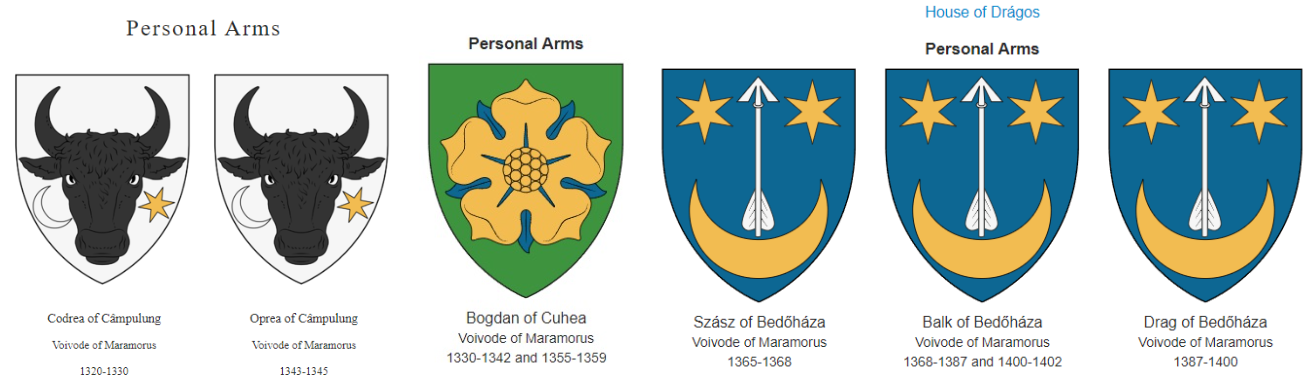

I'm currently exploring how and in what numbers could further pastorialists (tribesmen?) be added. 300 families on Mount Athos seems like an extreme claim though. Could it be possible that the text actually refers to all of the Chalkidiki Peninsula? I will try to look into where does this claim originates from, maybe that could help to clarify things.

France had a quite notable pastorialist population in its more mountainous areas, AFAIK.

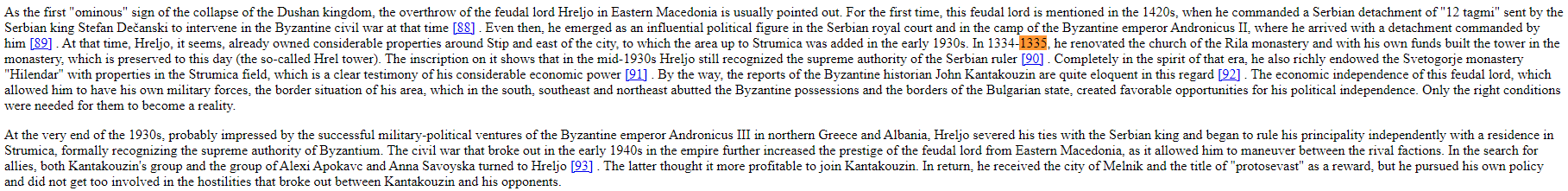

That's right, but where did Dragoș come from? It could be argued that he came from Moldavia, although there's no definite proof of it. Still, it can be speculated that the Vlachs of Máramaros and vicinity came from Moldavia, not from the South directly. This can be inferred by the difference in their societal structures. Knezes in the area headed much smaller communities compared to their Southern-derived counterparts (a few families at most), and it were the voivodes who united these kneziates into broader communities comparable to the Southern Kneziates.

Hungary wasn't an area dominated by nomads either, not in the past 300 years from the start date at least.

It could be argued that Dragoș was native of Maramures.

