128 Days: The Decline and Fall of Bevanite Britain (I)

128 DAYS

The Decline and Fall of Bevanite Britain

Gwyn Alf Williams, 1980

(I)

On 19 September 1966, Aneurin Bevan marked his fifth year as Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Commonwealth. The anniversary allowed a small pause for reflection as Britain lurched from a dissipating crisis abroad to a brewing crisis at home. Oswald Mosley’s sudden exit from power in 1961 had come after a turbulent final few years as premier, characterised by widespread dissent and marred by equally violent political repression, all unfolding in the aftermath of the terrible industrial disaster at Windscale. Britain at the turn of the 1960s was a society whose patience with established authorities had worn exceedingly thin; the youth were virtually united against the regime, and public displays of force to counter the dissident threat soon did for the appetites of all but the most ardent of Mosley’s apologists. Within this climate, Aneurin Bevan emerged as a unifying figure, whose appeal extended uniquely to both government insiders and the opposition. In the legislature, he had cultivated a following of reformist ministers and Assembly members, and in the country he was recognised as a principled defender of socialism against Mosleyite excess. More still, he was a genuine hero of the revolution.

When Bevan’s long march to power finally brought him to the premiership at the close of the long 1950s, the task which faced the reformists was considerable. But Bevan was a known fighter, and even though he was only months away from his 64th birthday, he had the confidence of a vocal majority, and his mandate for change was undeniable. First in the firing line were the illiberal institutions that had grown up under Mosley, which the old regime had relied upon in its disastrous attempts to guard itself against its critics. Bevan’s thaw promised ‘syndicalism with a human touch’, and after 1961 a grand campaign against the callous Mosley-era bureaucracy began in earnest. The managerial class, that great bugbear of the post-revolutionary left, was cut down to size in light industrial sectors in the 1962 budget, giving back more controls over production to the shop floors. Meanwhile, stringent curbs on union powers were lifted, with the two-thirds majority on strike ballots being abolished in June 1963, in favour of a return to the simple majority. This set the tone for the Bevanite industrial consensus, which valued above all things cooperation between the state, the unions and the workers, believing that each had a role to play in the overall management of the economy. By the middle of the decade, this ‘softly softly’ strategy began to show appreciable results. Days lost to strike action halved between 1959–63, plateauing thereafter until 1966, and an end to strict Mosleyite planning gave rise to a moderate increase in labour productivity year on year during the period 1962–67.

This is not to say that the ‘Bevanite’ economy was a clear case of ‘bread and roses’. After 1961, the new government remained committed to the idea of Britain as a heavy industrial power, influenced in no small part by Bevan’s own history as a miner. Sceptical of the half-hearted push towards consumer goods attempted by the Mosley regime in its last years, Bevan was wedded to the supremacy of the traditional ‘commanding heights’ of the British economy: utilities, transport and infrastructure, other heavy industry and, most importantly, the mines. Government investment in these sectors increased at the expense of Mosley-era modern manufacturing (with the exception of the computing industry in and around Manchester, a lodestone in Bevan’s embrace of the ‘white heat of technology’). Broadly, money flowing into these areas ended up in two areas: improved plant, and developments in education and training. In this sense, although undoubtedly reformist Bevan’s project was ultimately a conservative one. His overriding concern, nobly, was for job preservation, and he shared the trauma over unemployment inherited by all in his generation who were veterans of the labour crises that had precipitated the 1929 Revolution. This trauma expressed itself in a near total refusal to touch the system that underpinned the British economy, instead tinkering about the edges and ‘modernising’ where modernisation could be achieved without too much fuss.

