Echoes of A New Tomorrow: Life after Revolution in the Commonwealth of Britain

- Thread starter DensleyBlair

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Threadmarks

View all 115 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

1967 election: Press endorsements 1967 Election Results: 21:30 Thursday, May 4 1967 1967 Election Results: 07:00 Friday, May 5 1967 Make This Your Commonwealth: Lewis in coalition In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority (Part One: A History of 'Common Beat') In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority (Part Two: Red Autumn I) In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority (Part Two: Red Autumn II) In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority (Part Three: Red Autumn III)I can only imagine @El Pip reading that and sitting off crying in the corner banging on the wall.

- 3

- 1

Yes, preposterous really when you think about it!

Pip gave the message a stoic thumbs up reaction, which I’m sure masks all sorts of inner turmoil.I can only imagine @El Pip reading that and sitting off crying in the corner banging on the wall.

- 5

Honestly I'd have been more surprised if there had been anything positive at all. It would be like complaining that Threads was a bit bleak, the unrelenting awful misery and comprehensive crushing of anything good or hopeful is the point.Pip gave the message a stoic thumbs up reaction, which I’m sure masks all sorts of inner turmoil.

- 1

- 1

View attachment 1079106

Pip gave the message a stoic thumbs up reaction, which I’m sure masks all sorts of inner turmoil.

In his alt version of your alt version, Mosley tripped on the carpet and this changes EVERYTHING.

- 2

- 1

Indeed. Gerjaz Fritz rises to power through his mastery of carpet bonding, leading to the Anglo-Slovak Union ruling much of Europe.In his alt version of your alt version, Mosley tripped on the carpet and this changes EVERYTHING.

- 4

In fairness, this would’ve been gold dust for the Redadder writing room.In his alt version of your alt version, Mosley tripped on the carpet and this changes EVERYTHING.

May we see peace in our time!Indeed. Gerjaz Fritz rises to power through his mastery of carpet bonding, leading to the Anglo-Slovak Union ruling much of Europe.

- 4

Indeed. Gerjaz Fritz rises to power through his mastery of carpet bonding, leading to the Anglo-Slovak Union ruling much of Europe.

With hip flasks for all!

The days of T&T...good times*.

*Unless you are T&T, of course. Then "Good Times" is just an concept beyond the grasp of Slovakia.

Edit:

DensleyBlair, I meant to comment on your announcement about the next update earlier, but I ran out of time.

After spending some time today pushing ahead with the next chapter (or the next section of our current chapter), I have come to something of a profound realisation. Having been working on the Lewis-era material for over two and a half of Echoes' four-and-a-half-year lifespan, our upcoming chapter, at long last, will bring the arc to a close. The present plot lines (the mining dispute, economic liberalisation, Welsh autonomist militancy, the revived social movement, the breakdown of the traditional party political system, and so on) will all reach their (interim) conclusions with the end of the story of Lewis's premiership. Put another way, I will have finished telling the story that I was so excited to begin telling three years ago, when I first began to plan it in detail: the story of a society coming out of the long, hard years of Mosleyism and beginning, fitfully, and with great pain and difficulty, to shape for itself a new self-image. This being the case, I have decided that, with this as-neat-as-possible tying up of the present problems, the next update will be our last substantive chapter, and Echoes of a New Tomorrow will come to an end.

I am looking forward to seeing the end of this magnificent project. It has been a great ride, full of different ways of showing how your world has developed. The Redadder updates in particular were hilarious, and stood perfectly on their own if you knew nothing about the OTL influences (like me).

Well, for one thing, it does not mean the end of the Commonwealth. I'm not sure exactly how long I will keep writing the imagined history of this wonderful, dysfunctional world, but I've got sketches taking us one way or another all the way up to 1993. That is probably an upper limit, and I have no idea how realistic a prospect getting there is, but I am determined to do the Seventies at the very least.

I know what you mean. I have my current Presidents AAR sketched out to 1991, but I don't know if I will get that far either. After all, there is A LOT of things going on in the Sixties. In fact, I think I have spent more time on that decade than I did on the decades prior.

Last edited:

- 3

- 1

- 1

I just read your update on the Aberfan disaster. My dad remembered hearing about it when he was a boy. Such an awful tragedy. It was nonetheless very interesting to read about it within the context of your alternate Britain.

- 2

- 1

- 1

– Two, two… is this thing on?

I might have a little something on that front for you all tomorrow. Keep your eyes peeled…

Thanks Nathan! I can't believe this thing is now in its sixth year, personally. Can't spend too long thinking about that one…I am looking forward to seeing the end of this magnificent project. It has been a great ride, full of different ways of showing how your world has developed. The Redadder updates in particular were hilarious, and stood perfectly on their own if you knew nothing about the OTL influences (like me).

Glad you enjoyed Redadder! They were a blast to write.

Tell me about it. I spent the first two years this project writing about the years 1920–1966, then I spent the next three and a half years writing about the months May to December 1967. I had genuinely planned for all of this to be finished some time around January 2021. Never make plans, eh?I know what you mean. I have my current Presidents AAR sketched out to 1991, but I don't know if I will get that far either. After all, there is A LOT of things going on in the Sixties. In fact, I think I have spent more time on that decade than I did on the decades prior.

Thanks Kingmaker! Great to have you reading, even if it has taken me six months to express as much. Aberfan beggars belief. Simply an appalling tragedy, and I could not in good conscience leave it out here. It's proven quite pivotal, as I'm sure you've seen.I just read your update on the Aberfan disaster. My dad remembered hearing about it when he was a boy. Such an awful tragedy. It was nonetheless very interesting to read about it within the context of your alternate Britain.

__________________

It's half one in the morning here, so I'm going to have a sleep and then I'll do a typo check in the morning. For (almost) the last time: do not adjust your receivers!

- 3

- 1

- 1

Speaking of timing with regards to the pace: nothing less than majestic is proper for works that are seminal as the likes of @El Pip or, dare I offer, myself. I took nearly two years to advance the timeline perhaps a month...?

All that to say... We're ready for it, whenever it comes!

All that to say... We're ready for it, whenever it comes!

- 1

- 1

- 1

I think we must accept DB is currently winning this contest by a country mile. Even I must shiver in the shadow of such majesty as this;Speaking of timing with regards to the pace: nothing less than majestic is proper for works that are seminal as the likes of @El Pip or, dare I offer, myself. I took nearly two years to advance the timeline perhaps a month...?

That was December 2023. What can a mere mortal do against someone who considers 13months 'soon'? Indeed he hasn't actually posted yet, it could easily be longer. We are in the presence of greatness here.Hello everyone. A little update on scheduling.

See you all for more soon.

- 3

- 1

Speaking of timing with regards to the pace: nothing less than majestic is proper for works that are seminal as the likes of @El Pip or, dare I offer, myself. I took nearly two years to advance the timeline perhaps a month...?

All that to say... We're ready for it, whenever it comes!

Certainly, we three know an update appears never early or late, but always right at its appointed time.I think we must accept DB is currently winning this contest by a country mile. Even I must shiver in the shadow of such majesty as this;

That was December 2023. What can a mere mortal do against someone who considers 13months 'soon'? Indeed he hasn't actually posted yet, it could easily be longer. We are in the presence of greatness here.

That said, I was genuinely shocked to find that I’d managed to go the entire of 2024 without touching this. Another sobering reminder of the passage of time!

The chapter will very definitely be out today. Of course, when dealing with a world where seven months take 3.5 years to unfold, how long “today” encompasses is anyone’s guess…

- 2

- 1

- 1

In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority (Part Three: Red Autumn III)

Chapter Six

In Place of Strife: Lewis in the minority

Part Four

In The Autumn Of Our Youth: The Makings of ‘Red Autumn’ (III)

VI.

