Throughout the course of history, the human race has tried to protect itself against the recurrent war by

building appropriate defence systems and fortifications as well. The inhabitants of the territories who were

threatened by enemies have sought refuge behind walls, trenches, and entrenchments. But it needs to be

stated that the associated construction of the Styrian city fortifications did not rest on a general need of pro-

tection. The construction concerned had mainly been a targeted response of the inhabitants to the threat

which the land was facing as described above. A settlement surrounded by walls always served as a symbol

of defence and safety. That is why the Styrian cities such as Bruck an der Mur, Fürstenfeld, Hartberg, Juden-

burg, Leoben, Marburg / Maribor, Rann / Brežice, Pettau / Ptuj, Radkersburg, and last but not least Graz had

already been surrounded by fortifications since the 13th/14th century. Initially, such fortifications consisted of

relatively weak curtain walls with semi-circular towers and city gates. But later on – during the 16th century – ,

things changed fundamentally. The construction of strong fortifications in the Italian-style was considered to

be a reaction to the offensive weapons which had become more and more powerful.

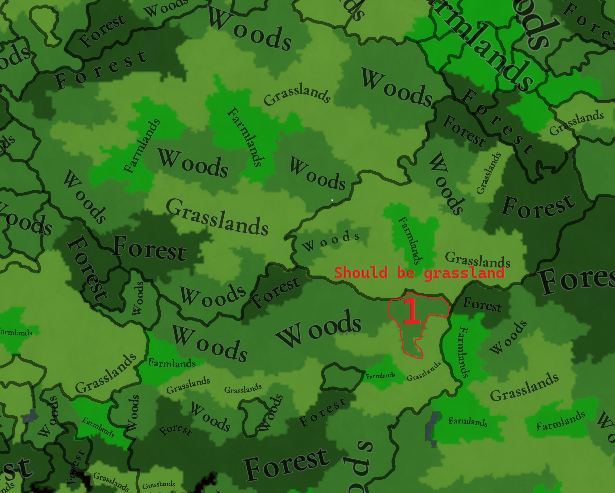

And so it came to pass, that since the middle of the 16th century the medieval walls were replaced by trenches,

curtain walls, bastions, casemates, and gate-towers in the important cities of Fürstenfeld, Marburg / Maribor and

Radkersburg. (Image 1) Such a course of events had also taken place in the city of Graz since the year of 1544.1

1 About the development of fortifications in Graz see TOIFL, L. 2003, pp. 450–600. About the Development of fortifications in Radk-

ersburg, Fürstenfeld, Rann / Brežice, Pettau / Ptuj und Marburg / Maribor see the paper from Mrs VREČA, B. in the present volume.

Image 1: The castle of Maribor,

copper engraving by Georg Mat-

thäus Vischer, 1678

14

However, with regard to a proper territorial defence people did not solely rely on the fortified cities and

castles. Due to the medieval conception of legality authorities tried to obligate all able-bodied men for

military service. But reality has shown that, due to economic reasons alone, it was impossible to draft all

inhabitants of the land into military service at the same time. Especially from the peasants a participation

in military campaigns across the borders of the country and lasting for several weeks, could not have been

demanded. Otherwise the crops would not been harvested and the food supply would have collapsed.

Based on this recognition, a principle emerged in the course of the Late Middle Ages which stated that

economically dispensable subjects of a territorial lord only had to achieve military services. However, even in

this connection the Styrian margraves and – since 1180 – dukes, could initially demand unrestricted military

service solely from their own subjects and ministerials. Nevertheless, the High Middle Ages have already

forestalled something which became relevant for the organisation of the territorial defence in the late 15th

century under the nomination Gült. It was already in the 12th and 13th centuries, when the manpower of the

aristocrats liable to the enlistment of (their) men had depended on the size of their estates. At this point it

needs to be stated that the richer ministeriales were obliged to provide a higher number of mounted soldiers

to military service than those who were less affluent.² In the course of the Middle Ages, the number of these

men was kept within reasonable limits due to the relatively low population density of the land during that

time. But during the prime time of the territorial defence in the period during the 16th and 18th centuries,

things were completely different. With a better personal positioning of the Styrian ministerials since the

High Middle Ages, the principles of imperative allegiance to the duke were becoming increasingly weak; a

timely limited military service had been reached gradually. Finally, the service was limited to a few weeks

per year and ultimately strictly amounting to the defence of Styria. The aforementioned limitation forced the