Robert Skidelsky once summed up Bevan’s attitude to his Mosleyite economic inheritance as ‘seven parts good, three parts bad’. The two rivals agreed on a number of things (after all, Bevan has signed Mosley’s ‘Birmingham Manifesto’ of 1928 that had led the pair out of the old Labour Party). Paramount among the shared tenets was a commitment to ‘productivity’, managed technocratically by, firstly, the massaging of labour relations and, secondly, a proactive involvement with research and development. Where the two men differed was in their opinions of the specifics of the management. Although a reformist, Bevan remained a centralist. His objection to the managerial class was ideological, not logistical, and while he viewed centralised managers as a barrier to the proper exercise of democracy in the workplace, his alternative system was not the total devolution advocated by anarchist-influenced groups in opposition. As is suggested by the overall pattern of ‘Bevanite’ economics, the eventual outcome was a half-measure. Liberalising measures implemented in light industrial sectors saw shop stewards given many of the former responsibilities of the managers in dealing with central planners (note that they did not receive final autonomy), but these reforms were not reflected in the ‘commanding heights of the economy’, where workers remained tied to directives from Whitehall. Thus it can be said that Bevan was happier than Mosley to take authority away from the technocrats and give it to the workers in order to ensure smooth industrial relations, but on the whole neither man deviated from the ‘joint consultation’ approach to labour solidified after 1950. At the same time, as we have already seen, Bevan’s preferences differed from Mosley’s on matters of industrial investment without representing a fundamental break with the system of central management.

Oswald Mosley, during his retirement.

Later, the former chairman would claim that ‘Nye Bevan was my proudest achievement.’

Before continuing to the meat of the story of the end of Bevanism, it serves well to note two things. First, considering the extent to which it has become the fashionable topic du jour of our own economic debates, it is important to recall that neither Mosley nor Bevan held growth to be the aim of their economic policy. Rather, the desired outcome of centralist management and a deep concern for productivity was competitiveness – particularly insofar as this meant keeping pace with the advancing economies of Central Europe. Since the formation of the Eastern European Economic Co-operation Zone (ECZ) in 1953, the importation of American-style industrial methods and the injection of American capital had fostered buoyant economic conditions in the German bloc, coinciding with a shift away from agriculture in Mitteleuropa. An initial period of stop-start progress during the MacArthur presidency gave way in the aftermath of the January War to a profound American interest in cultivating its European alliances. President Kefauver and his secretary of state J. William Fulbright recognised the benefit to be had in building up the Reich as a ‘prosperous and stable ally’, and soon the conditions were manufactured for a German-led economic boom. In August 1957, the six-month Conference on German External Debts ended with the writing down of German debts by 46 per-cent, from DM13.5bn to DM7.6bn. At the same time, the Reich acceded to the Amsterdam Conference dollar area on a highly favourable exchange rate, sparking an export boom in Central Europe. $20bn of US private investments followed and, thusly remade in the American image, the Reich and its satellites became the very model of capitalist productivity. So successful were the Democrats in their project that by the 1960s even the US market was being flooded by cheap cars and other consumer goods from Central Europe (above all Germany), sparking the terminal shift of the American economy away from manufacturing.

Many of the conditions that had sparked the ECZ boom were absent from the British situation. Leaving aside the injection of American capital, the Commonwealth no longer had a mass agricultural labour force which might be conscripted into service to fuel an industrial boom[1]. Britain’s manufacturing base was well established – although in truth it had been in decline since well before the Revolution, arguably beginning to lose its edge as early as the 1870s. By capitalist parameters (from which, after all, he hardly deviated), Mosley’s economic system had proved robust, and Britain had enjoyed thirty years of solidity. To those who accepted uncritically Mosley’s own crisis-era bromides that cast his system as a great panacea, its ultimate demise might have seemed unheralded. Anyone who remained familiar with the Marxist critique would have seen things alternately for what they were, and Mosleyism’s final exposure as a bandage for capital would have come as no surprise. Like all capitalist systems of production – and I include under this umbrella the statist systems that retained a hegemony in Britain until very recently – Mosley’s system was never sustainable. Neither, therefore, was the revised Bevanite application – and neither, for that matter, were the German or American systems, whose own crises followed after the crisis of ‘British syndicalism’ with only a brief delay. All of these systems shared many similarities, and it is not unreasonable to insist that the crisis period that buffeted the industrialised world in the third quarter of the century was as much as anything a crisis of capital. Bevan’s great misfortune was that Britain, who had industrialised early, would be made to run the gauntlet first.

