to hear some praise and see someone other than the "usual suspects".

Kurt_Steiner: Yep, things are going to settle down for a bit, which is exactly what England needs. Edward VI isn't the best ruler rating-wise, but that takes away from the peace he'll oversee.

TeeWee: Sadly, the Spanish have already begun setting down colonies in Antillia, while the Portuguese colony of Brazil on the Columbian continent is already several decades old by this point. But the Portuguese are friendly, and Brazil is far away, so I'm not going to begrudge them that. As for France, well, they're happily messing around rather uselessly with Africa.

- - - - - - - -

Next update is likely tomorrow, although if I can get it in later today I will.

Olaus Petrus: It'll take a while, though, and there'll be some problems along the way. I wouldn't have it otherwise.

Sir Humphrey: Ah, nice to hear some praise and see someone other than the "usual suspects".

Kurt_Steiner: Yep, things are going to settle down for a bit, which is exactly what England needs. Edward VI isn't the best ruler rating-wise, but that takes away from the peace he'll oversee.

TeeWee: Sadly, the Spanish have already begun setting down colonies in Antillia, while the Portuguese colony of Brazil on the Columbian continent is already several decades old by this point. But the Portuguese are friendly, and Brazil is far away, so I'm not going to begrudge them that. As for France, well, they're happily messing around rather uselessly with Africa.

- - - - - - - -

Next update is likely tomorrow, although if I can get it in later today I will.

Edward VI

Born: 3 February 1478, Aberhonddu, Wales

Married: [1] Elisabeth de Cornouaille (on 18 January 1496) [2] Eleanore Percy (on 4 September 1504)

Died: 17 May 1521, London

Born: 3 February 1478, Aberhonddu, Wales

Married: [1] Elisabeth de Cornouaille (on 18 January 1496) [2] Eleanore Percy (on 4 September 1504)

Died: 17 May 1521, London

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

King of England, Wales, Scotland, [Ireland and France]

Prince of Wales

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duke of Buckingham, Holland and Friesland, Cornwall, [Iceland and Bretagne]

Earl of Stafford, Count of Guines

Section I: England and Europe

By first appearance the accession of a younger and more energetic king, in the prime of his life, ought to have injected a boost into England. Unfortunately, the king the country got was Edward, a less-than-skilled man who suffered from a poor marriage. In 1496, when he finally reached his majority, he was wedded to Elisabeth, eldest daughter of Edward IV. Politically, it was incredibly useful by transferring the Cornwallist claim into the Stafford line. The problems that came with it, however, were numerous.

First, the marriage was consanguineous, the two being first cousins. This could be waved off and the marriage allowed to continue, but it would provide fodder for criticism not only of Edward and Elisabeth, but of Edward's children as well. Second, Elisabeth was considerably older than Edward, which was a threefold problem in and of itself. The wait between her majority and her marriage was unusually long for a woman of the time, and to the people of the time, the idea that she would manage to remain a virgin for a decade was considered ludicrous. Also, Edward hated being married to someone so much older; Henry ought to have known better, Edward thought, having suffered the same fate himself. Finally, Elisabeth was to emotionally dominate her husband during his time as Prince of Wales, which would have a permanent and negative effect on Edward.

Elisabeth of Cornwall, daughter, niece, sister, cousin, wife, and mother to kings.

Elisabeth herself never became Queen of England. Only a few months before her father-in-law/uncle Henry, on 11 February 1503, she died in childbirth. She had given Edward one son (Henry) and one daughter (Elisabeth), along with the child (Catherine) who died the same day as her mother. Although free of his wife's domination, however, he still relied on the Privy Council to do his work for him. Personally, he became the pawn of his mother, Catherine, who had scandalously remarried, to a knight named Sir Richard Wingfield, in 1505.

With his court either falling apart around him or managing to control him, Edward got almost nothing of note done at the beginning of his reign. He merely allowed the reforms his father had put into place to stay as they were; try as they might, the measures' opponents could never get past Catherine's iron will. About the only real event of his early reign was a war by Poland, France, and England against Pommerania. That German duchy had taken Oldenburg, and the Privy Council saw an opportunity to expand Friesland.