Habsburgs, who started to rule over Styria in the year of 1282, to use recruited contingents of knights in order

to achieve the military enforcement of their European dynastic politic. By this way armies formed by knights

dominated the numerous battle fields in Europe during the whole High Middle Ages. It was not until the 14th

century, that a change of the military tactics took place. From then on people’s levies were increasingly being

put into use, both in Austria and in Styria. Such mass levies fought on foot, carried on the wings of national

enthusiasm, following the example of the Old Swiss Confederacy and the Hussite troops in Bohemia.³

A strictly organised territorial defence for Styria started in 1443 out from a defence regulation, which was been

directed against Hungarian mercenaries: three captains and the inhabitants of the northern part of East Styria had

to hinder the intrusion of Hungarian troops into Styria. Because this did not guarantee sufficient protection for the

whole land, a second defence regulation was issued in the year of 1445 that radically extended the conscription to

war service. The parishes were earmarked as an organizational basis, whereby several parishes were united into

defence districts. By this way, Styria had been divided into 22 smaller districts which were presided over by a total

of 75 aristocratic captains. In addition to that, all aristocratic and clerical landowners, as well as cities, and market

towns were obliged to send every tenth man to military service. Cities and market towns were urged to set up

weapon- and ammunition depots, as well as food storages in order to supply the participants in the campaigns.⁴

The defence regulations from the years 1443 and 1445 came into existence at a joint instigation of the Styrian

estates land and duke Frederick III. The same applied to the third defence regulation from the year of 1446.

The provisions of the aforementioned regulation had been closely aligned to its predecessors. The only, but

important, novelty was the fact that Carinthia and Carniola, which were under the Habsburg rule as well,

promised to send soldiers for the defence of the borders of Styria.

It was at the diet in Leibnitz in the year of 1462 when the Styrian estates had acted entirely independent in

relation to the defence of Styria for the first time. A defence regulation, in German language Defensionsor-

dnung, had been approved without the consent Frederick III, who had become emperor in the meantime.

According to this new defence regulation Styria was divided into four districts (later there were five) and

every household was obliged to pay taxes.⁵ Frederick III reacted disgruntled and even accused the Styrians

2 RUHRI, A. 1986b, p. 201.

3 RUHRI, A. 1986a, p. 155.

⁴ ROTHENBERG, I. 1924, pp. 14–42.

⁵ RUHRI, A. 1986a, p. 156.

15

of conspiracy. However, on the part of the emperor no sanctions were imposed. That is due to the fact that

Frederick was dependent on the estates concerning to the defence of the borders and peacekeeping. It was

Friederick’s son Maximilian I who endeavoured to take the reins from the Styrian estates with regard to the

territorial defence. In 1495 Maximilian I sought for a collaboration of all Habsburg hereditary lands. But

things were not crowned with success until the year of 1518 when the defence regulations called the Inns-

brucker Libell had been passed. The aforementioned regulations provided mutual military support between

the duchies Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, the archduchy of Austria below the river Enns (Lower Austria) and

Austria above the river Enns (Upper Austria) as well as joint financing of the mercenary troops, being hired in

order to protect the Habsburg hereditary lands.⁶

Nevertheless, during the course of the 16th century, the Styrians took a number of steps leading to specific

requirements of the Styrian defence, remaining valid for more than 200 years: the appointment of war councils

in the cases of concrete wartime situations,⁷ the installation of the permanent Graz court council of war

(Hofkriegsrat) in the year of 1578,⁸ the development of armouries, and the creation of a military border in

the territory of today’s Croatia. In the course of time, a phenomenon, later known as the »dualistic military

constitution«, emerged due to the fact that both, the Styrian estates and the ducal authorities largely acted

independently. The principle of the concerning constitution seemed to be simple: the current Styrian duke (and

also Emperor since 1619) as well as the Styrian estates were obliged to keep their own troops, to equip the

armouries, to provide provisions and, last but not least, to provide funding for all listed above. However, in cases

of emergency, a merging of either both system structures or with other words both armies, under the slogan:

»Organising separately, marching jointly« had been planned. The image of reality was much more miserable.