German financiers signing the Amsterdam Agreement, 1957.

Secondly, it remains important to note those areas in which Bevan can be said in the end to have found success. While a thorough critique of the insufficiencies of the Bevanite project is always worthwhile in evaluating the historical course of the Revolution, we must be careful not to throw out the baby with the bathwater. It is easy in hindsight to say that Bevan did this or this incorrectly, or that he was too hesitant in pursuing that policy or another, but we must recall the trauma of the immediate years after Mosley’s own fall. In 1961, the organs of the British state verged on sclerotic, and the economy was in a perilously overheated state after five years of desperate fiddling by Mosley and Harold Macmillan. Although not a success on their own terms, Bevan’s economic reforms deserve some share of the credit for averting the total collapse of the British system as it had calcified under Mosley. Additionally, without the significant investment in infrastructure, research and training undertaken during the Bevan era, the subsequent road to reform and recovery would have been undoubtedly a great deal more arduous. We still benefit from Bevan’s schools and hospitals, and signs of his touch remain visible across our railways and roads. This is to say nothing of the liberalising campaign embarked upon by his government, which demonstrably improved the lives of millions of previously persecuted men and women across the Commonwealth. All things considered, while there is a great deal which remains rightly discredited, there is much to admire about Bevan’s ‘human touch’ syndicalism.

Bevan’s greatest shortcoming as a reformer was, perhaps, a failure to carry on his great redefining project for syndicalism into the economic sphere: to refashion it as something beyond Keynesian corporatism. Bevan’s opponents, on both the right and the left, were those who could envisage changes to the British economy that took it beyond this faltering orthodoxy.

**********

1: Even among the fraternal syndicates, Britain was somewhat unique in this. France’s economic troubles did not become fully apparent until the mid-1970s, and the advancement of both the Spanish and the Italian economies are only now showing signs of slowing down.

Changing of the Guard

Over the 1966 summer recess, the Bevan government received bad news. Wal Hannington, the 69-year-old President of the Commonwealth and the only self-described communist in the cabinet, was gravely ill. By the end of August, he was dead.

It would be inaccurate to say that Hannington had been one of the great survivors of Commonwealth politics – men like Bob Boothby and, to be sure, Nye Bevan himself, whose combination of politics talent and a willingness to compromise allowed them to remain in positions of prominence, if not always great power, while all around others came and went. Boothby was undoubtedly the most successful practitioner of this dark art; even when he was sidelined during the years 1957–62, such was his standing that Mosley had to grant him chairmanship of the new Executive Council of the European Syndicate in order to be rid of him. It was a sign of his equal importance to Bevan, having gradually – and fatefully – come over to the side of the reformists as the 1950s progressed, that his departure from office in Lyon necessitated his accommodation in the new Commonwealth government, and as Fenner Brockway’s successor at the International Bureau after 1963 he was a key figure in charting Britain’s course between the many and diverse crises of the next three years. This, having once been Mosley’s most trusted lieutenant, and without doubt Mosley’s most favoured successor had paranoia not got the better of him in the final years of his reign.

Nye Bevan, from a 1963 election poster.