The army of the Duchy of Holland reached the city of Oldenburg on 30 December 1504. That winter wasn't too bad, but it was a double-edged sword: While the English army could move forward with little trouble, so had the city built up large food stocks to hold out. Throughout 1505 the siege dragged on; the leader of the expedition, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk (son of the John Norfolk killed at Richmond; he was with his father at the battle), insisted the army stay through the next winter. This time it struck with full force, hitting the army worse than the city. Only the arrival of another army in January of 1506 and some much-needed supplies prevented them from leaving, and finally, on 12 June 1506, the city fell.

It was a disaster for the inhabitants; the army, angry at the long wait, lusted for blood. A city which, like Oldenburg, surrendered rather than fell to attack was entitled to certain rights, but the soldiers were unconcerned about that: they wanted revenge. It began that night, as the English army settled into the town, ordered not to cause trouble. What incident sparked things was unknown; whatever it was, Norfolk came over to investigate. When he chastised his soldiers for their actions, they turned on him and shot him dead.

Within minutes the whole city was ablaze, the gates were locked, and a general slaughter ensued. Estimates are that more than three-fourths of Oldenburg's around 2500 inhabitants--men, women, and children alike--were killed outright, and most of the rest only survived by luck. The army had committed numerous crimes: treason, disobediance to orders, and mass murder. An Anglo-French army came to bring them in, dragging the war against Pommerania to a halt, and when most of the offending soldiers gave up, justice could be handed out.

Those who didn't surrender, about five hundred, were quickly captured and hanged. Another few hundred were immediately identified as especially at fault and joined in that fate. Two nobles who had taken part in the event were stripped of their lands and titles and exiled. As for the rest, they fell upon each other with innumerable accusations, and the English authorities did the best they could. Such actions by an army were an embarassment and scandal as had not been seen for centuries in Europe. The burnt shell of Oldenburg was given to the Duchy of Holland and Friesland in treaty a year later, and after a Count of Oldenburg was appointed the city could begin to recover.

With foreign affairs dealt with (if not correctly), the country's domestic situation became a concern again. Specifically, the country was going through the important period of the Inclosure Movement. This was not a national policy but a trend amongst the landowners, which picked up steam in the early 16th century. Before, much of the land was held privately but used in common, either given for different purposes when crops were not being grown, or rented out piecemeal to smaller farmers. Inclosure changed all this, causing increased privatisation of fields.

The Gleaners, by Jean-Francois Millet, 1857.

The cause for all this was the wool trade. Sheep farming had become increasingly popular, and the owners of the sheep wanted to take over the lands and convert farms to grazing areas. In this they were successful. The side effects came quickly: The conversion of farmland to sheep grazing caused higher rents and foot shortages, while the flood of displaced workers into the cities brought a number of problems, including overcrowding and crime. In 1509 there was a revolt in the Midlands, and only the intervention of the English army ended it.

Soon after, a rising star appeared in the English court. This was Thomas Wolsey, a Suffolk priest who had become Edward's Royal Chaplain. In this position he quickly gained the King's confidence, and rose to considerable power. Appointed Grand Almoner in 1509, he was now in the Privy Council and thus had the king's ear in more than one way. Through Wolsey, Edward proceeded to break everyone else's power and place the churchman in practical power over England. By 1515, he became Cardinal Wolsey and the Chancellor of England.

Thomas Cardinal Wolsey

Under Wolsey's administration, England began to prosper. Despite the continuing problems of Inclosure, agriculture boomed; trade with Europe was picking up, improving the economy not only of England but of Holland as well; and in 1510 Wolsey worked with Edward to begin the Cardinal College at Oxford, which would eventually become Christ Church College, Oxford. Wolsey also worked to begin negotiations with the Irish lords in an attempt to restore their loyalty; much money was spent, but little progress was seen in Edward's or Wolsey's lifetime. One of his most spectacular achievments was the preparations for the "Field of Cloth of Gold", a specacular event which unfortunately Edward did not live to see.

The end of Edward's reign was mostly of little note, mostly consisting of events elsewhere. Both Russia and Italy were struck by civil war; the former was an unsuccessful attempt by Prince Andrei of Staritsa, brother of Ivan III, to take the throne. The latter was an all-out free-for-all by the Italian nobility which destroyed the kingdom and led to the creation of a number of small states in the peninsula. Most notable in Germany was the statements of Martin Luther, a Saxon monk whose religious statements would soon divide Europe. In fact, Protestantism began to appear in England already; when a few London merchants began stating sympathy for Luther, they were condemned by the clergy of the city. Notably, Edward intervened on their behalf, refusing to allow prosecution. This foothold would play a major role in later English history.