I have gone to great lengths so far, in writing this history of the political crisis that gripped the Commonwealth at the height of David Lewis’s term in power, to present it as primarily a crisis of the youth. I have written of a generation emerging into adulthood disillusioned by the choices offered to it, frustrated at the slow pace of reform and enamoured by extremist figures set upon achieving change by direct, sometimes violent action. It is true that much of the attention of the press during the most acute moments of crisis was pointed towards movements comprising and directed by young people. The eldest of Albert Roberts’s kidnappers was 30, while the youngest was some days off their 24th birthday. The Moss Side Five were all under the age of 27, and the student movement, being comprised overwhelmingly of undergraduates, was in large part made up of people barely old enough to vote. John Lennon, meanwhile, a hero to many of the disaffected, was still weeks away from his 27th birthday when his debut solo LP Institutionalised appeared in shops on October 20th. The record articulated well the volatile mood of the younger generation, who took to its trenchant, anxious, uncompromising material with eager enthusiasm. Discussions among the controllers of CBC Radio on whether, in the current climate, the music represented a dangerous intervention into public debate ultimately came down against banning it from being played on the air. But the fact that these discussions took place at all, among people who just three years before had been the ardent champions of a newly free media, demonstrate the extent to which Britain’s establishment classes had lost faith in the natural subservience of youth to experience.[32]

It would be a mistake, however, to neglect the extent to which the crisis of the late 1960s extended beyond the youth. Most obviously this was true in parliament, where opposition to the government’s programme was being led, in the form of Peggy Herbison and Jennie Lee, by two women in their sixties. The gadfly Assembly chair Michael Foot was in his mid-fifties – only a few months younger than the independently-minded TUC general secretary Jack Jones. One found their generational contemporaries well represented too among the leadership of the various opposition movements, both left (Bert Ramelson, 57; Ernest Millington, 51) and right (John Freeman, 52; Enoch Powell, 55). Prominent examples could also be found beyond Westminster – including, crucially, in the cases of the MAC and the Moss Side Five. Roberta Riordan, the primary school headteacher whose support encouraged the Five to continue their protest after the issuing of the injunction, was a direct contemporary of Herbison and Lee. And while not explicitly implicated in the activities of the MAC, Gwynfor Evans, the political leader of the Welsh autonomist movement, was the same age as Enoch Powell. Hence the picture that emerges is of a wide ‘cross-class’ alliance between the two cohorts at either end of what might broadly be described as adulthood.[33]

Protestors and rebels young and old contributed to a feverish atmosphere in the Commonwealth for much of 1967.

What united these two groups in their propensity for opposition? More pressingly, would their mutual mistrust of Mosleyism (and its alleged revenant in David Lewis) survive the present escalation? It is interesting in the case of each generation that it came of age, roughly speaking, at a time of left-wing political strength. Even the youngest members of the elder group were in their teens at the time of the revolution, while the younger cohort had grown up during the long years of Mosley’s downfall and the reforms of Aneurin Bevan. The oldest among each cohort, like Jennie Lee, or the revolutionary actress Vanessa Redgrave, now John Lennon’s partner, may have even been direct participants. Thus if one wished to theorise in crude psychological terms, one could say that each generation carried with it an optimistic faith in principle, or ideology, backed up, more pointedly, by a first-hand experience of successful direct action. In 1967, those now approaching their retirement had been the midwives of Britain’s ‘new tomorrow’, while their children had been the ones to wrestle some sense of that founding radicalism back from the clutches of Mosley’s long rule. Forty years on from the revolution that saw the end of the former United Kingdom, both were united in struggle against oppressive and authoritarian tendencies that threatened, as it seemed from their vantage point, to spell the end for the socialist Commonwealth.

Children enjoying May Day festivities in Tottenham, 1928.

Those still at school during the revolutionary years were approving the height of their careers in 1967.

If this lofty talk of principles and struggle threatens to overshadow a more sober engagement with the matter of what happened, and if postulations in the field of demography risk blotting out the verifiable historical record, as we head towards the final act of the Lewis premiership let us recall the facts. Upon coming to power in March, in the midst of the political uncertainty that followed Aneurin Bevan’s sudden death, Lewis inherited a stark list of issues in urgent need of addressing. Inflation was growing at its fastest rate since 1960, and economic contraction in two subsequent quarters over the long winter and uneasy spring of 1966-7 put Britain in a technical recession heading into the summer. Exacerbating the Commonwealth’s troubles massively was the unenviable fact that, over the previous twelve months from March 1967, the country had lost over 2.5 million working days to strike action. Iain Macleod, writing in the New Spectator had infamously diagnosed Britain’s ailment as ‘stagflation’; abroad, the ‘British disease’, a frequent topic of discussion in the international columns in Germany and elsewhere, was a complex illness whose symptoms included chronic low investment, both in new and legacy industries, a declining heavy-industrial base and resistance among economic planners to diversification in the new manufacturing industries opening up in Germany and the United States. The overall result, claimed critical economists both at home and abroad, was a loss of competitiveness in the face of a Mitteleuropean boom. As the years of the 1960s drew towards their end, it seemed as if the decade would be remembered as the moment when the non-capitalist world finally fell behind its free-market rival in all significant metrics of economic performance and general quality of life – perhaps for good.

Of course, nothing is permanent. The ultimate fragility of the central European Wirtschaftswunder, predicated as it was upon a stable and plentiful raft of American credit, was exposed barely a decade later when the various crises of supply and currency precipitated by the rash policies of President Nixon ravaged their way through the world’s dollar-backed economies in the early 1970s. With the benefit of hindsight, it is perhaps more than a little fortuitous that David Lewis’s full programme of market liberalisation, with its attendant integration of Britain and the Eurosyn bloc into a wider network of cooperation with the ECZ and the dollar zone, was not seen through to a more complete stage of realisation. Certainly, when only five years later the Eurosyn, buoyed by the accession of Portugal into the bloc as the fifth fraternal commonwealth, briefly retook the economic advantage over its eastern rival, beleaguered by the first jolts of the energy crisis, the Commonwealth seemed vindicated in its decision to reject Lewis’s iconoclasm in favour of steady-as-she-goes orthodoxy. But if in 1967 Chairman Lewis still appeared to be an old man in a hurry in his haste to overhaul a tired economy, we must remember that none of what was to come could have been confidently predicted, far less guaranteed. By October 1967, although undoubtedly rocked by the social unrest of the summer and early autumn, David Lewis had reason to believe that his project was working. Economically, Britain had won a reprieve from its brief dip into recession thanks to growth, barely appreciable but real nonetheless, of about 1 per-cent in the summer quarter. While students filled the streets, it was easy to forget that the Commonwealth’s working base was not in an overly combative mood for much of 1967, and the massive drop in days lost to strike action compared to the year before (abetted somewhat by warm summer weather insulating the country from shocks to the coal supply) did much to steady the ship. Similarly, while Lewis’s flagship programme of managerialisation had been met with widespread controversy, and hampered by resistance in the most radical industrialised areas of South Wales, South Yorkshire and the North East, industrial secretary Jim Callaghan’s adroit intervention had rescued the policy, conceding that managerial responsibilities could rest with shop stewards rather than external appointees. That one more moderately minded member of the TUC’s national executive could describe the implementation of ‘shop-steward management’ across the country in the autumn of 1967 as ‘a great victory for the workers’ was by no means insignificant. Lewis’s relations with all but the most militant of the Commonwealth’s trade unions had turned a corner after their rocky beginning, and while conflict still loomed over the matter of the Industrial Relations Bill and its much denounced ’28-day clause’, recent history suggested that this need not be fatal to either side.

German manufacturing, 1950s.

Bringing the Commonwealth’s economy up to speed with its competitors in the German-led central European bloc was at the heart of David Lewis’s economic plan.

What, then, if not a basic failure of economics, finally scuppered the Lewis project? Consensus over the last decade has tended to settle on his personal qualities, his impatience and frequent unwillingness to compromise, taking these elements of his personality as proof that any government he led was always bound to come undone before long. No doubt, these qualities did little to help Lewis at key moments of his premiership, though neither had done him serious harm over the course of his thirteen-year leadership of the Popular Front, when he had proven himself time and again not unaware of how to balance toughness with tact. To focus too heavily on psychological factors in isolation, then, would be to ignore the factors – and, perhaps more pressingly, the people – beyond Lewis’s control, whose own hard-headedness and drive contributed to the government’s downfall.