Bevan’s survivalism was altogether a different proposition, founded as it was on a base of his own considerable sense of conviction. Had he never achieved the highest office, Aneurin Bevan would no doubt have gone down in the political history of Britain as one of the most formidable practitioners of the art of opposition ever to have graced the halls of Westminster. Perhaps the greatest orator of the revolutionary generation, certainly after the murder of Arthur Cook, Bevan’s charisma was rivalled only by Mosley’s, which of course was what made him so dangerous in the eyes of the chairman. That he could never fully be brought to heel by the Mosleyites only aggravated matters, and Bevan’s power base in the Assembly – and later in the cabinet itself – presented Mosley with the most serious threat to his position. (Unlike the tens of thousands who took up their opposition on the streets, Bevan could not be dealt with by brute force.) It was perhaps only ever a matter of time before the Bevanite coalition pulled the rug from under Mosley’s feet, abetted and given validity by the undeniable power of the public opposition movement in the country. Governing was a much different challenge, and perhaps one that Bevan came to too late, already fatigued by years of work challenging Mosley from behind the scenes, but it cannot be denied that he had triumphed over the odds in getting to a governing position at all.

Wal Hannington’s story was by no means as public as either Bevan’s or Boothby’s, but this is not to deny its importance. Forced out of power in the aftermath of the Troubles in 1934, Hannington – who by the age of 37 had already served as Chairman (1931–32) and President (1933–34) – returned to his original trade as an engineer. A card-carrying member of the CPGB, he was subjected to the same sorts of harassment as much of the left opposition during the 1940s, although he still managed to complete a term as national organiser of the Amalgamated Engineering Union from 1939–47. When the government curtailed the powers of the independent unions and forced much of the left underground after the industrial disputes of 1946–50, Hannington left public life, continuing on in his engineering job and staying active within the Communist Party as a writer on current affairs. In the early 1950s he published a number of short biographies of revolutionary period leaders via Victor Gollancz’s underground press, and in 1957 he authored a monograph on the ECZ that warned against the expansion of capitalism in Eastern Europe, although stopped short of outright Soviet apologism. Hannington, it must be said, was never a member of the New Left tendency which emerged from the lean years of the late ‘50s, arguing for the necessity of independence from Moscow in the formulation of British communism. It is possible that Hannington was simply not predisposed towards these sorts of debates. Always a committed trade unionist rather than a CPGB doctrinaire, having led a movement of millions of unemployed men and women as a young man during the Revolution, it is perhaps understandable that Hannington never felt overly impressed by the dogmatic disputes endemic to the Marxist–Leninist left. Certainly, he did not seem to have been too badly affected when CPGB General Secretary Rose Cohen expelled him from the party following his decision to accept Bevan’s offer of the presidency in 1961.

Wal Hannington, 1929.

During the Bevanite period, as during the Mosley era before it, the presidency was an ill-defined and somewhat awkward role. Officially the Commonwealth’s head of state, the only widely agreed upon function of the presidency was to represent Britain abroad at official state functions. Per the 1929 constitution, the president, like the chairman, was elected by the People’s Assembly to act as a sort of ‘guardian of the revolution’. In theory, under its 1929 powers the presidency was to act as a brake on the chairmanship, invested via the Assembly with the ‘will of the people’ and able to take action – ie to remove the government – should the government begin to act maliciously. In practice, the 1929 constitution had produced only a hesitant ministerial gavotte in the years before its first failure in 1934, with the CPGB leadership exchanging roles annually amongst itself while governing according to a shared party line. The result was as intended, with one infamous exception, preventing power from accumulating in any one place during the post-revolutionary reconstruction period. When the exception proved fatal, leveraging his staying power to assume control of government in the aftermath of the failed counter-revolution of 1933–34, he was quick to refashion the constitution after his own ideal. Doing away with annual reappointment, Mosley’s government had a more authoritarian character from the start – although it was only after 1939, at the height of his powers following the successful conclusion of the Spanish War, that he was able to begin excluding rivals in earnest. The presidency, previously reserved as a sop to national unity, was now fused with the regime. Cynthia Mosley was always more of a convincing socialist than her husband, but few could help but question the appropriateness of a conjugal relationship between president and premier. After he death, Mosley’s assumption of the office pro tempore all but confirmed the inevitable: that this supposed check on the executive was indeed toothless, and that the regime no longer had any reason to disguise its totalising ambitions.