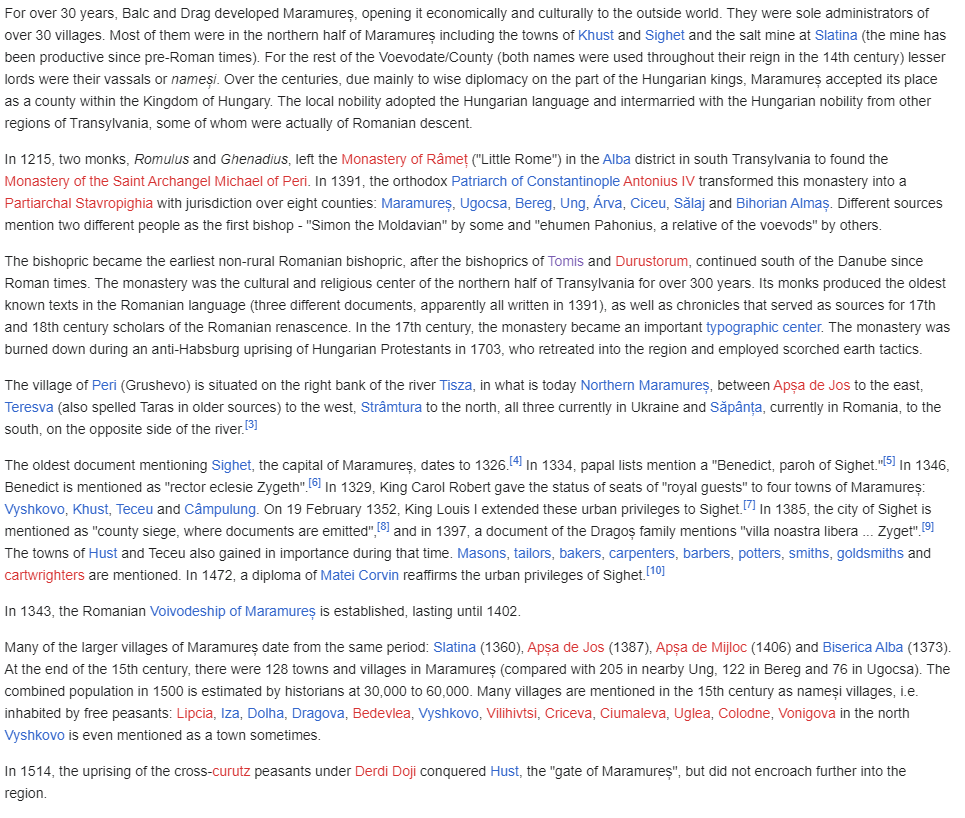

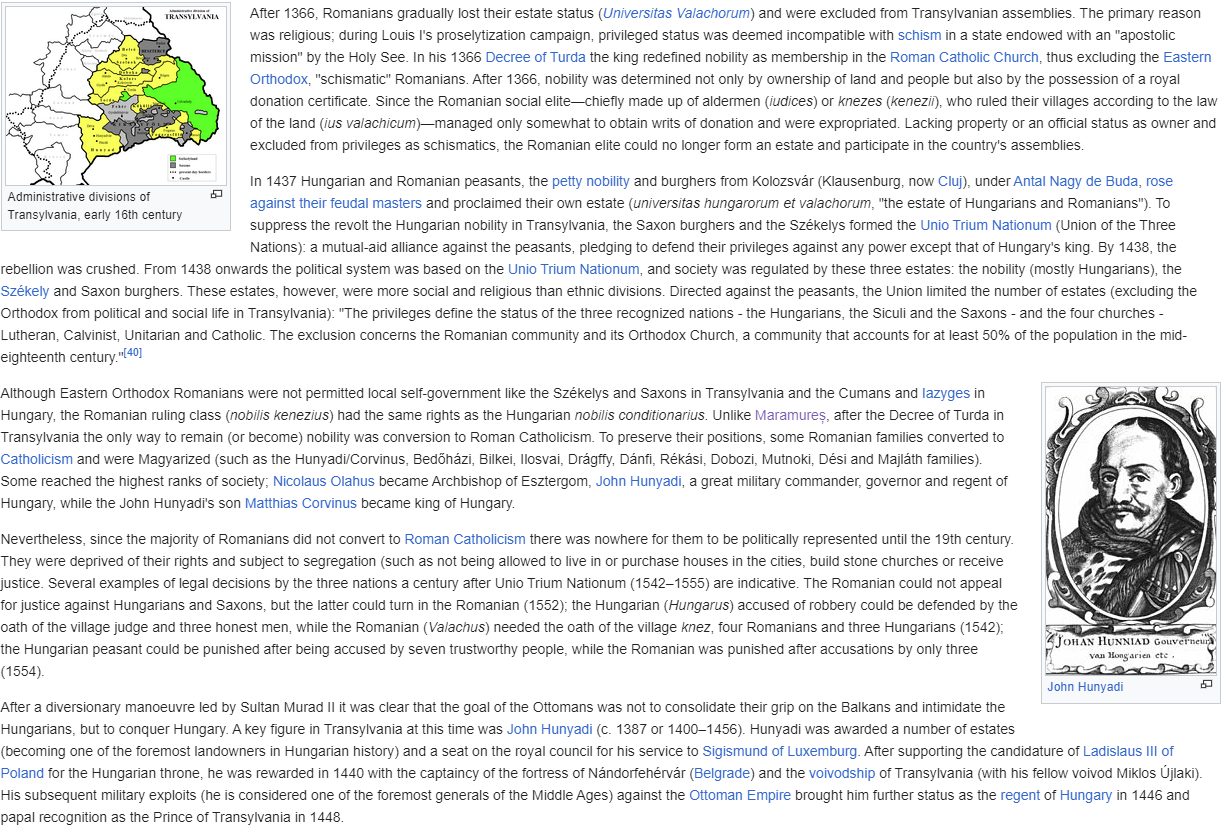

Bedohaza is actually the house of Dragos. They decided to convert to Catholisicm and magyarize after the Romanian nobility lost rights in Transylvania.