Such was the force of Lewis’s personality as premier that it is easy to forget long after the fact that his government was a coalition, and a frequently uneasy one at that. At the election in May, the Popular Front and the Labour Unionists had each secured roughly a third of the vote, and in many ways it was a fluke of circumstance that it was Lewis and not Dick Crossman who ended up in the commanding position. So secure seemed the alliance between the two parties, entering its third decade, that it was easy to forget its obscure origins as a marriage of convenience. In the mid-thirties when Oswald Mosley turned to Stafford Cripps and his party for support in shoring up his position against the bruised, warring remnants of the Communist bloc, he could scarcely have grasped the full consequences of the arrangement into which he was entering. For two decades afterwards the alliance between Mosley’s party and the Popular Front represented the broad consensus of the mid-century that favoured a centralist, corporatist government whose taste for welfarism nevertheless rejected outright socialism. When, in time, Lewis and Bevan replaced first Cripps and then Mosley, the specifics of the pact altered without too greatly upsetting the fundamentals. Lewis chafed under the mantle of corporatism, ever more vocally after 1959, while Bevan was more of a socialist than Mosley ever had been even in the latter’s most cynical pronouncements. In the brief years of reconstruction after Mosley’s ousting, the alliance remained intact on the strength first of the necessity of the task at hand, and secondly on the basis of the personal warmth between its two leaders. But the divergence had been set in motion, and with Crossman leading the Labour Unionists after Bevan’s death there was precious little personal warmth to plaster over the widening gap. Far from representing a broad but unified coalition of the centre ground as in 1935, by 1967 Crossman’s party, keen to shed its poisonous Mosleyite inheritance, had taken decisive steps towards socialism while Lewis was left the lonely standard bearer clinging to the centralist flag.

Dick Crossman.

Slowly drifting apart as it became clear that they held divergent answers to the question of what to do with the economy after Mosley, it was in the social sphere that the extent of the two parties’ differences was most starkly exposed. This owed as much to history as it did to political pragmatism on the part of Crossman and his colleagues. The Popular Front remained, as they always had been, the natural party of the older, independently-minded educated and professional classes, who a decade earlier had often disdained Mosleyism only marginally more than they had disdained its most vocal left-wing opponents. In the 1960s, the Popular Front still uneasy though uncomplaining beneficiaries of the revolution-era interdiction on pro-capitalist political parties, this demographic could still be counted upon at the ballot box, the competing option of the Social Democrats not yet a viable (or available) one. For the Labour Unionists, on the other hand, divorce from Mosleyism and the full conversion to welfarist socialism had left them vulnerable to competition from the young parties of the New Left, who offered socialism unsullied by Mosleyite history or awkward tussles with the trade union establishment. Knowing that he could not take votes from Lewis’s constituency, Crossman can not be faulted for planting his flag in redder territory. Moderate support for the new issue of autonomism would keep the party from ruin in its South Wales heartlands and other places – an acute possibility after the horror of Aberfan – while principled opposition to the erosion of the rights of unions would keep the old unionist bloc satisfied. If Crossman may be faulted, it should be for the fact that with three full years left until the next scheduled elections he was dancing this dance in such teasing view of the public eye. But he can hardly be faulted for dancing it at all.

The eventual collapse, then, of the Lewis government must surely be characterised in the final view as the unfortunate product of a political divorce arguably long overdue. Were it not for the spectacular backdrop against which it took place, lit up by telegenic kidnappers and spirited radicals of all persuasions, it would perhaps be much less passionately remembered. Nevertheless, as both the premature culmination of a fiery decade of change and the tumultuous prelude to another, more significant period of realignment in British society, whose aftershocks we still experience at the time of writing, it rightly remains a period ripe for historical enquiry and re-evaluation. As we move into its final act, I caution only that we must not lose sight of the tangible record in the face of the heady seductions of myth, drama and legend.

*

VII.

Insofar as David Lewis was a radical, he was a radical of the ballot and not of the bullet. The premier’s activities as a youthful firebrand had barely extended beyond the chambers of the Oxford Union[34], and having neatly avoided the worst excesses of revolutionary violence in Britain by virtue of having been in Canada, there can have been no sense of betrayal of an old Romantic revolutionary self in his unsentimental attitude towards the two MAC kidnappers killed in the failed mission to rescue Albert Roberts. The matter-of-factness of this reaction must not mask the gravity of the event. Stern resistance from the authorities, sometimes armed and frequently violent, had greeted the numerous protests that had marked the final years of Mosley’s rule, still barely a decade in the past in 1967. Still, even at its most boisterous the latest wave of protest had remained basically peaceful, pushing and shoving of crowds or the occasional improvised missile thrown by protestors against shielded WB volunteers about as close as things had come to violence. The killing of striking miner Gwion Parry when he was struck by a lorry attempting to break the occupation of Deep Duffryn colliery in January had been met with universal denunciation from the political establishment. Parry’s death was an unthinkable tragedy and the shock that it had sent through the country contributed directly to the concession by the Bevan government, in one of its final acts before Bevan’s death, to the agreement of a settlement over the fate of the Free Pits in February. The driver who killed Parry had only recently been convicted of his manslaughter when David Lewis’s announcement of the attempted rescue of Albert Roberts hit the headlines. The reaction which greeted the news, while no less vociferous, was tainted arguably with even greater controversy.

David Lewis’s statement, repeated first in the evening newspapers on Thursday 11 October, that ‘in the course of [the attempted rescue] operation, Mr Roberts was killed’ was striking first of all for its stark message, and secondly for its lack of detail. That this was carefully calculated is so obvious as to hardly merit saying. Similarly, the subsequent revelation that ‘in addition to the death of Mr Roberts, two of the MAC paramilitaries were also killed during the operation’ was a fine piece of passive-voiced obscurantism. The question, surely, was: what is it that is being obscured? If nature abhors a vacuum, seldom is this more sharply illustrated than in the case of commentators making gossip of innuendo. The government’s official line, that the security services could not release further details so as not to prejudice an ongoing criminal investigation, may have rested on a valid premise, but it did little to quell the immediate suspicion – alive not only in opposition circles – that lurking in what had not been said were hints of foul play. What details did emerge in the coming days did little to extinguish the sparks of controversy. In its Friday morning edition, national paper of record the Daily Herald led with a restrained headline, ‘Roberts, Two Kidnappers Killed in Rescue Attempt’. The Herald cited anonymous sources in the Domestic Bureau who alleged that the former coal boss had been killed in a firefight between BDI agents and the kidnappers during the attempted rescue, though they offered no further clarification as to whether Roberts had been killed by his kidnappers or the BDI. Domestic Secretary Dick Crossman also refused to be drawn, and was quoted only as offering his condolences to Roberts’ family and expressing a hope that what he called ‘this tragic incident’ would serve to stem the rising tide of extremism in Britain.

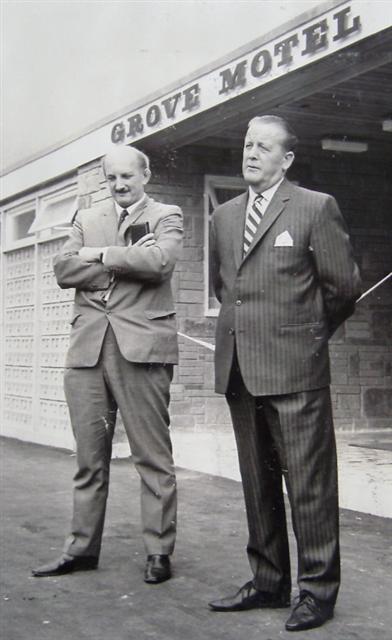

Albert Roberts (right).