Both sides tried to influence each other, whereby the ducal authorities in particular exerted a great deal of

pressure on the estates, which were personified by the five representatives named the Verordneten. The main

demands were the payment for soldiers who were in garrison at the Slovene or Wendish military border, the

call-up of Styrian levies and the hiring out of military equipment to the ducal cities and market towns.9

Despite the constantly tense financial situation the Styrian estates vigorously carried on with the call-up of

levies, with organizing the taxation being necessary for the financing of the levies, as well as with the de-

velopment of the administrative machinery. The Styrian diet, consisting of representatives of the nobility,

clergy and citizens, became the deciding authority and was obliged to deliberate at least once a year. The

responsibility for the implementation of the resolutions concerning the territorial defence, which had been

passed, rested with the aforementioned diet. Decisions of the diet were carried out by an executive body

of the estates, which consisted of five members and had to be re-elected every year. They were named Ver-

ordnete and acted permanently since the year of 1527. (Image 2) In agreement with the ducal authorities

(Hofkriegsrat) the aforementioned Verordneten deployed the officers which were necessary for the cavalry

and the infantry of the levy, appointed a colonel (who then acted as the supreme commander), as well as the

captains and cavalry captains for the five military districts, into which Styria had been divided. The submis-

sion of candidate proposals for the officer positions on the military border, the acquisition of funds in order

to pay the soldiers and mercenaries, the compliance of fire signals (serving as a pre-warning system since the

year of 1557),10 effective military border post connection Graz – Maribor – Ptuj – Varaždin – Zagreb, as well

as the procurement of arms also counted amongst the duties of the Verordneten. The call-up respectively

financing of the levies presented the biggest problem for the Verordneten. In simple terms, the manorial

ownership of the landlords was the basis for the application of fighters or for the recruitment of mercenaries

to defend the country. Accordingly, each landowner was required to provide a rider or three foot soldiers for

war services per 100 pounds of annual income. An example: was the income between 500 and 600 pounds,

the landowner had to send either 5 horses and horsemen or 15 foot soldiers. The arms, which had been a

necessary part of the accoutrement for the subjects, could have been borrowed or purchased from the Sty-

⁶ RUHRI, A. 1986b, p. 201.

7 StLA, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum XIV (Militaria), 1526 September 2 (201514/125).

⁸ StLA, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum XIV (Militaria), 1578 s.d. (201514/6015); SCHULZE, W. 1973, p. 73 f.

9 Cf. the extensive documentary material in the Styrian Archives (StLA), Laa. Archiv, Antiquum XIV (Militaria).

10 Steirische Kreidfeuerordnung ddo 1557 Mai 15: StLA, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum XIV (Militaria), Slipcase Kreidfeuer (1530–1594). About

the fire signal system itself cf. ROTH, A. 1986, p. 219 f.

16

rian armoury (Landeszeughaus) by the landlords. Landowners with an annual income of less than 100 pounds

were not required to send any soldiers, but they were obliged to pay a special tax which was known under

the name Wartgeld. These earnings enabled the estates to finance additional horsemen or foot soldiers for

the levy. Additionally the inhabitants of the Sovereign`s cities and market towns were also obliged to pay

special taxes for the recruiting of mercenaries. Despite all efforts, the military power of the country was not

fully exploited in such a way. That is why, starting from the year of 1522, additional levies in form of the fifth

and tenth man had also been called up in cases of need. This means that 20 percent or 10 percent of subjects

from each landlord were called to arms.11 However, due to the fact that the increasing vigour of firearms

made the military importance of such people’s levies insignificant, battle-tried mercenaries were recruited

instead since 1530. Due to high costs, this had presented an undertaking which could not be realised in a

long run. That is the reason why the Styrian estates returned to the form of exclusive people’s levies, but also

applied stronger measures which concerned the selection of the conscripts. This lead to the emergence of

an elite unit: a levy consisting of 2,000 to 2,500 men called the Levy of the Thirtieth Man, well-known as the

contingent of marksmen since 1556. This contingent too was recruited according to the principle of the Gült:

for each 100 pounds of income a landlord had to send three marksmen. Things remained that way all until

the year of 1594.12 It was only in times of great enemy threat when the levy of the Fifth- and Tenth Man had

been called up additionally. In some cases the aforementioned levies were convened with recruited foreign

mercenaries. An essential change in the organisation of the Styrian levy took place in the year of 1631. It was

from that year on that the levies were no longer called-up and mustered every year as hitherto, but only in

extreme cases of enemy threat.13

Mounted harquebusiers and heavy cavalrists, representing levies funded on the basis of the landlord`s annual

income, participated in the territorial defence parallel to the contingents of the infantry levy. Per 100 pounds

11 SCHULZE, W. 1973, pp. 113–117.

12 RUHRI, A. 1986b, p. 201 f.

13 StLA, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum V, Slipcase 174 (Alte Zeughausakten), Slipcase 15 (1631–1680).

