Chapter Fifty-one: We’re Not Dead Yet!

(February 1945)

PLA infantry conduct another human wave attack on Polish positions in Ganzi, February 1945.

=

==

==

==

Canada

Endurance in quiet desperation still marked the Allied experience in Canada in early February 1945. Six separate pockets and enclaves in the east and west of the country saw the grim fight for survival continue, each with differing supply circumstances and prospects and with ten of thousands of Allied troops facing the likelihood of eventual destruction or surrender.

By 4 February, Halifax held 22 Allied divisions and was holding comfortably enough for now against incessant American attacks. In Newfoundland, a German attack had pushed across the narrow strait from the last Allied-held port.

Four days later, the three separate pockets (Hudson, Great Plains and Rockies) in the west still fought on quite strongly against American attacks, though they were being gradually squeezed in on themselves. However, by the 12th the Hudson pocket had been reduced to just two surviving divisions, both badly weakened. And by the end of 14 February, these last holdouts had surrendered.

There was some better news in the east though: on the morning of 17 February the German attacks in Newfoundland had cut off four US divisions in the south-western part of the island, where they now had no supply lines. The Germans and British were also building up forces in the south of Labrador.

In western Canada, on 22 February the Rockies pocket, the largest of the two remaining enclaves, had just been constricted again in the south. The continued US attacks had now gained the upper hand, as the large Allied concentration of divisions was bereft of supplies and perilously low in strength and organisation.

The same day in the east saw two wildly different situations developing. The Allies had driven south from Labrador to further cut off the US pocket in Newfoundland and had also broken out in the north, around the flank of the American line.

In Halifax, however, for reasons that remained unclear to Poland the long and heavily held defence had suddenly begun to fail. The Allies there were on the brink of losing their sole port and supply lifeline, endangering the whole large lodgement that had been pouring in there in past months.

Four days later, the German push west from Labrador was gaining momentum, while one of the trapped US divisions in Newfoundland had been destroyed and the other three were in retreat.

Against expectations, the other two Allied pockets in western Canada were still holding on at that point.

The following day though, the feared news of Halifax’s fall was received. A desperate counter-attack was being conducted, but its prospects seemed poor. Over 20 Allied divisions, many of them still in good fighting order, were now in danger of isolation, supply starvation and destruction.

By contrast, the last stages of the Newfoundland encirclement were almost complete, as German troops launched the last attack against the hastily retreated and beleaguered Americans in the south-west corner.

As February ended, in the west (24 divisions) and centre (11 divisions) the last two pockets still survived, even as both were shrunk down almost to the last stand.

In the east, the Battle for Newfoundland was almost over, with the defending US division in the south-west defeated and surrendered, while two more tried to retreat before the province was occupied by the advancing Germans and they too were forced into captivity.

While the Allies were holding strongly enough for now west of Halifax, their counter-attack had failed and the Americans now had six divisions in place to hold the port. The many trapped Allied divisions seemed doomed to another slow and painful last stand and likely destruction.

=======

Mexico

Late on 1 February, the US amphibious assault of the west of the Yucatan peninsula had been defeated. A few days later, the US lodgement on the north had also been removed, with the trapped US division there forced to surrender on the morning of the 4th.

In the west and centre of the main Mexican front, The German Tijuana-Ensenada enclave still held out as a growing push up the Baja peninsula gained speed. On the morning of the 2nd, the US division cut off in the middle of the Baja was defeated and surrendered to German armour and infantry.

In the centre, US forces were still trying to push on further south from Juarez, against stubborn Allied resistance.

By 5 February, the whole of Baja had been reoccupied by the Allies, relieving the encirclement of Tijuana-Ensenada, though Tijuana itself was under US attack again. The rest of the Mexican front was quiet as US attacks ceased for the moment.

A relative lull followed for the best part of two weeks, until by early on the 19th Tijuana was set to be lost, but a narrow Allied salient had been driven through the centre of the US lines all the way to the Rio Grande, with Juarez falling to Yugoslavian heavy armour. The whole picture on this front had now changed, with the US line now looking rather thin in places.

Tijuana would be lost by the afternoon of 21 February, with an Allied counter-attack from the now heavily reinforced Ensenada (10 divisions) being made, though its prospects were not looking that good. Of interest, a Filipino division, the 83rd, was spotted in the southern US, sitting in front of the Yugoslav breakout around Juarez. The Allies had also closed up to the Rio Grande three provinces deep from its mouth on the Gulf of Mexico, with little in the way of US defenders in front of them.

Allied supply remained broadly adequate in most areas and a small bridgehead across the Rio Grande had been secured by Yugoslav infantry by the 23rd, though not in strength. It would later be driven back.

By the end of the month, German and British forces had crossed the Rio Grande in the south-east unopposed. The central Allied salient was still on the south bank of the Rio, but had been widened as US forces in the centre and east were being driven back. The Baja front seemed to have achieved temporary equilibrium, both sides having consolidated their defences.

With large Allied reserves massed to the south, the thinness of the US lines on the front seemed inexplicable – if welcome – to the Allied Supreme HQ in Mexico.

The Allied enclave in Guyana had held out all month, trading attacks with their US besiegers, remaining holed up in Cayenne.

Overall, the month had been ones of ups and downs for either side. The Canadian holdouts were still diverting considerable US attention, with some small scale successes in Labrador and Newfoundland and promising signs in Mexico being balanced by the slow strangulation of the remaining Allied troops cut off in the west and the surprising loss of Halifax.

South-West Pacific

The month opened with two Japanese invasions along the north coast of Papua, attempting to cut off the Allied divisions that had closed up to the Japanese defenders in western Papua. One division had got ashore in the jungle to the north by 6 February, but another attempt by two divisions to take the key port of Hollandia had run into a strong Allied garrison and was being held off – led by a Hungarian commander!

By the 7th, the Japanese landing at Hollandia had been fended off, but the Japanese had landed another two divisions in the vacant province to its west, where an Allied attack had now begun, as another was made by the French on the western lodgement.