Crossman sidestepped the issue of offering condolences to the families of the killed kidnappers, now named as Llew Vaughan and Daffydd Evans. His only comment regarding the three arrested MAC members – Gwyn Iorath, Siân Griffiths and Eluned Wyn Parry – was that they had been remanded in custody and would be brought to trial as soon as possible. The three comprised an unlikely group of would-be paramilitaries. Iorath, the eldest though still only 28, was a PhD candidate in the Welsh-language department at the University of Wales in Bangor. Wyn Parry, 26, was a trainee teacher and also Iorath’s partner, while Griffiths, only 24, was Wyn Parry’s cousin. Of the three, it was Griffiths who had had the most verifiably radical political career to date, having spent a week in prison four years earlier for non-payment of a fine earned for defacing an English-language road sign as an activist for the Welsh-language campaign group Cymdeithas yr Iaith[35]. Iorath and Wyn Parry had also been members of Cymdeithas, but the explicitly non-violent organisation seemed an unlikely nursery for future terrorists.[36]

Clearly, at some point the trio had been radicalised beyond student vandalism. The answer to this question seemed to lie, tantalisingly, with Vaughan and Evans, the two kidnappers killed in the storming of the Anglesey farmhouse in which the quintet had held Roberts captive. Both older than the surviving trio, the pair had apparently been known to the authorities for some time before the kidnapping as associates of an earlier group suspected of carrying out minor bomb attacks in the early 1960s. Their intent earlier in the decade had been to sabotage the construction of a reservoir in rural north Wales, whose water would supply towns across the border in Merseyside and came at the cost of a Welsh-speaking village, which was flooded.[37] Vaughan and Evans had grown up around Bangor, where Iorath was studying and lived with Wyn Parry, but details of how the five came to be associated with each other have yet to make their way into the public record. We will perhaps not know the truth of the matter until the start of the next millennium, when the government files relating to the case are marked for declassification. Certainly, however, in 1967 the vast majority of talk that surrounded the arrest and subsequent trial was hearsay. When the government finalised the charges to be brought against the three later that autumn, they included a number of charges relating to the bombing of the coal exchange in Cardiff and the attempted bombing of a British Coal lorry depot at the end of summer. At their initial hearing in November, Iorath, Wyn Parry and Griffiths pled guilty to kidnap but pled not guilty to the bombing charges, maintaining that these had been the work of Vaughan and Evans alone. If the not guilty pleas to the bombing charges did little to calm the growing sense of controversy attaching itself to the trial, far more incendiary was the government’s final sally. Presenting their initial case, the authorities moved at last to seal shut any room for speculation surrounding the circumstances of Albert Roberts’ death during his ill-fated rescue. The government line was made clear by its prosecutors at the November hearing: Roberts had been killed by his kidnappers, they alleged, when the failure of their enterprise had become obvious. Not knowing which of the group had been the one to carry out the deed, the three detained suspects were all to stand trial for his murder by the doctrine of joint enterprise. All three vigorously denied the charge. With the full trial set to begin in the middle of January, there would be no closure to end the year. Lewis’s government seemed only to be gaining momentum, in fact, in its ability to attract scandal.

Protest in support of the Moss Side 5, uniting teacher colleagues and students, October 1967.

If Lewis had been able to face down critics of his stern response to the Welsh kidnappers on the grounds that their alleged crimes were so serious as to demand a strong reply, he had a harder time shaking off the more general charge that his government was becoming increasingly quick to turn to strongman tactics in attempting to solve its problems. In the same week that the MAC members had been formally charged, in Manchester the five teachers at Moss Side primary school who had defied a court injunction to continue their unofficial strike over far-right intimidation the previous month, stood trial at the magistrate’s court. The specifics of the Moss Side proceedings were far less eye-catching than those relating to the Roberts case, hingeing as they did on technical charges of contempt and violations of somewhat arcane industrial law. The coincidence of the two events galvanised proceedings, however, and the five teachers found themselves subject to no shortage of attention – and with it frequently sympathy – from the press. The image of the primary school teachers in court for having protested fascist intimidation, whatever the legal merits of the case against them, struck a chord with many in the country who suspected that something had gone slightly wrong with British society to make radicals of bookish professionals. So too the lingering suspicions around the three MAC defendants, also teachers and university students, to whom allegations of kidnap – never mind murder – never seemed to stick entirely convincingly. Joan Lestor, then the education spokesperson for the New Left Coalition, made a similar point in the Assembly at the end of November once the so-called Moss Side 5 had been found guilty, their arguments of innocence on grounds of a fundamental right to protest doing little to impress the presiding magistrate. ‘Where have we arrived at as a society,’ Lestor began, ‘that five young women who have so far dedicated their lives to one of the most kind, noble causes imaginable, the care and education of our children, are today in prison, where they will likely spend Christmas, for having done nothing more grave than take a peaceful stand against the rising tide of right-wing bigotry and hatred?’[38] She continued:

It should be our great collective shame to report that this bigotry is once again resurgent in Britain, yet we are silent. Are we really so precious as a society in our need for order that we cannot stomach being told, exceedingly politely I might add, that we here in Westminster might, on occasion, be wrong? Kidnap, I grant, is the sort of extremism that we should make clear is not welcome in our democracy. But we must ask, in our response to it, whether we ourselves are not also partially culpable? I challenge the comrade members here today to reflect; if it is democracy we claim to be upholding and protecting, what sort of democracy can we boast of when it takes a kidnapping for the frustrations of a community of nearly three million people even to be discussed seriously in this Assembly?[39] And more than that, how healthy can we really call our democracy when its laws are seemingly enforced with such haphazard application? It has barely been six weeks since right-wing demonstrators flew an old flag of the British Fascisti on the streets of Birmingham, an act that I need not remind the comrade members is not legal under our present constitution, and yet there has been no response from the government. Are we to draw the conclusion that this government acts only when it suits its own purposes? The comrade premier’s recent difficulties in bringing the unions to heel have been well documented, and his attempts to force the matter of unofficial strikes in the courts during the Manchester demonstrations last month are also a matter of public record. Can the government reassure us that it is not playing politics with our democratic institutions, or will we be left to infer as much from a continued campaign of ‘discipline at all costs’?

Joan Lestor, posing for photographers while campaigning in April 1967.

Lestor’s comments hit the government benches keenly. Lewis’s responding protest that her accusations of ‘playing politics’ with the constitution amounted to language unbecoming was upheld, one imagines with some regret, by Assembly chair Michael Foot, requiring a partial retraction. But it was a hollow, technical victory, and Lestor’s point had been made with some force. She can not have been the only one to speculate whether Lewis’s outward toughness was calculated to mask an increasing inability to deal with his unruly government coalition. Lestor’s reference to ‘the comrade premier’s recent difficulties’ was particularly cutting in this regard, coming only a week after Lewis had been forced to make an embarrassing climb-down over the Industrial Relations Bill and its contentious 28-day clause. Dick Crossman, knowing that opposition within the ranks of his own party to the clause was growing, coordinated by the veteran rebel backbenchers Jennie Lee and Peggy Herbison, had urged his coalition partner to amend the legislation ahead of its third reading after recognising signs of the strength of the probable dissent at the Labour Unionist annual conference in October. A motion from the floor, sponsored by a group of Welsh delegates, requiring the parliamentary party to withdraw from its coalition with the Popular Front in protest of both the latter’s growing authoritarianism and Lewis’s continuing campaign against the Welsh coal industry, had been defeated by a much narrower margin than anticipated on the conference’s final day.

Crossman (right) and Callaghan in 1967.

(Anyone interested in the pair's relationship in our own timeline might enjoy this colourful reporting by the New York Times in 1977 on the occasion of the publication of the final volume of Crossman's diaries. Roy Jenkins, our putative author here, also shares his views on Callaghan's reputation.)