Image 2: The Verordneten in the early 18th cen-

tury. Detail of a copper engraving by Ignaz Flurer.

In: Georg Jacob von Deyerlsperg, Erbhuldigungs-

werk für Kaiser Karl VI., 1728

17

of annual income, a landlord had to send one horseman (or three foot soldiers) to the levy. But it was left

up to the landlords to raise the horses and horsemen either by themselves or to entrust a reliable person in

providing the horsemen. It was not until the year of 1629 that the institution of the constant cavalry had been

abandoned. But, when needed, salaried cavalry units were recruited instead.14

In an ideal situation, the levy consisted of a combination of heavy cavalry, lightly armed harquebusiers,

marksmen and halberdiers. (Image 3) However, the protection of the land very often rested on levies consist-

ing solely of foot soldiers or cavalry. The quantitative extent of a levy depended on the degree of the enemy

threat and for how many of the five districts of the country the call-up was valid. Based on a general call-up

the Verordneten determined the number of the levy participants, appointed supreme commanders, defined

the numerical ratio of fighter-types to one another, and fixed the deployment date.15 Then, the levy partici-

pants were obliged to come fully equipped to gathering places which had been previously determined. There

they were tested for their war suitability in a special military check. It was only in cases of emergency that the

banns marched from the military inspection directly to the theatre of war. Normally they were sent return

to their homes.16

14 PICHLER, F. 1986, p. 237 f.; TOIFL, L. 2005, pp. 25–27.

15 TOIFL, L. 2005, p. 25.

16 StLA, Patente und Kurrenden: 1522 Februar 26 Graz.

17 About the military inspections cf. the numerous inspection registers in the StLA, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum V, Slipcase

Musterregister (mostly existing for every year in the 16th century).

Image 3: Mannequins of

participants in a Styrian levy,

around 1590. Group of fig-

ures in the former exhibi-

tion Zum Schutz des Landes

(1997–2012) in the Landes-

zeughaus Graz, Universalmu-

seum Joanneum (Photograph

by Niki Lackner)

The fact that the levy had been raised every year until the twenties of the 17th century did not automatically

mean that the men were sent on a mission. The purpose of such assemblies primarily lied in the capability

assessment of the soldiers to be. It is for this purpose that Styria had organised annual military inspections.

(Image 4) Commissioners visited all five districts in order to record the subjects who were able to serve as

foot soldiers or horsemen in registers. It is in these registers where one can often read that only very few

noblemen were willing to despatch well-equipped subjects.17 The reason for that was the noblemen’s fear

of very high costs and apparently peasant uprisings as well. Sometimes it even happened that subjects with

physical disabilities were sent to the military inspections. The commissioners then furiously noted words

in the registers like: »has a bent back«, »is stupid«, »is blind«. It happened quite often that persons to be

checked failed to appear at the military inspections, for which various excuses have been given. Even high

fines could not make a difference in their way of thinking.

18

Image 4: Military inspection,

end of the 16th century. Wood-

cut in Kriegsbuch des Leon-

hard Fronsperger, 1596

The depicted structures of the Styrian defence remained in use until the early 18th century. But then, due to

the course of strong centralisation endeavours the hitherto independent Styrian warefare fell evermore under

the supremacy of the imperial authorities in Vienna. In the year of 1704 the soldiers of a Styrian levy suffered

a horrible defeat against Hungarian rebels. The surviving men were incorporated into the imperial army. In the

later 18th century they found themselves on various battlefields of Europe.18 Even the Styrian armoury which

had also been independent up to that point and was responsible to provide arms exclusively for the territorial

levy and the military border, turned more and more into a supply basis intended for the needs of the imperial

army. In the year of 1749 the armoury should have been dissolved completely.19 But it survived.