Four days later, the two Japanese divisions west of Hollandia had been defeated and were retreating west, as a British division had reinforced the French attack on the west of the enclave, which was close to succeeding. By 12 February, all three Japanese divisions had been destroyed and the north coast secured again.

This sector remained quiet for the rest of the month, with a point of interest being the landing of a Korean division at Wewak (more on that below). They were at sea again as the month ended, with the front line in West Papua all tied up and a large Allied reserve holding Hollandia and another at Wewak: maybe they had decided that further Japanese landings were a distinct possibility.

Given the Japanese appeared to have no port to resupply their five divisions in West Papua, whose supplies seemed to be running out, this ‘starving out’ strategy by the Allies might prove successful.

=======

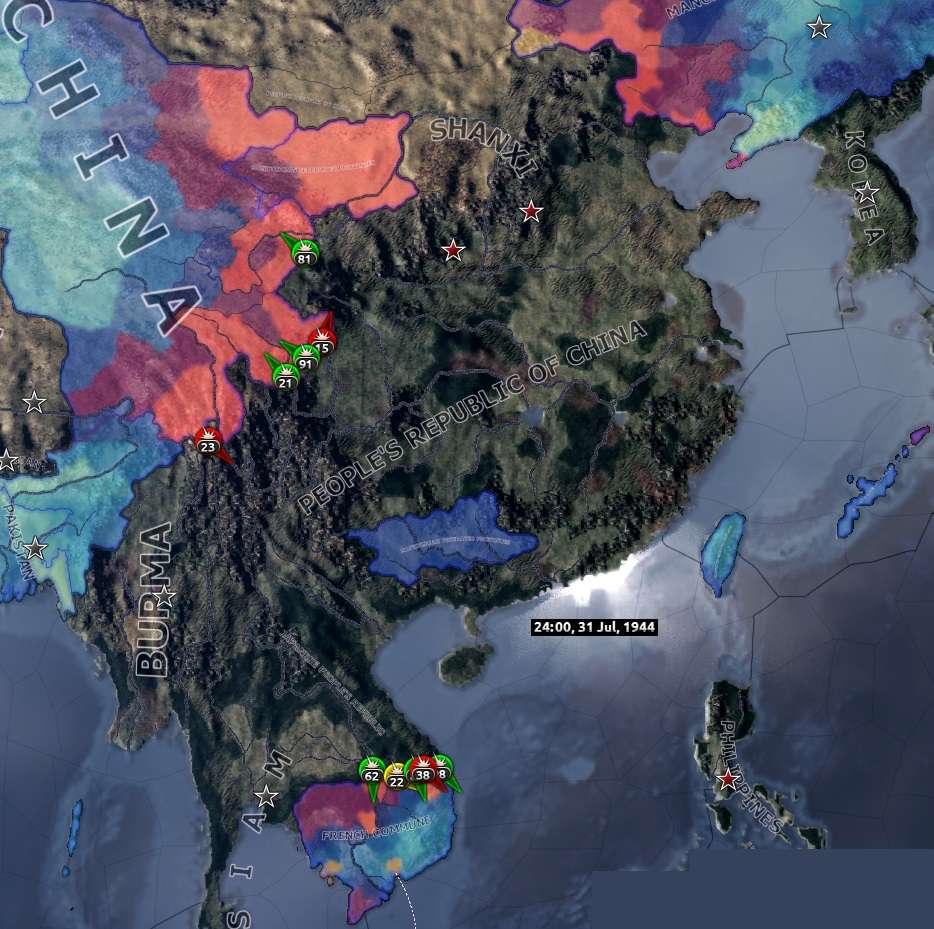

Indochina

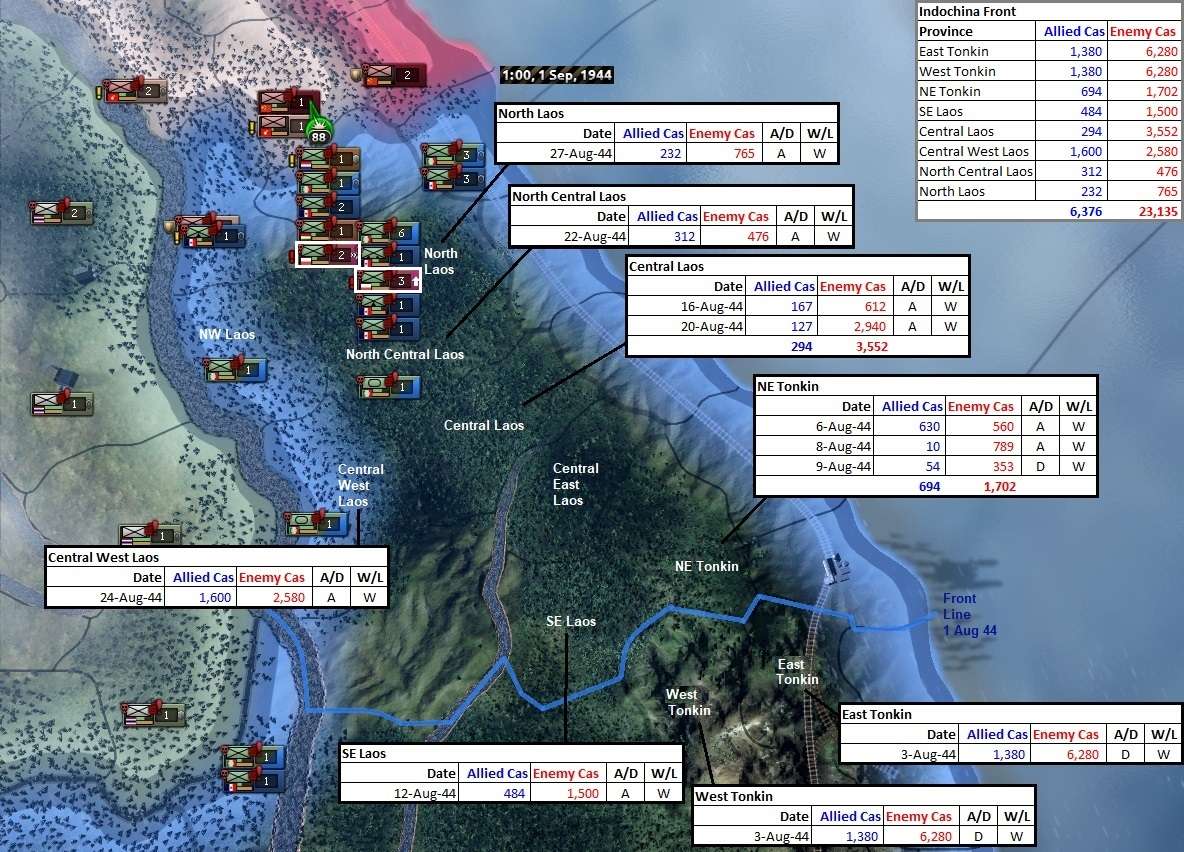

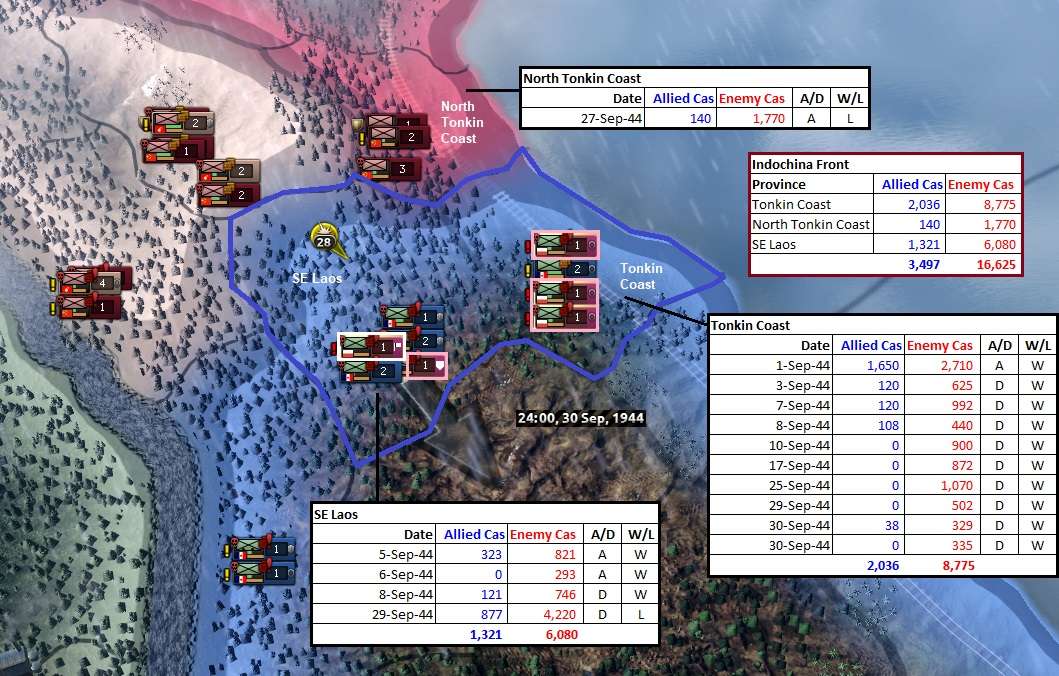

Regular combat had been going on across the narrow, largely deadlocked line in Indochina over the opening week of the month. But on the 7th, a Franco-Dutch attack saw the Dutch troops manage to take a strip of the Tonkin coast from the MAB. They had tried to strike north again but had also been counter-attacked, while the French followed their comrades north to reinforce the breakthrough.

A day later, the Dutch exploitation attack had been defeated, but the French had arrived to help hold the breakthrough. To the west in central Laos, the attack by French mountain troops had driven one MAB division back and now looked like it might also succeed.