Elsewhere, in a repeat of talks that took place ahead of the bill’s introduction to parliament in May, Jack Jones and other representatives of the TUC had met with Crossman and Jim Callaghan a final time in an attempt to moderate the offending clause in the lead up to the November vote. Jones, who was in favour of a setting up a new conciliation body in principle, was prepared to forego his personal preference that any such body be empowered only to arbitrate on disputes already in progress, lobbying for a revised amendment which merely reduced the ‘cooling off period’ to a week or fourteen days. Callaghan, more than amenable, regretted that Lewis was adamant and his hands were tied, and the eleventh-hour intervention came to nothing. Privately, both Callaghan and Crossman attempted to alert Lewis to the potential for rebellion, Crossman in particular cautioning the premier in no uncertain terms that even with a three-line whip he could not be sure of total obedience from his party. But Lewis was resolute; this was the government’s programme, as agreed in May, and if Crossman was serious about his party remaining in government he should deliver the votes or consider his position.

If this was a stern warning to his coalition partner, Crossman’s commitment to the shared project was also, by this stage, an increasingly big ‘if’. Under no illusions about the likelihood of a rebellion, Crossman met with Lee and Herbison on November 6, the night before the vote, to ascertain what size of protest he might expect the following day. Lee and Herbison advised that they had just over 60 members confirmed as voting against the bill – a third of the parliamentary party – but that perhaps 60 more were still ‘examining their consciences’. This uncertainty did little to help the situation; the government’s majority stood at 163, meaning that 82 defectors could swing a vote and bring down the bill.[40] The outcomes suggested by Lee and Herbison’s prediction therefore ranged from profound embarrassment for the government to its outright defeat. In either case, Crossman had a serious headache ahead of him. When the following morning 87 Labour Unionist members voted against their government it was enough to scupper the bill’s passage by the slimmest of margins, leaving Crossman to deal both with an outraged Lewis and a parliamentary party increasingly immune to threats of discipline in the name of unity.

Crossman.

Lewis was the first to reach the beleaguered Labour Unionist leader, demanding an explanation for the humiliation and reminding his colleague that he would have to sack the 26 government ministers who had voted against the bill – a fact Crossman was of course well aware of. The scale of the crisis which now presented Lewis could hardly be overstated. To be sure, those of the country’s political correspondents present that day in Westminster were already queuing for the lobby telephones, ready to relay back to their editors auguries of doom for the coalition government. More than a simple rebellion, it appeared that the fundamental understanding of the common cause which had united the Popular Front and the Labour Unionists in their alliance for over a generation had been eviscerated in this mass display of dissent. The underlying assumptions that had undergirded British politics for decades, that the coalition parties represented two temperaments of the same fundamental character, whose differences in working towards a strong, welfarist state were mostly aesthetic, had been exposed as superannuated in the most public of forums. As Lewis scrambled to fill the new vacancies in his government and reflect on where next for his plans for bold reform to the laws governing industrial relations, Crossman too had his own unenviable task: to face the decision which he and his parliamentary party had been putting off confronting for some time.

Jennie Lee speaks in the Assembly against the Industrial Relations Bill.

When Crossman eventually convened an extraordinary meeting of his parliamentary party in the Cook Rooms above the main chamber of the People’s Assembly on the evening of November 8, the atmosphere was not entirely comradely. Of the 180 Assembly members elected in the Labour Unionist interest at the start of May, 87 had rebelled against the government to scupper one of its key policy proposals – albeit one that had already been subject to vociferous internal opposition. In normal circumstances, rebellion in a vote of this importance would compel that one be relieved of one’s party affiliation. Clearly, the scale of the ranks of the rebels meant that this was not an option for Dick Crossman, who could not afford to suspend almost one half of his parliamentary party. Instead, the situation would demand a frank accounting process and some sort of rapprochement between the loyalists and the dissenters, both to determine what exactly had led to the fissure and how it might be swiftly repaired. Charges levelled against Crossman that evening mostly coalesced around a perceived unwillingness to push the Labour Unionist agenda in government. The party controlled, after all, nearly one half of the government’s seats. In percentage terms, the difference between the two coalition partners was a statistical irrelevance. How, then, barely six months into the government’s lifespan, had David Lewis got to the stage of being able to order half of his colleagues about as if they were hardly independent at all? Surely it could not entirely fall down to the dominance of one strong personality. Crossman, a veteran survivor to rival Lewis himself, was no slouching pushover. What was it about his conduct that had given Lewis the idea that his support, and the support of his party, could be so easily taken for granted?

Of course, the fault was not entirely Crossman’s, and any discounting of Lewis’s own bruising nature risked overcorrecting in reaction to the shock of the bill’s failure. But while to call Crossman weak in the face of his coalition partner’s leadership would have been unfair, it was true to say that the styles of the two men, and the manifestations of their respective strengths, differed appreciably. Lewis and Nye Bevan had been well matched in many ways – two prize fighters of the old school forged in conditions of great, urgent difficulty, and adept after their long careers at mastering unrest. If Bevan’s political style had been an exemplar demonstration of what the Welsh call hwyl, Lewis surely had received an equally strong inheritance of what his Yiddish-speaking forebears might have called chutzpah.[41] The two unquantifiable, slightly mystic forces were well balanced, and over long careers working towards shared goals Lewis and Bevan had developed a deep mutual respect for each other’s strengths. Bevan, of course, had flagged first, sapped and then defeated by illness. Lewis persisted, but his unsubtle management of the present coalition suggested one of the ways in which British politics had changed rapidly without him yet having noticed. The donnish Crossman was as good a representative of the emergent style as any. The man whom watchers of Westminster business had called ‘Tricky Dicky’ long before any Americans presidents were to popularise the epithet was a keen adept of the backrooms, negotiating his unassuming way towards power in the shadow of those more stridently up for a dogfight. In the long Mosley years, this had kept Crossman in the second tier of Westminster operatives, lacking the outward willingness to get his hands dirty. But the new consensus valued the skills of discussion and mediation in which Crossman was so well practiced, and the Commonwealth in 1967 was quickly declaring itself to be done, in its parliamentary politics at least, with out and out fighters.

President Ian Mikado addresses his colleagues in the Cook Rooms.

In the Cook Rooms, Crossman took on the frustrations of his colleagues with good grace and waited to give his appraisal of the situation. When it came, it was characteristic. The party, as he saw it, had two options: either they could come to a common cause, in one direction or the other, and face the consequences together, or else they could split and face certain ruin. Put in such stark terms, the assembled membership showed that they were not, fundamentally, self-destructive. Peggy Herbison, the widely respected rebel leader, took up Crossman’s cue. ‘It is clear,’ she said, ‘that we are not, as a cohort, satisfied by our position in the present government. Let us therefore settle the matter plainly: shall we stay in coalition, and accept all that that entails us to accept, or shall we put our money where our mouths are and go?’ Herbison’s intervention caused uproar, but when order had been restored sufficiently for a show of hands to be taken, it was clear that she had captured the mood well. By a margin of 122-58, the Labour Unionists indicated that they would prefer to leave the governing coalition. It now fell to Crossman to see whether he could salvage any sort of compromise with Lewis, or whether the Commonwealth’s continuing political deadlock was about to enter a brand new stage of severity.

*

VIII.

We must be thankful to Dick Crossman that he was such a colourful and assiduous diarist. Recounting his first meeting with David Lewis after the Cook Rooms debacle, he notes that Lewis arrived five minutes late and declined to waste time with pleasantries. Crossman regarded this unsubtle attempt at dominance with wry amusement, writing, from his point of view as an old don, ‘it was as if we were back in Oxford, and he was trying to freeze me out like a recalcitrant first-year’. But Lewis knew full well what it was that kept Crossman from taking this display more seriously: the premier still needed his colleague’s cooperation if the government he led were to survive the winter.