Edward is definitely NOT Henry VIII. He resembles his namesake far more. I spent a summer at Christ Church, so Wolsey has always had a special place in my heart, glad he worked his way in here.

Edward was one of the most pathetic kings you have had during the whole game (CK part included). Hopefully his successor is stronger ruler.

Cardinal Petrus would be better in his work than Cardinal Wolsey, you can bet

Well, this king is not quite good. But I wonder if he can be worse...

Well, this king is not quite good. But I wonder if he can be worse...

Meh. Could have been a worse king.

But you better get colonising soon. Colonies make powers into superpowers.

But you better get colonising soon. Colonies make powers into superpowers.

And so, the reformation begins! Lets hope that someone decent is running the country...

For such a bad king, there's a refreshing and fortunate amount of mediocrity in his reign. It could have been so much worse for England and the House of Stafford. Let's keep our fingers crossed and hope that this will be the worst ruler England has to endure during its lifetime.

Spreading of heresies is a difficult thing, especially now the king has offered some tacit support to the movement. I wonder how these alternative beliefs will influence England.

Any news from the lands Cabot discovered?

Spreading of heresies is a difficult thing, especially now the king has offered some tacit support to the movement. I wonder how these alternative beliefs will influence England.

Any news from the lands Cabot discovered?

JimboIX: Yeah, when I made the switch I just kept the stats, so Edward ended up on the bad end of things. Fortunately, he's not too bad administratively, as you'll see in the next update...

canonized: You'll see. Religion's going to be a huge mess... and I've copied the "dynamic Reformation" events from the AGCEEP, which will only make things even more fun.

Olaus Petrus: Considering that England has had such rulers as Osric III and Renaud on its throne, that's saying a lot. We're not finished with Eddy, but Henry III will be an important ruler...

We're not finished with Eddy, but Henry III will be an important ruler...

Kurt_Steiner: Unfortunately, I would not want to distract His Eminence from reading my AAR by sticking him in it.

RGB: Oh I've been colonizing the whole time. I just figured to split the events of Europe and the Americas into two updates, since there was no better way to do it.

Sir Humphrey: Depends upon your opinion of what he ends up doing. The effects of Luther will resonate throughout English history, though, and often in a bad way.

TeeWee: The news of the American continent is the next update, actually.

canonized: You'll see. Religion's going to be a huge mess... and I've copied the "dynamic Reformation" events from the AGCEEP, which will only make things even more fun.

Olaus Petrus: Considering that England has had such rulers as Osric III and Renaud on its throne, that's saying a lot.

Kurt_Steiner: Unfortunately, I would not want to distract His Eminence from reading my AAR by sticking him in it.

RGB: Oh I've been colonizing the whole time. I just figured to split the events of Europe and the Americas into two updates, since there was no better way to do it.

Sir Humphrey: Depends upon your opinion of what he ends up doing. The effects of Luther will resonate throughout English history, though, and often in a bad way.

TeeWee: The news of the American continent is the next update, actually.

Section II: America

For most of Edward's reign, the events of the Americas were dominated by a single man: Ethelred Harcourt, up to 1502 an unimportant cavalry officer in the garrison of Calais. Harcourt was born sometime in the 1490s; the sources do not agree on his place of birth, some saying that he was born in Calais itself, others pointing to Southampton or Dover. The most likely place (as it appears in three otherwise unconnected accounts) is the Channel port of Hastings.*

On 24 August 1502, Harcourt approached the commander of the garrison, the Duke of Norfolk (the same one whose murder would spark the sack of Oldenburg), asking for permission to outfit an expedition to the New World. Norfolk agreed, although Harcourt apparently scraped up some of the money involved. Norfolk quickly obtained a royal grant to whatever land could be settled south of Long Island. By 4 October, Harcourt was sailing out of the port of Calais at the head of 500 adventurers, all cavalry, looking to make a name and/or fortunate for themselves in America.

It took until 10 April to complete the stormy crossing of the North Atlantic, with all of the ships and most of the men intact. Harcourt decided to boldly strike out into the wilderness to the west of the colony, two thousand Massachuset tribesmen following closely. Unfortunately, on 28 July he ran across a tribe considerably less friendly than the Massachuset: the Naragansetts.

Unhappy to have a strange group of men on even stranger beasts suddenly pop out of the forest, they decided the best way to deal with them would be to drive them away. The Massachuset fared no better, despite speaking the same language they were unable to speak sense into the angry Naragansett. The group quickly went back into English territory, where a colonial guard convinced the now-outnumbered natives to turn back.