Some hint of a return to the old national unity character had been apparent since 1957, when Mosley had hoped to rid himself of his Bevanite problem by promoting Bevan out of harm’s way into the presidency. This strategy failed, and the office once again proved capable of holding power away from the executive, even if it was yet to reacquire any sort of significant, constitutionally useful role. This was the office as Hannington found it. Bevan’s choice of an old revolutionary hero as ‘guardian of the popular will’ was of course loaded with significance, presaging the depth of his reformist ambitions even if not their eventual profundity. But after this, Bevan’s reformism barely touched the presidency, preferring to address the more egregious problem presented by the ossified People’s Assembly. While the Assembly, formerly the crucible of the Bevanite resistance, was finally granted political power in fact as well as in theory, President Hannington remained a figurehead. Any state-minded democrat would agree that this was no bad thing – the most power should go to those who are easiest for the people to get rid of – but it did not solve the question of what the presidency was for. Crowded out by other, more pressing tasks, the Bevan government was never able to come up with an answer, and the head of state issue was left untroubled.

Cynthia and Oswald Mosley, photographed during the 1928 UK general election.

It seems cruel, therefore, to suggest that the greatest impact Hannington had on the course of the Bevan ministry was in his death, but the suggestion is perhaps not so wide of the mark. The former president died shortly before the Assembly returned from the long summer recess, reconvening for what would be its penultimate session before the next election in May 1967. In accordance with the constitution, Assembly chairman Ian Mikardo was sworn in as Commonwealth president pro tempore, and neither the ministry nor parliament had any complaint with his temporary occupancy of the role lasting until the election. This set in motion a ministerial reshuffle. Mikardo, a Bevan ally and a member of the LUPA, was succeeded in the Assembly chair by Michael Foot, an adroit promotion that rewarded the Popular Front with a key role while keeping it in the hands of a Bevan loyalist. The relative under-representation of the Popular Front in the government had been an issue of quiet contention within the coalition since its re-election in 1963; the party held 46 per-cent of the government’s seats in the Assembly, but occupied only three out of fourteen cabinet positions. Government remained dominated by the old reformist core of the LUPA, and having been forced into a reshuffle Bevan was under pressure from his coalition partners to redress the balance of power. Resultantly, Popular Front leader David Lewis, a Bevan ally since 1954, was promoted to the directorship of the Office for Economic Co-ordination at the expense of Bevan’s wife Jennie Lee[2]. Lewis was also given the new title of deputy chairman. This brought with it no additional responsibilities, but seemed to suggest a formalisation of the Popular Front’s considerable influence in government. With many of Bevan’s key party allies now in their sixties, it also opened up the possibility of the relatively youthful Lewis (he was 57) taking power for himself in the near future.

Beyond this sort of political speculation, Lewis’s enhanced prominence brought with it more immediate implications. The Bevan cabinet was notable for the fact that it included two married couples, and just as Bevan himself was matched by Jennie Lee, David Lewis was joined in power by his wife Barbara. Barbara also benefited in the reshuffle, taking over Michael Foot’s old brief of employment. This was significant in that it placed management of the Commonwealth’s economic policy almost entirely under the control of the Popular Front, leaving the LUPA with control over domestic and social services. A PF-led economic department represented an unmistakable shift away from the Bevanite orthodoxy; albeit tentatively, the Lewisite position within the Popular Front was not afraid of speaking openly about seeing through economic reforms to match the government’s liberalising social agenda. From Lewis, this was no idle suggestion; he had overseen a vast majority of the liberalisation programme as Director of the Domestic Bureau after 1961, and even if it seemed unlikely that the government would change course too greatly before the election – the Bevanites had after all retained their strong cabinet majority – once again the possibility was left very open.

David Lewis, the new Director of the Office for Economic Co-ordination and Nye Bevan's deputy chairman.