In deference, perhaps, to old collegiate feeling, Lewis refrained from relitigating the travesty of the defeat of the Industrial Relations Bill and let Crossman move on to the present predicament. The Labour Unionist leader told his Popular Front counterpart the plain facts: his parliamentary party had indicated in a vote by more than a two-thirds majority that, given its present course and character, they would prefer to leave the coalition. The summer crisis had stretched party opinion to the extent that it no longer could support the present, authoritarian programme. In truth, the first hint of these cracks may have been sensed as far back as February when, nine long months before, Anuerin Bevan, in a final, magnanimous gesture, had conceded the possibility of worker self-management to break the deadlock in the coal industry that had persisted from the previous autumn. Bevan’s February settlement with the miners’ union had opened the floodgates on a debate which, until then, had been held in check for a generation, that Britain’s working classes had a right to take part in the direction of their own labour. It hardly seems so significant for a state which still, in spite of thirty years of recent history, clothed its discourse in socialist garb, but as we have seen it is not so much the dress as the behaviour that is crucial. Bevan’s death a few short weeks after this concession seemed to cauterise, temporarily, a wound that needed fresh air to heal. The subsequent formation of the latest coalition between the Commonwealth’s two main parties, this time underscored by solemn references to unity after the shocking demise of the late premier, seemed to sweep aside any prospect of continuing the debate in favour of a return to politics of common purpose. But the common purpose had been assumed more than it had been articulated, and now its inadequacy was thrown into full view.

The consequences of Chairman Bevan’s eleventh-hour move towards autonomism continued to be felt in government eight months after his death.

After the May election, David Lewis had attempted to bluff his hand, parlaying his modest plurality at the polls into a strong mandate for his vision of change. Capitalising on indecision in the Labour Unionist ranks, who still reeling from the death of their charismatic figurehead had not yet come to terms with the full implications of his final act in power, Lewis had been able to press his centralising ambitions onto the coalition as a whole over any forming dissent. But the ruse had now run out of steam, and the premier knew it. Salvaging the coalition would now require, in effect, a complete rewriting of the terms of alliance. Crossman proposed as much: a weekend of emergency cross-party talks between grandees from the Popular Front and the Labour Unionists, in a final attempt to repair the coalition’s working relationship. Lewis was well aware that, on this occasion, he had been played into a corner, and after lunch on Friday talks began.

Meeting at Chartwell, the magnificent home reserved for use by the Commonwealth’s premier, which in pre-revolutionary times had been the country seat of the United Kingdom’s disgraced final prime minister Winston Churchill, a committee of eight met to determine the fate of the government. In attendance from the Popular Front were David and Barbara Lewis, their close if pragmatic ally Jim Callaghan, and Michael Foot, hardly an ally of the Lewises but invited, one imagines, both for his practical influence as Assembly chair and his close friendships with many in the Labour Unionist ranks. The four Labour Unionists were Crossman, Peggy Herbison, Jennie Lee and Ian Mikardo, the president of the Commonwealth. The specific points up for discussion primarily involved how to move forward with reform to trade union law following the defeat of the Industrial Relations Bill, though talks also looked ahead to the Mines and Quarries Bill whose likely contentious third reading was due in month’s time. From the start, discussions were fraught; often in the months since the election, Labour Unionist ministers had complained that their premier had little time for them, preferring to keep the counsel of a close circle of party colleagues, and the long weekend at Chartwell promised to provide out-of-favour Labour Unionists Herbison and Lee with unprecedented access to the government leader. They seized their moment keenly. Crossman records in his diary, no doubt exaggerating somewhat, that Lee and Lewis almost came to blows over dinner on Friday night when Lewis reacted dismissively to a suggestion by Lee that he could learn from her late husband’s willingness to change course after the disaster at Aberfan, apparently taking the suggestion as ‘sentimental nonsense’. Lewis meanwhile lamented the willingness of his Labour Unionist colleagues, Herbison and Lee in particular, to ‘martyr themselves’ for principle when they could be helping with meaningful work in government, not simply ‘wrecking’ from the outside. Clearly, it was an opportune moment for all involved to get plenty off their chests.

Chartwell, Kent, as seen from its rear garden.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to suggest that the Chartwell talks were entered into by any of the participants in bad faith. All involved were sufficiently well practiced in politics to take seriously the gravity of the discussion, and Saturday proved more fruitful. Perhaps re-energised by the morning views over the Weald of Kent – so stunning as to have compelled Churchill to buy the house 45 years earlier – the eight were in sufficiently good humour to agree a compromise on the Mines and Quarries Bill, scrapping the thorny ‘closures clause’ that promised to grant the government sweeping powers to shutter mines on the basis of poor safety standards, and instead empowering an independent commission to review Britain’s coal reserves and make recommendations for closure accordingly. Much-needed investment in safety would be preserved as a separate matter.

The fundamental question, however, remained to be totally fixed. In spite of the progress made on specific issues, by Sunday it still seemed uncertain that there was hope for the coalition as a whole. Lewis’s pragmatic willingness to look again at one thrust in his sally against the strength of the coal industry did little to repair the broken sense of trust between the two parties, or alter radically how its members would look at each other second guessing motives sat side by side in Assembly committee rooms. There was also the reality to face that those leading the repair efforts were fatigued, personally, both by the stress of recent years and before that by long careers in difficult circumstances. If the ghost of Aneurin Bevan hung heavy over proceedings, it seemed fitting in part that the mood should be set by memories of the man who more than any of his peers had committed himself so fully to the defeat of Mosleyism. Though Bevan had discovered within himself after 1961 an almost miraculous second wind in order that he might put down Mosley’s would-be successors, he could not rally a second to correct the mounting crises of his latter years.[42] Increasingly, there was a sense of Britain’s political leadership doing battle with ghosts, seeing issues not as things to be met on their own terms, but as harbingers of greater existential questions concerning the fate of our young democracy in the first decade after Mosley. To be sure, we must not dismiss too quickly the anxieties of a generation whose mature careers took place almost entirely in times where authoritarian attitudes were king. As I write, both the Catlin government’s Freedom of Information Act and the final report of the Commission for Truth and Reconciliation, two landmark interventions in the long process of ‘Demosleyfication’, remain things of the recent past; we too face our own battles with the beast. But this climate weighed far more heavily upon the protagonists at Chartwell than it does upon us today, and we must not judge them too harshly if having steered us safely through the storm they lacked the energy for a long journey through uncertain waters.

David Lewis.

By the end of 1967, his powers were beginning to fail him.

It fell at last to Dick Crossman to capture, poignantly, the mood that prevailed at the end of the weekend:

It was David’s silence, above all, which stuck with me as I got into the car for the drive back to Westminster. Here was the great fighter, the most improbable of our premiers, who had stood up to Mosley at the height of his powers and survived; the towering innovator of parliamentary Marxism whom Michael [Foot] still credits, his disbelief more palpable with every retelling, with bringing him over to socialism at Oxford[43]; the only one of us, in the cold light of day, whose integrity can have been said to have survived the dark years fully unscathed, so clear-sighted was his understanding of the old regime that he was prepared to reject it even when Nye still played hokey-cokey with his allegiances. The hero who only now had stepped belatedly and defiantly into the spotlight found that all of his lines, all of his set pieces, all of his tricks of expression and gesture had deserted him, and he was left to face alone under the white glare of the bulbs an audience whose patience was spent. On Friday evening he had mauled and harangued us, provoking us into action and geeing us up for a fresh fight. Forty-eight hours later he had seen the tide turn; he recognised that the great heroic age of our politics had ended, that each of us, privately, had made peace with our new, diminished position in the world, bewildered, tired and yes bereft, but thankful equally to have come through it all intact. How lucky we were to have been there on the front lines and still lived to see the armistice. But it is the curse of all lucky generals that they must go home to die in their beds. At the flat I telephoned Edward [Short, the Labour Unionist chief whip], who was not very happy to have been woken up, and asked him to assemble p[arliamentary] p[arty] first thing so I could tell them the news before I told the Assembly.