19th-century engraving of a Naragansett demaning an Englishman leave his land.

Harcourt, unfazed, simply found some guns (early matchlock pistols, unreliable but good enough to scare the natives) and went back in. The guns made the difference, and Harcourt's men simply walked on, thinking every other problem would be this easy to deal with. What they found at the next place astounded them: Upon reaching the island of Manhattan on 6 November, they found a small city.

Small must be emphasized here; it was even smaller than Oldenburg, and would barely be a town today. But to a group of people expecting to find just another village of huts huddled in the wooded wilderness, it was very unexpected. What they discovered after that was another shock: After a Massachuset who was capable of speaking the language of these people was found, they soon were told that the town was part of a loose confederation which had enough cohesion to be considered a proper state.

This was the Iroquois (a name given to them by the French several centuries later; their proper name was and still is the Haudenosaunee), a band of five tribes who had expanded their influence to the coast. Once the amazement had worn off, Harcourt had enough sense about him to attempt to establish diplomatic contact. The town of Manhattan thus now housed an embassy of the King of England.

Statue of Hiawatha, legendary 12th century co-founder of the Iroquois, with his wife Minnehaha

Although relations were vaguely friendly, however, the Iroquois demanded that Harcourt not move through their lands. Such prevented any move to the south from there, causing the cavalryman to simply begin marching up the river (now known as the Hudson River after an early 17th-century figure of the region). By 23 May 1504 Harcourt had returned to Boston.

He quickly decided to get around the Iroquois problem by using the sea. On 17 August he found the location he had been looking for: a place to put a colony worthy of his patron's name. Through the winter preparations were made, contact was established with a local Powhatan chief, and on 9 February 1505, 100 men officially created the colony of Norfolk at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay.

A sketch of the original Fort Norfolk, from 1608.

For the next two years Harcourt worked on administrative matters in the colony, slowly seeing it grow with people from Britain. On 13 March 1507 he became satisfied with the colony's growth--a detailed recounting of which is sadly too much for this history--and looked to see what else could be found in the region. He began southward; what he found was the Dismal Swamp, a very well-named marshland that Harcourt hated enough to give such a name. Continuing along the coastline proved no more useful, and when he came to a river--now the Roanoke--he saw no sense in crossing it and simply marched up along it.

For the rest of the year he continued to explore the area, running at several locations into Iroquois territory. He soon discovered that they controlled a quite sizeable territory.** He returned to the town of Norfolk, only to find that the man he had named it after had been killed. Norfolk's son had sold the grant to the Duke of Lothian, James Borcalan, who thus renamed the region to "New Lothian", the name much of it retains today. Harcourt, for his part, had had enough of the swamps of the region and wanted to try northward.

Lothian gave him his chance, and after a wait of five years Harcourt found himself heading north. The King insisted that up to the river Cabot named after St. John--what is now the Grand Manan River--the land would be a part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony; however, the Duke of Lothian was allowed to create a new colony in the peninsula of (fittingly enough) Nova Scotia.

Harcourt came to the land in 1513, intent on building a new colony. He found a good harbour and created the town of Port Royal, hoping that it would be a great success. The problem was, the natives of the region, the Micmac, were no more friendly than the Naragansett, and on 7 June 1513 the town was burned. Harcourt was furious; collecting a little less than a thousand cavalrymen, he set out to find a Micmac town and burn it as well.

He found one on the banks of the Musquodoboit River, along with an approximately equal number of his enemy. Only two hundred stood at the riverbank where he first struck on 27 June 1513, and they were easily scattered. However, when the cavalry rode up the thin forest road, they were soon stopped by a prepared line of spearmen and archers. Even with their lower technology level they were able to hold their own for a while.

The English made a series of charges and withdrawls, slowly pushing their opponents back. Finally, they managed to find more open ground, and rushing around the enemy flank, wrapped them up and surrounded them. The Micmacs fought to the last man, and when Harcourt turned to destroy their village it was deserted, everyone else having moved on. All that was burned was the empty shells of huts.