By the 12th, one of the replenished Polish divisions from the south (26 DP) had joined the French (the Dutch having gone into reserve to recover by then) in Tonkin and were reinforcing a renewed attack on central Laos to their west, where only one weakened PLA division now remained.

After the MAB reinforced, the tired 15 DP had been added to the attack which had started to bog down, while the fresh 26 DP had yet to reinforce. This combination proved enough to tilt the balance, with victory won that evening. Both the Polish divisions held in place, one of them too worn out to be risked, the other to defend the Tonkin coast against the inevitable MAB counter-attack.

The French did take central Laos but by 16 February had been counter-attacked by five MAB divisions and would be unable to hold the brief gain.

The next day, a force of Italian subs reinforced by Australian light cruisers and destroyers was nearing the end of an engagement where a Philippines troop convoy with a US light cruiser and destroyer escort had been attacked in the South China Sea.

The Australians had lost a destroyer, the Philippines two transports and a US destroyer heavily damaged.

On 18 February, a second refreshed Polish division had reinforced Tonkin, which was just as well: the other French division there had slipped into central Laos before the MAB could occupy it, though were now under heavy pressure to hold it. But the Poles had held off against a larger than average MAB assault by 2000hr that evening (272 Polish and 3,200 MAB casualties).

As the month finished, central Laos had been lost again with four of the five Polish divisions in the sector well supplied and organised, the other (15 DP) on its way back to resupply and reorganise. And one province taken and held during the month.