The news that Crossman had to impart so urgently was of course the finalisation of the divorce between the Labour Unionists and the Popular Front. At midday on Monday 13 November, Crossman spoke for the first time from the opposition benches to inform the Assembly that the Labour Unionist Party had left the governing coalition. Instead, the party would continue support the government bill by bill on a confidence and supply basis, though given the rift that had developed between them and the Popular Front it remained to be seen how effectively this arrangement would work in practice. Crossman paid warm tribute to his former colleague, praising Lewis’s ‘admirable strength of character in the face of numerous challenges’. Still, he regretted that ‘irreconcilable differences of opinion’ over recent legislation and other issues had forced the Labour Unionists to consider their position in government. Lewis, Crossman assured the Assembly, still retained his full confidence as the right man to lead the British government, but he could no longer serve as his deputy.

Crossman announces the news of the coalition's split.

Lewis responded gracefully to Crossman’s statement, thanking his former deputy for his work during their time in coalition, and he assured the house that his government would continue to the best of its ability to carry out the programme on which it had been elected in May. Ernest Millington, the principal spokesman for the New Left, protested that the minority government with which the Commonwealth now found itself represented a failure to the voters, but his attempts to rally a vote of no confidence in the new ministry came to nothing without Labour Unionist support. Ignoring the protests, Lewis set his mind to his next task, to see through the passage of the defanged Mines and Quarries Bill in a month’s time and keep his government alive into the Christmas recess, and with it the new year.

Millington, clearly, was right. The new ministry was a farce, and Lewis himself knew this only too well. Shorn of nearly half of its members, the government’s ability to pass any new legislation would be wholly dependent upon Crossman’s party, severely limiting the scope and speed of what it might accomplish. Arguably, all that this required in practice was what the business of coalition had already implied, that the parties achieve consensus on a shared programme before presenting legislation to the Assembly as a fait accompli. But if Lewis had still held the appetite for this way of working, he would not have been in his frustrated position at all.

Janet Unwin, the most prominent of the 'Moss Side 5', collects flowers from family, friends and supporters as she leaves prison in December 1967.

It can have been no secret that dissolution was on Lewis’s mind, even if he was not yet saying so publicly. Odds on an election in January or February shortened considerably with the government’s loss of majority. January, perhaps, would have always been premature; able to avoid controversy at least until the Mines and Quarries Bill passed its final reading on December 18, only three days after the five imprisoned teachers from Moss Side were released on parole, the government had achieved its aim of surviving until the winter break and could at least claim to have reached Christmas with an air of some good feeling. It was to prove a final moment of optimism. According to a poll in the Daily Herald published on New Year’s day, Lewis’s government began 1968 with an historically low approval rating of just 22 per-cent. When the Assembly reconvened on January 8, Ernest Millington dutifully attempted another motion of no confidence. Again, the Labour Unionists refused to join him and the enterprise came to nought, but with every day the government survived in its paralysed state it became harder to defend its continued existence.

Siân Griffiths (left) and Eluned Wyn Parry pictured being led into court during their trial alongside Gwyn Iorath for the kidnap and murder of Albert Roberts.

The young, somewhat unlikely paramilitaries captured the imagination of a wide section of the youth counterculture, and support for the three during their trial remained consistent outside of Wales as well as within it.

The beginning of the MAC trial on January 15 briefly shifted attention away from the government’s woes, though soon worked only to refocus criticism of Lewis’s authoritarian streak. Owing to the fact that the details of the case hinged on what the government deemed sensitive matters of internal security, the new domestic secretary Bob Mellish had restricted media access to the trial, culminating in the farcical routine of journalists being required to vacate the courtroom whenever active members of the security service were giving testimony, as happened frequently. In the absence of consistent dispatches from court, the press were left to garnish the redacted transcripts to which they were given access with as much conjecture and innuendo as contempt laws would allow. The images of the young, bookish kidnappers lead into court each day, handcuffed and under heavy guard as their alleged status as terrorists demanded, only heightened the drama of the affair, the display coming perversely to portray much the opposite of what was intended, that this was a government, in spite of everything, committed to the thorough and sober administration of justice. After three weeks, on Monday 5 February the three kidnappers were found guilty on all charges and each sentenced 25 years imprisonment. Two days later, perhaps hoping to take advantage of a reviving sense of strength, perhaps seeking to bury news which had already led to public demonstrations throughout Wales and at several English universities, David Lewis addressed the Assembly to announce, at last, what had been expected for some time. Parliament was to be dissolved the next week, with the election set for March 14. Sensing the end for a figure who had given his life to British politics at the highest level across three long decades, the correspondent in the sympathetic Tribune reported on the occasion in the manner of an obituary. He reached, however prematurely, for the Bard, and one can hardly fault his choice as inappropriate:

He was a man, take him for all in all,

I shall not look upon his like again.

___________________________________

32: Even youthful CBC 2 controller David Attenborough, who had a strong claim to have done more than any other person in Britain to facilitate the acceptance of the first generation of beat groups by the wide television-watching public, expressed doubts to the corporation’s directors over the appropriateness of playing the song “Remember” on the radio so soon after the death of Albert Roberts. Attenborough was concerned that the track, a heavy-rocking number whose angry lyrics culminated in an exhortation to ‘Remember, remember / the Fifth of November!’, followed by the sound of an explosion, might be interpreted as a tacit endorsement of political violence. CBC directors agreed and commissioned their in-house producers to make a shortened ‘radio edit’, cutting off the explosion. Dick Crossman, who as domestic secretary held ultimate ministerial responsibility for the CBC, apparently regarded the episode with baffled amusement, writing in his diaries: ‘What are we coming to as a people if we are so unsettled as to be frightened of a children’s nursery rhyme?’

33: Of course, this is not to say that there were not frequent and notable exceptions. David Lewis himself was 58, while Maggie Roberts and Stanley Orme were two prominent opposition figures still in their mid-forties.

34: ‘Oxford Union’. OOC: A prestigious debating society in the city of Oxford, nominally independent from the university, whose membership is nonetheless mostly drawn from the ranks of the city’s student body. Prominence in the Union (which is not, despite the name, any sort of student or trade union) has often prefigured prominence in public life as an adult, and in recent times several prime ministers – most recently Boris Johnson – have been former presidents of the society. Roy Jenkins himself, our putative author, served a term as the Union’s librarian while at Oxford in the early 1940s. He ran for the presidency twice, both time unsuccessfully.

35: ‘Cymdeithas yr Iaith’. OOC: Cymdeithas have appeared before, in the second part of this chapter (see paragraph 7, image 3 and note 4 here). I have little more to add to the above, other than to add perhaps that on reflection my initial translation of ‘Cymdeithas yr Iaith’ as ‘Society for the [Welsh] language’, while more or less correct (though in hindsight I would swap ‘of’ for ‘for’) doesn’t quite capture the nuances of the word ‘cymdeithas’ in Cymraeg. Cymdeithas is a wonderful word whose ultimate origin stems from a proto-Celtic root that suggests a journey or travel (‘taith’, or ‘journey’ in modern Cymraeg is related), while the cym- prefix is cognate with Latin con- and denotes togetherness. Hence instead of the somewhat apolitical ‘society’, ‘cymdeithas’ might be more literally translated as something like ‘fellow(-traveller)ship’, which conveys more of a sense of its inherent mutualism. As an aside, I have recently finished reading Richard King’s excellent oral history ‘Brittle With Relics: A History of Wales, 1962-1997’ (Faber, 2022), which I would recommend to anyone interested in the real-life analogues, not widely known, of the autonomism debate in Echoes. There is a fair amount that I would write differently about my handling of the Welsh crisis in the last few chapters had I had the benefit of having read it before I embarked upon writing. Such are the perils of taking over three years to finish a chapter of an AAR.