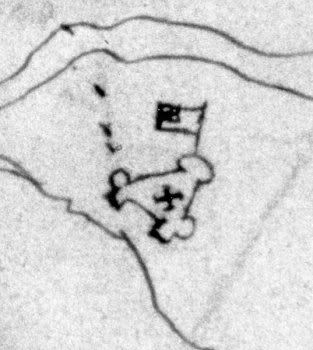

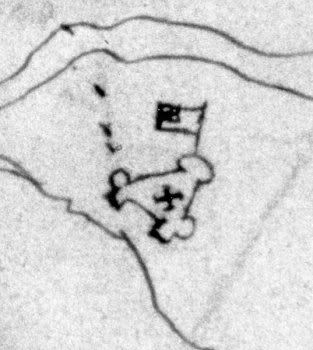

The Battle of the Musquodoboit. Each line is c. 100 men.

Harcourt himself succumbed to the Micmac Wars, assassinated by an enraged band of natives on 24 August 1514. The English eventually succeeded in either killing or driving the Micmac off; the tribe would remain in modern Acadia*** for more than a century afterwards. The town of Port Royal would be reestablished, but eventually overtaken by the later establishment of Halifax.

The travels of Ethelred Harcourt (click to expand)

- - - - - - - -

Edward VI had become quite sickly, and throughout the last decade of his life his poor governance was made worse by illness. Finally, on 17 May 1521, Edward died, succeeded by his son Henry. Said son would have many important policies, but one decision, a very personal one, would shock Europe and change English history forever.

__________

*The town is otherwise mostly unremarkable; the only other event of note was a minor battle in 1066 between the usurper Harold Godwinesson (who died there) and the also-usurper William of Normandy (who also died there).

**Corresponding to what is now New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and the northern parts of Maryland and Delaware.

***Our New Brunswick

For most of Edward's reign, the events of the Americas were dominated by a single man: Ethelred Harcourt, up to 1502 an unimportant cavalry officer in the garrison of Calais. Harcourt was born sometime in the 1490s; the sources do not agree on his place of birth, some saying that he was born in Calais itself, others pointing to Southampton or Dover. The most likely place (as it appears in three otherwise unconnected accounts) is the Channel port of Hastings.*

On 24 August 1502, Harcourt approached the commander of the garrison, the Duke of Norfolk (the same one whose murder would spark the sack of Oldenburg), asking for permission to outfit an expedition to the New World. Norfolk agreed, although Harcourt apparently scraped up some of the money involved. Norfolk quickly obtained a royal grant to whatever land could be settled south of Long Island. By 4 October, Harcourt was sailing out of the port of Calais at the head of 500 adventurers, all cavalry, looking to make a name and/or fortunate for themselves in America.

It took until 10 April to complete the stormy crossing of the North Atlantic, with all of the ships and most of the men intact. Harcourt decided to boldly strike out into the wilderness to the west of the colony, two thousand Massachuset tribesmen following closely. Unfortunately, on 28 July he ran across a tribe considerably less friendly than the Massachuset: the Naragansetts.

Unhappy to have a strange group of men on even stranger beasts suddenly pop out of the forest, they decided the best way to deal with them would be to drive them away. The Massachuset fared no better, despite speaking the same language they were unable to speak sense into the angry Naragansett. The group quickly went back into English territory, where a colonial guard convinced the now-outnumbered natives to turn back.

19th-century engraving of a Naragansett demaning an Englishman leave his land.

Harcourt, unfazed, simply found some guns (early matchlock pistols, unreliable but good enough to scare the natives) and went back in. The guns made the difference, and Harcourt's men simply walked on, thinking every other problem would be this easy to deal with. What they found at the next place astounded them: Upon reaching the island of Manhattan on 6 November, they found a small city.

Small must be emphasized here; it was even smaller than Oldenburg, and would barely be a town today. But to a group of people expecting to find just another village of huts huddled in the wooded wilderness, it was very unexpected. What they discovered after that was another shock: After a Massachuset who was capable of speaking the language of these people was found, they soon were told that the town was part of a loose confederation which had enough cohesion to be considered a proper state.

This was the Iroquois (a name given to them by the French several centuries later; their proper name was and still is the Haudenosaunee), a band of five tribes who had expanded their influence to the coast. Once the amazement had worn off, Harcourt had enough sense about him to attempt to establish diplomatic contact. The town of Manhattan thus now housed an embassy of the King of England.

Statue of Hiawatha, legendary 12th century co-founder of the Iroquois, with his wife Minnehaha

Although relations were vaguely friendly, however, the Iroquois demanded that Harcourt not move through their lands. Such prevented any move to the south from there, causing the cavalryman to simply begin marching up the river (now known as the Hudson River after an early 17th-century figure of the region). By 23 May 1504 Harcourt had returned to Boston.