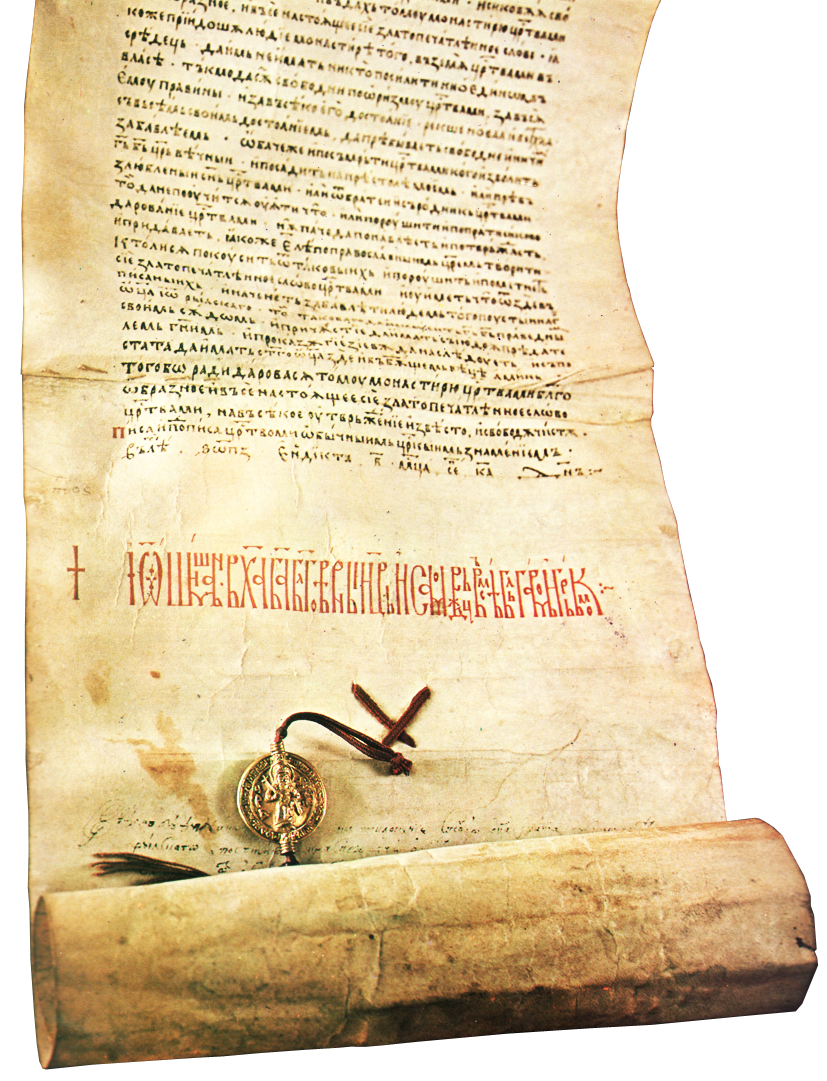

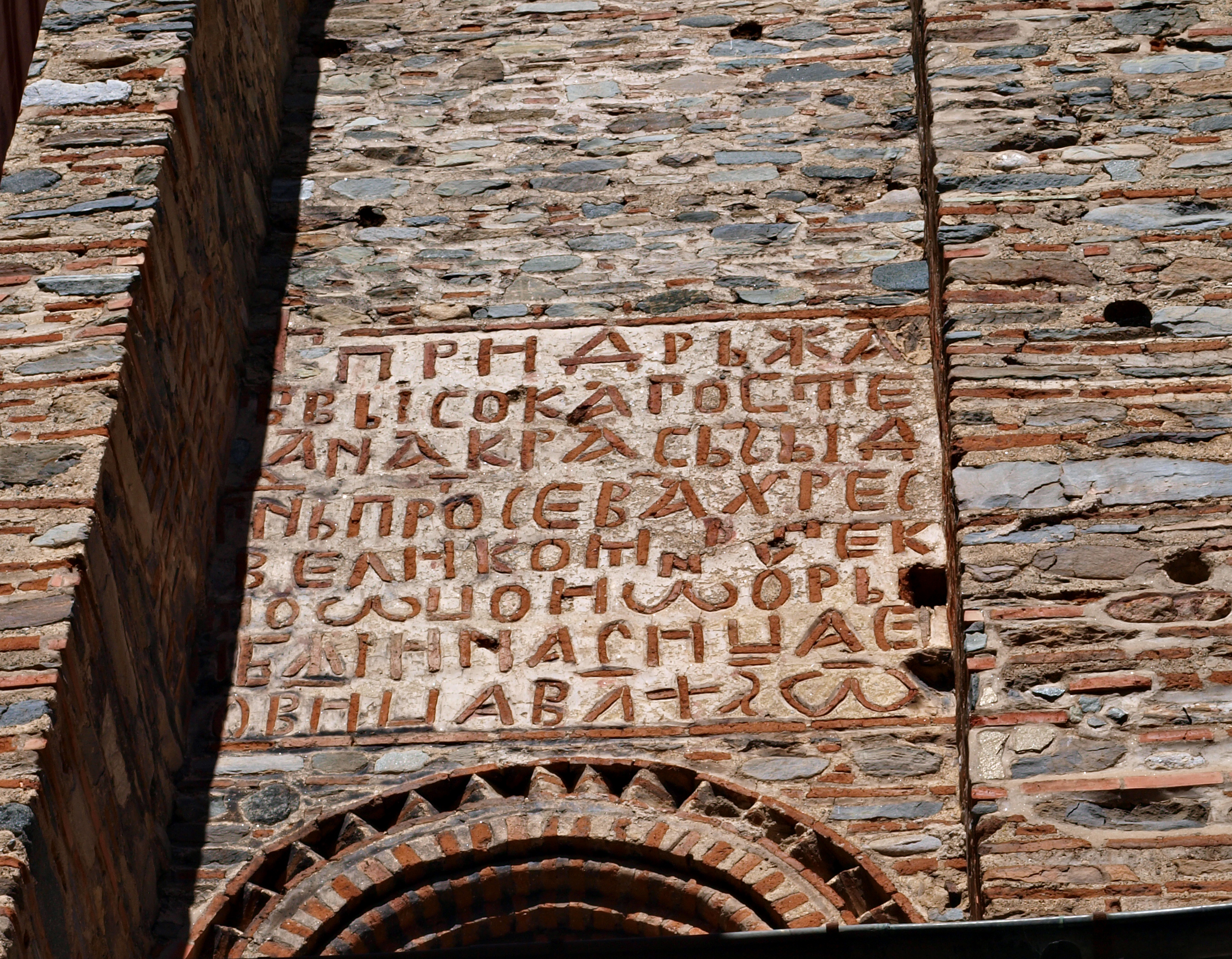

see:

(such as the Hunyadi/Corvinus, Bedohazi)

That's not what I meant, the vacuum was in the North. Vlachs were long present in the area of Wallachia (and likely also Moldavia) by the point of the nomadic retreat. Some of them were pastorialists and some of them settled. It was the waning of the nomadic presence that allowed more of the population to pursue a settled lifestyle though (the pop. vacuum I was referring to). With the retreat of the nomadic elements, the cultural make-up of the area also became more homogenous, allowing the Romanians to be the sole dominant ethnic group here, assimilating whoever else also remained (like groups of Jassics and also Slavs). In Moldavia, there were notably more Slavs and other groups, so things weren't so clear-cut there. I don't have an estimate of my own for the population size of Wallachia, but the devs didn't make the area particularly populous either, which could be attributed to the demographic process mentioned above still being in relative infancy. This also relates to how the Romanian/Vlach population didn't yet represent such large part of the population of (Eastern) Hungary as it later on did.

We do not know that. There is no direct written evidence of a large-scale Romanian (Vlach) migration into Transylvania during the medieval period, while contemporaries in the 1200 do not regard the Romanian (Vlach) as migrators. In fact, they almost unanimously say that that the Romanian (Vlach) are the leftovers from the Roman Empire.

Is there was indeed a large-scale Romanian (Vlach) migration into Transylvania, wouldn't it be reasonable to assume that at least 1 chronicler would mention that? Instead we have works such as the Russian Chronicle that says the opposite.

According to Jean W. Sedlar, the oldest extent documents from Transylvania, dating from the 12th and 13th centuries, make passing references to both Hungarians and Romanian Vlachs.

Meaning the oldest documents from Transylvania, make reference to both Hungarians and Romanians. There are no earlier documents for the Romanians in Transylvania because there are no earlier documents for the Hungarians in Transylvania as well.

Also according to Jean W. Sedlar, it cannot be ascertained from any extant documentary evidence how many Vlachs (Romanians) may have resided in Transylvania in the 11th century. The actual number of persons belonging to nationalities is at best guesswork, the Vlachs may have comprised 66% of Transylvania's population in 1241 on the eve of the Mongol invasion.

As settled lifestyle and farming spread in relation to the local nomadic decline, it began to deny access to more and more lands from the pastorialists, which was the catalyst for their search for more lands. The Mongol devastation of Hungary also needs to be considered. It dealt a huge blow to the country's own internal demographic strength (to colonise/populate peripheral areas), and that together with the late Árpádian decline of royal power removed prior existing barriers to Vlach migration.