36: For their part, the leadership of Cymdeithas refused to condemn the MAC arrestees outright. The trio’s history and members of the language campaign group naturally brought attention from the media and the authorities. Ffred Ffransis, the group’s chairman in 1967, gave a comment to the CBC in October to the effect that, while they and Cymdeithas may now differ in opinion over best strategy, it was clear Iorath, Wyn Parry and Griffiths still felt very deeply about the cause of ending Welsh subordination to government in Westminster. A poll conducted around the same time by the Western Mail, the principal English-language broadsheet for Wales and not a publication usually given over to sympathy for Welsh nationalism, found that 61 per-cent of respondents were broadly supportive of the kidnappers, with only 17 per-cent opposed to their actions. Clearly, there was little love lost among the Welsh for a man whom they had already condemned as a murderer for his role in the horror of Aberfan.

37: Llyn Celyn reservoir opened in 1965 following a lengthy planning and construction process whose origins stretched back to the last years of Mosleyite rule in Britain. Construction of the reservoir as proposed by the city corporation of Liverpool required the flooding of Capel Celyn, a Welsh-speaking village near Tryweryn in north Wales, and the displacement of its residents. Over the opposition of every single Welsh member of the Assembly, and in the face of vocal and sustained protest from people and groups across Wales, the government pushed through legislation to approve construction. The flooding of Capel Celyn and the displacement of its Welsh-speaking community for the profit of English councils was a major impetus for the formation of Cymdeithas yr Iaith in the early 1960s, and more generally for an initial surge in pro-independence sentiment in Wales prior to the more strongly remembered events at Aberfan and Deep Duffryn later on in the decade.

38: The presiding magistrate had initially fined the five defendants after finding them guilty both of strike law violations and contempt of court, though in a final act of protest the group had unanimously refused to pay. As a result, the magistrate sentenced each of the five to three months imprisonment.

39: ‘a community of nearly three million people’. Lestor here is referring, somewhat diplomatically, to Wales. Having later demonstrated herself a dependable ally of the autonomist cause during her career in government, it can be assumed that this circumlocution was used in favour of saying ‘nation’ or similar.

40: In real terms, the coalition had 164 more seats than the opposition, with 382 to 218. In practice, however, Popular Front member Michael Foot’s status as Assembly chair took his vote out of consideration in all but the most exceptional circumstances. Hence the government’s effective maximum voting strength without opposition support was 381. It goes without saying that these calculations assume full attendance at a vote, which was also not usually the case.

41: ‘hwyl’. OOC: Another lesson in the difficulties of translating Cymraeg. ‘Hwyl’ is at risk presently of joining cousins like ‘cwtch’ and ‘hiraeth’ in being taken as a twee borrowing into the English language, expressing something essential to the Celtic spirit that is powerful in ultimately evading the grasp of the anglophone. (Recently, the Welsh tourist board have decided to profit from this, inviting people to ‘feel the hwyl’ in their latest campaign to encourage visits to Wales, apparently hoping to ape the success of the Danish ‘hygge’.) A second dive into etymology might help strip back some of the wooliest sentiment. The word ‘hwyl’ is used metaphorically in Cymraeg to mean anything from ‘mood’ to ‘fun’ to ‘fervour’ to ‘progress’. ‘Hwyl fawr!’, ‘big hwyl!’, is the most common way in Cymraeg to say goodbye, commanding not that God be with you, but that you be blessed from within with great fervour and success. The word itself comes directly from the old Celtic for ‘sail’, and ‘hwyl’ still performs this function in modern Cymraeg. The connotation, then, is of an essential spirit that guides or pushes one forwards, and when one is absent from it one is adrift (‘anhwyl’ means ‘illness’). Certainly, one of the most common uses of the word is to describe a rousing political speaker; Nye Bevan would be the perfect example, but before him all manner of other union leaders and, in particular, Methodist preachers of the turn of the century would have exemplified the phenomenon. These days to my mind it retains something of this historical character first and foremost. But this is probably to be overly romantic about both the heights of our past successes and the depths of our recent difficulties.

The juxtaposition I make above with ‘chutzpah’ is not meant to imply synonymity, but in the differences between the two terms I would argue (reductively) that one could infer a not unhelpful starting point for the contrasts in Bevan and Lewis’s two styles.

42: Known to very few people at the time, perhaps only to Jennie Lee, Bevan underwent successful treatment for cancer in 1960 before he died of the disease seven years later.

43: OOC: Per Wiki, Michael Foot did indeed credit David Lewis with converting him to socialism while they were contemporaries at Oxford. Foot was a member of an established Liberal family, whose father Isaac had been a Liberal MP. If his brother Hugh is to be believed, the family’s politics owed themselves not to Marx or even the Fabians, but to Cromwell, Milton and the British nonconformist tradition.

Last edited:

- 2

- 1

Excellent to see this back. Please note the full italics for the second half of the chapter.

An interesting end for Lewis, and I'm not sure what happens next (aside from once again, trouble in German-backed Europe due to American-backed money troubles). Portugal coming into EuroSyn, and the 80s being a more prosperous decade seems promising. I can only imagine North Sea oil and gas helped out a lot with that.

An interesting end for Lewis, and I'm not sure what happens next (aside from once again, trouble in German-backed Europe due to American-backed money troubles). Portugal coming into EuroSyn, and the 80s being a more prosperous decade seems promising. I can only imagine North Sea oil and gas helped out a lot with that.

- 2

Many thanks, Butterfly. Good to be rounding this saga off at last.Excellent to see this back. Please note the full italics for the second half of the chapter.

I think I’ve managed to correct the italics; looks like me trying to put the characters ‘[ i ]’ without spaces in a piece of quoted speech halfway through messed things up. Let me know if it’s still bugging, though.

Glad you found it interesting. I’m fairly satisfied that it ties up enough loose ends while leaving the general sense that this is an uncertain moment for the Commonwealth. I’ll do a brief (and I do mean brief) epilogue on the Lewis chapter to give a few more hints of how his reputation falls longer term, then I plan one last chapter in a similar vein that will gloss what happens for the rest of the Sixties, but after that we are in uncharted territory. Despite my ill-fated confidence thirteen months ago, I’m not sure what the next take from this universe quite looks like yet. But I’m sure I’ll come up with something. Some of my favourite characters have only just been introduced, and the itch remains to be scratched.An interesting end for Lewis, and I'm not sure what happens next (aside from once again, trouble in German-backed Europe due to American-backed money troubles). Portugal coming into EuroSyn, and the 80s being a more prosperous decade seems promising. I can only imagine North Sea oil and gas helped out a lot with that

As for Eurosyn and wider Europe, as ever you are broadly on the money. @99KingHigh and I discussed years ago having Germany as the only nation really shafted by Nixonomics (Nixon wins that election, btw - not sure if anyone remembers that), mainly because it would be quite funny. The Seventies will be a time of realignment and cautious rapprochement, and the Eighties should obviously benefit from that.

- 2

- 1

I think I’ve managed to correct the italics; looks like me trying to put the characters ‘[ i ]’ without spaces in a piece of quoted speech halfway through messed things up. Let me know if it’s still bugging, though.

Fixed.

As for Eurosyn and wider Europe, as ever you are broadly on the money. @99KingHigh and I discussed years ago having Germany as the only nation really shafted by Nixonomics (Nixon wins that election, btw - not sure if anyone remembers that), mainly because it would be quite funny. The Seventies will be a time of realignment and cautious rapprochement, and the Eighties should obviously benefit from that.

EuroSyn is a really good idea, and it exapnding is a great sign. Syndicalism works a lot better in view of a united European bloc than capitalist states do, and with it starting before the founding states deindustrialised, they can control their expanding tech, electronic and specialised heavy industries develop, and have a standard set too. Germany, being full of socialists as much as any other country, will be looking at this and going - wait, why do we keep letting ourselves be an American puppet again when we can be one of the leaders of this better group?

The bloc then getting its own huge oil and gas supply in the Commonwealth right at the point where high-grade electronics really take off (and need the power to run) would be a colossal boost. The Commonwealth getting the chance to do a Norway-style national sovereign grant with an entirely nationalised oil and gas industry would obviously help itself quite a bit too...speaking of, what's the status of Scandinavia? If Norway can be tempted into the bloc, then even more energy security comes into play.

- 2