What was the economic situation that greeted the new ‘Lewisite’ ascendancy? The question of productivity we have already given some thought to, but this was not the whole picture. The ‘scientific’ account of the productivity debate, that which is concerned by management efficiencies and technological improvement, was prevalent among the Bevanite planners, but David Lewis did not share in the enthusiasm for this sort of thinking. Lewis stuck to an alternative view, which held that productivity was fundamentally a matter of labour relations. British competitiveness was held back not by any technological gap between the syndicalist and the capitalists worlds, nor any fundamental differences in respective methods of production, but, he believed, for the simple reason that both the planners and the union bosses were too greatly concerned about preservation, and not enough concerned about innovation. As things stood, the Commonwealth could never compete with the ECZ because the Mitteleuropeans operated in a climate that prized innovation (or, more properly, growth) over consensus, which was a drag on productivity. Lewis’s guiding belief was, frankly put, an insistence that enterprise was not a dirty word.

Although his commitment to planning was not in doubt – and it should be said that he had no quarrel with Bevan’s ‘commanding heights’ policy – planning for Lewis was corrective and not directive. He believed that the role of the state was to correct inequalities opened up by free enterprise, but he did not take the fact that this was the case to be indicative of the wrongness of free enterprise in the first instance. At the end of 1966, this was an idea that spoke more to the emergent social-democratic opposition tendency than it did to the government view, and a hard-headed sense for politics kept Lewis from giving too much away about his predilections for economic liberalisation. But action required no words – least of all from a man who pointedly reminded his party at conference in late September that ‘power [is] not a Sunday-school class, where purity of godliness and the infallibility of the Bible must be held up without fear of consequences.’ Before long, he would have the chance to put this ethos into practice.

**********

2: Lee became Secretary for Education, succeeding Dick Crossman who took over David Lewis’s position as Director of the Domestic Bureau. While strictly this represented a demotion, Lee was active in championing the Open University programme launched by Crossman in 1964, and her great plans to expand it pointed towards an enthusiasm for her new role that was never entirely present with the economic brief.

‘Like A Scene From Hell’

On Monday 31 October, 1966, CBC 1 was scheduled to begin transmission, as it did every weekday, with three hours of programming from the Open University. That morning, the schedule included a lecture on computing, a documentary film about the history of enclosure, and a performance of music by Ralph Vaughan Williams. It was, by all measures, an unremarkable beginning to the day.

At noon, the rest of the day’s programming began with the news. The bulletin was presented that day by Brian Redhead, whose talent as a news broadcaster was founded on an ability to deliver serious journalism in a relaxed, almost amiable manner. That Friday, any hint of this amiability was nowhere to be seen. This was the first indication that something was gravely wrong.

Brian Redhead.