Coming up with some form of estimation for pastorialist populations invisible to state administration could probably help in this regard, but by this point we actually really are on the field of pure speculation. As I wrote previously, we did also consider charters and other contemporary primary sources when we assigned pops, after all. Still, if we could find a good referal point for how many pastorialists could be housed by xy square kilometer, then that could put us on a path of progress, I suppose. The Mount Athos figure could become this referal point, maybe, but its source and credibility needs to be verified first.

We're not talking about only an initial seeding population. The rise of the Romanian, Ruthenian and Serb population was in large part driven by continous immigration to the areas in question. Aside from Southern Transylvania, the appearance of the Vlachs was a very recent phenomenon in regards to the start date. The first mention of Vlachs in Fehér County is a charter from the 1290s, for example. Kristó's previously mentioned book describes this process well.

Also, if start date would be just twenty or thirty years later, we would already need to count with a notably higher Romanian presence at quite a few places, like Máramaros for example.

We already need to count a notably higher Romanian presence in Maramures.

And regarding the first mention of Vlachs in Fehér County (Fagaras), is not a charter from the 1290s.

A royal charter from 1223 mentions that the land where the Carta monastery was founded was taken from the Vlachs (Romanians). The said monastery was finished in 1202. This implies that the Vlachs (Romanians) lived there, and the Hungarian authorities confiscated their lands and eventually built Carta monastery there who was finished in 1202.

Similar charters mentioning land taken from the Romanians exist for Zarand in 1318, Bihor in 1326 and Turda from 1342.

Regarding Vlach population in Transylvania:

There is evidence of Romanians in Transylvania but scarce.

According to Jean W. Sedlar, the oldest extant documents from Transylvania, dating from the 12th and 13th centuries, make passing references to both Hungarians and Romanian Vlachs.

In 1213, an army of Romanian Vlachs, Saxons and Pechenegs, led by the Count of Sibiu, Joachim Türje, attacked the Second Bulgarian Empire - Bulgarians and Cumans in the fortress of Vidin. After this, all Hungarian battles in the Carpathian region were supported by Romance-speaking soldiers from Transylvania.

A royal charter from 1223 mentions that Cârța Monastery in Transylvania founded on the lands taken from the Romanians. Cârța Monastery was finished in 1202.

Similar charters mentioning land taken from the Romanians exist for Zarand in 1318, Bihor in 1326 and Turda from 1342.

According to the Diploma Andreanum issued by King Andrew II of Hungary in 1224, the Transylvanian Saxons were entitled to use certain forests together with the Vlachs and Pechenegs.

However, the debate over the population and ethnic composition of Transylvania during the period between 800 and 1300 is a deeply contentious issue in both Romanian and Hungarian historiographies.

This debate is critical because it shapes the historical narratives surrounding the origins of modern Romania and Hungary, as well as the region's medieval political landscape. Both Romanian and Hungarian historians have produced extensive arguments regarding the presence and role of their respective populations Romanians and Hungarians during this period, often drawing on different primary sources and archaeological evidence to support their claims.

Romanian Historiography: Continuity Theory.

Romanian historiography emphasizes the concept of Daco-Roman continuity, arguing that Romanians are the descendants of the Romanized Dacians who remained in the Carpathian-Danubian region after the withdrawal of the Roman Empire in the early 3rd century AD. According to this view, the ancestors of the modern Romanians inhabited the region continuously from Roman times through the early Middle Ages, including the period between 800 and 1300. Mainly based on medieval sources, who almost unanimously regard the ancestors of the Vlachs as Roman colonists settled in Dacia Traiana. or sources although scarce who mention Vlachs north of the Danube in what would become Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania.

The most famous or infamous, but not the only one, is "Gesta Hungarorum" by Anonymous: One of the most cited sources by Romanian historians is Gesta Hungarorum (The Deeds of the Hungarians), written in the late 12th century by an anonymous Hungarian chronicler. This chronicle describes the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin around 895 and includes references to various local populations encountered by the Hungarians, including the Vlachs. Romanian historians argue that these mentions of Vlachs indicate the continuous presence of a Romanized population in Transylvania before and during the Hungarian conquest. The anonymous chronicler refers to Gelou, a "Vlach" leader, the duke of Transylvania, who resisted the Hungarian invasion in the 9th century. This is often cited as evidence of a pre-existing Romanian population. Meanwhile Hungarian histography regards Gesta Hungarorum as unreliable described as far as "a work of fiction".

Notitia Dignitatum and Roman Military Influence: Romanian historians point to administrative and military continuity in the region. Although the Roman Empire formally withdrew from Dacia in 271 AD, the presence of the Notitia Dignitatum, a 5th-century Roman administrative document, suggests that Roman military influence continued to persist in the region for some time. Romanian scholars interpret this as evidence that Romanized populations, particularly in the mountain valleys, maintained their presence well into the Middle Ages.

Archaeological Evidence: Romanian historians also rely on archaeological findings, such as cemeteries, pottery, and ecclesiastical structures, which they argue show continuity between Roman Dacia and medieval Transylvania. For instance, Christian artifacts found in certain parts of Transylvania are interpreted as evidence of a Romanized and Christianized population that persisted through the early Middle Ages.

Hungarian Historiography: Migration Theory.

Hungarian historiography, on the other hand, largely rejects the notion of a significant Romanian Vlach presence in Transylvania prior to the Hungarian conquest in the late 9th century. Hungarian scholars argue that the region was sparsely populated before the arrival of the Magyars and that the development of Transylvania as a political entity occurred primarily under Hungarian rule. This perspective is grounded in the idea that the region's medieval population was primarily formed through Hungarian colonization, along with the settlement of other ethnic groups such as Saxons and Szeklers. With the Romanians only arriving later and gradually as migrators in the late 12th to 14th centuries.

"Gesta Hungarorum" Reinterpretation: While Gesta Hungarorum is also a crucial source for Hungarian historiography, Hungarian historians often reinterpret the reference to the Vlach ruler Gelou. They argue that either Gelou and his people were not necessarily representative of a widespread and well-established Romanian population in Transylvania, but rather a small, isolated community, or that Anonymous’ descriptions are either exaggerated or symbolic, meant to emphasize the military prowess of the Hungarian conquerors, and do not reflect the actual demographic situation in Transylvania at the time of the conquest.