In the course of the 18th century the hitherto war apparatus of the Styrian dukes like the court war council

(Hofkriegsrat), the court chamber (which had acted as a revenue), as well as the court armoury in Graz also

passed under the guardianship of the Viennese central authorities and were finally dissolved. They were

followed by a number of institutions under the control of Vienna like the General Command, the National

Military Command or the Army Corps command.20 All of them performed tasks of exclusively administrative

character only and were restricted to the territory of Inner Austria, namely Styria, Carinthia and Carniola.

Important orders were given from Vienna. With the collapse of Austria – Hungary at the end of World War I

the Styrian warfare passed away definitively.

18 BRAMREITER, P. 1982, p. 67.

19 KRENN, P. 1962, pp. 146–148.

20 BRAMREITER, P. 1982, pp. 71–83; EGGER, R. 1982, p. 21.

19

SOURCES AND LITERATURE

SOURCES

StLA, Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv Graz, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum XIV (Militaria), 1526 September 2

(201514/125).

StLA, Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv Graz, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum XIV (Militaria), 1578 s.d. (201514/6015).

StLA, Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv Graz, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum XIV (Militaria), Slipcase Kreidfeuer (1530–

1594), Steirische Kreidfeuerordnung ddo 1557 Mai 15.

StLA, Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv Graz, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum V, Slipcase 174 (Alte Zeughausakten), Slipcase

15 (1631–1680).

StLA, Patente und Kurrenden: 1522 Februar 26 Graz.

StLA, Laa. Archiv, Antiquum V, Slipcase Musterregister.

LITERATURE

BRAMREITER, P. 1982, Peter Bramreiter, Die höchste Militärbehörde in Graz 1701–1918, in: Graz als Garni-

son, Publication series of the City Museum Graz, Volume III, Graz, 1982, pp. 66–85.

EGGER, R. 1982, Rainer Egger, Graz als Festung und Garnison, in: Graz als Garnison, Publication series of the

City Museum Graz, volume III, Graz, 1982, pp. 9–47.

KRENN, P. 1969, Peter Krenn, Zur Geschichte des Steiermärkischen Landeszeughauses in Graz, in: 150 Jahre

Landesmuseum Joanneum, Joannea, volume II, Graz, 1969, pp. 141–171.

PICHLER, F. 1986, Franz Pichler, Die steuerliche Belastung der steirischen Bevölkerung durch die Landesde-

fension gegen die Türken, in: Die Steiermark, Brücke und Bollwerk, Katalog zur steirischen Landesausstellung

1986, Graz, 1986, pp. 236–238.

ROTH, F. O., 1986, Franz Otto Roth, Versuchte »Frühwarnung« vor Türkeneinfällen in die Steiermark, in: Die

Steiermark, Brücke und Bollwerk, Katalog zur steirischen Landesausstellung 1986, Graz, 1986, pp. 219–222.

ROTHENBERG, I. 1924, Ignaz Rothenberg, Die steirischen Wehrordnungen des 15. Jahrhunderts, in: Zeitschrift

des Historischen Vereines für Steiermark, Number 20 (1924), Graz, 1924, pp. 14–42.

RUHRI, A. 1986a, Alois Ruhri, Landesverteidigungsreformen im 15. Jahrhundert, in: Die Steiermark, Brücke

und Bollwerk, Katalog zur Steirischen Landesausstellung 1986, Graz, 1986, pp. 155–156.

RUHRI, A. 1986b, Alois Ruhri, Neue Wege der Heeresaufbringung in der Steiermark: Gültrüstung zu Pferd und

Büchsenschützen, in: Die Steiermark, Brücke und Bollwerk, Katalog zur Steirischen Landesausstellung 1986,

Graz, 1986, pp. 201–202.

SCHULZE, W. 1973, Winfried Schulze, Landesdefension und Staatsbildung, Studium zum Kriegswesen des

innerösterreichischen Territorialstaates 1564–1619, Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für Neuere Ge-

schichte, volume 60, Wien-Graz-Köln, 1973.

TOIFL, L. 2003, Leopold Toifl, Stadtbefestigung – Wehrwesen – Krieg, in: Brunner Walter (ed.), Geschichte der

Stadt Graz, Band 1: Lebensraum – Stadt – Verwaltung, Graz, 2003, pp. 450–600.

TOIFL, L. 2005, Leopold Toifl, Zum Schutz des Landes, Katalog zur Dauerausstellung in der Kanonenhalle des

Landeszeughauses Graz, Graz, 2005.