He quickly decided to get around the Iroquois problem by using the sea. On 17 August he found the location he had been looking for: a place to put a colony worthy of his patron's name. Through the winter preparations were made, contact was established with a local Powhatan chief, and on 9 February 1505, 100 men officially created the colony of Norfolk at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay.

A sketch of the original Fort Norfolk, from 1608.

For the next two years Harcourt worked on administrative matters in the colony, slowly seeing it grow with people from Britain. On 13 March 1507 he became satisfied with the colony's growth--a detailed recounting of which is sadly too much for this history--and looked to see what else could be found in the region. He began southward; what he found was the Dismal Swamp, a very well-named marshland that Harcourt hated enough to give such a name. Continuing along the coastline proved no more useful, and when he came to a river--now the Roanoke--he saw no sense in crossing it and simply marched up along it.

For the rest of the year he continued to explore the area, running at several locations into Iroquois territory. He soon discovered that they controlled a quite sizeable territory.** He returned to the town of Norfolk, only to find that the man he had named it after had been killed. Norfolk's son had sold the grant to the Duke of Lothian, James Borcalan, who thus renamed the region to "New Lothian", the name much of it retains today. Harcourt, for his part, had had enough of the swamps of the region and wanted to try northward.

Lothian gave him his chance, and after a wait of five years Harcourt found himself heading north. The King insisted that up to the river Cabot named after St. John--what is now the Grand Manan River--the land would be a part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony; however, the Duke of Lothian was allowed to create a new colony in the peninsula of (fittingly enough) Nova Scotia.

Harcourt came to the land in 1513, intent on building a new colony. He found a good harbour and created the town of Port Royal, hoping that it would be a great success. The problem was, the natives of the region, the Micmac, were no more friendly than the Naragansett, and on 7 June 1513 the town was burned. Harcourt was furious; collecting a little less than a thousand cavalrymen, he set out to find a Micmac town and burn it as well.

He found one on the banks of the Musquodoboit River, along with an approximately equal number of his enemy. Only two hundred stood at the riverbank where he first struck on 27 June 1513, and they were easily scattered. However, when the cavalry rode up the thin forest road, they were soon stopped by a prepared line of spearmen and archers. Even with their lower technology level they were able to hold their own for a while.

The English made a series of charges and withdrawls, slowly pushing their opponents back. Finally, they managed to find more open ground, and rushing around the enemy flank, wrapped them up and surrounded them. The Micmacs fought to the last man, and when Harcourt turned to destroy their village it was deserted, everyone else having moved on. All that was burned was the empty shells of huts.

The Battle of the Musquodoboit. Each line is c. 100 men.

Harcourt himself succumbed to the Micmac Wars, assassinated by an enraged band of natives on 24 August 1514. The English eventually succeeded in either killing or driving the Micmac off; the tribe would remain in modern Acadia*** for more than a century afterwards. The town of Port Royal would be reestablished, but eventually overtaken by the later establishment of Halifax.

The travels of Ethelred Harcourt (click to expand)

- - - - - - - -

Edward VI had become quite sickly, and throughout the last decade of his life his poor governance was made worse by illness. Finally, on 17 May 1521, Edward died, succeeded by his son Henry. Said son would have many important policies, but one decision, a very personal one, would shock Europe and change English history forever.

__________

*The town is otherwise mostly unremarkable; the only other event of note was a minor battle in 1066 between the usurper Harold Godwinesson (who died there) and the also-usurper William of Normandy (who also died there).

**Corresponding to what is now New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and the northern parts of Maryland and Delaware.

***Our New Brunswick

Judas Maccabeus said:Edward VI had become quite sickly, and throughout the last decade of his life his poor governance was made worse by illness. Finally, on 17 May 1521, Edward died, succeeded by his son Henry. Said son would have many important policies, but one decision, a very personal one, would shock Europe and change English history forever.

This sounds promising... Would a woman with six fingers in one hand have something to do with it?

I just love reading about Ethelred in the new world, it's what makes this AAR so great. Especially his birth at Hastings, which is otherwise unremarkable..

Those natives sure seem intent on keeping the English at bay. Such tenacity!

Great work with this AAR. Love the references to our timeline counterparts and their (in)significance

Great work with this AAR. Love the references to our timeline counterparts and their (in)significance

I'm still in awe of your battles, they bring the story to life like nothing else.  Bravo...

Bravo...