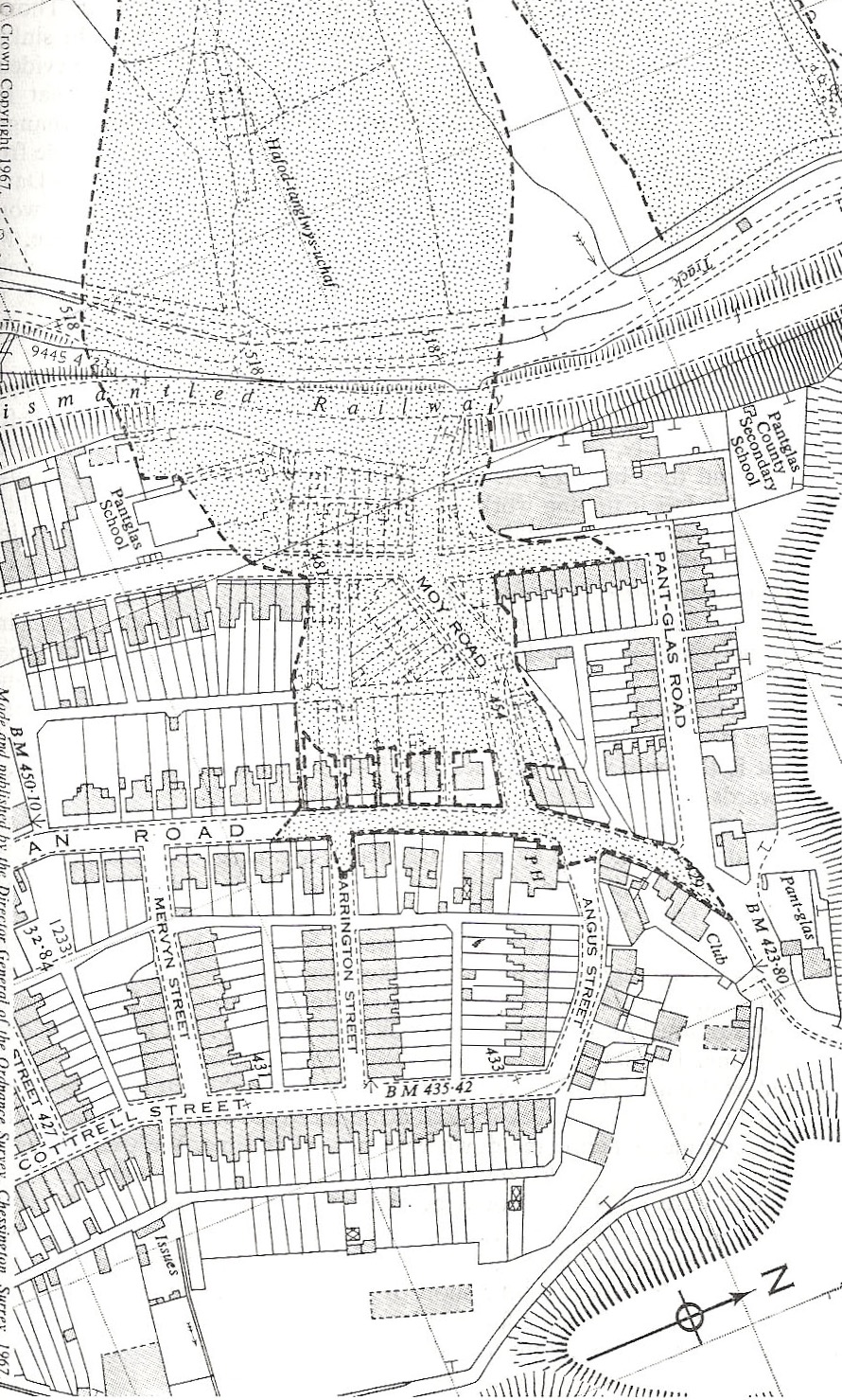

Redhead proceeded to announce, sombrely, that a fatal mining accident had taken place near a village in South Wales. Earlier that morning, shortly after 9 o’clock, a spoil heap at the Ynysowen colliery near Merthyr Tydfil had collapsed, after being saturated by water during a period of heavy rainfall. The heap turned into a slurry, which slid down the banks of the Merthyr Vale towards the village of Aberfan. Within minutes, a whole section of the village had been covered in over 40 thousand cubic metres of debris. Two farm cottages, 18 houses and the Pantglas Junior School – where children had only that morning returned after the half-term holiday – had all been destroyed. The number of casualties remained unknown, but it was feared that the toll would be catastrophic. 36 people – including 27 children from the junior school – had already been rescued from the debris and were rushed to hospital, but as the morning wore on fewer and fewer survivors were found. By 11 am, rescue efforts had turned into a mission to recover the bodies of the dead.

1964 image showing the spoil-heap tramway at the Ynysowen colliery.

Pantglas Junior School is visible on the left of the image.