"Chronicon Pictum": The Chronicon Pictum, a 14th-century Hungarian illuminated chronicle, also provides key details regarding Hungarian expansion. It contains fewer references to the Vlachs than the Gesta Hungarorum, and Hungarian historians emphasize this as indicative of the lack of a substantial Romanized population in Transylvania during the early medieval period. They suggest that if there had been a large, organized Vlach presence, it would have been noted more explicitly in this chronicle.

Papal and Diplomatic Records: Hungarian scholars frequently refer to medieval papal records and royal charters, which document the settlement and organization of Transylvania under Hungarian rule. These sources, dating from the 11th century onwards, record the settlement of various ethnic groups, including Hungarians, Saxons, and Szeklers, but make little mention of Romanians. Hungarian historians argue that these early documents indicates that their presence in Transylvania was minimal or non-existent before this time. In Romanian histography this is not regarded as relevant as papal and diplomatic records were mainly interested in Catholics, and point to the fact that Pope Innocent VI preached a crusade "against all the inhabitants of Transylvania, Bosnia and Slavonia, which are heretics", reasoning that if Transylvania was heretical in the pope's view, a term which was also used for Orthodox people by Catholics, the region had an overwhelming non-Hungarian majority.

By the 12th and 13th centuries, both Romanian and Hungarian historiographies agree that Vlachs (Romanians) appear more frequently in historical records.

However, the two historiographies differ in their interpretations of this presence.

Romanian historians argue that the increased documentation of Vlachs during this period reflects their ongoing, ancient presence in Transylvania, which began to be more formally acknowledged as the political landscape of the region changed. For example, by the mid-13th century, papal documents mention Vlachs in connection with the Cuman presence in the eastern Carpathians and the Kingdom of Hungary.

There is no single piece of direct written evidence that conclusively demonstrates a continuous Romanian presence in Transylvania from the early medieval period through the 13th century. However, Romanian historians point to various indirect sources, such as mentions of Vlachs in chronicles, legal references, and papal documents, along with archaeological evidence, to support the argument for continuity.

Hungarian historians, on the other hand, argue that the emergence of Vlachs in historical records during this period reflects the migration of Romanian shepherds from the southern Balkans into Transylvania.

There is no direct written evidence of a large-scale Romanian (Vlach) migration into Transylvania during the medieval period, but various indirect references in chronicles, papal documents, and charters have been interpreted differently by Romanian and Hungarian historians. Most historical records on the population of Transylvania prior to the 13th century are sparse and often ambiguous, making it challenging to determine the exact nature and scale of any migration or population movements.

However, even Hungarian historiography acknowledges that there was likely a Romanian Vlach population at the time of the arrival of the Hungarians, but their numbers were insignificant, likely 5% to 20% of the population of Transylvania, depending on the historian. In order to explain away the scarce reference of Vlachs in Transylvania.

According to Hungarian and Romanian historiography, the lack of presence/uninterrupted presence of a Romanized population in Transylvania is proven by archaeological evidence.

According to Hungarian historiography, the presence of Slavs is confirmed by archaeology, but no distinctive trace of Romanians can be found in Transylvania at the time of the Hungarian conquest.

According to Romanian historiography, the presence of Slavs is questionable as the sudden disappearance of the Transylvanian Slavs cannot be explained, it is more likely that a considerable percentage were Romanians with their Slavic influences. The research of Transylvanian toponyms is a complex endeavour that could cause certain errors as the Hungarian and German toponyms are easier to distinguish while a Romanian toponym may as well be dismissed as a Latin or Slavic toponym due to Romanian being a Latin-based language with Slavic influences, being impossible to differentiate between toponyms made by the people speaking a certain language and toponyms created by another people such as the Romanians with foreign elements adopted from the Slavs, being essentially culturally a mix of Roman and Slavic it's impossible to find Romanian archaeological evidence that doesn't look either Slavic or Roman in nature. This is also true for the later centuries when we have confirmed Romanian archaeological evidence, that looks either Slavic or Roman.

While based on Dzaihani's accounts as to how the Hungarian chief would call to arms 20.000 warriors, in Hungarian historiography is estimated that the Hungarians amounted to 400.000-500.000 people and found 150.000-200.000 natives in Transylvania, as the effort of 4-5 families was necessary for maintaining 1 armed warrior, assuming there were about 5 individuals per family.

While according to Romanian historiography, these estimations are exaggerated and unlikely to be correct, as the Hungarians were a Steppe people where every able man was a warrior, and these estimations are not consistent with other accounts of the time, such as Genghis Khan's Mongolia being able to raise 129.000 men with a population of 800.000 people, the West Goths having a population of about 250.000 people and able to raise 70.000-80.000 men or Vandals and Alans who numbered 80.000 people and could have fielded an army of around 15.000–20.000 men.

In what small regions of Transylvania the Romanians clearly are mentioned in the 9th century?

The presence of Romanians (Vlachs) in Transylvania during the 9th century is mentioned in a few key sources, though the evidence is indirect and often open to interpretation. In general, written records from this period are sparse, but several sources provide references to Vlachs or related groups in specific regions of Transylvania.

1. The Region of Bihor -> Gesta Hungarorum (The Deeds of the Hungarians) One of the most cited references is found in the Gesta Hungarorum, written in the late 12th century by an anonymous chronicler. The Gesta describes the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin and mentions the Vlach leader Gelou, who is said to have ruled in the region of Bihor, which is located in western Transylvania. According to the chronicle, Gelou resisted the Hungarian invaders around the end of the 9th century. Although this account is written from a Hungarian perspective and its accuracy can be debated, it is often interpreted as evidence of a Vlach presence in this region during the late 9th century.

2. The Region of Mureș ->Early Hungarian Chronicles and Legal Documents References in early Hungarian chronicles and legal documents occasionally mention Vlachs in the Mureș River region, located in central Transylvania. These references often appear in the context of Hungarian expansion and settlement efforts. For instance, there are mentions of Vlach communities in the Mureș Valley, though these documents are not always dated to the 9th century specifically. The mention of these communities is used by some historians to argue for the presence of Vlachs in central Transylvania around this time.

3. The Southern Carpathians and the Făgăraș Mountains -> Byzantine and Western European Sources Although not as directly detailed as other regions, Byzantine sources and early Western European records sometimes refer to Vlach groups living in the broader Carpathian region, which includes parts of southern Transylvania such as the Făgăraș Mountains. These references are less specific but contribute to the broader understanding of Vlach presence in the Carpathian region.