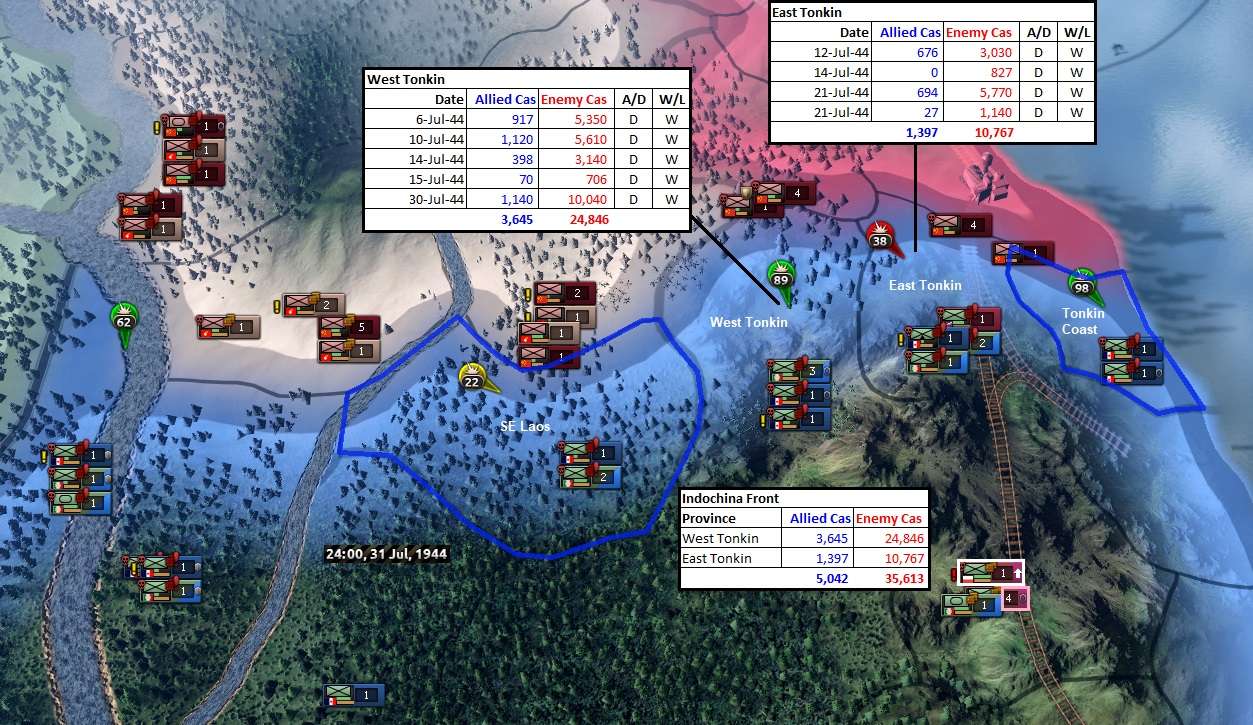

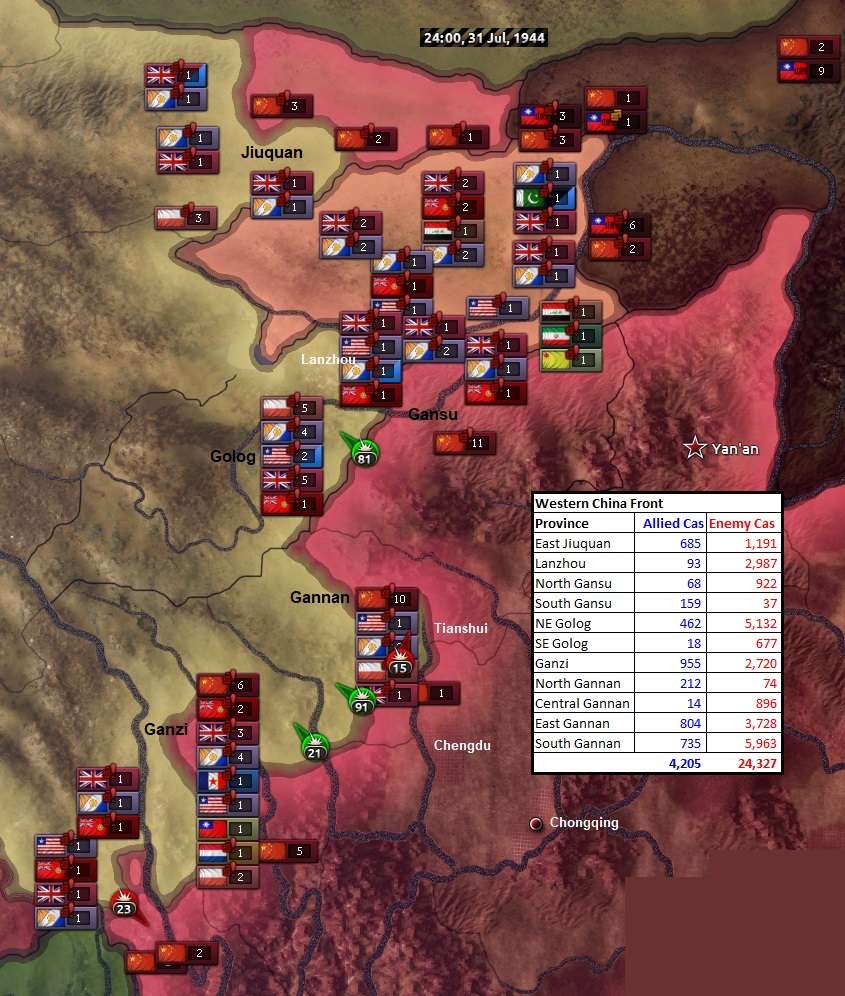

China

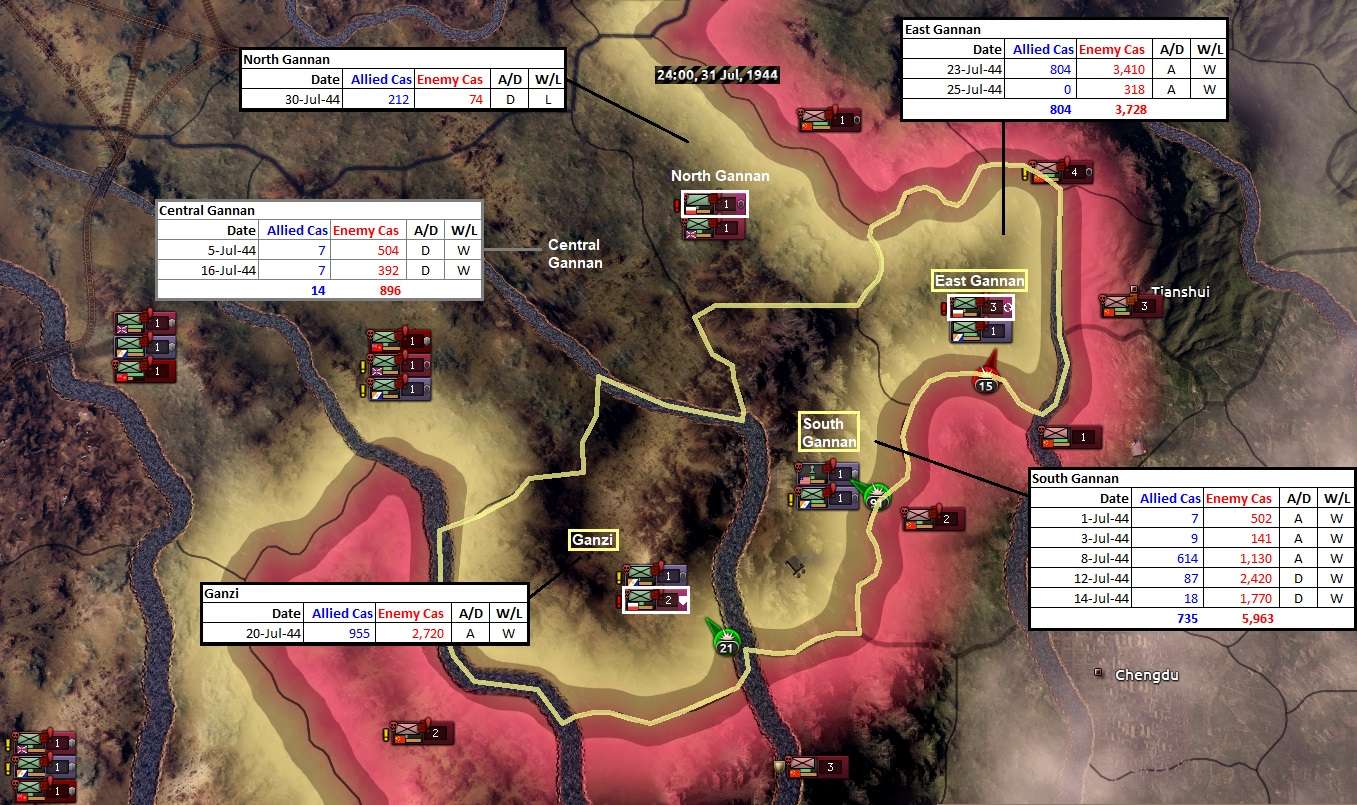

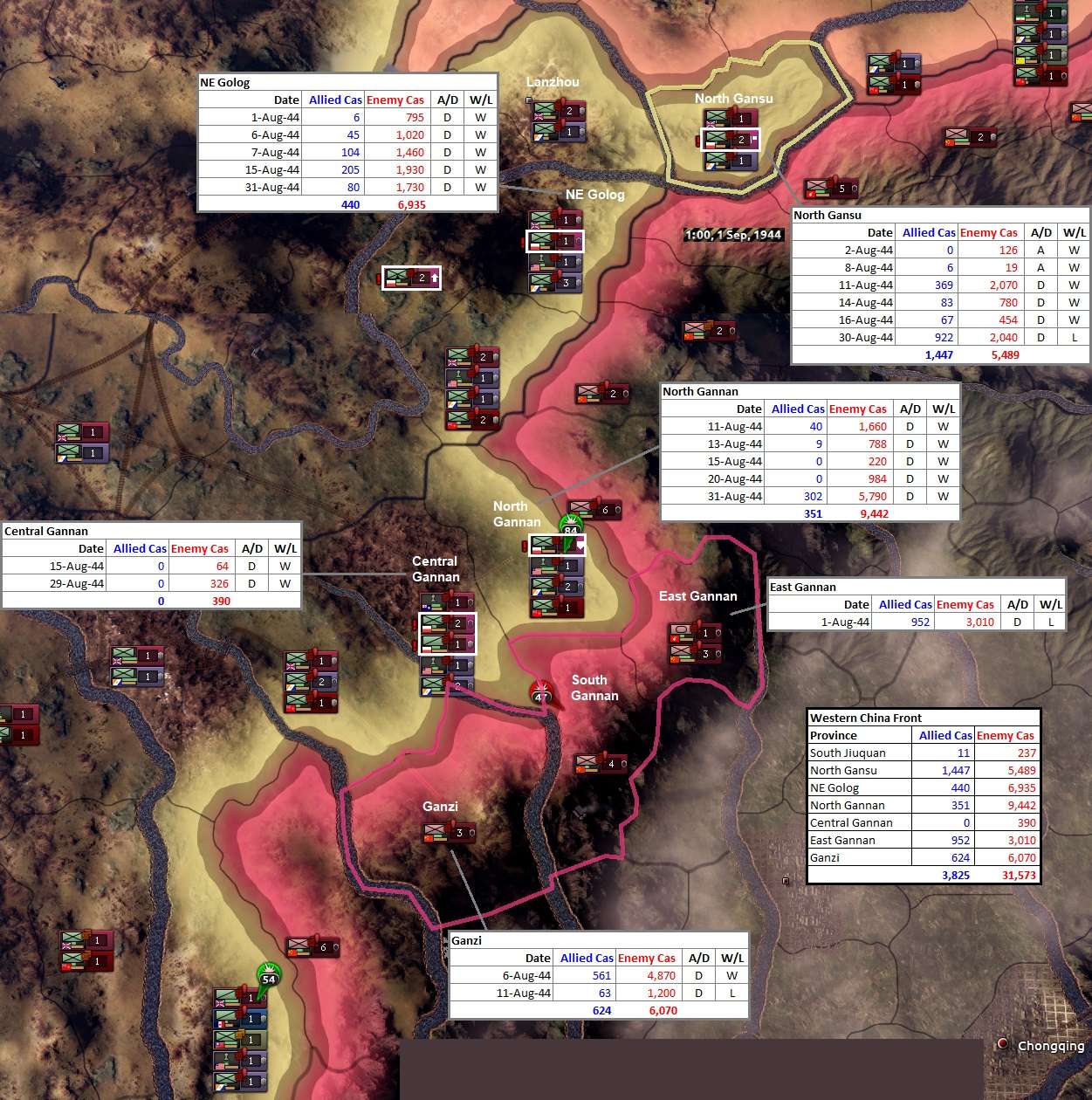

At the start of February, the often-interrupted construction of the new Polish-funded supply hub in Ganzi was 53% complete. It had become the focal point of the Polish defensive effort in the central sector in Western China, but getting troops there took a lot of time in the rough terrain and nasty winter weather.