The first CBC reporter on the scene of the disaster was John Humphrys, at that time a young journalist with the corporation’s Welsh arm. He appeared on television visibly upset, describing what he saw as being like ‘a scene from hell’. Millions watched as CBC cameras showed the miners of Ynysowen, raised from the coal seams, digging through the spoil in search of the missing, working meticulously to ensure that their excavations did not lead to further collapse. They were helped by local residents, who had rushed to the junior school with garden tools and, in many cases, their bare hands, to help move the rubble. Around the diggers, ambulance workers, fire fighters and Workers’ Brigade volunteers all worked to help bring the situation under some sense of control. Engineers from British Coal worked to dig a drainage channel to help stabilise the tip, which had been further saturated by the destruction of two water mains during the descent of the spoil into the valley. While they worked, residents of all surviving houses in the west of the village – the side closest to the spoil tips – were prepared for evacuation in case of another collapse, although by 2 pm the tips were stabilised without further incident. Persistent rainfall meant that the threat of another catastrophe was not fully alleviated, but immediate danger had passed. It now fell to the rescue teams, the politicians and – most poignantly – the surviving residents to process the scale of the tragedy.

Map showing the extent of the slippage as it covered a section of the village of Aberfan. The debris is marked with the dotted hatch.

Ysgol Gynradd Pantglas is visible in the left-middle of the map, the east wing entirely submerged.

Over the course of the afternoon, various government ministers and other dignitaries began to arrive in the village. The first to make it over from Whitehall was Peggy Herbison, Director of the Bureau of Coal and Steel, who visited the scene of the disaster at 4 pm. Of all members of the cabinet, Herbison was perhaps uniquely well-placed to be sympathetic to the plight of the Aberfan residents. Growing up in Lanarkshire with a father who had been a miner and militant unionist, Herbison was no stranger to the perils of the coal industry. As a former teacher, she was also acutely sensitive to the pain of the Pantglas school community as they came to terms with their loss. Herbison heard reports from British Coal engineers engaged in the clean-up operation, then met with members of the local council from Merthyr Tydfil, who were already involved in the work of setting up a disaster relief fund, for which she pledged government support.

Herbison remained in Aberfan until shortly before 9 pm, when Chairman Bevan arrived at the scene for himself. Over the coming months, Bevan’s own role in the events leading up to the disaster would become the subject of great controversy. As more details of the catastrophe became known, the fact that such a thing could have happened under the watch of a Welsh premier – and a former miner, no less – would assume much significance, particularly in the eyes of the burgeoning Welsh autonomist tendency, but this was all to come. On the day of the disaster itself, Bevan remained a popular figure, and his very sincere displays of devastation at the sight of the damage did go some way to reassure the survivors that, in spirit at least, they were not alone in their grieving.

“Never in my life have I seen anything like this. I hope that I shall never ever see anything like it again.”

The power of that sense of shared grief which came out of Aberfan and spread across the Commonwealth should not be denied. As news continued to disseminate from Merthyr Vale, it soon became clear to all onlookers that this was no ‘ordinary’ tragedy. Memories of the fire at Windscale nine years prior, which had sparked mass public anger directed against the Mosley regime without so much as one fatality, soon resurfaced, and it would not be overly exaggerating the matter to state that, in a sense, the disaster had struck a fatal blow at the very heart of the idea of the Commonwealth. Here was a state whose entire organisation, so we had been led to believe, was geared to serve and support the welfare of the workers of Britain: that they would be secure and safe in their jobs; that they would not want for food nor shelter nor comfort, and that, in time, their children would inherit a world where all these things and more were true. Expressed in these terms, the unforgettable image of Ysgol Gynradd Pantglas engulfed in thousands of tonnes of colliery spoil became a terrible metaphor, insulting in its directness, for the collapse of a system which had failed the very people it was conceived to protect. When CBC TV journalist Cliff Michelmore, giving an eyewitness account on the night of the disaster, expressed a hope that never again in his life would he see anything like what he saw in Aberfan, it came across as the message of a people crying out for change. A fundamental bond of trust had been broken between the state and the people, and now there could be no going back.

. . .

Last edited:

- 4