4. The Eastern Carpathians -> Medieval Chronicles and Later Records Later medieval sources, such as the Hungarian chronicles from the 12th and 13th centuries, also refer to Vlachs in the eastern Carpathians, which includes areas of eastern Transylvania. These references often describe Vlachs living in the mountainous and pastoral regions, suggesting a presence that could date back to the 9th century, although the documentation from this earlier period is less specific.

Several primary sources, many of which are chronicles, legal codes, and papal documents—provide references to the Vlachs (the medieval term for Romanians) and their settlements.

1. Anonymus' Gesta Hungarorum (late 12th – early 13th century) -> This chronicle by a notary of the Hungarian king mentions the Vlachs (Romanians) living in Transylvania at the time of the Hungarian conquest in the 10th century. Though highly debated in terms of its accuracy, it is one of the earliest mentions of Romanians in Transylvania.

2. Diploma Andreanum (1224) -> A document issued by King Andrew II of Hungary granting privileges to the Saxon settlers in southern Transylvania. The document refers to the presence of Romanians (Vlachs) alongside the Hungarians and Szeklers in the region.

3. Papal Bull of Pope Innocent III (1204) -> A papal letter referring to the Christian population in the Balkans and parts of Hungary, including mentions of Vlach Christians in the Transylvanian area, recognizing their existence and influence in the region.

4. Regestrum Varadinense (13th century) -> This is a record of land disputes and legal issues involving nobles and local populations in Transylvania, including Romanians. The document sheds light on Romanian landowners and their interaction with the Hungarian nobility.

5. The Chronicle of the Priest of Dioclea (14th century) -> Although primarily focused on the history of the southern Slavs, this chronicle references the Vlachs in the Carpathian and Transylvanian regions, suggesting their presence in medieval Eastern Europe.

6. Carta of King Louis I of Hungary (1366) -> Issued by Louis I, this charter outlines laws applying to different ethnic groups in Transylvania, including the Romanians. It mentions "Romanian knezes" (local leaders), providing insight into their role in Transylvanian society.

7. Papal Bull of Pope Gregory IX (1234) -> This bull refers to the Cuman and Vlach populations in Transylvania and highlights the concerns of the Catholic Church about the Christianization of these communities. It gives evidence of their existence and prominence.

8. Chronicle of Thomas of Spalato (13th century) -> A Dalmatian cleric, Thomas of Spalato, mentions the Vlachs living in the Carpathian Basin, including Transylvania, in his accounts of the Hungarian Kingdom and its relations with neighboring peoples.

9. Moldavian and Wallachian Charters (14th–15th centuries) -. While primarily documents from the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, some charters reference migrations and connections of Romanian populations in Transylvania, suggesting ongoing cross-border interactions.

10. The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (1358) -> This chronicle describes the history of Hungary and mentions the various peoples in Transylvania, including the Vlachs. While it mainly focuses on Hungarian history, it offers glimpses into the ethnic composition of Transylvania in the medieval period.

11. Laws of Voivode Ladislaus Kán (early 14th century) -> Issued by the powerful Hungarian voivode of Transylvania, these laws refer to Romanian serfs and their obligations, providing legal context for the Romanian presence in the region.

12. The Russian Primary Chronicle (also known as the Tale of Bygone Years or Nestor's Chronicle; 1113) -> The chronicle mentions that the Hungarians passed through the land of the Volokhi (Vlachs) on their way to Pannonia. The chronicle mentions the Bulgars and the Vlachs in a broader context of conflicts in the Balkans and southeastern Europe. The Russian Primary Chronicle does not explicitly mention Transylvania by name. At the time the chronicle was written, Transylvania was not yet a well-defined political entity, however, the Russian Primary Chronicle does mention the Vlachs (referred to as "Volokhi" in Old Slavonic), which were a Romanized population in the broader Carpathian and Danubian regions, possibly including parts of what would later become Transylvania.