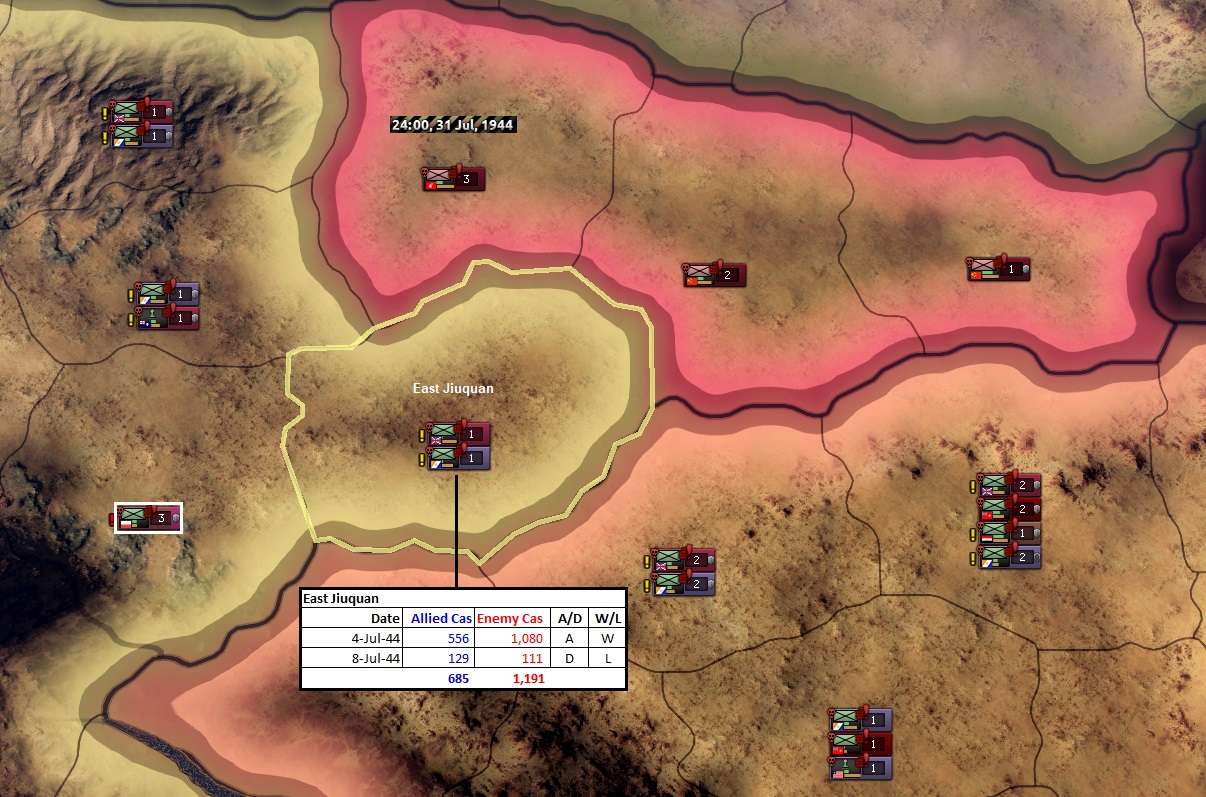

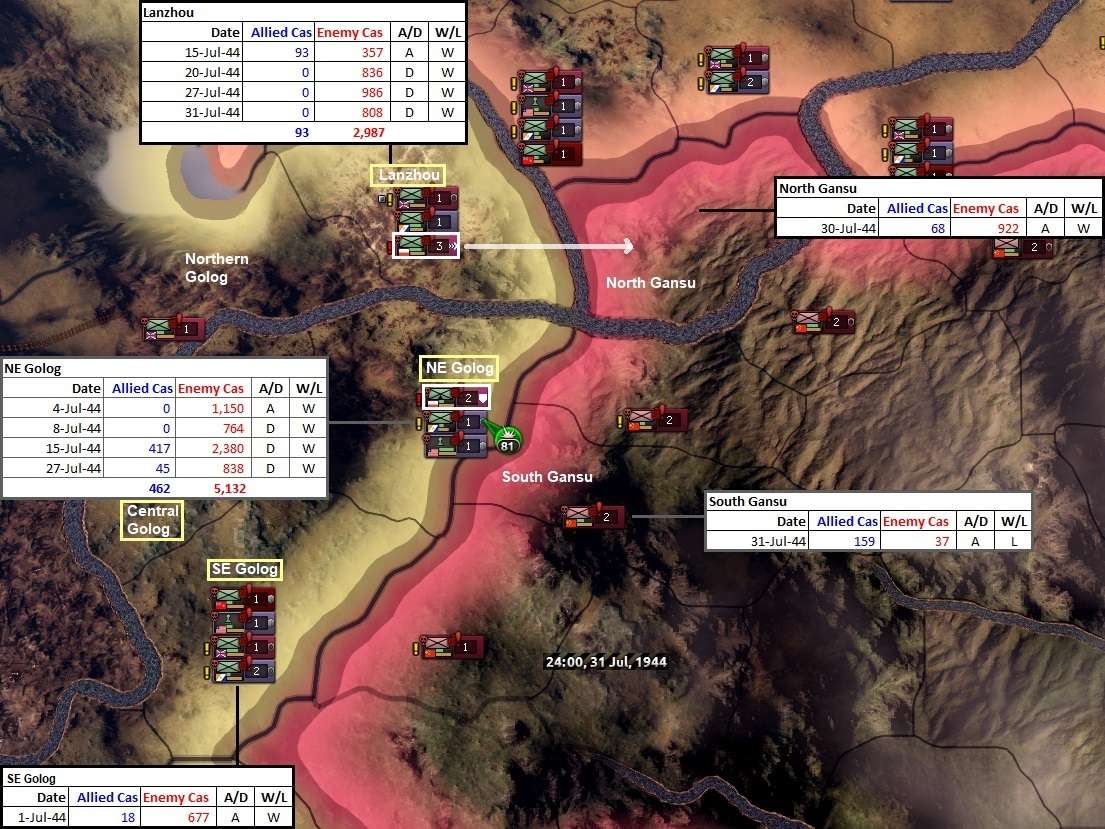

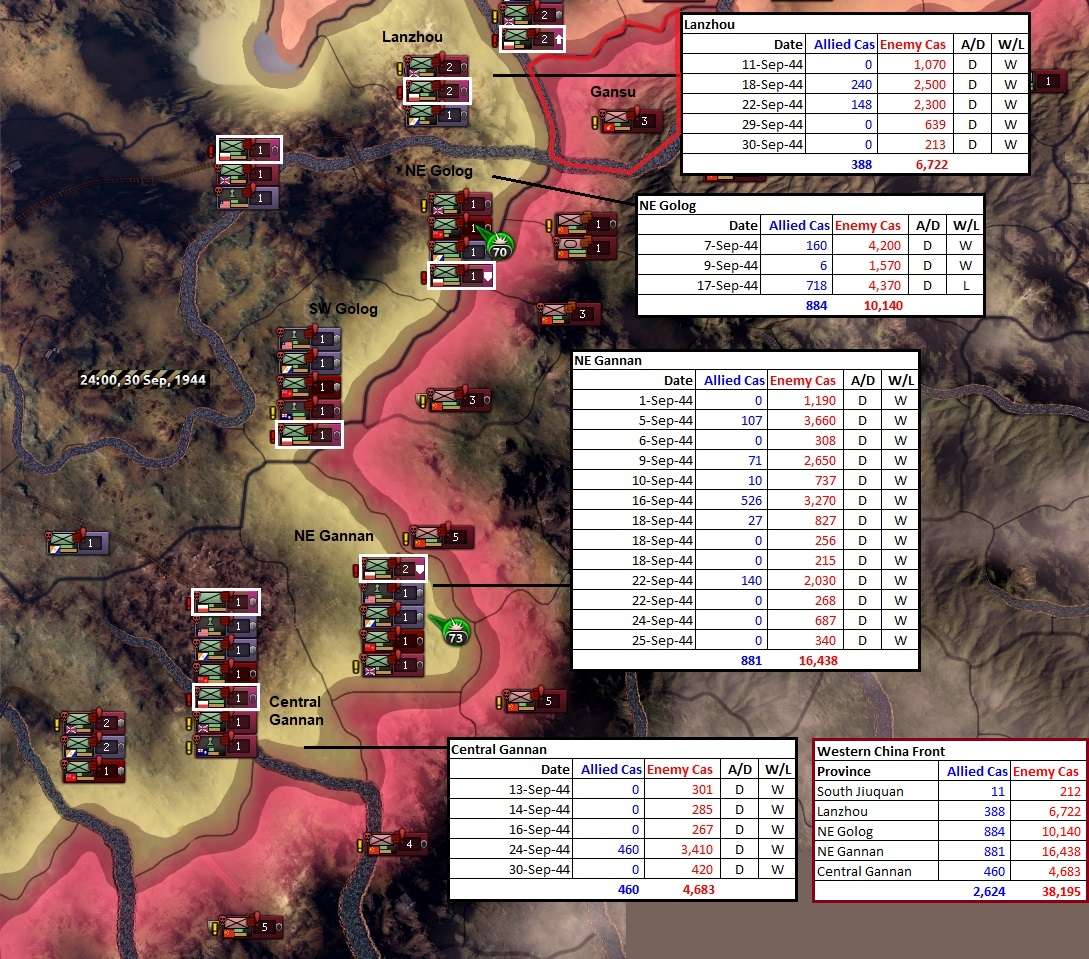

By the afternoon of 1 February, the Allies remained in retreat from Lanzhou (including three Polish divisions) while to its south, in north-east Golog, eight PLA divisions were attacking four Allied divisions, who were looking in a perilous position

[20%, red]. And the PLA was attacking along most of the front to the south of that as well, though not as successfully.

A day later, the situation in north-east Golog had worsened and two provinces to the south, north-east Gannan was now also set to fall, with all three provinces west from there to Ganzi also under attack.

By 3 February, the battle in Ganzi, where 5 and 7 DPs were dug in, turned marginally in the PLA’s favour, while the six exhausted Allied divisions defending north-east Gannan were being assailed by a total of eight PLA divisions. The PLA also pressed forward in the far south of the front: it seemed the whole Allied position from Lanzhou to Burma was in danger of folding.

At this key juncture, Mao decided to declare war on neutral Korea, led by the nominally democratic Syngman Rhee, though the Fascist NDPC was by far the largest single party. They had no direct land border with the MAB, a small army and industrial base, with no navy or air force. Korea was soon drawn into the wider Allied network.

Lanzhou had been occupied by the PLA by midday on the 5th, but the desperate fight for north-east Golog had reached parity again, just as the Allied defence had looked like breaking the day before. The battle for north-east Gannan had been lost, but the Poles had turned the momentum around and were now inching ahead in the crucial defence of Ganzi. In the south, the Allies had also rallied and were now holding their ground.

As mentioned above, the fight for north-east Gannan had been lost back on 4 February. By the start of the 6th, north-east Golog was now holding more strongly, though Ganzi and the provinces of Gannan to its east remained under PLA attack.

The next day, the UK decided it was time for the monthly border clash in Manchuria. It was at least diverting a lot of PLA divisions! Once again, a truce would be called after two days, though this took some time to filter through to all the troops engaged.

It was decided to put the northern Polish reserve that had previously been engaged in the Jiuquan campaign onto trains and ship them south into reserve for this region instead, given the multiple threats. Later that day, the KBK had recovered sufficiently to be ordered back into the line in Ganzi, to shore up the defence there, where heavy fighting continued.

Half-way through the latest Manchurian border clash, the MAB offensive in the north-east (using over 60 mainly PLA divisions) was winning most of its battles against a substantially smaller Allied defensive line.