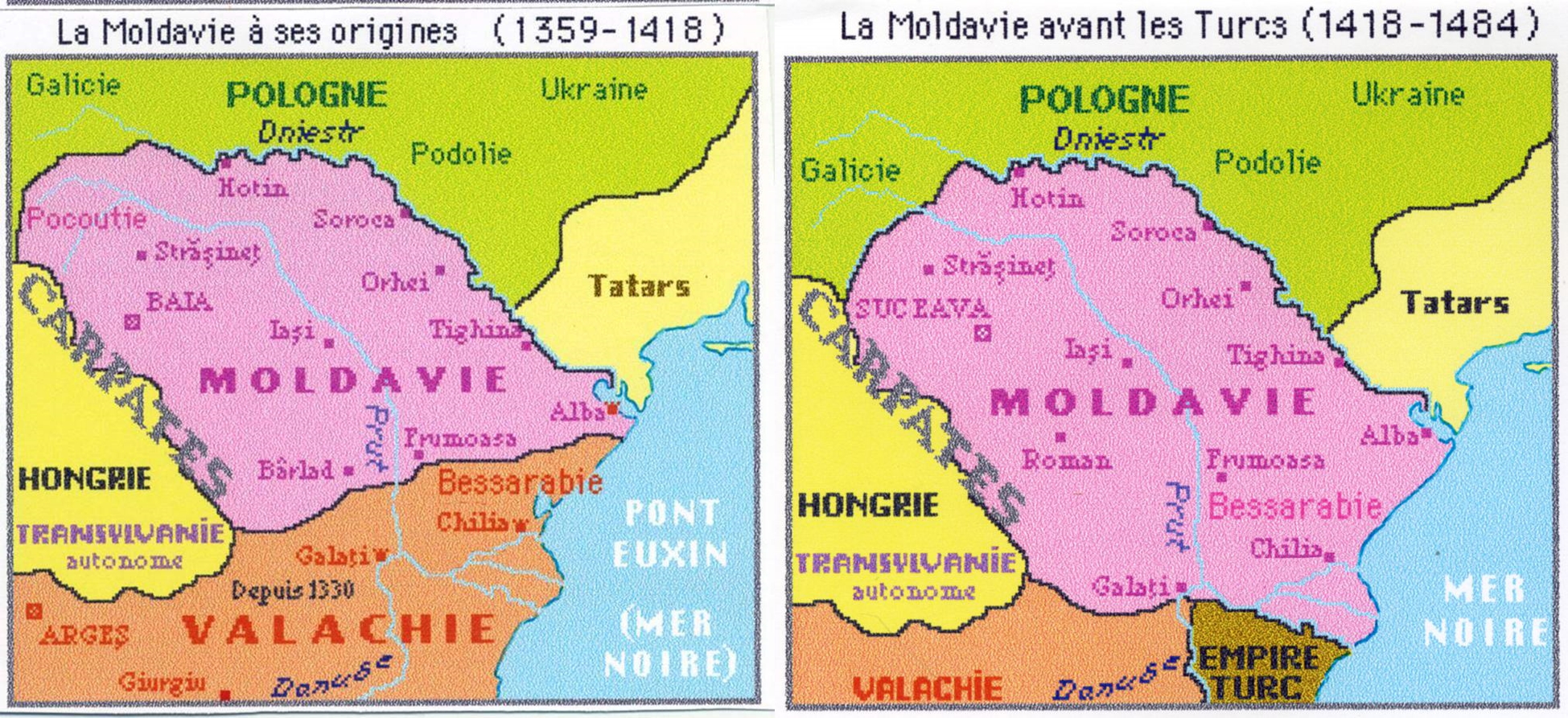

Regarding the Founding of Moldavia:

Moldova did not exist in 1337, but rather various vassal states of the Blue Horde, that would eventually be liberated from the Blue horde and united with Baia by a Hungarian military campaign over the Carpathians, who (the Hungarian king) placed Dragoș as their ruler (of the Moldavians).

Dragos would only control the Baia region, it was Bogdan who conquered/united the rest of Moldavia. The only thing we know is that 2 Vlach knezi (chieftains, like a count) opposed Bogdan and were defeated and their regions integrated by force, the others willingly became vassals of Bogdan. But we do not know their names or what territory which knez controlled. We only know of the name of one of them - Dimitrie - who ruled close to Cetatea Alba attested by a Hungarian diploma in 1368.

Before Dragoș arrived in what would become Moldavia, the region was a mix of unorganized territories, inhabited primarily by Romanians (Vlachs) but also by 1Slavs, Tatars, and other smaller groups. It was a frontier zone, lying between several powerful neighbors, such as the Kingdom of Hungary to the west, the Golden Horde to the east, and the Polish Kingdom to the north.

In those times (the 13th and early 14th centuries), Moldova was not yet a unified or structured state. Instead, it was made of loosely organized communities led by local Romanian knez (chieftains, like a count), but there was no central leadership or administrative organization. The region also had forests, hills, and rivers, which made it an ideal place for people seeking refuge from invasions or oppressive rulers elsewhere.

However, Moldova was vulnerable to external forces. The Tatars of the Golden Horde, a Mongol successor state, often raided the area, taking control of large parts of the region and forcing local populations to pay tribute. This left the local population under constant threat of invasion and domination.

At this time, the Hungarian crown was looking to expand its influence eastward. The area that would become Moldavia was strategically important, as it could serve as a buffer against the Tatars and other threats. The Hungarians sought to bring the region under their control, and this is where Dragoș came in.

Dragoș, a Romanian kneaz (like a count) from the northern region of Maramureș, held a position of trust under the Hungarian king, who was expanding his influence into neighboring lands. Dragoș was tasked by the king with an important mission: to secure the eastern region known as Moldova from the threat of Tatar invasions. In the early 1340s or 50s (no consensus), Dragoș led an expedition across the Carpathian Mountains into this largely unorganized territory, and after succeeding in his mission, he was appointed by the king as the voivode (military leader, like a duke, higher rank than kneaz) of Moldavia. However, Moldavia under Dragoș was still a vassal state, meaning it remained under Hungarian control.

Meanwhile, back in Maramureș, another powerful Romanian noble, Bogdan, also held the title of voivode (had a higher title than Dragoș, he was like the Duke of Maramures) and governed the area. Unlike Dragoș, Bogdan became increasingly defiant toward the Hungarian crown. Bogdan had long-standing disputes with the Hungarian authorities over autonomy and power in his homeland. When these conflicts reached their peak, Bogdan decided to leave Maramureș and seek a new opportunity.

In the 1350s or 60s (no consensus), Bogdan took action. Gathering his loyal supporters, he moved eastward into Moldavia, with the clear intention of freeing the region from Hungarian control. At that time, Moldavia was still ruled by Dragoș' nephew, who remained loyal to Hungary. Bogdan faced resistance from Dragoș' family, but after a series of battles and political maneuvers, Bogdan defeated them. By overthrowing Dragoș’ successors, Bogdan effectively ended Hungary's control over Moldavia and declared it an independent principality, making himself the ruler.

Once in power, Bogdan I (as he became known in Moldavian history) worked to consolidate his control over the region. He established Moldavia as a sovereign state, free from foreign dominance, and began organizing its political and military structures. He ruled Moldavia until his death in 1365, ensuring that his principality was strong and independent. After Bogdan’s death, his son, Lațcu, succeeded him as the next voivode of Moldavia. Under Lațcu’s leadership, Moldavia continued to grow as an independent state.