It was a similar story in the western Manchurian enclave, except for the PLA attack in the north, from Jiuquan. But in the central sector, the Allied defence was gaining strength again.

The latest hard-fought defence of Ganzi was won at 0900hr on 8 February, but a day later a new PLA attack was in progress, though it too was being held off. The PLA had just occupied north-east Gannan.

Later that morning, north-east Golog (where a Polish division was still aiding the defence) was still fighting off attacks from the north and east, even as the Allies launched a promising spoiling attack on Lanzhou. The following day, another Polish victory was won in Ganzi (Poland no casualties, PLA 1,210 killed) allowing the brief recommencement of construction work on the supply hub.

Commentators on the war had speculated about the depth of PRC manpower reserves, given the heavy casualties they regularly absorbed in their mass attacks. An Allied intelligence estimate provided the sobering news that they had around 63

million in the reserve pool in mid-February 1945. The high casualties may contribute to the decrease of experience in hard-hit formations, but they were not going to run out of replacements in a hurry!

It was not until the morning of 14 February that the epic defence of north-east Golog ended, with the PLA losing almost 9,000 men in the attempt. While this was a big victory, the knowledge that they had another 60+ million men to throw into the breach somewhat dampened Allied enthusiasm about this win. It appeared PRC industrial strength was the main constraint for them rather than their manpower stocks.

By that afternoon, the whole Western Chinese front was quiet, with no battles in progress. The latest Communist offensive had been largely weathered.

While no more large battles involving Polish troops occurred for the rest of the month, the PLA had pressed on central Gannan, having just occupied it in the face of an Allied counter-attack, while south-east Gannan had only one division left to defend it, though it was holding for now.

The lull in fighting in Ganzi had allowed the supply hub to reach 66% completion by the end of the month, with an estimated end date pushed back to 19 April. And the defence had been reinforced by two more Polish infantry divisions, the KBK and one division each of South African and Canadian troops.

Overall, the situation in mainland Asia had only changed marginally during the month.

Domestic and Political Matters

A new light armoured division deployed for service near Lwów with the reserve 5th Army on 4 February. The same day a large new rail upgrade program was queued for construction for south-east Poland, to where the largest concentration of Polish and Soviet troops was massed on the border.

A new infantry division (103 DP) deployed to 5th near Rowne on the 17th with the increased training speed saw infantry equipment fall into a small deficit, with South Africa and Manchuria offering surplus stocks for Polish use a few days later. By the end of the month, the first shipments of foreign support equipment had arrived, with the infantry gear due in a little over three weeks.

In peaceful Europe, Polish political efforts in Germany (where the change was negligible from last time), Romania and Belarus were also reviewed.

Of interest, despite all their commitments (and previous losses) in America and Asia, Germany still fielded almost 100 divisions in and around the Fatherland. Poland had 77, the Czechs 24 and Hungary 14 in central Europe. Further south, Yugoslavia had 57 divisions at home.

There had been no new research advances made during February, but new decryption technology (1942 level III) and AA guns (1940 level II) would be introduced in mid-March and the 1944-model PZL.63 Dzik TAC bomber towards the end of March.

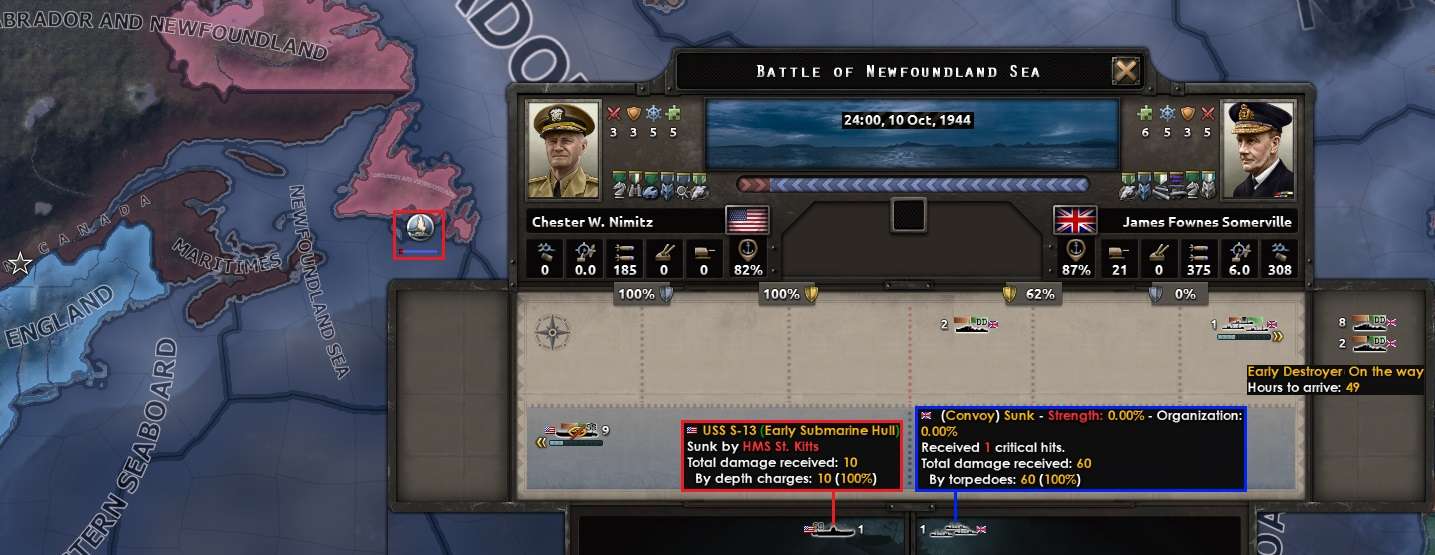

At sea, seven Japanese convoys had been sunk for the loss of 15 Allied transports (mainly Lithuanian and Korean) during February. The US had lost 26 transports for the loss of three Allied (French and Yugoslavian) subs, the one Australian destroyer and seven Allied transports.

] Nevertheless, he served as an advisor to the command of the Polish southern front.

] Nevertheless, he served as an advisor to the command of the Polish southern front.