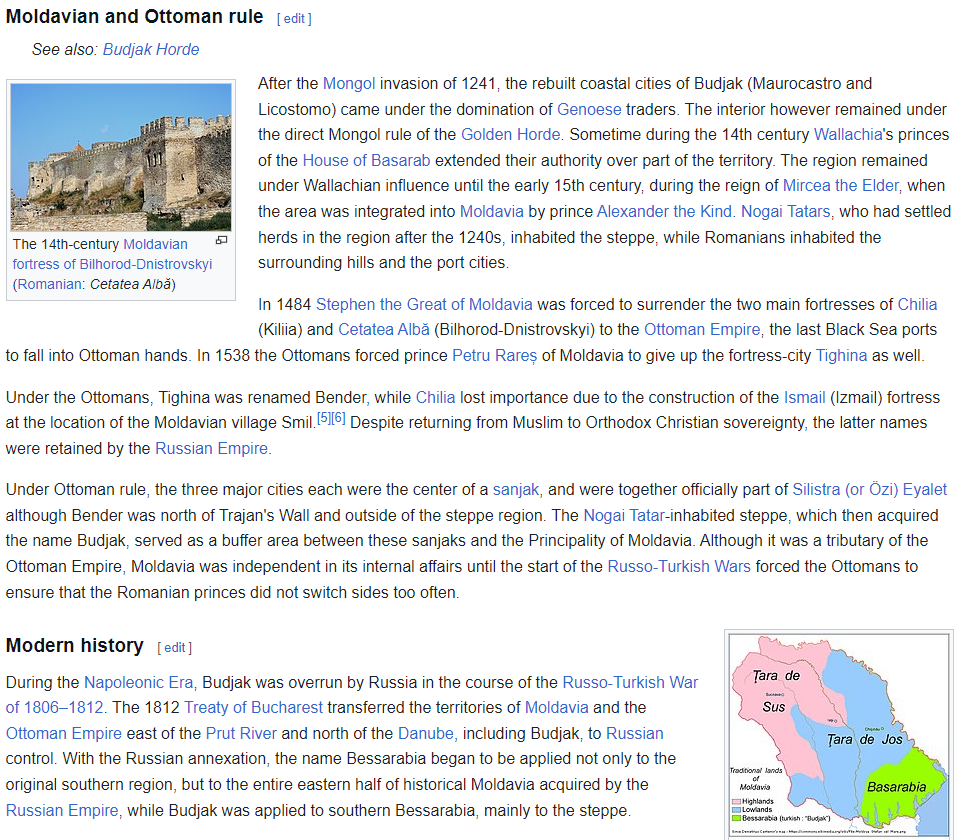

Regarding the region of Bessarabia/Budjak:

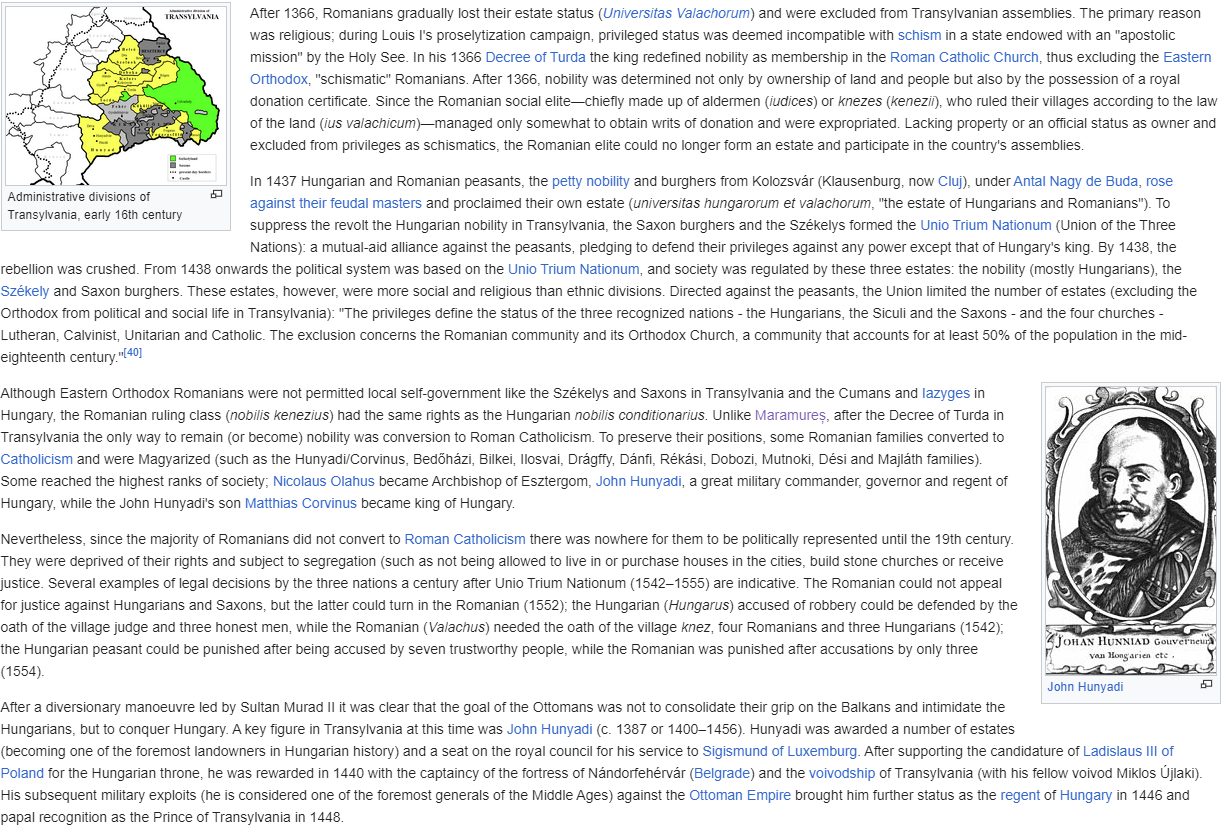

This week we’re posting the general map of the region, along with some more detailed maps, that can be seen if you click on the spoiler button. A starting comment is that the location density of Hungary is noticeably not very high; the reason is that it was one of the first European maps that we made, and we based it upon the historical counties. Therefore, I’m already saying in advance that this will be an area that we want to give more density when we do the review of the region; any help regarding that is welcome. Apart from that, you may notice on the more detailed maps that Crete appears in one, while not being present in the previous one; because of the zooming, the island will appear next week along with Cyprus, but I wanted to make an early sneak peek of the locations, given that is possible with this closer zoom level. Apart from that, I’m also saying in advance that we will make an important review of the Aegean Islands, so do not take them as a reference for anything, please.

This week we’re posting the general map of the region, along with some more detailed maps, that can be seen if you click on the spoiler button. A starting comment is that the location density of Hungary is noticeably not very high; the reason is that it was one of the first European maps that we made, and we based it upon the historical counties. Therefore, I’m already saying in advance that this will be an area that we want to give more density when we do the review of the region; any help regarding that is welcome. Apart from that, you may notice on the more detailed maps that Crete appears in one, while not being present in the previous one; because of the zooming, the island will appear next week along with Cyprus, but I wanted to make an early sneak peek of the locations, given that is possible with this closer zoom level. Apart from that, I’m also saying in advance that we will make an important review of the Aegean Islands, so do not take them as a reference for anything, please.

Country and location population (which I’ve also sub-divided, and is under the Spoiler button).

Country and location population (which I’ve also sub-divided, and is under the Spoiler button).